Notes on architecture versus design

Several people, including Nigel Green, Doug Newdick and Kris Meukens, picked up on my comments about architecture versus design in my earlier post ‘Great conversations on enterprise-architecture‘. Nigel kindly wrote a follow-up post on his Posterous blog, and Kris pointed to an earlier blog-post of his own, whilst Doug also added useful comments to both of those blog-posts. As a result, I really ought to clarify my thinking on this a bit…

To me, there’s no fundamental difference between architecture and design: in essence they’re facets or views or emphases or whatever into what is actually the same overall activity, that we might call ‘design-thinking / design-practice’ or ‘hybrid-thinking / implementation’ or a whole variety of other related terms.

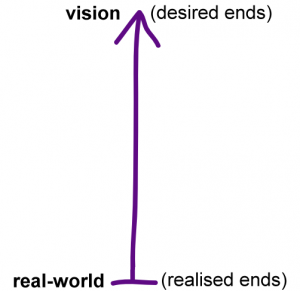

In the simplest possible sense, we could say that ‘architecture-design-whatever’ is the way in which we bridge the gap between what we want to happen, what we’re doing towards achieving what we want to happen, and what we’ve actually done towards achieving that aim. Think of it, perhaps, as a tension between future and past, between desired-ends and realised-ends:

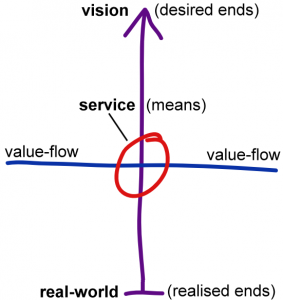

Everything that we might ultimately implement via the architecture/design activity can be viewed as some kind of service at some level of granularity, in that it serves the overall aim that we derive from the ‘infinite future’ of the enterprise-vision. The service delivers value to the enterprise – and towards its aims – by acting on one or more of the value-flows that move around the enterprise:

So architecture/design is primarily about change – about creating a new or modified means to deliver in the real world something that contributes towards the desired ends of the enterprise.

The simplest split between architecture and design, as I said in the previous post, is that architecture focusses more on the ‘why’, whereas design and, especially, implementation, will focus more on the ‘how’. But remember that that’s just a semantic choice: they’re always the same overall activity.

Architecture-design is needed throughout all of that spectrum of change from infinite-future to near-future to now to past. At the very ‘top’ – the infinite-future of the vision – we could say that there is no architecture-work that we could do, because the vision is the architecture, the ultimate ‘why’ for everything in the enterprise. Right down at the ‘bottom’ – the unchangeable past – we could equally say that there’s no design, because there’s nothing to change. Between those two extremes, though, both architecture and design will always occur. Which way we view this activity – in other words, whether we say we’re doing ‘architecture’ or ‘design’ – depends on which way we face at any given time, and at any given point on that spectrum.

For example, let’s take the extended-Zachman that I’ve used in a lot of my books and elsewhere:

In effect, it’s a spectrum of layers of abstraction. And if we take just the standard Zachman layers – rows 1-5 – we should be able to see that what’s called ‘design’ at one layer will look very much like ‘architecture’ for the layer below; and likewise what’s called ‘architecture’ at that layer will be viewed as ‘design’ from the layer above. (What we call ‘implementation’ has much the same ‘downward’ relationship with design – which is what’s always been implied by Zachman’s framework, of course.) In other words, they’re all different views into the same activity, depending on which way we face .

Yet it’s still useful to maintain some kind of distinction between ‘architecture’ and ‘design’, to describe the emphasis within the respective set of activities. (Likewise the distinction between ‘design’ and ‘implementation’ – which to my mind is actually the same distinction at the next layer downward towards realisation.) Some suggestions for such ‘useful distinctions’ would include the following:

Design focusses on the ‘how’; architecture on the ‘why’. We’ve already seen that distinction summarised above – though in some ways we could also describe it as the difference between ‘what’ or ‘with what’ (as design), versus the ‘who’, the human needs and desires in the context (as architecture).

Design focusses on use; architecture on re-use. Or, to put it another way, design focusses on making things concrete, explicit, the implementable specialisation of an abstract idea or pattern; architecture aims to identify the generalisations and abstractions that enable the same design-principles to be applied in different ways. Hence, in turn, Zachman’s distinctions between ‘composites’ (design) versus ‘primitives’ (architecture), or TOGAF’s distinctions between SBBs or ‘Solution Building Blocks’ (design) versus ABBs or ‘Architectural Building Blocks’ (architecture).

Design focusses on content; architecture on context. This in effect combines those two points about ‘how/what’ versus ‘why/who’, and concrete versus abstract.

Design focusses on ‘functional requirements’; architecture on ‘non-functional requirements’. In terms of the practice of design or architecture, this is perhaps the most important distinction of all – and also illustrates why the term ‘non-functional requirement’ is so dangerously misleading. To take the example of a bridge, there is no functional difference between between a plank placed across a stream, and an eight-lane highway across an estuary: they both provide the same function (though you might perhaps describe it as the capability or service) of enabling the passage of some kind of land-based traffic across a body of water. Yet evidently there are huge differences between those two implementations of that same function – and those differences all arise from the ‘non-functional requirements’ that describe the qualitative needs implied by the enterprise-vision.

In the same way, an IT-based service that handles only small volumes of simple traffic with low variability and low criticality will end up looking radically different from one that must handle vast yet highly-variable volumes of complex traffic with high criticality and high levels of guaranteed uptime. The function is essentially the same, yet the ‘non-functional requirements’ dictate a very different architecture for each, and hence very different designs and implementations. (Hence the reason why architecture is essential for agile-design – and yet is so often forgotten because of the over-emphasis on function over everything else…)

The qualitative requirements in effect describe the constraints implied by ‘why’ and ‘who’; architecture adapts those constraints into something that makes sense as a ‘high-level design’; design adapts those constraints into something that is implementable; and so on down through the decision-trees and real-world constraints towards real-world implementation, deployment and use.

That’s my take on this for now, anyway – make of it what you will?

Leave a Reply