Modelling mixed-value in Enterprise Canvas

One of the more subtle problems in enterprise-architecture – in English-language, anyway – is the distinction between values (plural) and value (singular, but often used as plural). The Enterprise Canvas frame provides several useful methods via to disentangle an existing values-mess, and prevent getting into that kind of mess in the first place.

In Enterprise Canvas, we assert that everything is or represents a service. Ultimately, each service serves the overall vision or purpose of the shared-enterprise, which often extends far beyond the boundary-of-control of the organisation itself.

The values of the shared-enterprise derive from and express that vision or purpose. Hence these are values that the organisation must respect if it is be and remain in business within that shared-enterprise. For example, the TED vision of “ideas worth spreading” is expressed in practice through values such as responsibility, respect, clarity, connection, engagement, passion for ideas and production-quality – values that can be seen in practice in just about everything for which TED has either direct responsibility or oversight (such as the independent TEDx conferences).

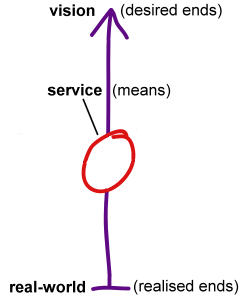

In the sketch-notation for Enterprise Canvas, we typically model these as the ‘vertical axis’ through the service, connecting intent to real-world results:

In detailed practice and implementation, the values are expressed in more actionable form as principles. (See Chapter 23 ‘Principles’ in the TOGAF 9 specification for a good summary of how to define and structure actionable principles.) Principles are used to guide decision-making in the face of uncertainty at every level of abstraction, from strategy to tactics to real-time operations.

Value is what is passed around the enterprise, as exchanges between services, in order to achieve the overall aims of the shared-enterprise. In effect, exchanges of value within the enterprise align with and contribute to the values of the enterprise.

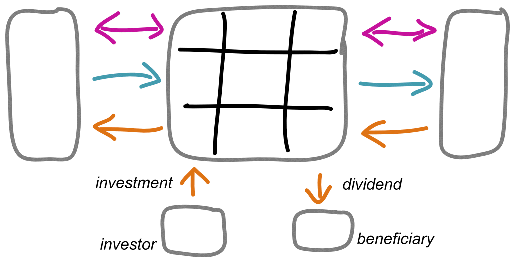

In the sketch-notation for Enterprise Canvas, we typically model most of these exchanges of value as the ‘horizontal-axis’ through the service, connecting with other services before, during and after each main-transaction. We would sketch a simple supplier-self-customer supply-chain model – such as is typical in Business Model Canvas – in a format somewhat like this:

To make better sense of that ‘horizontal’ flow of value, we often partition the service into a three-by-three matrix of ‘child-services’ – the matrix being formed from a time-dimension (before, during and after) and an orientation-dimension (inbound [service-consumption], self [value-creation] and outbound [service-provision]):

Often in modelling with Enterprise Canvas we’ll use generic labels for each of these clusters f ‘child’-services. For our purposes here, the cluster we need most to focus on is value-governance, which acts mostly (though by no means exclusively) on the back-channel, the ‘after transactiuon’ flows:

The service also needs to connect to other guidance-services, to help keep the flow of value on track to the enterprise-values. The guidance-services include:

- direction-services – the strategic, tactical and operational forms of classic ‘management services’

- coordination-services – guiding end-to-end connection of processes that intersect with multiple services, often across or between organisational silos

- validation-services – services that assist in building awareness, capability and action, and verifying and auditing that action, on ‘pervasive’ value-themes such as knowledge-management, health, safety and environment, efficiency, reliability, security and financial probity

In Enterprise Canvas sketch-notation we’d typically show the guidance-services like this, tagged with the respective symbol:

Of the guidance-services, probably ‘direction-services’ connect must strongly with the ‘Value Governance’ cluster of child-services, though by definition all of the guidance-services must connect with every part of the service.

So far so good: value connects to values.

