Managers, leaders and hierarchies

Is ‘manager’ the same as ‘leader’? Are leaders always managers? And are hierarchies – and, in particular, classic management-hierarchies – always a natural, necessary and unavoidable fact of (larger) enterprises?

These questions came up for me whilst reading three articles on LinkedIn by Stanford professor Bob Sutton, of ‘The No Asshole Rule‘ fame:

- Management vs. Leadership: A Dangerous But Accurate Distinction

- Real Heroes at Pixar: When Leaders Serve as Human Shields

- Hierarchy is Good. Hierarchy is Essential. And Less Isn’t Always Better

It also struck me whilst reading there that Enterprise Canvas and Five Elements might provide some useful ways to highlight some of the key distinctions in those articles. Hence what follows…

Managers

What does a manager actually do? There is, of course, a vast literature on this, but there are a few themes that I would particularly pick out for this purpose here:

- adapt broader organisational strategy, tactics and operations to the context of the specific services in scope (the manager’s ‘reports’)

- acquire and distribute resources within the services in scope, including any ‘child’-services (in a service-decomposition hierarchy)

- coordinate (or assist in coordination of) the run-time operation of the services in scope, including any ‘child’-services (‘line-management’)

- acquire, collate and aggregate information, and pass elsewhere as required (e.g. ‘report’ to own-manager)

- provide assistance for coordination with other ‘sibling’-services and/or service-providers and service-consumers

- provide assistance for whole-of-organisation alignment and compliance to enterprise values (quality, safety, security, environment etc)

- manage and balance value-flows to and from the service’s investors and beneficiaries (if any)

(One theme I deliberately haven’t included above is the people-issues – skills-building, arbitration, recruitment, derecruitment and so on. This is mainly because I regard it more as a specific type of ‘leader’ role, rather than management per se.)

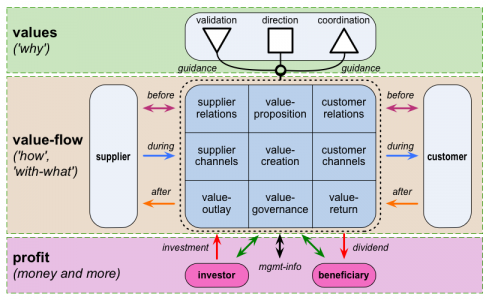

That set of themes fits exactly with the ‘within-the-service’ and ‘beyond-the-service’ relationships mapped out in Enterprise Canvas:

Although it’s recursive – which is where we come back to hierarchies later – classic ‘management’ occurs in two main places in Enterprise Canvas:

- value-governance sub-services within the service – aka ‘line-management’

- direction guidance-services from beyond the service – aka ‘staff-management’

Following Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM) – on which Enterprise Canvas is in part based – the ‘direction-services’ can be further split into three parts:

- identity and purpose (VSM system-5)

- ‘outside-and-future’ (VSM system-4)

- ‘planning and control’ (VSM system-3)

In essence, ‘strategy-management’ is derived from the links between system-5 and system-4; ‘tactics-management’ are derived from the links between system-4 and system-3; and ‘operations-management’ derived from the links between system-3 and the ‘value-governance’ sub-services within the service – which themselves in turn also represent (some of) the ‘direction-services’ for the next level ‘down’ in the recursion of service-decomposition.

In VSM, coordination between services (system-2) and validation of enterprise-wide qualitative themes (system-3star – only as ‘random audit’ in VSM, fully generalised in Enterprise Canvas) are not included in or subsumed into the ‘direction-services’ roles: they are separate and distinct. The reasons for this separation of responsibilities would be clear from observation of real-world practice: coordination is primarily ‘horizontal’, whereas ‘direction’ is primarily ‘vertical’; and validation is necessarily pervasive, hence must apply to management as much as to everyone else – and hence cannot be under their control.

The service itself is an instance of VSM system-1. Which, as per the fractal nature of VSM, also incorporates its own specific instances of all of the other systems (2, 3star, 3, 4, 5) – in other words, its own context-specific instances of management-direction, coordination, validation and further ‘line-management’.

Note also the potential investor and beneficiary relationships which – where they exist – would typically be managed via the service’s own ‘value-governance’ sub-services (line-management at the respective level – which may in practice be viewed as a ‘staff’ function, because it typically occurs at the ‘higher’ recursions of the structure). These are not described in VSM, but are crucial in explaining one of the core reasons for organisational dysfunction and breakdown in Taylorism and the like.

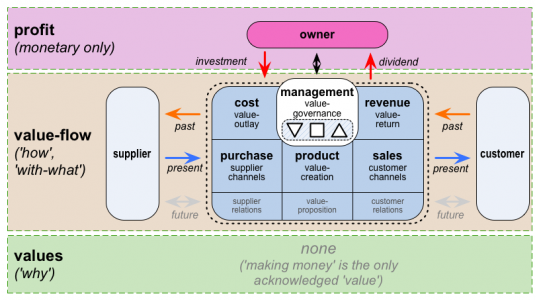

In a Taylorist model of the organisation and its management, the VSM-type structure of the Enterprise Canvas is turned completely upside-down:

There are two very important outcomes from this inversion:

- the wishes of the small subset of stakeholders who self-select as ‘the owners’ become the purported ‘purpose’ of the organisation and of its relationships with the extended shared-enterprise, and are reframed also to determine the purported values of that extended-enterprise

- all of the ‘guidance-services – direction, coordination and validation – are subsumed into the service-specific value-governance sub-service

This has huge consequences:

- in a commercial context, the organisation is reframed as ‘a machine for making money’, with all other enterprise-values framed as of subordinate priority to that one all-encompassing goal – leading to directly to ethics-problems, environmental-problems, quality-problems and many other large-scale dysfunctions

