Do enterprise-architects design the enterprise?

As the old phrase warns us, “vision without implementation is just hallucination”. That’s why all architects do some form of design, and ideally guide the implementation too. But do enterprise-architects design the enterprise? And if so, how do they do it? Or, for that matter, should they?

These are not trivial questions, as indicated well by these tweets from Chris Potts and Robert Phipps:

- chrisdpotts: @tetradian What comes first in an enterprise, and with that its architecture, is determined by the people whose enterprise it is. // You can choose whether you want be an architect of my enterprise, fair enough, but not what my enterprise is. #entarch

- Robert_Phipps: @chrisdpotts @tetradian this is almost a political resolution to the #entarch question.

The essence of a great sparring-partner is that they come up with great challenges, and these are some of the best. 🙂 Chris is right: the notion that an enterprise-architect designs the enterprise itself seems at first to be a statement of incredible and unforgivable arrogance. And Robert is right, too: by its very nature, all enterprise-architecture work is intensely political – about as political as it gets, really…

And yet enterprise-architects do also do design – in the enterprise. Of the enterprise. About the enterprise.

But only design sort-of. Kinda. Ish. Y’know? That kinda thing? All a bit blurry, subtle… all about implications, edges, options, opportunities…

The real clue is in that comment of Robert’s above: it’s all political. Very. It’s all about people – so it’s not quite the kind of design-thinking that we would use in designing a machine to make toothpaste-tubes. We don’t design enterprises as such: as Chris indicates, they develop from people, as an expression of people and their choices and desires – and the notion that we should, would or even could ‘design’ people or people’s choices is an insult in the extreme. (Not that that’s an unusual insult, unfortunately…)

The enterprise is itself: “the animal spirits” of the entrepreneur and everyday people, as Chris puts it sometimes. That’s the whole point. Yet there is a specific sense in which we do sort-of design about the enterprise. The key resides in what we mean by ‘enterprise’ and ‘organisation’, and the crucial differences between them:

- an enterprise is bounded by vision, values and commitments: it is primarily about ‘Why‘

- an organisation is bounded by rules, roles and responsibilities: it is primarily about ‘How’ and ‘What’ and and ‘Who’ and ‘Where’ and ‘When’- in fact almost everything except ‘Why’

They are not the same: and if we ever make the mistake of thinking that they are the same, we’re in deep trouble. (It’s true that, by definition, the boundaries of an organisation do also coincide with the boundaries of an enterprise – but it’s a special-case, and one of which we should be very wary in enterprise-architectures.) Crucially, the nature of an organisation means that it has no ‘Why’ of its own: to make sense of its existence – to give it a reason to exist – it needs to attach itself to the ‘Why’ of an enterprise that is greater than itself. If it loses that connection, it tends to revert automatically to the dreaded metaphor of ‘organisation-as-machine’ – literally, a machine without a purpose, or at best with a non-purpose such as ‘making money’ that confuses means with ends – that has disastrous consequences for almost everyone involved. One of the key tasks of enterprise-architecture is to identify the enterprise to which the organisation is or needs to be attached, and to help guide the organisation’s responses to and relations with that enterprise. Enterprise-architects do not design the enterprise: they provide decision-support to guide the organisation in its relations with the enterprise. That’s a subtle yet very important distinction.

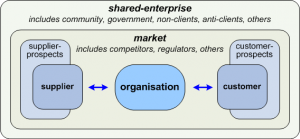

Enterprise-architects develop an architecture about an enterprise, for an organisation. Yet what do we mean by ‘an enterprise’, in this context? The simplest summary is that what we look for is an extended-enterprise or shared-enterprise – defined by some kind of shared and very human drive or intent – that denotes a conceptual and/or emotive space about three steps larger in scope than the organisation itself. The organisation sort-of ‘is’ an enterprise (that special-case, as above) that has a shared-enterprise with its partners – ‘customers’ and ‘suppliers’ – that exists within a broader shared-enterprise – the ‘market’ or its equivalents – that exists within a yet broader shared-enterprise of people who are emotionally or otherwise engaged in that overall aim or intent yet are not actively or directly engaged within that market.

