Costs of acquisition, retention, de-acquisition

How much does it cost to acquire a customer? To retain a customer? To lose a customer? And in what sense of ‘cost’?

In part this one was triggered by reading through my relatively-new copy of Business Model You, and reflecting on the narrow money-only model of revenue and cost that pervades the original Business Model Canvas and its concept of ‘business-model’:

We defined ‘business model’ as ‘the logic by which an enterprise sustains itself financially’. Put simply, it’s the logic by which an enterprise earns its livelihood.

In reality, money is a form of cost, and a form of revenue – but in either case it’s by no means the only one. And the attempt to conflate all of those other types of cost or return solely into monetary form is a direct cause of all manner of otherwise-avoidable business-disasters.

None more so, perhaps, in sales and marketing. Every salesperson or marketer would recognise that there is a cost to acquiring a new customer, and likewise a usually much-lower cost to retaining an existing customer. However, few seem to recognise that de-acquisition – losing an existing customer – can carry far higher costs than merely the financial opportunity-cost of foregone future trade: and those costs can sometimes be high enough to bring down the entire business. In other words, not something that’s wise to ignore…

To make sense of this one, we need three things:

- a broader sense of ‘the enterprise’

- a broader understanding of ‘value’ – beyond a solely monetary sense – and how it intersects with business-services

- a broader understanding of where ‘cost’ and ‘profit’ arise in a business-service – and for whom

On the nature of enterprise, I use a much broader definition than that implied in Business Model Canvas: ‘the enterprise’ is not the organisation alone, but the overall business-domain or business-purpose within which the organisation operates. In essence, ‘the enterprise’ is a desire, a promise, an ‘ends‘ that is shared with others; the organisation is merely a means via which, in working together, people can reach towards those desired-ends.

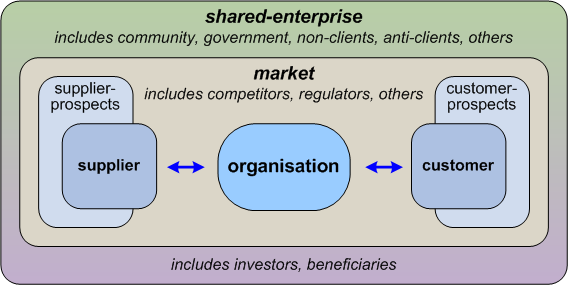

If we say that the organisation ‘is’ the enterprise, there’s nothing to share with anyone else, and hence no reason for anyone to do business with the organisation. Or, to put it the other way round, the idea that the organisation is not ‘the enterprise’ is what, for others, makes doing business with organisation both possible and, perhaps, desirable. I usually illustrate this by showing ‘the enterprise’ separated from the organisation first as its transactions with its supply-chain or value-web, then its overall market relationships, and then outward to a much broader shared-space bounded by interactions rather than transactions – which also includes its investors and beneficiaries:

The shared-enterprise is defined by that desire or idea or promise, which in turn identifies the values of the enterprise – and which in turn also imply success-metrics in relation to the promise and its values.

To do business with others, an organisation presents a value-proposition – which in practice must be linked to the promise and values and success-metrics of the shared-enterprise.

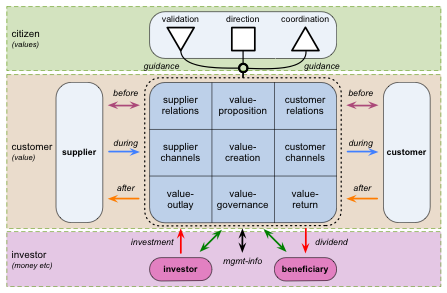

Once we fully understand this, the distinctions between ‘values’ (enterprise) versus ‘value’ (that which is exchanged between services) versus money (merely one type of ‘cost of doing business’ within a money-based possession-economy) also become more clear, and hence the different service-relationships each service needs in order to keep these all in appropriate balance. Which we could summarise visually as:

