Enterprise Canvas as service-viability checklist

One of the more valuable uses of the Enterprise Canvas is as a checklist to verify completeness and viability of services, in any context within the enterprise.

By ‘completeness’ I mean that we check that the service has all the connections and support and flows that it needs to play its full part in the respective layer of the enterprise value-network.

And ‘viability’ here is in the sense described in the Viable System Model, that the interdependencies that the service needs both to operate in the ‘now’ and to change appropriately over time are all in place and in action.

In a service-oriented architecture and and a service-oriented view of enterprise, everything is or delivers or represents a service. Which means that everything in the enterprise will rely on those interlinks and interdependencies. Which is why a model-type such as Enterprise Canvas, which explicitly sets out to model those interdependencies, could be very useful indeed. 🙂

So here’s an as-brief-as-I-can-make-it how-to introduction on using Enterprise Canvas for this purpose, creating models with the simplified version of the Enterprise Canvas notation.

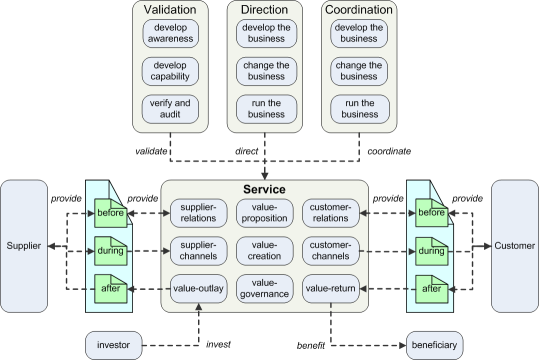

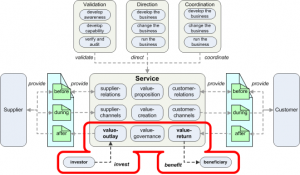

For this we’ll need the (rather large) overview-model of service-relationships, in the simplified notation:

We’ll also need the extended-Zachman map of layers of abstraction:

And the ‘single-row extended-Zachman’ checklist for service-content – the ‘service-content map’:

And to model the flows (Exchange-entities) between services, we’ll also need to check against the market-cycle model, with an emphasis on completions for the different parts of the exchange:

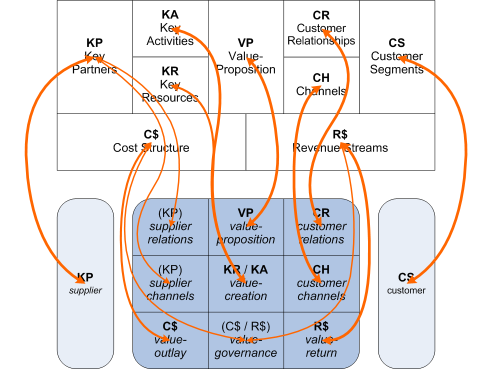

If we want to start from a business-model developed on Business Model Canvas, we’ll need the cross-map from Business Model Canvas to Enterprise:

It’d probably be useful to print out those diagrams – or at least keep them close to hand – for reference as we work our way through this how-to.

So, to get started, pick a service – any service, anywhere in the overall enterprise – that happens to be of interest at present. (If none comes immediately to mind, start with the organisation as a whole, as a ‘service’ in context of its market and the broader shared-enterprise.)

Ideally, this should be modelled using a proper EA toolset. But if a metamodel for the simplified Enterprise Canvas isn’t yet available in the toolset, use an office-diagramming tool such as Visio or Dia – or perhaps just draw the model by hand, on paper or on a whiteboard.

Place a Service-entity in the middle of the model, to represent the chosen ‘service of interest’ – and then see what insights arise as the modelling proceeds…

As-is, to-be and gap-analysis

We can do the modelling in any way we need, for any practical purpose. However, there should always be an explicit business-need or business-question behind every modelling-effort.

We might model the service in an as-is context, describing its current configuration and interdependencies. There often isn’t much point in doing an as-is assessment on its own, though: we’d usually do it to establish a baseline for a roadmap towards some intended future, as the base for a gap-analysis, or perhaps to support a training-programme.

We’ll often do a to-be assessment to support scenarios for change, including business-model innovation via Business Model Canvas and the like. This type of assessment also provides an important endpoint-baseline for gap-analysis.

Often the greatest value of this type of modelling is in gap-analysis: either identifying interdependencies that are misaligned or missing, or – via mismatches between Service-entities and Exchange-entities – identifying misaligned supplier or customer-relationships, opportunities for new supplier- or customer-groups, or risks or opportunities all the way out through the market to the broader shared-enterprise.

The how-to descriptions that follow can be applied to any of these needs.

A note on layers

If you’ve used other IT-oriented architecture-frameworks such as TOGAF or Archimate, you’ll be used to splitting a model into layers in terms of technology versus applications versus business and suchlike. In reality those ‘layers’ are entirely arbitrary, but it’s a practice that can work quite well for domain-specific architectures.

