Context-space mapping with Enterprise Canvas, Part 2: Business context

In the previous post in this series we did a quick review of context-space mapping and the Enterprise Canvas, and set out this into practice with a real-world example that, for me, is very close to home: rethinking my own enterprise-architecture consultancy business.

We started at the top layer, aiming to identify the core ‘enterprise’ within which I work. From exploring my own professional history, it became clear that the main focus of my work is about enterprises themselves, of any size, and always with the aim of enhancing enterprise effectiveness. From that, we ended up with an initial enterprise-descriptor – or ‘vision’ – of “creating more-effective enterprises”.

Notice, though, what’s happened right here, in that paragraph above. In trying to summarise that initial rather clunky vision-statement – ‘creating more-effective enterprises’ – we’ve accidentally hit upon a better one: ‘enhancing enterprise effectiveness’. It reads better, has a smoother flow to it, a poetry almost. It does describe what I’m passionate about – and finding that passion is central to the success of an enterprise. And ‘enhancing’ is actually a much more accurate term for what I do: I don’t often create enterprises in the sense that, say, an entrepreneur would do, but I do work to enhance their effectiveness. So note that this process is typical of what happens in context-space mapping: for example, we arrive at a ‘solution’ – in this case, the initial ‘vision’-descriptor – which itself quietly dropped us back into the ‘sensemaking’ space. So the trick here is to notice what’s happening, notice these little serendipitous events – and learning how to do that is a real skill in itself. To quote one of my favourite books, William Beveridge’s The Art of Scientific Investigation:

If these discoveries were made by chance or accident alone, as many discoveries of this type would be made by any inexperienced scientist starting to dabble in research as by Bernard or Pasteur. The truth of the matter lies in Pasteur’s famous saying, “In the field of observation, chance favours only the prepared mind.” It is the interpretation of the chance event which counts. The role of chance is merely to provide the opportunity and the scientist has to recognise it and grasp it.

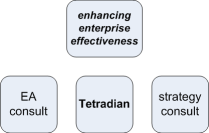

Anyway, that’s what we now have as the ‘row-0’ or ‘Enterprise’ layer for the Enterprise Canvas model of my own enterprise:

Now what? Very pretty and all that, but what do we do with this?

At this point we need to do brief reprise on layering and the Enterprise Canvas. Each entity described in an Enterprise Canvas model is considered to be in just one of seven distinct layers of abstraction, summarised as follows:

- row-0, ‘Enterprise‘: consists of a single entity summarising the overall enterprise, its vision and core-values

- row-1, ‘Scope‘: consists of lists of core entities, such as key assets, key functions, capabilities and services, key events, key players in the enterprise, etc

- row-2, ‘Business-model‘: describes roles and relationships between the key entities in scope

- row-3, ‘System-model‘ (aka ‘Logical model’): includes attributes and events etc to describe more detail about generic ‘families’ of options and ‘platform-independent’ solutions

- row-4, ‘Design-model‘ (aka ‘Physical model’): specifies ‘platform-dependent’ implementation-details, such as specific methodologies, technologies etc

- row-5, ‘Action-plan‘ (aka ‘Operations-model’): specifies individual context-specific instances for final work-plans, such as work-rosters, individual system-configurations etc

- row-6, ‘Action-record‘: detailed records of actual events, actual configurations etc at a specified (past) point in time

(The numbering starts at 0 rather than 1 for compatibility with the well-known Zachman framework, with which layers 1-5 here match almost exactly. Row-0 is unchanging – or should be, because if it does change, it ceases to be the same enterprise. Rows 1-5 represent various abstractions or concretisations of a potentially-alterable plan for the future; row-6 represents the unchangeable past.)

Three points to note about where we’ve gotten to so far.

One is a reminder that although I’ve chosen this as the definition for ‘my’ enterprise, it’s more accurate to say that it chose me: looking at my history and my natural focus and the like, this is the enterprise that I am actually working in, whatever I might think otherwise. Given that that’s the case, it’s more sensible all round if I become more explicit and intentional about aligning my work with this enterprise. And whether the ‘organisation’ in scope is made up of just one person or many millions, the same principles apply.