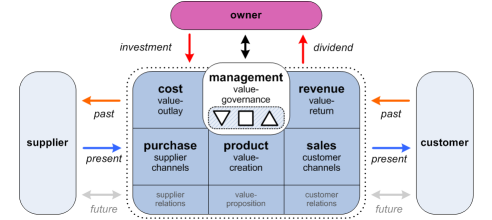

In practice, though, what often happens is that an organisation – or even an entire culture – fails to comprehend value in anything other than monetary terms, and hence uses money as a proxy for ‘value’ in all of its relationships with the shared enterprise. There are often huge pressures to do this if financial-investors are given too much weight, as ‘the owners’ – which gives rise to an often seriously-dysfunctional upside-down and back-to-front model of organisation-as-service, where monetary ‘shareholder-value’ and suchlike take priority over the values and value-flows that make the monetary-return possible in the first place:

To understand why this is so dysfunctional, we need to look at how service-relationships actually work. If we take a money-only concept of business, it’s easy to cut off the view at a very simplistic transaction-only notion of ‘the market’: we grab someone’s attention via marketing, do the transactions of the sales, take the profit, and loop back for the next punter:

Even here there’s an attention-cost as well as a material (‘moneyable’) cost: every skilled salesperson knows that the wrong kind of attention-grabbing can cost sales, and hence hit the profit. It’s often easy enough to ignore that as a form of cost, though, and just hold the focus on ‘value-as-money-as-value’.

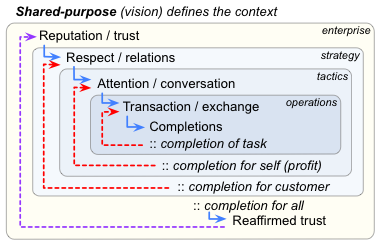

But the reality is that markets are much more than just transactions. As the Cluetrain Manifesto famously put it, “markets are conversations”; they also express and enact relationships, and shared-purpose too. And all of have their own roles and interactions across the shared-enterprise – which necessarily dictates a much broader view of the overall service-cycle. In somewhat simplified form:

Reputation and trust provide the ground for respect and relations, which in turn provide the ground for attention and conversation about value, and hence a proposition about value, which in turn can form the basis for transaction. And at the end of the transaction, we need to ensure that all of these concerns are satisfied – not just the monetary aspects of transaction.

Everything revolves around value as defined by the ‘promise’ of shared-enterprise; and everything begins and ends with trust – not money.

(As an aside, an over-focus on money alone will almost always lead to the ‘quick-profit failure-cycle’:

In practice this short-cut version of the service-cycle slowly loses its connection not just to trust, but to any sense of purpose or values, any links to people either outside or within the organisation, and even any clear sense of policy or, eventually, any sense of legality. In short, it invariably devolves into a slow-suicide for the respective business: so don’t do it!)

When we look at this in terms of costs and revenues, we can reframe this service-cycle in terms of sets of related dimensions. (What follows is definitely over-simplified – in reality the dimensions always interweave with each other much more than is implied here – but this is probably the best way to describe the overall scope of the context.) Moving outward from the transaction-oriented core:

- transaction-economy: primarily physical assets or ‘things’ (asset-characteristics: alienable, exchangeable) – implies resource-costs, ‘compensation’ for transfer of ‘right of possession’

- information-economy: primarily virtual assets or information and attention (asset-characteristics: non-alienable, exchange-via-copy) – implies potential costs of information-dilution or information-distortion, ‘compensation’ for ‘right of access’ to information

- attention-economy: mix of virtual assets and relational assets (characteristics: constrained by information, relationship and available time) – implies costs in terms of non-exchangeable and non-reimbursable attention and time

- relation-economy: primarily relational assets (asset-characteristics: non-alienable, non-exchangeable, exists between two real [physical] sentient parties) – implies costs in terms of time and of creation and maintenance of relationship, or opportunity-costs etc on loss of relationship

- purpose-economy: primarily aspirational assets (asset-characteristics: non-alienable, non-exchangeable, exists from real [physical] sentient party to [virtual] idea, belief, memory or sense of identity or belonging) – implies costs in terms of trust, purpose, ‘commitment-fatigue’, ‘change-fatigue’ or burnout

- the attention-economy provides the crucial bridge between the parts of the service-cycle that deal primarily with exchange-based transactions (things, information) and those that deal primarily with interactions around non-exchangeable assets (relational, aspirational)

Yeah, I know – that lot all sounds a bit abstract. But to bring it back more towards the practical for the service-cycle – even if still somewhat abstract – reinterpret these in terms of the set of interactions that set up the core service-transaction, and the set of completions that close everything off after that core-transaction:

— set up reputation/trust: The service-provider (‘the organisation’) and service-consumer (‘the customer’) carry various costs in search and discovery to identify mutual interest and mutual values, typically as indicated by mutual alignment to the enterprise-vision. The linkage here is primarily in terms of aspirational-assets (‘purpose-economy’), via interactions through the ‘before‘-channels.