At a true enterprise scope, however, that type of pseudo-layering can be misleading and even dangerous. Hence a reminder here that the only layers explicitly acknowledged in Enterprise Canvas are layers of abstraction, as in the extended-Zachman layering – from most-abstract to most-concrete, from infinite-future to immediate-past. Unlike in IT-architectures, no explicit distinction is drawn between modes of implementation – such as IT versus machine or manual process – because in principle they are all interchangeable. Likewise there’s no mandatory distinction between layers of granularity: the granularity can be shown via composition-relations between Services, but the respective flow-relations and Exchange-entities could legitimately connect to a Service-entity at either level, because it’s literally a matter of detail. The only explicit distinction here is between layers of abstraction.

You can use pseudo-layering if you must, but you’ll have to do so manually, via colour-coding or groups or whatever. Just note that there are very good reasons why it’s not built into the notation.

That point is particularly important here because our aim is to explore direct interdependencies between services. Every relation implies an exchange of some kind, even if the exchange consists only of an acknowledgement that the relationship exists (which we could document in the model as a ‘relational-asset’ within an Exchange-entity). The nature and implied content of the exchange may vary between levels of abstraction, but the exchanges themselves only take place between services at the same level of abstraction. And to understand interdependence, we need to identify the content of those exchanges.

Hence this type of modelling demands a discipline about layering that may take some getting used to, but is extremely valuable in practice:

- in general, flow-relations and Exchange-entities should only connect between Service-entities at the same layer

- changes in layer should be indicated by realisation-relations between Service-entities, which cannot incorporate any Exchange

- where a flow-relation must connect between Service-entities at different layers – such as where the actual service at that layer is unknown – the ‘different-layer’ Service must be indicated explicitly by a dotted-line border

Most modelling for this ‘viability-checklist’ purpose would or should be at a single layer of abstraction. For the supply-chain part of the model, this should be straightforward: any changes in layering should usually be self-evident there. Yet it’s all too easy to scramble the layering when exploring links with guidance-services or with investors and beneficiaries.

For example, if we’re using this checklist to focus on a detail-layer web-service, there’ll be a strong temptation to tick off the Direct::Change guidance-service as ‘IT Strategy’ or the like, and leave it at that. But if we do so, that’d be a real missed-opportunity. ‘IT Strategy’ is abstract, yet there’s real work there that’s done by real people, every bit as real as the web-service that’s our current focus of attention: hence what exactly is the chain of responsibilities and connections – and hence flow-relations and Exchanges between real-world Services – that links between that work and this web-service? There are some valuable insights to be gained there about how the enterprise actually works, and how it maintains its viability: it’s well worth the little bit of extra effort around layer-discipline in order to obtain them.

In short, the discipline that Enterprise Canvas demands around layers of abstraction, can perhaps seem tedious at times: yet in architecture-practice it can be one of the most valuable allies that we have. Don’t skip it!

The service itself

Back to modelling, and to the service in focus.

What is this service? Start by assigning it a name. (If you’re doing this within an EA toolset, provide a brief description as well.)

What layer of abstraction will we use as the base for modelling this service? (Usually this will be either row-2 ‘Business-model’, to describe the overall context, without much if any description of actual content; row-3 ‘System-model’, the implementation-independent ‘logical’ layer, where we start to fill in the details of the content of services and the inter-service exchanges; or row-4 ‘Design-model’, the implementation-specific ‘physical’ layer. Remember that if any specific technology or implementation is mentioned, by definition it’s at row-4 or below.)

Apply a RACI assessment to the service:

- Who is ultimately responsible or accountable for this service?

- Who assists in delivering or running or supporting this service?

- Who needs to be consulted about this service, or any changes to this service?

- Who needs to be informed about the performance of or changes to this service?

What other responsibilities and accountabilities apply in this context?

Nature of service

As a first step in the functional decomposition of the service – what it does, and how, and why – focus attention on the three innermost ‘cells’ of the Enterprise Canvas view of the service.

What value does this service provide – its Value-Proposition, in terms of the aims and needs and values of the broader extended-enterprise? (If cross-mapping from Business Model Canvas, this is a more enterprise-oriented version of that model’s Value-Proposition.) If appropriate, build a trail of linkage up through the layers of abstraction, to connect with the vision and values of the shared-enterprise. To model this, link this service to at at least one other Service-entity in each layer upward to row-1; then link to one or more Value-entities in row-0, and ultimately to the Vision-entity at that top of the abstraction-‘tree’. (We’ll come back to some of this later when we explore this service’s links to other Validate services.)

What does this service do to create and deliver that value – its Value-Creation in terms of that Value-Proposition? (If cross-mapping from Business Model Canvas, this merges the latter’s Key Resources and Key Activities cells.) Use the service-content map (single-row extended-Zachman) to explore and identify the various assets, functions, locations, capabilities, events and decisions that apply within that value-creation. (We’ll come back to some of this later when we explore this service’s links to other Coordinate services.)

What does this service need to govern its service-delivery – its Value-Governance to keep the Value-Creation on-track to the Value-Proposition? (This isn’t really described at all in Business Model Canvas.) How does it do this? Under what business-rules? (We’ll come back to some of this later when we explore this service’s links to other Direct and Validate services.)

Apply a RACI assessment to each of these subsidiary ‘cells’ within the service: who is responsible or accountable, for what, and why?

Service-provision

For the next step we explore what this service provides to others – and who those ‘others’ might be.

