I’m sorry, but I just can’t afford it

Pray let me introduce you to a bleak, blunt fact of the futurist’s working-life:

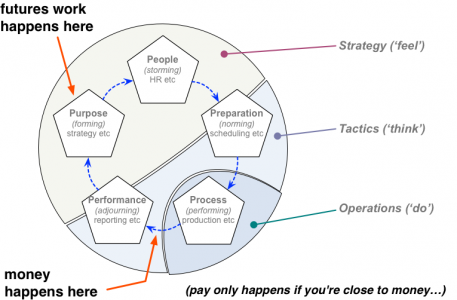

…where futurists work ain’t where the money is.

In this so-called ‘economy’, where money drives everything and short-termism rules the roost, there’s almost no way to make living as a futurist, in developing the understandings and tools and techniques that will be needed for the future.

But if the futures-work doesn’t happen, then neither does the future: it stops dead before it even has a chance to get started.

So here’s the dilemma: someone has to do that work, otherwise the future isn’t going to happen. But somehow they also have to find a way to get paid, otherwise in this, yes, definitely-insane economy, they’re not going to be able to make any kind of living, and thence won’t be able to do the work.

That pretty much describes my personal situation for the past seven years.

I’ve proved my point, and my competence in the futures for enterprise-architectures and the like: pretty much everything that, seven years ago, I’d insisted was essential for enterprise-architecture, is indeed now slowly being taken up. A fair few of the tools I’ve developed in the meantime – the tools that, yes, will be needed for the next stage of whatever enterprise-architecture becomes – are likewise indeed slowly being taken up.

But the keyword there, unfortunately, is ‘slowly‘: it’s all happening very very slowly, with a gap of maybe five to ten years between when the futures-work happens, versus when someone starts making serious money out of it. And very, very few people have paid anything towards helping that work happen – because, yes, futures-work is not where the money is, and most people still don’t realise that it doesn’t ‘just happen’, it’s very real work, and has to be paid for somehow.

There are a fair few people who do ‘near-futures’ work, six months or so ahead of the market: that’s the nominal value-proposition of many of the big-consultancies, for example. I’m one of the very few whose work is primarily at the equally-essential longer time-horizons. Which, again, means that I’m that much further away from the money.

Looking around, seems that just about everyone else in ‘the trade’ who does any kind of far-futures work does it only as part of their other paid-work: it’s a kind of sideline, not their main work. Most if not all of the other people I see at conferences and the like are fully paid-for, either by their employer, or as a paid presenter, or both. And it seems that just about everyone assumes the same applies to me: that someone else has already paid for my work, and that it’s therefore ‘free’.

Which, unfortunately for me, they haven’t, and it isn’t.

To be blunt, what I do is also damned hard work: few people seem to have any grasp at all just how hard it really is. It’s not just the sheer effort of trying to think things through and sense out suitable options for a viable future; it’s also the emotional work of dealing with people who seem to delight in trashing every scrap of it, ceaselessly, because they don’t understand it and can’t be bothered to understand it and reject it outright because it isn’t what they already think know about the past. Sigh…

A futurist’s work consists of dealing with relentless and often personally-intense dilemmas, such as:

- closely focused on the present, and the future, and the past, all at the same time

- constantly open to new possibilities, yet simultaneously applying strict discipline and rigour

- emotionally wide-open, to sense out the subtle undercurrents, yet maintain a skin thicker than rhino-hide to cope with all the insults and abuse

And, to again be blunt, those dilemmas in themselves create other kinds of costs that need to be factored into the overall cost-equation: constant self-doubt takes a serious toll, for example, whilst severe depression, risk of burn-out, and an intense, relentless sense of loneliness and isolation are routine occupational hazards here.

So, no, folks, I don’t just sit on my backside and pontificate: everything I do comes out of damned hard work, in many, many different forms. And for the past seven years I’ve worked flat-out, trying to render something usable out of the fragmented, inchoate, incoherent, seriously-dysfunctional mess that currently passes for ‘enterprise’-architecture. But this is where it gets hard…

All of that work has been paid for – if that’s the right term – almost entirely out of my own pocket. This has been my full-time job for seven very long years: and to do this job properly, I have had no space for any other source of work or source of income. And the income just hasn’t been there: at best, low-end of four-figures gross-income, per year, for seven years. Yeah, just think about that for a while: just how long would you be able last on almost no income? Watching the savings dwindle away to nothing, at an additional opportunity-cost of well over half a million at today’s pay-rates for enterprise-architects, just so that someone else can make a serious fortune a few years down the track? Just finding ways to deal with that fact alone has made the work much, much harder, in every possible way.