Next, this enterprise-definition is unchanging: it’s the same for to-be, as-is or as-was. (If it isn’t the same in each case, it’s not an enterprise-definition in the sense that we need here.) As in the ISO-9000 standard for quality-systems, this ‘vision’ provides a permanent anchor for everything that is done in the enterprise. When you work in a business-context that changes on a moment-by-moment basis, it can be very useful to have something that you know will not change whilst you’re working on it…

And note that there’s been no reference yet to the market, to money, or to the organisation itself. That’s intentional – and needs to be that way, too. (As you’ll see later, money doesn’t even rate a mention until we get to ‘System-model’, another three layers further down.) The point here is that the enterprise just is: it’s just an idea, an emotive idea. But until we have that idea firmly in place, and the intermediate layers properly in place too, everything else is at risk of becoming unstable, falling apart without warning – as we can see happening all too often in many large organisations. Yes, the sensemaking and decision-making will often get a great deal messier further down the layer-stack: but for now, in these rarefied levels, all we need to do is Follow The Process.

Anyway, time to move on, to look at the scope in which our organisation exists.

Identifying the scope

In strategy-development, we typically begin ‘top-down’, working our way down through the layers, in a kind of idealised view of the world, until we hit the real-world constraints coming ‘bottom-up’ -which will usually (and usefully!) force us to start being ‘realistic’. So now that we have our row-0 for the Enterprise Canvas, we’ll continue going top-down for a while – which takes us to row-1, ‘Scope’.

Row-1 is always just a list – nothing more than that. Later on we’ll probably come back to make lists of key-assets, key-functions, key-events and so on, but for now all we’ll need is a list of other players – or types of players – within this enterprise. In other words, who else is likely to be interested in the enterprise of ‘enhancing enterprise effectiveness’?

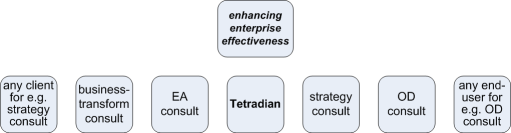

The natural tendency at this point is to start with the as-is, and list my existing customer-groups. I often describe myself as a ‘toolmaker to consultants’, especially in the enterprise-architecture/strategy space, and at first glance it seems that there isn’t much to show:

What’s worse, that market is tiny – probably no more than a few thousand of us worldwide – and, if we jump downward to the Enterprise Canvas row-2 for a moment, most of those that I and my colleagues know are not only our potential customers but potential suppliers and potential competitors as well. Sure, we also do some consultancy, either in setting up enterprise-architecture capabilities or running workshops for executives and in-house consultants – but again, one of the explicit aims there is that we’re training my own future competition each time we do so. And although IT-oriented ‘enterprise’-architecture is quite well-known, true whole-of-enterprise architecture isn’t at all well-known as yet: hence although the need for that kind of work is enormous and all-too-evident, the demand isn’t there – and won’t be, until we’ve created enough awareness of what it is and why it’s so important. The one saving grace here is that the emphasis in this market is always on quality, not quantity: those organisations who do understand what we do are well aware of what it’s worth to them, and are willing to pay for it, so that even a short assignment can fund a fair amount of ‘unbillable’ research and development for the future.

So far, so good – sort of – but in fact this would be setting our sights to far too narrow a scope. Our current market may seem tiny, but by definition the overall enterprise includes anyone with any interest in enhancing enterprise effectiveness. So for a start, it includes almost every consultant and in-house staffer working at a strategic, tactical or operational level to improve just about anything in the organisation: IT, efficiency, innovation, quality, production, skills and competencies, safety, security, risk-management, disaster-recovery – if you can give it a name and it’s anything to do with organisations, it’s likely to be in scope here. What’s even better is that all of these other people are doing work that’s different from ours – so not only may there be potential synergies there for us, but they’re also unlikely ever to be our competitors.

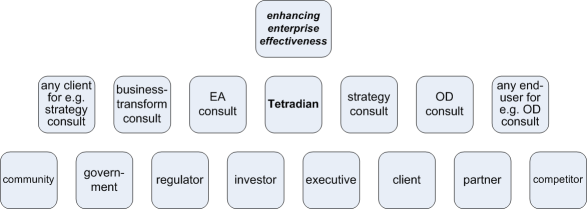

Yet even this is still thinking far too narrow. Who else would be interested in ‘enhancing enterprise effectiveness’, where ‘enterprise’ means anything that the organisation might touch, and ‘effective’ means that the organisation would be more efficient, reliable, elegant, appropriate, integrated, in just about any sense of those words? The short answer is “just about everyone”…

Executives would be very interested. So would investors. Regulators. Government. Business-partners. Business-clients. Standards-bodies. Environmental activists and other pressure-groups. The countries and local communities in which the organisation operates. Even competitors would be interested, if it helps to create a larger or more stable market for everyone. That’s not a small enterprise at all: it’s huge.