We have several different ways to do this. One would be to focus mainly on the service itself, and infer the resultant exchanges with others; another would be to focus on the exchanges; and yet another would be to identify the ‘others’ (often described as ‘clients’ or ‘customers’ or ‘service-consumers’). For this how-to, we’ll start with the exchanges – but note that the other options are just as valid.

In a conventional transaction-oriented supply-chain model, this would explore only the goods or services delivered to others – and those ‘customer-side’ others are always considered to be distinct from anyone on ‘supplier-side’. We can model this in Enterprise Canvas, of course. Here, though, it’s usually wiser to use a more-complete value-network approach, in which the mapping of what happens before and after the main-transactions is every bit as important as the transactions themselves – and in which the supposed distinctions between ‘supplier’ and ‘customer’ will often tend to blur. For our purposes here, we’ll describe ‘customer’ and ‘supplier’ as if separate: but note that in many contexts in the real world, ‘supplier’ and ‘customer’ may well be the same.

What does this service provide to others – the services (or products, as proto-services or proxy for services) consumed by others? Using the ‘Assets’-column of the service-content map as a guide, what forms does this service-provision take? Using a VPEC-T assessment, what values, policies, events, content and trust apply in each service-provision by this service? Model the results of this assessment as one or more Exchange entities, linked via flow-relations to the right-hand (‘outgoing’) side of the Service-entity.

Who or what are the ‘customers’ or ‘consumers’ of these services? (If cross-mapping from Business Model Canvas, these are the various customer-groups in the Customer Segments cell.) For each distinct customer-group, there should usually be a distinct Exchange; if necessary, split the overall exchange-content into further Exchange-entities, each linked to a Service-entity for each respective customer-group.

Review each Exchange in terms of what aspects of the overall exchange and its content take place before, during and after each main-transaction. Use the market-cycle model to map these as follows:

- What reputation, trust, relations and attention need to be in place before each main-transaction? What Customer-Relations subsidiary-services exist within the service to support the interactions that would enable these to be created and maintained? (In Business Model Canvas, this is the content in the ‘Customer Relations’ cell.) In market-cycle terms, what completions are needed to ensure that these are maintained as required, especially over the longer-term?

- What are the core transactions in the service-delivery, and what happens during those transactions? Via what Customer-Channels or other means are the services delivered? (In Business Model Canvas, this is the content in the ‘Channels’ cell.) What protocols are needed to set up each transaction itself? In market-cycle terms, what completions are needed to mark the end of the transaction, and ensure that the transaction itself is closed-off and complete?

- What follow-up interactions need to occur after the main-transaction – such as payment and the like? What Value-Return subsidiary-services exist within the service to support these interactions? (Some parts of this are implied by the content of the ‘Revenue Streams’ cell in Business Model Canvas.) In market-cycle terms, what completions are needed to ensure that everything is complete and all parties are satisfied?

Define subsidiary Exchange-entities for each of these before, during and after flows, and link these via flow-relations to the respective subsidiary-cells of the service.

Optionally, use the service-content map to summarise the assets, activities and other content for each of the subsidiary-services.

Apply a RACI-assessment to each of these ‘customer-side’ subsidiary-services within the service, to identify responsibilities and accountabilities for each aspect of the Exchange-transactions and relations with the respective ‘customer’-service.

Given that the before, during and after interactions may all occur at different times, through different channels and on different time-scales, what mechanisms exist within the service to keep them all in balance, and appropriately linked to the core Value-Proposition, Value-Creation and Value-Governance of the service? Who or what is responsible for enacting and governing each of these internal activities and interactions?

Consuming other services

Next, we explore the ‘incoming’ side of the service – the services provided by and ‘consumed’ from others – and identify who those ‘others’ might be.

This is the symmetric-opposite of service-provision, and hence we should assess and model it in exactly the same way. The ‘others’ in this case are usually described as ‘suppliers’ or ‘partners’.

What does this service consume from others – the services or products provided by others? What forms does this service-provision take? What values, policies, events, content and trust apply in each service-provision to this service? Model the results of this assessment as one or more Exchange entities, linked to the left-hand (‘incoming’) side of the Service-entity.

Who or what are the ‘suppliers’ or ‘partners’ for each of these services? (If cross-mapping from Business Model Canvas, these are the content of the Key Partners cell.) For each distinct supplier-group, there should usually be a distinct Exchange; if necessary, split the overall exchange-content into further Exchange-entities, each linked to a Service-entity for each respective supplier-group.

Review each Exchange in terms of what aspects of the overall exchange and its content take place before, during and after each main-transaction. Use the market-cycle model to map these as follows:

- What reputation, trust, relations and attention need to be in place before each main-transaction? What Supplier-Relations subsidiary-services exist within the service to support these? (This is implied in part in Business Model Canvas by the Key Partners cell cell.) What completions are needed to ensure that these are maintained as required?

- What are the core transactions in the service-delivery, and what happens during those transactions? Via what Supplier-Channels or other means are the services delivered? (Again, this is implied in the Key Partners cell in Business Model Canvas) What protocols are needed to set up each transaction itself? What completions are needed to mark the end of the transaction, and ensure that the transaction itself is closed-off and complete?