Yet there’s another set of service-relationships that we must not overlook: the relationships with investors and beneficiaries. In Enterprise Canvas sketch-notation we’d usually show them like this:

Investors provide forms of value that are different from the forms of value that flow ‘horizontally’ around the shared-enterprise, but may be needed in order to start up, operate and maintain the service. The obvious example is financial investors, where the value of the investment is usually described in monetary terms. Yet there are many other forms of value that may be involved: for example, a community invests trust and, often, hope in an organisation doing business in its locality; families of employees may invest very real energy to keep them working there, and so on.

Beneficiaries receive some of the returned-value from the service, typically diverted from the flow in the backchannel, as a ‘dividend’ or suchlike. Again, the obvious example is value in monetary form, but again there are many other possible forms of value: civic pride, for example, or the shared pride of employees’ families.

Yet there are two fundamentally important traps to note here.

One is that the Investors and Beneficiaries may be different people. For example, an ‘externality’ occurs whenever one or more groups invest their own forms of value, but another group extracts all or most of the available value in one preferred form only, damaging or destroying most or all other forms of value. Again, the obvious example is financial: the community and employees invest their energy and their time, but the shareholders – as nominal ‘owners’ – claim the ‘rights’ to possess all of the returned-value, which somehow must also be converted to monetary form. A key role of value-governance is to identify such mismatches, and to bring them back into some form of balance that is acceptable to all parties – otherwise the service will fail over the longer-term.

(Somewhen I’ll have to write a post about anti-clients, anti-value, anti-Investors and, especially, anti-Beneficiaries. But that, as they say, is another story for another time!)

The other trap is that whilst the Investors’ and Beneficiaries’ forms of value may be needed by or deliverable by the service, the values of the Investors and/or Beneficiaries may not align with those of the service’s shared-enterprise. In enterprise-architecture we do need to respect the drivers and needs of Investors and Beneficiaries, but it may be essential to keep the value-systems separate. If we don’t, we risk ending up with the kind of lethal mess where, for example, attempts are made to measure everything in monetary terms, blocking the actual forms of value that traverse ‘horizontally’ across the enterprise-space.

Michael Porter described one form of this trap as“the obsession with shareholder-value is the Bermuda Triangle of strategy, in which companies sink without trace”. There are many forms of this trap, though: look around at much of mainstream politics and politically-motivated regulation these days, or the sad disaster-area that is the ‘rights’-discourse… It’s definitely a real challenge for any enterprise-architect.

In short:

- values guide decision-making and appropriacy of choices within the shared-enterprise

- value is what flows around, through, to and from each service in the shared-enterprise

So in each architectural context, be clear what values and forms of value you’re dealing with, and how and where and why – and don’t mix them up!

Tom,

Sometimes you are literally too brilliant!! This is a great post but I have to be honest (I’ve read all of your books and) you were beyond my comprehension a couple of times in this post. I am but a mortal after all.

Looking forward to the anti-post!! 🙂

“You were beyond my comprehension a couple of times in this post” – oh. Oops… Sorry.

Trouble is that I forget, way too often, that what’s ‘obvious’ to me isn’t obvious to anyone else at all. And I try cram so much into every post, with so many ideas that depend on other ideas that depend on other ideas that I might remember but others probably don’t, that it can sometimes be a bit (or a lot?) too difficult to follow. Oh. I Must Do Better Next Time, etc. Oh well. My apologies, anyway?

“I am but a mortal too” – yeah, that’s the problem. Not just in that sense, but at my age I’m acutely aware of just how mortal I am, which brings on a quite different kind of urgency… 🙁 – in particular, an urgent need to get things down in some kind of usable form whilst I still can. Which means that things can get a bit rushed and a bit too compressed. Oh well. Again, my apologies.

“What’s obvious to me” … One of the great rules from Made To Stick by Chip & Dan Heath.

We forget that we know something that someone coming in cold doesn’t.

Singular Value is the exchanged “price”

Plural Values is vision and ethics that permeates everything they do.

Right?

Hi Pat

“Singular value is the exchanged ‘price'” – actually, it’s a lot more than that, and price-as-value is usually only one quite small part of it.