So far, this is just a list – a list of players in the enterprise of ‘enhancing enterprise effectiveness’. It doesn’t tell us anything as yet about the relationships between these players – which is what I’ll need to know if I’m to design a viable business-model within the scope of this enormous shared-enterprise. But that’s fine – that’s what we explore in the next layer of the model, which we’ll look at in the next post. For now, though, it’s useful just to bask for a moment in the plain fact that the enterprise – and market – that I’m dealing with is much, much larger than I’d previously believed, providing many more potential opportunities for my business if I make the effort to find them. Food for thought indeed…

Level 1 can be the level that sets our boundaries of what a company (or person) can do (and selected to do today) to satisfy their vision? The potential products, customers, business relationships. This is the Blue Ocean Strategy questions to clarify what is in and out of scope of possibilities (and what should be eliminated from what a company or person is currently doing to get back to it’s core beliefs).

Back to Elevation Burger’s “Ingredients Matter.” http://www.elevationburger.com/EB.php

They choose to make burgers (veggie and beef) and french fries (deep fried in olive oil which is healthier). They could extend their market to include chicken and sweet potato fries. As long as the ingredients are: sustainable, hormone free, etc. because INGREDIENTS MATTER.

Also…what type of companies could be the suppliers. Only those who supply healthy, sustainable ingredients/products. Because … Ingredients Matter.

What type of clients do we want? Our demographic core are people who believe what we believe … Ingredients Matter. (how to reach them and where to reach them would be in a different layer).

What type of employees would be hired … only those that believe that ingredients matter.

Who would invest in Elevation Burger? Those that can visualize the importance (and hopefully believe) that Ingredients Matter.

Once again, Pat, great points and great example – thank you!

That’s exactly the kind of focus we need, and how we would use the vision in practice, after identifying the players and shared-interest within this level.

The only disagreement I would have is where this happens – i.e. at what layer of the overall Canvas. Much of what you’ve described is about ‘our’ relationships with other people/players who would share the same vision (i.e. ‘belong’ in the same enterprise). If we follow the logic of the original Zachman layers of abstraction, this layer (row-1) is just a list: there are no relationships here, other than that of each player to the vision. The relationships between players start to happen (or be described, rather) in the next layer (row-2, ‘Business-Model’): hence much of what you described here – accurate though it is – would more properly belong in the next layer. May I quote this comment there?

In short, gimme a chance, guv’nor, I’s gettin’ there in the writin’, like, honest I is, but I ain’t gotten there yet! 🙂

Always. Just brainstorming with you.

Before you have the “relationship” you need to filter who to keep in and who to keep out. So, who makes the list?

Now…where does this fit?

The filtering happens later (in the next layer) – what we’re doing in this layer is trying to find out who else would be likely to be engaged in or interested in this shared-enterprise that we’ve identified (in the vision and its core-values).

“Who makes the list?” – you do. It’s really important to get that point. Unless you’re a standards-body or the like whose whole aim is to create shared links between people, the purpose of this exercise is almost entirely to support your own organisation – it isn’t really about creating much if anything to share with everyone else. (In fact in many of the more competitive commercial contexts, this part of the enterprise-architecture might be something you’d be very careful to not share with anyone else!)

The crucial point is this: in most cases, we create an architecture about an enterprise, for an organisation. All of this top-layer stuff is about finding something stable for our own organisation. So we identify a vision that describes the enterprise which fits well with the past, present and future of our organisation; we identify other players in that enterprise; we identify relevant relationships, and so on. It’s all about our own strategy, our own strategic anchor. From a marketing perspective, it’s usually a very good idea to be explicit about what we see as the enterprise vision and values, because that creates the near-effortless ‘pull’ that builds relationships that we know will be useful to us (and also dissuade ones that won’t); but the reasoning behind it, and our views of who we see as other players in this enterprise, might well be cards that we hold very close to our chest.