- What follow-up interactions need to occur after the main-transaction – such as payment and the like? What Value-Outlay subsidiary-services exist within the service to support these interactions? (Some parts of this are implied by the content of the ‘Cost Structure’ cell in Business Model Canvas.) What completions are needed to ensure that everything is complete and all parties are satisfied?

Define subsidiary Exchange-entities for each of these before, during and after flows, and link these to the respective subsidiary-cells of the service.

Optionally, use the service-content map to summarise the assets, activities and other content for each of the subsidiary-services.

Apply a RACI-assessment to each of these ‘customer-side’ subsidiary-services within the service, to identify responsibilities and accountabilities for each aspect of the Exchange-transactions and relations with the respective ‘customer’-service.

What mechanisms exist within the service to keep all of the before, during and after interactions in balance, and appropriately linked to the core Value-Proposition, Value-Creation and Value-Governance of the service? Who or what is responsible for enacting and governing each of these internal activities and interactions?

Who or what is responsible for the overall balance across the whole of the service? (In principle this is a key part of the role of the Value-Governance subsidiary-services, but may in part be enacted by others: if so, who or what are they, and what mechanisms exist to ensure balance?)

Guidance service-relationships

The concept of ‘guidance-services’ is adapted from Viable System Model. (More accurately, a somewhat-extended version of Viable System Model – see my book The Service-Oriented Enterprise.) These represent the web of service-interdependencies that would ensure the viability of the service – the effectiveness of its operations at run-time, and its adaptability and resilience to change, especially over the longer-term. In line with Viable System Model, they’re described in Enterprise Canvas under three categories:

- direction – services that assist in planning and day-to-day management of this service and its clusters of related services

- coordination – services that assist in run-time coordination with other services, and with planning and coordination of change

- validation – services that help to keep the service on-track with and aligned to the vision and values of the shared-enterprise

These services or functions may be embedded somewhere within the service itself, though more usually enacted by separate business-functions. In a few cases – especially some aspects of validation-services – they may be required by law to be enacted by a completely separate organisation. Yet in whatever form they may be implemented in real-world practice, the point is that they must all exist somewhere, in some form, in an engaged relationship to this specific service. That’s the real concern here.

Note that these most of these guidance-services are implied or described only peripherally – if at all – in conventional transaction-oriented architectures and business-models. Classic Taylorist ‘scientific management’ describes some aspects of the direction-services, but nothing else; Business Model Canvas and classic IT-centric ‘enterprise’-architectures do not describe any of them at all. There is a very significant architectural gap here that is rarely addressed – and needs to be.

For many enterprise-architects, much of this part of modelling with Enterprise Canvas may seem at first to be somewhat alien territory. The reason that it’s important is that unless these interdependencies are properly in place and in action, the service cannot be considered viable. Every ‘missing’, incomplete or inappropriately-supported interrelationship in this part of the Enterprise Canvas checklist represents a real and significant risk to the entire enterprise – risks that must be acknowledged and addressed so as to ensure the viability of the whole.

In short, don’t skip over this – there are very good reasons why these service-interrelationships are included in the Enterprise Canvas checklist!

Guidance – direction

The direction-services represent the usual ‘management’-type functions of the enterprise, seen here in relation to the service that is our current focus of attention.

Note that these ‘management-functions’ are viewed here solely as services in relation to other services, just like everything else. In many organisations, front-line services often seem to be regarded as ‘inferiors’, as ‘servants to the whims of management’, whereas from an architectural perspective it usually needs to be seen as more the other way round, that the real role of management is as a support-service to front-line service-delivery. In Enterprise Canvas, no special priority or importance is accorded to ‘the management’, for the simple reason that doing so doesn’t work: in a true enterprise-scope architecture, everywhere and nowhere is ‘the centre’, always, all at the same time. If you must treat management as ‘special and different’, do so outside of the architecture itself! 🙂

These services can be split into three distinct groups, often referred to as ‘Develop the Business’, ‘Change the Business’ and ‘Run the Business’. (In Viable System Model, these are referred to as system-5, system-4 and system-3 respectively.)

In a classic Taylorist view, ‘Develop’ and ‘Change’ are primarily staff-functions, whereas ‘Run’ is primarily a line-management function. There’s also a timescale-element here: ‘Develop’ tends to have a long time-view, ranging from years or decades, potentially all the way to infinity; ‘Change’ has a medium-term view, from the current quarter out to a few years ahead at most; whilst ‘Run’ is mostly focussed on the day-to-day. Strategy develops out of the intersection between ‘Develop’ and ‘Change’; tactics from the intersection of ‘Change’ and ‘Run’; and operations from the intersection between ‘Run’ and this service.

Most of these services must not and cannot be outsourced to another organisation.

Questions to ask here include:

- Direction::Develop – What support for long-term direction does this service need? What services would ensure that this service is aligned to the overall Vision for the enterprise? By what means are these ‘Develop’ direction-services delivered to this service? Who or what is responsible for providing these services to the organisation in general, and to this service in particular?

- Direction::Change – What support for medium-term strategic direction does this service need? What services would ensure that this service is aligned to the changing context of its market and business-ecosystem? By what means are these ‘Change’ direction-services delivered to this service? Who or what is responsible for providing these services to the organisation in general, and to this service in particular?