— set up respect/relations: The organisation and the customer identify shared understandings of value and success-metrics for any mutual service-transactions. Both parties carry various costs in value-identification. The linkage here is primarily in terms of relational-assets (‘relationship-economy’), via interactions through the ‘before‘-channels.

— set up attention/conversation: The parties engage in conversations to identify potential requirements for service that the customer needs and the organisation can deliver, described in terms of the previously-identified vision and values (‘value-proposition’). Both parties carry costs in terms of service-identification and conditions and expectations of service. The linkage here is primarily in terms of relational/virtual-assets (attention: ‘attention-economy’) and virtual-assets (conversation/information: ‘information-economy’), via interactions through the ‘before‘-channels.

— set up transaction/exchange: The parties engage in transactions that enact change-as-experienced (‘service’) and/or transfer of exchangeable-assets (‘product’). The linkage here is primarily in terms of physical-assets and/or virtual-assets (‘transaction-economy’), via interactions through the ‘during‘-channels (which may also create and/or change relational– and/or aspirational-assets – for example, to enable a business-relationship, or to create and confirm an individual’s membership of a group or community).

— completion of transaction-tasks: Everything is complete in terms of raw service-delivery – in other words, everything that goes through the ‘during‘ channels of the Enterprise Canvas.

— completion for self (organisation’s profit): The balancing-return does come back from the customer via the ‘after‘-channels. The forms of value exchanged may not be – in fact often aren’t – the same as those in the ‘during‘ channel (for example, monetary payment for ‘services rendered’). They may also be different forms the forms of value forwarded on as ‘dividend’ to service-beneficiaries. This means that there may be significant ‘value-translation’ required to move the returned-value into the respective forms. The difference between the overall operating- and transactional-costs and the returned-revenue represents the service’s effective ‘profit’ or ‘loss’.

— completion for customer: Together, provider and customer establish that the customer’s expectations for service-provision have been satisfied.

— completion for all: Together with other stakeholders – albeit often only implicitly – provider and customer establish that the whole service-cycle was appropriately aligned with and supported the success-criteria of the overall vision and values of the shared-enterprise.

Each of the ‘set up’ stages sets up expectations of quality-of-service, of the proposed value of the service (hence ‘value-proposition’) to the customer.

Each of the ‘completion’ stages represents assessment of the actual quality and value of service-as-delivered and service-as-received. (Note that for Enterprise Canvas and the service-cycle, we usually remove the common distinctions between ‘product’ versus ‘service’ by saying that a product represents a kind of ‘proto-service’, a promise of future delivery of some actual service or self-service.)

If any of those assessments fails – if any party considers themselves ‘short-changed’ in terms of those expectations – then there is a non-monetary cost, in terms of damage to the aspirational- and/or relational-assets created or maintained during the set-up phases. To put it in simple business-terms, there is damage to the willingness to come back for repeat-business, and/or damage to reputation, such as in non-recommendations or anti-recommendations to other potential service-consumers and/or service-providers.

— incompletion of transaction: dissatisfied provider. Up till this point, the costs of the service – in time, resources, attention, effort, money, whatever – will usually have been borne by the service-provider (though this varies somewhat in prepayment-scenarios, where the ‘after‘-channel interactions sort-of come before some or most of those on the ‘during‘-channel). If the balancing-return (‘revenue’) doesn’t come back from the customer, those costs will be classed as ‘non-recoverable’ – nominally the organisation’s problem and organisation’s risk. If the return-transaction doesn’t happen, the relationship between provider and customer will probably be broken from the provider’s side, describing the customer as a ‘bad risk’ or suchlike – in other words, a refusal to engage in future attention, relations or shared-purpose.