And that has had huge, huge impacts at a personal level, in every form of cost. To give just one example, I think it’s fair to say that I’ve been one of the most active thought-leaders in enterprise-architecture, for many years now: but of the ten conferences I’ve been asked to speak at this year, not one has actually paid anything for me to do so, or provided any kind of cover for the typically three to five days it takes prepare and present a reasonable-quality session; and only two out of the ten have been polite enough, or respectful enough, to realise that I’m doing a heck of a lot of work on their behalf, and have actually offered to at least pay my expenses for travel and accommodation. This year, as in every other year for the past seven years, I’ve given a heck of a lot of direct, deeply-researched in-person help to a lot of people in enterprise-architecture, some of them very-highly-paid professionals; but other than one very-supportive colleague in Latin America, no-one has thought to pay even a single cent towards covering my very real costs in doing so. And at the same time, I see case after case of people doing very poor-quality ‘EA’ work yet being paid very high sums for not-doing it. That fact galls, to say the least: it hurts every damn day.

So here’s the news, folks: I’m sorry, but I just can’t afford to do this any more. Not this way.

If you don’t value any of my work in way, well, that’s fine, that’s your choice – my fault for being so stupid as to waste a serious slice of my life and virtually all of my savings on something that no-one else wanted anyway.

Yet several people have said that they do value my work, that they do want me to keep on going on this, continuing to find ways to make some form of real enterprise-architecture or equivalent viable for the future. But reality is that I just can’t do it any more – not this way.

(Nor, by the way, can any other futurist afford to keep on going this way – I’m by no means the only one in this futurists-don’t-get-paid boat. It’s hard for all of us…)

Right here, right now, for me personally, this is crunch-time: I’ve no more reserves of any kind – financial, emotional or otherwise – so I either have to find some kind of alternate way to make this work, or else close the whole thing down, for good.

Hence, if you do want me to be able to continue in this, then I’m going to need serious help from you – or from someone, at any rate.

I’m going to need help in finding a business-model that actually works, and that would help me recoup at least some of the enormous costs of the past few years.

I’m going to need help in bringing my work down to a more concrete, practicable, directly-usable form, so as to cut down the time-gap between the raw futures-work of initial development versus the point of practical application and monetisation.

I’m going to need help in quite a lot of technical spaces – graphics, for one, and app-development, for another, to deliver the kind of toolset that would actually be of some real use in enterprise-architectures and much, much more.

And I’ll also admit I’m going to need help in dealing with the sheer emotional and other pressures of doing this kind of work – because, make no mistake, that part of the work is probably the hardest of all.

That’s it for now, I guess.

Over to you.

Well I am, as you say, surprised. From the way you wrote in Real Enterprise Architecture (which was interesting and useful to me, and finally brought me here today) it seemed that you brought a lot of experience from working, and working pays.

FWIW, I do things the other way around; I mainly work (and study) and part time teach the people around me with the things that I know that they don’t. This way I get paid for what I know, and I spend my time working at the grim, hard-push, treacle-like environments of actually changing peoples’ minds. I highly recommend it, not least because you get paid! By publishing Good Works (or in my case by talking to all and sundry 🙂 you increase your reputation and, with it, your saleability and so your rates.

The problem with getting out of the ‘doing’ (as I found when I went academic for a while, and you seem to be finding) is that slowly everyone else catches up with you, leaving you back in the mob rather than out front.

So absolutely go and do some high quality EA work and get paid very high sums. And then tell us about what you learned from it, and charge for it whenever you can. And then get back to paid work. It means the frameworks you (and some of the rest of us) are working on won’t develop as fast, but it also means they won’t go solid and stale.

Thanks, Martin. There is, unfortunately, a huge catch in relation to your advice, and it’s about this: “go and do some high quality EA work”.

I’d love to: but the blunt reality is that there is no such work in this benighted country. Not that I would understand as ‘enterprise-architecture’, anyway, and none for which my skills and experience are an adequate enough fit to get past the mindless box-ticking gatekeepers that mostly pass for ‘recruiters’ in this country.

Sure, there’s plenty of what claims to be ‘enterprise-architecture’ here: I went through many hundreds of such job-descriptions when I moved back here seven years ago. The vast bulk of it, though, is detail-level IT – Java and suchlike – exactly as I described in my ‘personal background’ post the other day. The small part that remains is almost entirely mid-range IT for banks and so-called ‘finance’: my IT skills are way out of date for that kind of work, and – no offence – I prefer not to work for thieves if I can possibly avoid it. In seven years in this drizzerable greyness of country I have yet to see any advertised role that even begins to resemble the necessary scope and scale of a true enterprise-architecture. The TOGAF-style term-hijack is so complete here that no-one can even begin to see what’s actually needed to make an enterprise work: instead, all we get is IT, IT and more IT, none of which ever seems to deliver what’s actually needed for the requirement, but somehow does seem to need endless tending at ever-increasing cost. Surprise, surprise… :very-bleak-wry-grin:

The other catch, as is probably all too evident by now, is that my so-called ‘soft-skills’ are nowhere up to the job of coping with the level of inanity, childishness and flat-out idiocy that seems utterly endemic in just about every organisation I’ve had to deal with – especially in the so-called ‘higher’ levels of the hierarchies, just below the occasionally-competent people who run the show from the top. At my age I just don’t have the patience to deal with that kind of crap: sorry…