- Direction::Run – What support for day-to-day management does this service need? What services would ensure that this service has the resources that it needs to do its work in creating value? What performance-metrics does this service need to provide to those ‘Run’ direction-functions? How are those performance-metrics used in providing management-services to this service? By what means are these ‘Run’ direction-services delivered to this service? Who or what is responsible for these services, and how they apply to this service?

Identify the services and exchanges in each case, typically using the service-content map to assess the content of activities of each service, and VPEC-T analysis or the like to identify the values, policies, events, content and trust-concerns implied in each exchange. Add the results of this assessment to the model as Service-entities and Exchange-entities, linked to the service-in-focus via flow-relations. Use either containment (as in the diagram above) or composition-relations to link each of these Service-entities to the overall Direction Service. Annotate each flow-relation here with a ‘direct’ label, to indicate that the flow delivers direction-services to the service-in-focus.

A reminder here to be careful about layering: see ‘A note on layers’ above.

In essence, ‘Develop the Business’ is an architectural function for the organisation in relation to its shared-enterprise: in a very literal sense, the CEO is the organisation’s ‘Chief Enterprise Architect’. (Enterprise-architects provide decision-support for that role, but not the decision-making: that distinction is extremely important in practice!) The catch is that the CEO needs to do that work – but often doesn’t, and instead hides out in a comfort-zone of ‘Change’ or even ‘Run’, subsuming all the other management-functions into that role. This is a common cause of dysfunctional management and architecturally-inadequate support to the organisation’s overall services: classic examples include contexts where purported ‘shareholder-value’ is assigned absolute priority over everything else,or where “last year plus 10%” is considered to be a real strategy. This type of problem will almost invariably lead to organisational failure over the medium- to longer-term: it is an extremely important architectural risk to the organisation, and to the enterprise as a whole.

In short, if adequate and appropriate direction-support is not available, the service will not be viable.

Guidance – coordination

The coordination-services represent the business-functions that coordinate this service with other services.

These services can be split into three distinct groups, often referred to as ‘Develop the Business’, ‘Change the Business’ and ‘Run the Business’, in parallel with the matching functions in the Direction-services. (In Viable System Model, some aspects of ‘Coordinate::Run‘ are referred to as system-2. That model does not deal with coordination of change as such, hence has no explicit component for Coordinate::Develop or Coordinate::Change.)

In Taylorism these services are usually regarded as part of the ‘management’-functions, but in practice they often need to separate and distinct, not least because in many cases they must somehow bridge between management-hierarchy silos. Significant organisational problems can arise from that one fact…

In practice, Coordinate::Develop relates to coordination of strategy and strategic change, and hence links to both Direct::Develop and Direct::Change; it’s also often associated with portfolio-management and the like. The Coordinate::Change services focus more at the tactical level, and hence link to Direct::Change and Direct::Run; one classic aspect of these service is project-management and the Programme Management Office. In principle, the Coordinate::Run services would bridge between Direct::Run and the actual delivery-services (between system-3 and system-1 respectively, in Viable System Model terms), but in practice this is sometimes regarded – especially by questionably-competent managers – as ‘insubordination’, and hence at the human-coordination level may disappear into a kind of covert ‘shadow network’ via which work is actually coordinated and done. Architects can sometimes run head-on into unexpected political-problems when doing this part of the modelling work: a certain amount of caution may be advisable here!

It’s quite common for some aspects of these services to be outsourced to other organisations: if so, there would be additional coordination-services required to manage and coordinate the outsourcing process itself.

Questions to ask here include:

- Coordinate::Develop – What support for long-term strategic change does this service need? What services would ensure that this service is aligned to the overall enterprise strategy? By what means are these ‘Develop’ coordination-services delivered to this service? Who or what is responsible for providing these services to the organisation in general, and to this service in particular?

- Coordinate::Change – What support for medium-term tactical change does this service need? What services would ensure that this service is aligned to and fully supports the changing context of its market and business-ecosystem? By what means – such as programme- or project-management – are these ‘Change’ coordination-services delivered to this service? Who or what is responsible for providing these services to the organisation in general, and to this service in particular?

- Coordinate::Run – What support does this service need for run-time coordination with other services? What services would ensure that this service has the coordination with others that it needs so as to do its work in creating value? What information-flows, signalling or protocols are needed in this coordination-support? By what means are these ‘Run’ coordination-services delivered to this service? Who or what is responsible for these services, and how they apply to this service?

As before, identify the services and exchanges in each case. Add these to the model as Service-entities and Exchange-entities, linked to the service-in-focus via flow-relations. Use either containment or composition-relations to link each of these Service-entities to the overall Coordination Service. Annotate each flow-relation here with a ‘coordinate’ label, to indicate that the flow delivers coordination-services to the service-in-focus.

Identifying coordination-relationships between services is usually fairly straightforward, although it’s all to easy to fall into layering-mistakes in the modelling process here. (Hence another reminder to be careful here about layering: see ‘A note on layers’ above.) A lot of useful insights can be gained here about the interconnectedness of the enterprise, and its dynamics over time. Note, though, that there are also some important architectural risks (and opportunities) to be identified here: in short, if adequate and appropriate coordination-support is not available, the service will not be viable.

