Competence, non-competence and incompetence

One of the key reasons why I’m so vehemently against any-centrism and suchlike revolves around the question of competence – or, more usually, the lack of it.

Competence is where someone knows what they’re doing, and does it. And, oddly, often don’t bother to say that they’re competent – perhaps because they don’t need to say it, their actions say it well enough instead. The outcome of competence is fairly certain, even in contexts of high uncertainty.

Non-competence is where someone doesn’t know what they’re doing, and will either not do it, or will do the best they can, yet with the explicit intent to use it as a learning to improve their competence. Importantly, they will usually say that they don’t know what they’re doing. The outcome of non-competence is uncertain, even in nominally-certain contexts, but at least we are aware of the risks.

Incompetence is where someone doesn’t know what they’re doing- i.e. is non-competent to do the task – but either purports and/or believes themselves to be competent. They will usually say that they are competent, even though demonstrably they are not; they claim to be responsible, yet have limited ‘response-ability’. The outcome of incompetence is fairly certain, and frequently dire, yet lack of awareness of the risks is often rampant, or in some cases the risks actively concealed.

Someone who is non-competent can become competent by learning the respective skills, or be competent by proxy, via finding someone else who is competent at doing the respective type of task. I treasure my non-competence, because it means there’s always more for me to learn. And as an enterprise-architect, I am, almost by definition, non-competent in much if not most of the detail-aspects of areas that I need to cover: hence one of my key competencies is the ability to learn enough of a new area fast enough to be able to guide meaningful exchanges between people who are fully competent in some detail-area but are not competent in others with which they need to connect.

Yet one of the key criteria for non-competence, and to separate it from incompetence, is a willingness to accept that we are non-competent, and say so. If we’re not aware that we’re non-competent, we automatically increase the risk of being incompetent. And if we know that we’re not competent, yet somehow ‘need’ to claim that we are competent, we would, again, automatically be incompetent – with a very high risk of inappropriate or ineffective outcomes of the work.

In part it’s a cultural problem: the risk of incompetence increases wherever a culture exhibits any of these characteristics:

- prioritises content over context, ‘truth’ over context-dependent usefulness

- has an insistent ideological base (leading to the same as above)

- is typified by rampant egotism, self-advertising and self-centrism

- is frequently swayed by tides of hype and ‘following after the latest fad’

- displays an almost desperate need to be ‘right’

Unfortunately, all of these attributes are extremely common in business, and in many cases are actively prized… By definition, they’re also more likely to be common in any ‘truth’-oriented domain, one which operates primarily on ‘true/false’ decision-making – hence, in practice, the tendencies towards IT-centrism and finance-oriented business-centrism, both of which rely on simple true/false logic for most of their operational decisions.

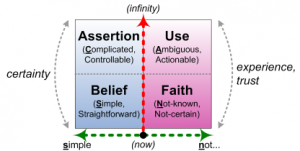

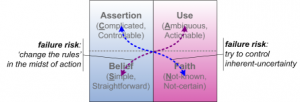

In SCAN terms, all of these are where the Simple certainties of Belief – either as ideology and/or as self-belief – are inappropriately applied to the far side of the Inverse-Einstein Test, where the uncertainties of the Ambiguous and the Not-Known cannot be avoided.

This gives us a dysfunctional ‘diagonal’ decision-path, where Assertion is imposed on the Not-known, or Ambiguity ‘solved’ by arbitrary Belief:

Yet the real problem here is somewhat more subtle:

- someone who is competent will typically not bother to say so, but will just get on with the work instead

- someone who is non-competent will typically say that are not competent, but will often actually be adequately-competent, or at least willing to learn to become so

- someone who is incompetent will typically claim that they are competent, and will usually not be willing to learn how to become so, because to do so would betray to themselves and others the fact that they are actually not competent

Which, in practice, leaves us with a huge dilemma:

- those who do not claim to be competent usually are competent

- those who do claim to be competent frequently are not competent

Hence, again, the kind of mess that we see so often in enterprise-architectures, wherever IT-centrism, business-centrism and the like predominate… Oh well.

Comments, anyone?

Reminds me of what Donald Rumsfeld said –

There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know.

There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know.

But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don’t know we don’t know.