— incompletion of attention: dissatisfied customer. This usually happens when the provider drops attention as return (payment etc) has been received through the back-channel (customer-to-provider ‘after‘-channels). In effect, the conversation is cut off before any check has been made as to whether the customer is satisfied with service-delivery. This kind of failure will often create betrayal-anticlients – former customers who feel ‘betrayed’ by the service-provider, and who will actively dissuade others from engaging in interaction or transaction with that organisation.

— incompletion of relations: dissatisfied customer and/or provider. This typically happens when either party simply ‘walks away’ after the interaction, without completing closures that would maintain the person-to-person or person-to-organisation relationships that would enable fast re-establishment of relations on a subsequent iteration of the service-cycle. The best outcome of this kind of failure is that, in effect, the client becomes a non-client, hence imposing on either or both parties the new-client acquisition-costs rather than the (usually much lower) existing-client retention-costs for the next service-cycle. At worst, customer and/or provider may become active betrayal-anticlients for each other.

— incompletion of purpose: dissatisfaction across the shared-enterprise. This typically happens in organisations with a ‘push-marketing’ model and a ‘sales at any cost’ culture: they try to acquire all and any possible customers, regardless of whether there’s an appropriate fit to the actual (i.e. values-based, not ‘feature’-based) value-proposition or to the values and success-criteria of the overall shared-enterprise. Failures of this kind not only create bad-client problems for the organisation, but also risk creating inherent-anticlient challenges against the provider and/or customer across the market-space and the whole shared-enterprise. Such inherent-anticlient challenges may be expressed in forms such as blacklisting, retroactive legislation, active constraints and even ‘pariah’ or ‘public-enemy’ status – as can be seen at present in common public attitudes towards ‘the 1%’ (at either end of the socioeconomic scales) and towards the banks and other financial institutions.

Practical implications for enterprise-architecture

As usual (sorry…), all of that was perhaps a bit too abstract – mainly because I’m trying to cover the whole context in all of its possible forms. At a more concrete level, we can bring at least some of these down to some simple tests for service-design and service-completion:

- Are the vision and values of the shared-enterprise identified and explicit? (Remember that this is the shared-enterprise to which the organisation aligns itself – not the organisation itself.) Failure to do so means that there’s means to establish criteria against which any value-proposition may be tested. [This is the first part of the ‘set up reputation / trust’ stage in the summary above.]

- Are the success-criteria for the shared-enterprise identified and explicit? Failure to do so means that the only apparent criteria for ‘success’ will be blurry notions of ‘customer-satisfaction’ and suchlike (which can sort-of be used to guide service-review and service-improvement), crude non-qualitative metrics such as short-term financial-‘profit’ (which can’t be used to guide service-design), or even more blurry externally-driven notions such as ‘shareholder-value’ (which definitely can’t be used as guides for service-design). [This is also part of the ‘set up reputation / trust’ stage.]

- Are the provider’s value-propositions aligned with the vision, values and success-criteria of the shared-enterprise? Failure to verify this means that the effective success-criteria will default to lowest-common-denominator types such as ‘cheaper’ – often entrapping the provider (and customers too) into a dysfunctional-competition ‘race to the bottom’. [This is another key part of the ‘set up reputation / trust’ stage.]

- Are both provider and customer clear that they share the same (or similar-enough) definitions of ‘success’ in relation to any provision of service? Failure to get clear on this means a near-certainty that one or other of the parties – or both – are going to be dissatisfied with the end-results of service-provision. [This is the end-point of the ‘set up reputation/trust’ stage and the start of the transition to the ‘set up ‘relations / respect’ stage.]

- Are both parties aware of the costs of setting up and maintaining a service-relationship, and willing and able to bear their part of those costs? (Remember that ‘cost’ here is defined in terms of the enterprise-vision, values and success-metrics: money is at best a poor-quality proxy for most such costs, and is not valid or usable at all for many types of cost – skills and competence, for example, or non-replaceable resources or lives.) Failure to clarify this at the start leads almost invariably to someone feeling that they’ve been ‘short-changed’ – and especially so if someone’s been foolish enough to try to use money as an inappropriate proxy for non-monetary costs. [This is a key part of the ‘set up relations/respect’ stage, also starting to transition to the ‘set up attention / conversation’ stage.]