Guidance – validation

The validation-services help to keep everything aligned to the enterprise values – whatever those values may be. Note that there are usually distinct sets of validation-services for each key value of concern in the enterprise. Typical examples of values in this context include quality, probity, security, ethics, health and safety, knowledge-sharing, sustainability, waste-management, efficiency, effectiveness, and also architecture itself.

A crucial point here is that, unlike strategy, management, coordination or change, maintaining these values is a personal responsibility for everyone in the enterprise. There’s often a small core-group tasked with ‘holding the flag’ for the respective value within the organisation, and it’s those people – the knowledge-management, the quality-team, the security-team and so on – who we would often regard as the people who deliver such services. In reality, though, it’s only the support-services around each value that most would deliver: the actual implementation and expression of that value in practice must somehow be embedded and enacted, as activities and checks and the like, within every service in the enterprise.

These support-services for value-alignment be split into three groups: ‘Develop Awareness’ of the value; ‘Develop Capability’ to enact run-time support for the value; and ‘Verify and Audit’, to confirm alignment and compliance to the requirements of the value. (The system-3* component Viable System Model, which represents the closest match to this part of Enterprise Canvas, covers just one aspect of ‘Verify and Audit’, namely random audit of compliance.)

In Taylorism these services are often subsumed into the ‘management’-functions, which can often lead to misunderstandings because the managers themselves must be as subject to the values as is everyone else. It is true, though, that in many cases the core support-group for each value will be regarded as a ‘staff’-function, often reporting indirectly or even directly to the CEO or overall executive; it’s certainly essential for each of these values to have the full backing of the executive, otherwise in practice they end up going nowhere.

Although these validation-services do provide guidance across the enterprise, they are in effect almost orthogonal to the direction-services (‘management’ etc) and to the coordination-services (‘change-management’ etc). Some aspects of these services are often outsourced to other organisations – such as training, to develop capability – and in many contexts the Verify and Audit’ functions must be enacted by an outside organisation, either to support certification or mandated by law. Overall, though, the final responsibility for alignment to each of the enterprise-values must reside within the organisation itself: that aspect of these services cannot be outsourced.

In effect, these services should represent the nodes of a PDCA (Plan / Do / Check / Act) continuous-improvement loop for the respective value, starting at the ‘Act’ node.

- Plan – ‘Develop Capability’ is crucial to embedding the ability to enact support for the value.

- Do – The awareness and capability are applied in practice within each service and service-delivery.

- Check – ‘Verify and Audit’ confirms compliance, or any deviation from required or intended performance.

- Act – ‘Develop Awareness’ is central to taking action towards improving support for the value.

Before any of this modelling-work can make sense, there are some obvious questions that need to be asked:

- What are the enterprise-values? Why do these values apply in this enterprise, and in this organisation?

- Which of these values are explicitly espoused as matter of personal choice, by the executive and/or by others – such as in this organisation’s equivalent of the ‘HP Way‘? Which of these values are imposed on the organisation from outside, as part of a metaphoric ‘license to operate’ within the industry or broader social milieu?

- What differences – if any – exist between the espoused values and the values actually enacted and upheld within the organisation and/or the broader shared-enterprise?

These values should typically be modelled as Value-entities in a row-0 segment of an Enterprise Canvas, attached to the Vision-entity in the model. Within the model, Service-entities for all validation-services should ultimately link back via flow-, composition and realization-relations to one or more row-0 Value-entities.

Given that list of enterprise-values, questions to ask here for each enterprise-value include:

- Validate::Awareness – What support does this service need to develop and establish awareness of the value and its importance to the organisation and enterprise? What services would ensure that this service is aligned to the respective value? By what means are these ‘Develop Awareness’ validation-services for this value delivered to this service? Who or what is responsible for providing these services to the organisation in general, and to this service in particular?

- Validate::Capability – What support does this service need to develop and improve its capability to enact the requirements of the value within the service and its service-delivery? What services would ensure that this capability is appropriately developed, and the capability verified prior to action? By what means – such as training-programmes – are these ‘Develop Capability’ validation-services delivered to this service? Who or what is responsible for providing these services to the organisation in general, and to this service in particular?

- Run-time support within this service – What functionality and other support exists within this service to enact the value within all of its activities and processes? In what ways are the awareness of the value and capabilities to support the value expressed in practice? Since this represents a personal responsibility incumbent on everyone involved, what support exists at run-time to ensure that those responsibilities are upheld?

- Validate::Verify – What support does this service need so as to verify and audit its actual performance in relation to the respective value? What services would ensure that this service has indeed delivered that performance? What records and other sources are needed in this validation-support? By what means are these ‘Verify and Audit’ validation-services delivered to this service? By what means are these ‘Verify and Audit’ services themselves verified and audited for alignment to the value? Who or what is responsible for these services, and how they apply to this service?

As before, identify the services and exchanges in each case. Add these to the model as Service-entities and Exchange-entities, linked to the service-in-focus via flow-relations. Use either containment or composition-relations to link each of these Service-entities to the overall Validation Service. Annotate each flow-relation here with a ‘validate’ label, to indicate that the flow delivers validation-services to the service-in-focus.

