The Enterprise Canvas, Part 1: Context and Value

After that suitably silly start, it’s time to be sensible and serious. Sort-of, anyway. 🙂

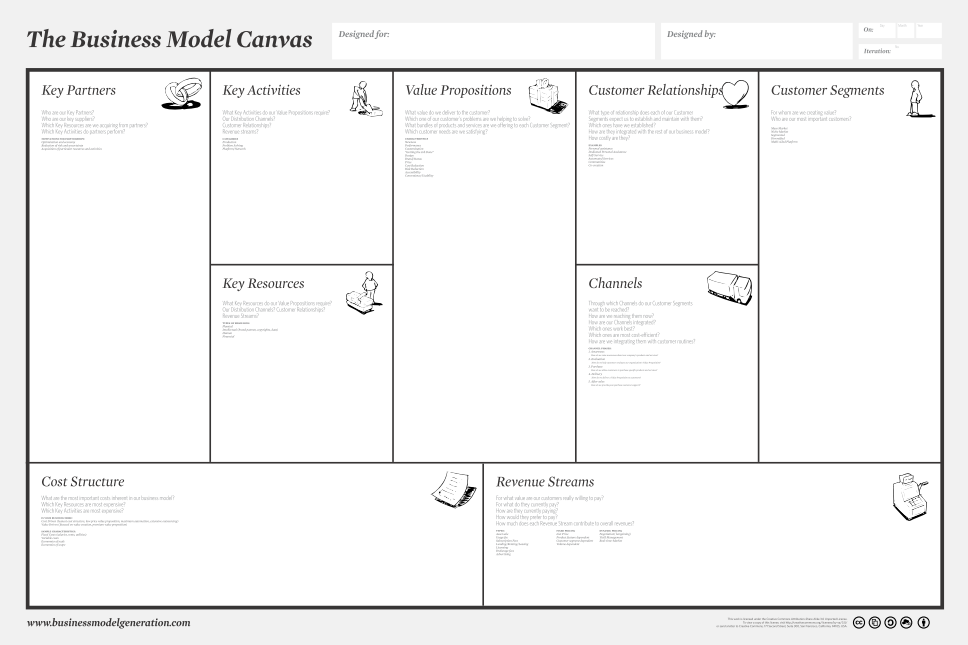

The real story is this: When I first saw Alex Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas, back some nine months or so ago, I was immediately struck by its elegant simplicity:

In effect, it shows the supply-chain for a business-model, centred around the core value-proposition, all cross-linked to revenue-sources and cost-structure. In a word, it’s brilliant. (I’m delighted to say that the book in which the Canvas was introduced, Business Model Generation, is at last coming back into print – published by Wiley – sometime next week. If you don’t already have a copy, get it! – or at least download the generous 72-page sample from the book’s website.)

The trade-off for that simplicity is that it only describes the business-model itself – not how the business-model is implemented, or where it sits within the overall enterprise. (In its present version it’s also only suitable for for-profit organisations, not government or NGOs or the like, but that limitation is already being addressed by Osterwalder and others.) So whilst it’s excellent as a tool for business-architecture, it doesn’t really cover enough scope for enterprise-architecture – either the usual IT-centric ‘enterprise’-architecture or a true whole-of-enterprise architecture. Which is something we really need in EA. Which is frustrating. Oh well.

Most readers of this blog would know that I’ve done a lot of work over the past few years on models and methodologies for whole-of-enterprise architectures, yet I’d have to admit that none of them as yet have really had the immediacy of the Canvas. Most of those models, I’d also have to admit, have been too abstract to make much sense as yet to most everyday architects – especially as most so-called ‘enterprise’-architectures are still centred entirely around IT, with a much narrower scope than we would need here.

Yet it struck me that there might be a way to link all those models together into a single structure that could cover the whole of the scope, from enterprise vision right to way down to the fine-detail of actual operations. The core of this came back to two themes that I’ve worked on for quite a while:

- the enterprise in scope for an enterprise-architecture is larger than the organisation – it needs to include the partners, suppliers, customers, prospects, market and overall ‘ecosystem’ as well as the organisation itself

- everything in the enterprise can be described in terms of services that support the aims of the enterprise – with the organisation itself as a supplier of services to the overall enterprise

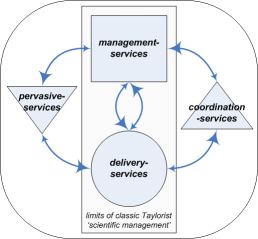

Following on from a more service-oriented view of Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model, we can identify four distinct categories of services:

- delivery-services – the ‘profit-centre’ services that contribute directly to the organisation’s ‘value-proposition’

- management-services that direct what the delivery-services should – the classic vertically-oriented ‘management hierarchy’ and suchlike

- coordination-services that link horizontally across the silos to allow the supply-chains and the like to flow smoothly through the organisation

- pervasive-services that provide various forms of whole-of-system support – finance, HR, infrastructure – and that monitor and maintain quality throughout the organisation

Crucially, classic Taylorism only acknowledges the first two types of services – one of the core reasons why it is so problematic in practice:

All services actually have the same structure, because all of them deliver a service: whatever way we might label or categorise them, in the end every service is a ‘delivery-service’. In effect, all that changes in each case is the value-proposition, and the content that the service delivers: the relationships within and between services remain much the same. This suggests that a service-oriented approach to enterprise-modelling might well give us a conceptual structure that’s as simple as the Business Model Canvas, yet can cover the whole enterprise scope at any level of abstraction.