Remember the old expression that “people do not want quarter-inch drills, they want a quarter-inch hole”: it’s the hole that is the perceived value, not the drill – and the price of the drill comes quite a long way further down the track, as a secondary or even tertiary aspect of the overall ‘value-proposition’. The ITILv3 specification describes it in a very similar way: ‘people do not want products or services as such, but the satisfaction of a perceived need’. In enterprise terms, ‘the satisfaction of a perceived need’ is the effective source of perceived value.

In terms of Enterprise Canvas, in most business-models (essentially, anything other than finance-industry etc), price is a typically a tertiary concern in the ‘before-transaction’ interactions, typically a secondary attribute of value in protocols for ‘main-transaction’ interactions, and a primary concern in only one aspect of the ‘after-transaction’ backchannel (the ‘accounts-receivable/accounts-payable’ completion-thread).

When people artificially elevate price as ‘the value’, all of the other architecturally-crucial nuances get pushed out of the picture – which is why, architecturally speaking, focussing on price or money alone can be such a serious problem.

Price can be a ‘singular value’ – but the moment we think it’s the ‘singular value’, we’re already in deep trouble.

I hope that that clarifies the difference?

Exchanged price is an example of “singular” value. We usually focus on commercial companies and their interaction with extended enterprise (highest level for the company). In this level and in this context companies have to think in terms of financially measurable values. This is not suprising when you consider the bigger picture (economics, capitalism, etc).

However when you are in a different context value can be something which cannot be directly measured by price. Tom likes to give the example of NGO. I like to give example of customer service. Customer service increases customer satisfaction and trust. You cannot measure trust of a customer with a price (at least in my understanding of “price”, native speakers any help?).

Please don’t forget canvas can be used in any service (not only commercial) and in any size of service (not only companies, but also departments, teams, machines, programs, etc). I would argue value is more often cannot be measured with financial metrics. What do you think?

Hi Iyigun

Yes, exactly – and very strongly agree with your comments on customer-service’. I’m going to highlight this note of yours: “You cannot measure trust of a customer with a price”.

(Re ‘native speaker’, to my mind the way you put it is pretty much how how it would be expressed by a native-English speaker, so no translation-problems there. For me, anyway.)

“I would argue value is more often cannot be measured with financial metrics” – exactly, and strongly agree (see my reply to Pat Ferdinandi just above this). The usual attempts to force-fit everything into a monetarist view of the world are what most often destroy value rather than create it.

I don’t know why so many people have difficulty with this fact, but clearly they do – hence tools such as Enterprise Canvas, which aim to surface (make-visible) these hidden yet highly-erroneous assumptions about the nature of value.

—

On “Exchanged price is an example of ‘singular’ value. We usually focus on commercial companies and their interaction with extended enterprise (highest level for the company). In this level and in this context companies have to think in terms of financially measurable values.” This is one I’ll need to go into in more detail, which probably means yet another blog-post (sorry!). The short version is described in part by my reply to Pat above – that focussing too much on money in transactions/interactions ends up distorting the picture so much that there’s no way it can make architectural sense – but also the effects of a myriad of other distortions introduced by the ‘necessary’ structures of a money-based possession-economy, and by the ‘financial-investor-as-exclusive-possessor’ typical of a money-based ‘stockholder’-capitalist model.

What I recommend always is to model the architecture in terms of mutual-responsibilities, and only then start to design overlays to cope with particular societal/socioeconomic exchange-models. The reason for this is that the underlying mutual-responsibilities are relatively stable – i.e. the actual core of the transaction/interaction – whereas the subsidiary mechanisms to deal with the socioeconomic overlay are merely an extra set of attributes that we attach to that core, with different attributes used for different exchange-models.

For example, the core of an exchange of goods or services is exactly the same whether we use a payment-model, a barter-model, or an intra-company non-monetary model: the economic-exchange models are just overlays on top of that core. Over-focussing on the attribute-mechanisms (e.g. payment) rather than the core (perceived-value) makes it very hard to shift between different exchange-mechanisms – for example, from a direct-exchange or shared-resource intra-company model to a charge-back intra-company model and thence to an out-source, in-source or mixed-source intra/inter-company exchange-model. In other words, the over-enmeshment with the money-system is just a classic example of architecturally-fragile ‘bundling’: we need to be able to ‘unbundle’ it in order to develop architecturally-robust and architecturally-reusable service- and/or product-models.