Also as before, be careful to avoid falling into layering-mistakes in the modelling process here (again, see ‘A note on layers’ above.) Overall, there are lot of useful insights to be gained here, about the nature of the enterprise, and about architectural risks and opportunities. The key concern to note, as with the other guidance-services, is that the service-in-focus will not be viable – especially over the longer-term – unless adequate and appropriate validation-support is available for each value in context.

Investors and beneficiaries

The Investor and Beneficiary services respectively represent those who contribute value to the service, or to whom value is returned from the service, beyond and outside of the usual transactions of the service’s supply-chain.

These services (or service-relationships) are not covered as such in the Viable System Model. They barely rate any mention in classic Taylorism: the only investors acknowledged there, and also the only beneficiaries acknowledged, are the purported ‘owners’ of the business, who invest money in the business and receive money from it in return.

In practice, even at the whole-organisation level, we need a much broader understanding of the roles of investors and beneficiaries, and the nature and myriad forms of value which they invest or receive. We also often need to explore how the forms of value are themselves transformed within a service. For example, in a business-startup context, people may invest time and skill and effort, and hope to receive monetary return; whereas in a non-profit context, people might invest money in the hope of seeing broader social benefit. The same overall principles apply right down to the level of an individual web-service or the like, though sometimes these value-relationships there can be difficult to identify and even harder to describe!

Note that ‘value’ here has a somewhat different meaning to ‘values’ in the enterprise-values sense: the two terms are often related, but they’re not necessarily the same.

When modelling these aspects of service-viability, we need to be aware that these relationships are often highly politicised, and often bound up with some very muddled notions about ‘rights’ or ‘control’. There are also often very strong pressures – especially in commercial organisations – to either ignore all non-monetary forms of value, or to try to force all forms of value into monetary terms, even when it makes little or no sense to do so. Although others may need to work solely with monetary valuations, for our purposes here we need to model the actual forms of value in each context, in their own terms, prior to any conversion to any other form. Failing to do so will invariably lead to architectural problems that can have serious impacts on overall viability – particularly via anti-clients and other kurtosis-risks.

Questions to ask here include:

- Investor – Who or what invests value in this service, in order to get it started, or to keep it running? What forms of value are delivered as investment in this service? Via what services, relationships and exchanges are these investments delivered to this service?

- Beneficiary – Who or what receives value as a return from this service? What forms of value delivered by this service as returns to its beneficiaries? Via what services, relationships and exchanges are these returns delivered by this service?

- Transformation – What are the differences – if any – between the forms of value that are invested, and the forms of value that are returned? By what means do these value-transforms take place within this service?

- Balance – In what ways and to what extent are the invest and benefit relationships in balance, both before and after transformations of value within this service? What relationships with other services are needed to monitor that balance, and/or to take action to correct any perceived imbalance? If the two flows do not balance overall, what impact would this have on overall viability, both of this service and of other related services?

As usual, identify the services and exchanges in each case. Add these to the model as Service-entities and Exchange-entities, linked to the service-in-focus via flow-relations. If necessary, use either containment or composition-relations to link each of these Service-entities to the overall Investor or Beneficiary Service.

Annotate each flow-relation here with a ‘invest’ or ‘benefit’ label, to indicate that the flow delivers investment of some form to the service-in-focus, or that the service delivers benefits to a beneficiary. An ‘invest’-flow will typically connect either to the Service as a whole, or to the Value-Outlay cell, since the latter represents an abstraction of the activities that manage costs and outgoing payments and the like. For much the same reasons, a ‘benefit’-flow would typically connect either to the Service as a whole, or to its Value-Return cell.

Once again, be careful to avoid falling into layering-mistakes (see ‘A note on layers’). There are some very important and often enlightening insights to be gained here, again about the nature of the overall enterprise, and about architectural risks and opportunities. The key concern to note is that the service-in-focus will not be or remain viable unless it does have adequate and appropriate investor-support, and that – in architectural terms, at least – the balance between investors and beneficiaries is appropriately managed.

Iteration and recursion

At this point we’ve now completed the viability-checklist for that single service-in-focus – the Service-entity with which we started. We could now apply the same checklist-assessment, recursively or iteratively, to any of the Service-entities that we’ve added to the model during this process – everything is a service, so the same viability-principles apply everywhere and at every level.

For obvious reasons, don’t attempt to apply this to everything: by definition, it would take an infinite amount of time to complete the model! Instead, it’s wise to hold to the guideline that we only create a model in response to an explicit business-question, and only to the level of detail needed to answer or respond to that question.

In the same way, it can often be useful to do a drill-down into the details of a specific service, and apply the same viability-assessment at the next level down; or to the next level upward, to a more abstract layer at which redesign and restructure becomes possible. (Or levels – again, iteration and recursion would apply in both directions all the way up and down the layers of abstraction.)