I do get very frustrated with overly-competitive folks who seem terrified of anything that smacks of cooperation – which, yes, at first this may indeed appear to be. But the blunt fact is that business is cooperation: you just need to be clear what that cooperation is, and when and why you need it. And unless this kind of foundation is in place, even the most competitive-seeming strategy will be built on bare soil, and may well blow away at the first breeze of change. ‘Competitive’ strategies used to last for decades: in many industries now, we’re lucky if they manage to last for weeks. That’s why this kind of work is so important now.

So you are saying this layer is still “soft” meaning we have possible participants, not definite participants. No one will be eliminated until the next layer.

Yes, I am. This is just a list of players (or categories of players) in the shared-enterprise implied by the vision – nothing more than that. The only way that someone would be eliminated is if they don’t appear to align with the enterprise-vision (or, to put it the other way round, the only reason for including someone is that they do align in some way with that vision).

There are no relationships here as yet, between us and anyone else: the only relationship is alignment of everyone to the vision. This is important, because when we do look at the possibility of (business-)relationship with someone else, this shared alignment gives a reason for building that relationship in the first place. The respective business-functions and business-capabilities and so on provide the potential to add value to the shared-enterprise; linking the players together in constructive ways is what realises that potential to add value to the enterprise. But again, we’re not looking at that as yet: here we’re solely identifying who else is in the same ecosystem, the same shared-enterprise.

The reason why this is valuable is that, given this, we can change our entire business-model, and even our entire set of business-relationships, and still remain in the same overall enterprise. This has huge impacts (or, more accurately, lack of impacts) on our business-culture, because we can make large surface changes that are only minimally disruptive because the core drivers and values remain unchanged. Trying to force people to change their values within business is always fraught, and fragile at best: this way, relying far more on ‘pull’ than ‘push’, we bypass all of those problems, and yet still have an organisation that can be extremely agile. I hope this will become clear as we move further into this series of articles.

At which point, yes, I’d better get back to writing the next one, hadn’t I? 🙂

Thanks again, anyway.

“This is just a list of players (or categories of players) in the shared-enterprise implied by the vision – nothing more than that. The only way that someone would be eliminated is if they don’t appear to align with the enterprise-vision (or, to put it the other way round, the only reason for including someone is that they do align in some way with that vision).”

So you are filtering at this level…even if it is just the first cut. The relationship is categorizing how they relate to the vision (client, supplier, employee).

I know I’m splitting hairs. I’m trying to clarify that their is a relationship to the enterprise in the selection on who will be part of the enterprise. The lists are categorized into sub lists. Their is NO relationship between the lists…yet. The only relationship to identify is the relationship to the vision.

If you agree with the type of ingredients that matter … you will be on the list and placed in a category (even temporarily). If the process fits the “ingredients matter” then you are on the list. If you sell strawberries with color added, your company or service or product will not be part of the ingredients matter enterprise. If your product is not made of recycled or biodegradable material, you are not part of the ingredients matter enterprise.

I know you’re splitting hairs here, which is good. 🙂 Unfortunately I suspect that you’re still not splitting the right hairs as yet. 🙁 Once again, it feels like you’ve gone too far down into the detail, way too early. You need to bring the abstraction back up at least a notch here, maybe two.

(I think you mentioned once that your default Myers-Briggs profile was something like ENTJ? If so, the ‘J’ approach would cause you trouble here: switch to at least an ENTP, and perhaps even as far over as an INFP, to get a sense of the kind of mindset that’s needed to make this work.)

So yes, there’s a sort-of filtering going on, but it’s still nothing as such to do with the choices of the business for whom we’re building this enterprise-architecture: it’s still above that specific a scope. And again, I’d suggest using the ‘Making Food That Matters’ line here, because it’s closer to an enterprise-vision than ‘Ingredients Matter’ (which is closer to a principle derived from an enterprise-value derived from the vision).