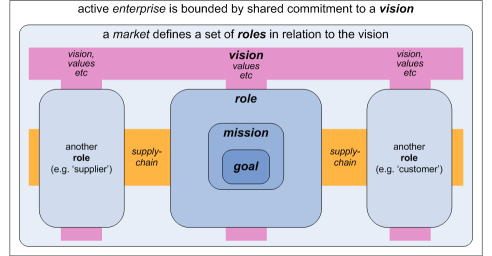

Next is the core distinction between enterprise and organisation. An organisation is also an enterprise, of course, but the two terms are not synonymous: following the definitions in FEAF, an organisation is primarily about legal and similar ‘truth‘-type boundaries of roles, rules and responsibilities, whereas an enterprise is bounded more by values, by agreements and commitments:

An enterprise includes interdependent resources – people, organisations and technology – who must coordinate their functions and share information in support of a common mission or set of related missions. … [I]t must be understood the enterprise may transcend established organisational boundaries – e.g. trade, grant management, financial management, logistics.

The actual core of an enterprise is its vision. Crucially, a functional vision for an enterprise is not a crude piece of self-aggrandising puffery set out as a marketing-pitch – which is what is usually purported to be a ‘vision’ – but is a much simpler phrase or ‘mantra’ that summarises that enterprise’s ‘reason to be’. Good examples of valid visions include the Open Group‘s vision of ‘boundaryless information flow‘, or the vision for the TED conferences, ‘ideas worth spreading‘. The key point here is that the vision is a stable, permanent, shared reference-point for all players in the enterprise – including the organisation for whom we’re building an enterprise-architecture. We can summarise this in terms of the structure ‘vision, role, mission, goal‘:

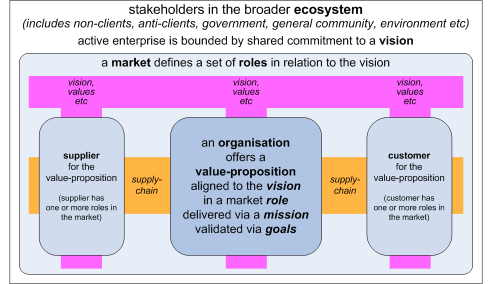

The enterprise vision and values are shared by all players, which in turn is the reason why they are players in that specific enterprise. And each of those players presents some kind of ‘value proposition’ that aligns with the vision and that then links with other players in the enterprise, “in support of a common mission or set of related missions”.

We could explore further this question of ‘what is an enterprise‘, but the key point here is that the vision and values in effect traverse vertically through each player – each organisation – whereas the supply-chain or supply-web provides a kind of horizontal link between them. Each player thus exists at an intersection in a ‘value-web’, a point where organisation brings the vision and values of the enterprise in touch with respective roles of the supply-chain. Every organisation provides a service within its chosen enterprise:

Each organisation can be subdivided into sub-organisations, and sub-sub-organisations, and so on, almost ad-infinitum; and each of these ‘units’ provides a service that delivers value to the overall enterprise. Each service – organisation, sub-organisation, sub-sub-organisation, whatever – has its own emphases on value:

- value-proposition: what the organisation commits to be responsible for (what value it will add to the enterprise) [aligns with quality, with the pervasive-services]

- value-creation: how, where and by what means the organisation will add value to the enterprise [aligns with action, with the coordination-services]

- value-management: how the organisation will ensure that it can, has and will continue to add value to the enterprise [aligns with information, with the management-services]

In a service-oriented architecture, everything is a service – so we’ll see these three value-themes recur in every part and aspect of the organisation and enterprise. If so, it’s clear that we have the beginning of an Enterprise Canvas there – a model that we can use in a consistent way to model anything in the enterprise. Yet that describes only the ‘value’-axis of the value-web: we need to explore the supply-chain axis as well. That’s what we’ll look at in the next part of this series.

Vision and Values (and Beliefs) are many times overlooked or construed as a mission statement. The vision helps one to select what to do and how to do it. It defines the somewhat liquid boundaries of the enterprise. Simon Sinek describes this http://www.startwithwhy.com/ . Those that fail to address and reevaluate the vision will not be as successful as those who have a clear vision.

Pat – agreed. A couple of fairly crucial points, though. The vision for the enterprise has a wider scope (and probably more abstract scope) than the organisation for which we’re creating an architecture: so the ‘vision’ isn’t the usual organisation-centric marketing puff, but something more descriptive, more engaging, that encompasses all players in the extended-enterprise. The other point is that, in order to succeed in its task, the enterprise-vision statement or phrase has a very specific structure: more on that in the later post ‘A structure for enterprise vision’.