- Are both parties aware of the need for and costs of ‘paying attention’, to clarify actual service-capabilities and service-needs? Failure to get clear on this before and during service-delivery usually leads to excess costs – of many different kinds – for one or both parties, and usually dissatisfaction-costs as well. (The requirement to pay attention during service-delivery arises because needs often change, or are discovered, only within and as a result of the interactions of service-delivery itself. Note also that there are strong reasons why the term ‘pay attention’ exists: it represents real non-monetary costs that cannot be avoided if service-delivery is to be successful.) [This represents the core of the ‘set up attention / conversation’ stage; coupled with cross-checks to agreement about the values in relation to the provider’s value-proposition, this also establishes the ground for the transition to the ‘set up transaction / exchange’ stage.]

- Are both parties able and willing to keep track of variances during service-delivery, and to compensate and adjust for them accordingly? There are real responsibilities here – literally ‘response-abilities’ – without which variance-costs are likely to become hidden until too late to rectify, again leading to dissatisfaction on one or both sides of the relationship. [This is a key part of the ‘set up transaction / exchange’ stage.]

- Are both parties able to identify and agree upon the start-point and end-point of expected and actual service-delivery, and act upon it accordingly? Failure on either side to identify these will lead to excess costs on one or both sides – and, again, dissatisfaction. [The start-point represents the end of the ‘set up transaction/exchange’ stage; the end-point represents ‘end of transaction-tasks’ in the summary above].

- Are both parties able to identify what needs to be done and/or delivered to bring the transactions and interactions to a full completion that will align with the enterprise-vision and reinforce mutual trust? Failure to get clear on that will all but guarantee that someone will be dissatisfied… [This clarifies what needs to get through the ‘after‘-channels, and sets up the rest of the ‘completions’ stages.]

- Once the provider has achieved satisfaction, do they then confirm that the customer has achieved satisfaction? Failure to do so is one of the most certain ways to create droves of active anticlients. (Note that this may need to be repeated at various intervals in order to verify longer-term satisfaction: a product that works well at first but fails earlier than expected is likely to lead to the customer feeling ‘short-changed’ – and becoming a ‘betrayal-anticlient’ as a result.) [This represents the ‘completion for self’ stage above, and the need to continue through to the ‘completion for customer’ stage.]

- Once both parties have achieved satisfaction relative to each other, do they then confirm that the overall end-results also fully align with the vision and values of the overall shared-enterprise? Failure to test for this risks creating a business – such as in much of the current ‘wealth-management industry’ – where providers and clients are (usually) happy with their respective services and service-relationships, but other stakeholders in the overall shared-enterprise feel increasingly betrayed: deep dissatisfaction here can eventually destroy an organisation’s (or even entire industry’s) ‘social licence to operate’. [This represents the ‘completion for all’ stage above.]

Yeah, I know: all of this has been way too long (as usual…). But the core takeaways would be these:

- Revenues and costs may occur in many different forms of value, not all of which should – or even can – be converted to monetary form. (To put it the other way round, money is often a very poor or even fundamentally-invalid proxy for many if not most forms of value: under no circumstance should money be allowed to be used as a proxy for all forms of value in an enterprise context.)

- The definition of ‘value’ ultimately arises from the vision and values of the shared-enterprise. The shared-enterprise is not the same as the organisation itself, and is not under the organisation’s control.

- Creating and maintaining reputation, trust, relations, respect, attention and conversation all incur real costs. These costs are typically referred to in business as ‘cost of acquisition‘ and ‘cost of retention‘. Note again that these costs often cannot be measured meaningfully in monetary terms.

- Costs of acquisition are typically (much) higher than costs of retention. In any context where repeated service-delivery is likely and desirable, it is therefore in a organisation’s (and customer’s) interest to expend the costs of retention in order to avoid the higher costs of re-acquisition.

- Failure to maintain reputation, trust, relations, respect, attention and conversation can lead either to significant ‘costs of de-acquisition‘. If a customer simply becomes a non-client, the de-acquisition costs represent a combination of opportunity-cost (loss of future business) and re-acquisition cost (same or higher costs as for initial acquisition. If either party – or any party – becomes an active anticlient of another party, the risks of the costs becoming real steadily increase over time, often in the form of supposedly-‘unpredictable’ kurtosis-risks.

Anyway, I’ll stop there for now: hope it’s useful for someone?

Leave a Reply