Hope this makes some sense, anyway?

The part about core values of the organisation as reflected in it’s actions is as always interesting. However the second part that focus on pass by value is somewhat problematic. I’d suggest that it may be better to re-focus our interpretation on pass by result instead.

Hi Jörgen

On “pass by value is somewhat problematic. I’d suggest that it may be better to re-focus our interpretation on pass by result instead”: I do take your point there – we definitely need to focus on result. Yet perhaps the key here is that the ‘perceived value’ of ‘the result’ is assessed in terms of enterprise-value – hence we need to understand the meaning of ‘value’ within the enterprise in order to identify the effective meaning of ‘result’.

On “the part about core values of the organisation as reflected in it’s actions is as always interesting”: my point is that we need to be really careful here. The values in this context – and hence the effective definition and meaning of ‘value’ – are those of the shared-enterprise (‘outside-in’, from customer etc perspective), not solely those of the organisation itself (‘inside-out’, organisation-centric). In order to succeed within the shared-enterprise, the organisation must align at least some of its own vision and values with those of the shared-enterprise – otherwise there is literally no means to establish a viable connection with the shared-enterprise and thence ‘the market’. If we get this the wrong way round – as most companies still seem to do – we will have a business-architecture and enterprise-architecture that is guaranteed to be problematic and to fail unpredictably in ‘unexpected’ ways. You Have Been Warned etc? 🙂

Very interesting approach to distinguish’values’ and ‘value’ and show they can (should) be used for company governance !

I am currently collaborating with experts in different fields of company performance using a view about ‘value’ that you may be interested to consider ?

For us, the value of something for somebody is the ratio between its usefulness and costs. The more the thing is useful and fulfills needs, the more valuable it is perceived. The more it costs (in money or other resources) the less it is valuable. The value of something is then the perceived value by all its stakeholders : users, , owners, manufacturers, distributors…

This can be applied to product/service design, leading to methods like Value analysis It has also been applied for years to industrial and administrative processes, IT systems, purchasing, communication, coaching, … and even to company management and strategy, leading to methods like lean, business analysis, BSC, Blue Ocean …

As you propose in Entreprise Canvas, a company’s value can be defined by the value it offers to alll its stakeholders :

– clients would receive products/services fullfilling their needs (+ other performances), against a cost (+ other efforts …)

– a supplier would receive money (+ security, image …) against supplies (+ innovation…)

– employees would receive money (+ employability, status …) against time, skills and motivation

– shareholders would receive money (dividends or share price, + image …) against money (earlier funding, hopefully less than received…)

– environment would receive pollution (?!) against life conditions (water, air, sun…)

– civil society would receive indirect effects from economical activity (local stores and employment, education, pride …) against life and work conditions, image …

– administration would receive taxes against services (infrastructures …)

So we are able to precisely define and dimension the value of a company, a service, a product, etc. As you mention, this value is not dimensioned in money alone : if costs can be measured in money (but what about environmental costs ?) usefullness most often has to measured in something else !

I’ll mention you post on our ‘Valeur(s) & Management’ blog, presenting (sorry, in French only for the moment) numerous approaches targeting this topic of ‘value’ for companies performance improvement.

I’ll be happy to share with ytou about all this !

Olaf de Hemmer

President – AFAV > Value(s) & Management

Hi Olaf – very good point about ratios. Probably the best person to talk with about that would be Chris Potts: much of his enterprise-architecture work – as described in his books ‘fruITion and ‘recrEAtion‘ – focusses on business-ratios of various kinds.

As we both agree, the selection of value-criteria for ‘cost’ needs to be a lot broader than money alone! And I do like your concept of ‘usefulness’: that’s a theme I hadn’t thought of, and it’s a very good test of value (especially perceived-value).

Many thanks indeed for mentioning me on your ‘Valeurs et Management’ blog – much appreciated! My French is just about good enough to read your blog, but unfortunately not good enough at present to write in French: if you want to translate any of this blog into French, please feel free to do so?

Thanks again, anyway.