To me, Britain in general – though possibly only middle-England in particular – is now sadly best dismissed as a write-off: with just one ‘industry’ left, and that seemingly based primarily on fudging and fraud, it doesn’t hold out much hope for the future. For family reasons I’m still somewhat stuck here at present, which does make things somewhat difficult in practice – but I’m close to cracking either way, so in some ways it doesn’t make much difference. What I’m working on right now is finding out which country – if any – offers any possibility to do the work that I need to do, and still somehow find a way in which I can survive in doing so. The most obvious option would be to return to Australia, but with a new right-wing government hell-bent on denying reality, and instead propping up the suicide-pact of the mining-industry for as long as possible, that doesn’t hold that much charm either.

In short, to quote Dave Winer, “It’s worse than it appears”. A lot worse, actually.

So thanks again for your well-meant advice. I’m just having rather a lot of difficulty finding any way to put it into practice, that’s all.

Hmmm I think part of the reason you’re gloomy about all this is that you’re not seeing industry from the inside – your view has been shaped by seven years of reading sensationalist newspaper stories about fraud and thieves and how all is lost, etc.

I recently moved to what might be loosely called ‘corporate consultancy’, bringing with me technical expertise and inclination, but where the job involves organising organisations including IT, rather than an IT view of organisations. So far it’s been surprisingly pleasant, even if I do find myself turning into what I used to despise when I was an engineer – because now I can see what I didn’t then. This is proper enterprise engineering, and you can see the benefits to the company and its staff, so quite rewarding if you’re after more than just cash.

A friend of mine once said that building and engineering metaphors were not good for information systems; gardening metaphors are much more appropriate. Things are messy and only some things are well understood, and some things are well understood but not useful, you have to work just to keep things in a particular state, you have a range of tools of which some are customised to a particular job, only some things transfer well between gardens, etc etc.

You should not have any patience for people who have no patience 🙂 including yourself

Martin: “your view has been shaped by seven years of reading sensationalist newspaper stories about fraud and thieves and how all is lost, etc”

Uh… no, not quite… More accurately, it’s been formed by about fifty years of very careful in-person observation and study with and for and around people who do know what they’re talking about, and, yes, business- gigs too, across a couple of dozen industries (including your own defence-industry) in something like a dozen different countries so far.

@Martin: “building and engineering metaphors were not good for information systems; gardening metaphors are much more appropriate. Things are messy and only some things are well understood, and some things are well understood but not useful”

I, uh, presume you do in fact know that I’m one of the people who’s most pushed exactly that point in enterprise-architectures, yes?

In short – and yeah, short as in ‘short-tempered’ is also somewhat coming up here – I’d really appreciate if you were somewhat less patronising and considered the possibility that I do actually have some solid reasons for saying what I do?

Grrr…

Heh, well you made some very sweeping statements about the awful state of UK industry that are just not visible from the several places I’ve been looking at it for the last ten years, nor are they reflected in the improving productivity and capability.

The engineering vs gardening comment was there mostly because *I* had talked about engineering the organisation. I thought you might like the gardening metaphor as it seemed to reflect the limited amount of your stuff that I’ve read.

I thought this was an excellent post. It illustrates how “skills” are not paid for and only ideas that are two steps away from the majority is hired for pay.

Your contributions have been enlightening. Unfortunately, not by those with budgets. You are way ahead of where corporations are thinking.

Even entrepreneurs are thinking small. They look for a problem and come up with a single solution. Complexity on a much smaller scale.

What you do is much broader than a single problem. You notice cultural shifts and prepare organizations for it. Unfortunately, organizations are usually behind.

I have no advice at this moment to provide. I hope my acknowledgement of your plight gives you some strength to take a step back and see something to do next.

Many thanks, Pat. I’ll do what I can, as and how I can – nothing much more I can say than that, I guess.

Dear Tom,

I can understand the situation you’re in. It sounds incredibly similar to my PhD – 7 years of almost total isolation and toil in an obscure area of astrophysics which no one much cared for. They gave me £6000 a year for the first three years, and nothing at all for the last four, in which I eked out a living by tutoring kids in maths and physics. Unlike you, I hadn’t worked in a “proper job” before the PhD, and so didn’t have money to start with, and so went without holidays, haircuts and new clothes for years at a time.

The problem with your work, and the problem with my academic research, is that it is so far removed from reality, that it does not attract money. Normal people do not pay for it, since they derive little value from it. It is only the application of our theories that attracts money.

I urge you not to give up on your work – in many ways, you are the best of us – you make EA human. But for your own sake, you need to find a balance between the abstract and the real. Even futurists have to eat, and since EA pays so well, even a short contract would shake out the cobwebs, restore your confidence, and get you back on your feet again.

All the best, and good luck,

M

Hi Tom,

this guy has resolved the type of problem you describe in this blog. Check it out. Also, your work looks great, keep it up 🙂

http://www.mattchurch.com/thoughtleaders/