In drill-down or drill-up, though, we need to be especially careful about the distinctions between layers of granularity and layers of abstraction (see ‘A note on layers’ again), because it’s very easy to get them confused here. Going up or down in granularity – composition-relations – is just a change in detail: each ‘child’- or ‘parent’-service will handle a subset or superset of the service-content and Exchange-content of the initial service-in-focus. However, going up or down in abstraction – realization-relations – involves a change in the type of detail that can be described: for example, by definition, row-3 cannot contain descriptions of any specific technology or implementation-method, whereas row-4 can.

Beyond that, though, there are no real restrictions on what we can model in Enterprise Canvas, or why: we’re welcome to iterate or recurse to our hearts’ content, up and down the layers, and anywhere across the enterprise context.

It’s all about story

One last point to finish this Enterprise Canvas how-to.

So far everything we’ve done has probably seemed to be in terms of structure, and relationships between structures: services, exchanges, flows, composition and realization.

Yet there’s another equally-valid way to look at architecture: and that’s in terms of story.

One of the first things we say with Enterprise Canvas is that everything is a service. Yet it’s equally true to say that everything is a story.

Every service is a story, represents a story, has its own story to tell.

Every exchange is a story. Every flow or composition or realization is a story. Every change is a story. The enterprise itself is a story, too. Everything is a story.

When we look at an architecture, yes, it’s all about structure, and dynamics of structure; and it’s also all about stories.

And stories engage; stories draw people in; stories give people a reason to be involved in whatever it is that the service does and delivers, and how and why and where and with what it does so. It’s often in the stories that people tell us that we find the most important clues about what’s working or not-working in the enterprise, and what to do to make it work better. In that sense, the stories matter.

So whenever we look at an architecture, whenever we look at structure, we need also to look at, and look for, the stories that underly and underpin and interweave with that structure. And likewise, whenever we look at the stories, we need to look for the underlying structures that they each imply. Architecture is both structure, and story – and more, of course.

So it’s useful to see Enterprise Canvas not just as a framework for models of structure, but also as an anchor for stories, about the enterprise, about how everything fits together (or not) within the unified whole that is the organisation and its broader enterprise.

Something to work with, play with, even dance with, perhaps, as we further develop our organisation’s enterprise-architecture?

Thanks for directing me to this prior post. It was long, but worth it.

The discipline of articulating services in business architecture terms makes things explicit. It pulls the Wizard from behind the curtain and exposes rationale, purpose, controls, etc.. so they can be accepted and/or challenged – at least open for discussion.

Hiding the details is not helpful and begs the question as to whether the service is thoughtfully constructed. Everyone should know the story! In this way they can be living stories.

This supports network thinking as everyone is a participant in the conversation. Content negotiation as we discussed in the other post gets you semantic reconciliation, ‘truth to power’, controls/governance, and transparency. It’s not just social ‘chatter’, it’s dialog at the level of units of operation.

It’s definitely a dance, choreography of concerns over orchestration of work.

It’s not the end of hierarchy per se, but it opens the door to agility and provides a sense of legitimacy that should fundamentally transform the workplace.

Dave – uh, yes, unfortunately my posts do tend to be long… but at least in this case, as you’ve seen, that amount of detail really was necessary. 🙂

Agree strongly with about ‘service as living-story’, network-thinking, ‘content-negotiation’ and ‘dialog at the units of operation’.

And yes, re “it’s not the end of hierarchy per se”, but rather what I’m looking for, and strongly, is the other meaning of ‘end’, as in purpose (the same sense as in the contrast between ‘ends versus means’). When hierarchy exists solely for its own sake – as seems the case in way too many organisations – then yes, I’d suggest strongly that we need to bring it to an end: but perhaps more usefully as ‘bring it back to functional purpose’ rather than ‘bring it to a sudden halt’. “A sense of legitimacy that should fundamentally transform the workplace” – yes, that’s a very good way to put it.

There’s a lot in this and I’ll need to read it a few more times before I can make sense of it.

Some of the distinctions are truly puzzling – but horses for courses. We all arrange and label things in our own peculiar way.

One of the most worrying aspects for me is no mention of purpose (not the same as vision) in the extended-Zachman map, or elsewhere for that matter. I find it hard to believe in a model when something so fundamental is omitted. Maybe it’s covered and I’ll see it when I read the article again in the morning. Or is it a case of Stafford Beer and “the purpose of a system is what it does”? and therefore not worthy of mention?

Enough of my reflex reactions. Thanks for making these ideas available to us. I will reflect and reconsider.

Jack

Thanks, Jack.

“One of the most worrying aspects for me is no mention of purpose (not the same as vision)” – I’ll admit I’m confused here. The way I structure vision is that it is the driving purpose, so I don’t see any difference. (In the extended-Zachman, ‘Why’ is then the driver for the view looking ‘upward’ in the layering, and ‘How’/’What’ is the driver for the view looking ‘downward’.) What have I missed?

I describe the elephant in a different way than you do, I think in terms of VSM and image. I ask, What does it look like? From image comes identity and from identity comes purpose, thus, I ask for the image first.

I am also trying to fit it in with Stafford Beer’s methodology of defining the “System in Question, and drawing recursions of it’s elements.

I use the Business Model Canvas as a elaborations of the VSM, and I am now looking at how you have extended the model to deal with service viability.

This is a long article and it will take me some time to digest. Thanks for writing it.