You have the key point here exactly right: “The only relationship to identify is the relationship to the vision”. But what you’ve then done is jumped straight to filtering people in terms of a probable role – e.g. supplier of strawberries. Just hold back on that for a moment – that’s still jumping the gun, that’s what we’ll start to look at in row-2, in more detail in row-3, and again in much more detail in row-4. But here it’s still about alignment, about feelings or commitments more than actions as such. And some of the players in the space will share the same feeling or commitment about ‘Making Food That Matters’ or ‘Ingredients Matter’, without ever being suppliers or customers.

To give one example, the Slow Food movement could be very important player in this extended-enterprise: the burger is the almost archetypal fast-food item, yet Elevation Burger present the interesting paradox of fast-food with a Slow Food approach to the meal itself (e.g. “ingredients matter”). From there, that also links across to much more of the Slow-style mindset, such as the emphasis on ambience, which could bring the Slow Cities movement (and perhaps the Transition Towns movement) into the enterprise scope. None of these would be suppliers as such, but they could well be very important in strategy-development and marketing.

When we get there.

Which still isn’t yet.

Slow down. 🙂

All we’re doing here is building a feel for the extended-enterprise described/circumscribed by our enterprise-vision, the kinds of people and organisations who would be drawn to that vision, and why they would be drawn to that vision.

It’s all about the ‘why’ – still nothing much else as yet, at this level. Hope that makes more sense?

It’s not my mbti (gee…thanks for telling everyone LOL) … it’s my head thinking about someone starting a new business…it’s my bizarch head helping CEOs who lost their way in the market. I’m using Elevation Burger (one because I LOVE their tag line) because it is something tangible to test the canvas.

I think we are both coming from different perspectives. Movement trends and business building. I think they are both valid tests. I go from organization out. You are going from outside influences in. I think this is very interesting. I don’t think either of us are different from a probable audience to use this canvas. It’s just challenging to make it understandable for both.

Ingredients Matter: for the affect on people, the environment, and supply sources (farms, feed, industries).

OK…going to get coffee now.

Apologies re MBTI – someone in our general group of colleagues put it out in a public Tweet a few days ago, and I mistakenly thought it was you. Not that MBTI groupings matter that much, anyway: as far as I’m concerned, everyone can do every MBTI grouping, because they’re not absolutes, they’re just mindsets from which we can pick and choose as appropriate. All that the MBTI ‘test’ does is help identify the usual default-mindset(s) we would use to tackle something like the MBTI test. 🙂

Re organisation-out versus outside-in, what we’re doing here is actually a mixture of both. For example, I used organisation-out right at the beginning, to go back through my own work-history, so as to help identify my probable extended-enterprise; and I used it again in the earlier part of this work, to identify my current market. The huge danger with organisation-out – especially if we use it as our default – is that in effect it always starts from the as-is and/or as-was, which really puts the blinders on re broader possibilities. If you then couple that with the tendency of organisation-out to become organisation-centric, you have the makings of a strategy for ‘change’ that doesn’t actually allow any change at all. On the other hand, going only outside-in leads not so much to Blue Ocean Strategy as blue-sky thinking – in other words so idealised that it’s no actual use at all. Hence the need for balance.

The whole point of these two layers (row-0 ‘Enterprise’ and row-1 ‘Context’) is that they are larger-scope than the organisation itself. By intent, organisation-centric thinking will not work here: to make it work – in the sense of making sense at all – we’re forced to think wider. It forces us to create a space around the existing organisation, within which change is possible. It forces us to think long-term, to think in the abstract, to think of a scope larger than ourselves. And that’s really important in any architecture.

I’m well aware that that kind of abstract-thinking is very alien to a lot of people, especially the “prove it, here, now” folks (those who default to Myers-Briggs ‘ESTJ’, the most dominant mindset amongst middle-managers) – it’s way outside of the natural comfort-zone for that mindset. But unless we do establish these topmost levels, there’s nothing to anchor the rest of the work below. (You can always flip the layers over, of course, with row-0 as the subsoil foundations.) Once we’ve done this part, we can indeed move on to the more ‘normal’ organisation-out views. But we must do this first: we can’t afford to skip over it, or throw in some meaningless chunk of marketing-drivel as a ‘substitute’ here.

Getting the right balance here, between organisation-out and outside-in, is absolutely crucial for longer-term success and to critical success-factors such as sustainable agility. So the process matters here, the discipline matters – and yes, as we can see, it’s a lot harder than it looks at first glance.

Time to move on to the next stage of the work, anyway.