An enterprise simply is: it cannot be ‘designed’ as such. (Nor is it anything that anyone could ‘possess’, or ‘control’ – a mistake still made by too many marketers, managers and MBAs…) Yet each enterprise is also bounded by vision, values and commitments – to which the organisation itself commits by choosing to align itself with that enterprise. The vision, the values, the commitments and even the alignment of the organisation to each of those often starts out as implicit: a key part of the role of the EA is to identify each of those implicit items, bring them into a more explicit space, and hence enable more-explicit and more-considered choices. That’s where the ‘design’ comes in: it’s not design of the enterprise, but about the enterprise, for the organisation in relation to (and relations with) that chosen enterprise.

Enterprises intersect: I’ve shown above a simple case of the organisation in relation to one enterprise, but in reality it’s more like a complex Venn-diagram, overlapping, overlaying, often arguing with each other, too. The organisation’s choice(s) of enterprise to which it chooses to align or belong – with the ‘choice’ often being either implicit and unknown, or mandated by fact of geography or social context – each bring consequences and other choices. For example, the extended-enterprise will hold the organisation accountable to the implied values and commitments of the enterprise, and will react strongly if the organisation fails to deliver on those commitments – which is where many organisations discover to their cost that there is indeed such a thing as ‘corporate social responsibility’, and that it’s not quite as simple as Milton Friedman‘s assertion that the sole social responsibility of business is to increase its profits…

I won’t go into detail on how we deal with those myriad of consequences: as usual, this post is too long already! But essentially that’s it: enterprise-architecture sort-of does and sort-of doesn’t ‘design’ the enterprise. It’s in that ‘sort-of’ where the real interest of the EA role lies. 🙂

Comments, anyone, as usual?

Hello Tom

Thanks for the mentions!

Firstly, the ‘animal spirits’ definition of enterprise is from economics, so please don;t give me the credit for that.

Secondly, I work with people who design enterprises, and designed a few myself. They can be both explicitly and emergently designed.

Your post suggests a reason why executives can struggle to see the value of Enteprise Architecture, and Enterprise Architects. A buildings architect designs buildings; a landscape architect designs landscapes; etc. It is far from arrogant to suggest that enterprise architects design enterprises!

All the best

Chris

Hi Chris

Understood on point 1: I first heard it from you, so I tend to give credit for that reason. 🙂

On your point 2 and the paragraph that follows it, I suspect the problem here is that we may have different definitions of ‘enterprise’. I cannot make any sense of your statement “I .. have designed a few [enterprises] myself” with the definition of ‘enterprise’ that I’ve used throughout my work, as above; though I can make sense of it (but disagree) if I were to use a definition of ‘enterprise’ something like ‘the business of the organisation is the enterprise’.

The problem with the latter notion of ‘enterprise’ is that it gives no reason why anyone else would want to engage with such an ‘enterprise’, and often many reasons why they wouldn’t. Therein lies the very real danger, for executives, of that kind of mis-definition.

I would point you to Mike’s article in his comment above: it echoes exactly the point I’m making.

Hi Tom

I couldn’t agree more with Chris. His view echoes a post of mine a month or so ago http://ebanous.wordpress.com/2011/06/05/who-owns-the-ea/. As architects we are the custodian of the model but we aren’t the custodian of the real thing that is being modeled.

Hi Mike – Reading your post, I might politely suggest that you may have this somewhat the wrong way round? From what you’ve said there, it would seem actually to be more accurate to have said “I couldn’t agree less with Chris”, because your post aligns exactly with what I’ve said in this and other posts, and very much not with Chris’ apparent notion of ‘the enterprise is the business of the organisation’.

The whole point I’m making in this and other posts is that “as architects we are the custodians of the model but we aren’t the custodian of the real thing being modeled”, and that it would be arrogant in the extreme if we were to claim that we were ‘the custodians’ of the real thing – even of Chris’ definition of ‘enterprise’, let alone of the extended-enterprise of vision, values and mutual commitments.

Hi Tom

I have to politely suggest that I’m with Chris on this one. My take on what he was saying is that the architecture you’re designing is the model of the thing not the thing itself. The thing itself is owned by the people doing not the people designing.

I hear and understand your concern about clarity of definition between the organisation and the enterprise but… I’m open to being convinced that this is at the top of Chris’ mind or that of the executives he works with.

I think we are in danger of violently agreeing.