- with coordination subsumed into vertical-hierarchy ‘management’, there is no means to manage ‘horizontal’ concerns, other than by forcing both parties in a horizontal ‘sibling’-type link ‘inside’ the respective branch of the hierarchy, or by pushing the coordination ‘up’ the hierarchy-tree – leading directly to hierarchy-traversal bottlenecks, ‘control’-battles and turf-wars

- with validation subsumed into and under the control of ‘management’, there is no means to ensure validation of management itself – directly leaving it wide-open to corruption and other ethics-violations

- with management in full control of value-return, yet also with control of what should have been the mechanisms for overall validation, there is no means to manage management itself – leading directly to high risk of embezzlement, self-assigned salaries and bonuses, and unresolvable clashes with ‘the owners’ (and also, if indirectly, with ‘the workers’ and other stakeholders)

- in the same way that the values of the entire organisation are deemed subservient to ‘the owners’, all other services are deemed subservient to ‘the management’ – leaving the organisation as a whole completely reliant on the quality (if any) of its ‘management’

- in the Taylorist inversion, many of the communication-paths outlined in Enterprise Canvas end up facing ‘the wrong way’ – leading directly to lack of distribution of sensemaking and decision-making, and thus to inevitable cognitive-overload amongst ‘managers’

Evidence of these direct consequences of the Taylorist-style inversion can be seen everywhere in business…

To put it at its simplest:

- a management-structure based on VSM or Enterprise Canvas – with distributed sensemaking and decision-making, autonomous or semi-autonomous coordination and validation, and with its hierarchy derived from context-driven service-decomposition – is likely to be stable, dynamically-reconfigurable, ‘viable’ in the VSM sense, and supportive of and through the whole organisation

- a management-structure based on the Taylorist-style inversion will, almost inevitably, become highly dysfunctional and ‘toxic’, as above

Hence the problem isn’t management itself: instead, much as Deming warned, the management-system is the key problem-area, and thus the area in most need of attention.

Note, though, that this still doesn’t address the point about ‘management versus leadership’ – which is what we need to look at next.

Leaders

What is leadership?

The simplest answer, of course, is that leadership leads. But where? In what way? How? Why? For what purpose? There’s a lot of confusion around all of this…

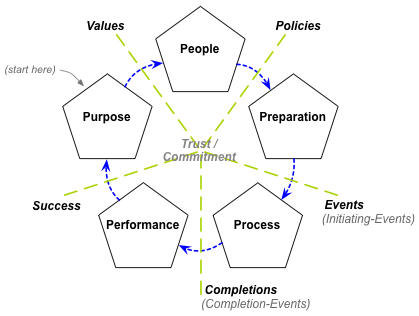

To simplify it right down, both for the business-context and for elsewhere, I’d suggest we use another one of my context-space mapping frames, namely Five Elements:

I won’t go into the detail of the model here: suffice it to say that it’s a kind of expanded version of the Bruce Tuckman ‘Group Dynamics‘ project-lifecycle model that I’d think most people would know – ‘forming’, ‘storming’, ‘norming’ and so on – but made fully-recursive and scaled-up and re-mapped to the activities of the enterprise as a whole.

(There are some interesting potential cross-maps between Five Elements and the VSM ‘systems’, but I’ll leave that for another post – or as ‘an exercise for the reader’, perhaps? 🙂 )

The point I want to show here is that there are three distinct types of leadership indicated in that framework:

- leadership within a domain of activity – Purpose (‘forming’), People (‘storming’) and so on

- leadership between domains of activity – from Purpose to People (i.e. ‘Values’), and so on

- leadership of leadership for the enterprise as a whole – ‘holding the centre’ (i.e. ‘Trust / Commitment’) and suchlike

For ‘leadership-within’, the leader is typically a specialist in that domain. The leadership consists primarily of helping others build their skills and expertise in that domain.

For ‘leadership-between’, by definition the leader is not a specialist within one domain, but a generalist who knows how to help people through the cognitive-dissonance of switching from one domain to another. Another key task here is to get the leader of the previous domain to stop and let go, so that the move on towards the next domain becomes possible. And as with ‘leadership-within’, there’s also a set of tasks around helping others develop their skills in this ‘between-domain’ type of leadership.

For ‘holding-the-centre leadership’, the challenge is around keeping the balance: ‘leadership-within’ leaders will naturally tend to want people to stay in their own domain, ‘leadership-between’ leaders will naturally want to keep people moving on, and everyone thinks that their own domain or between-space is the most important of all and should be the centre of everyone-else’s attention – so it’ll be clear that there’d be an inherent tension there, right around the cycle…

By contrast, in a Taylorist-style model, a ‘leader’ is all but defined as ‘someone who tells others what to do’. In effect, the supposed ‘leader’ typically ‘leads from the rear: leadership by demand’ rather than ‘leadership by example’. Others ‘follow’ only in the sense that they follow the instructions or enact the demands: they – not the ‘leader’ – take on all the responsibility for the actual lead into ‘unknown territory’ and suchlike. And are landed with all of the blame if anything goes wrong, too…

In the same way, another theme that we’re likely to see from real leaders – and that we’re very unlikely to see from Taylorist-type ‘leaders’ – is a willingness to take risks on behalf of others: again, a real ‘lead by example’, rather than ‘lead from the rear’. Bob Sutton gives an extremely good example of this in his ‘Real Heroes at Pixar’ post linked above.

Managers as leaders, leaders as managers

Using Five Element again as an example, there are also quite different modes of leadership around that cycle as well, which we could summarise as feel, think and do:

In the kind of organisation indicated by Enterprise Canvas, we’ll see leaders who exemplify each of these strands: leaders who focus on ‘the feel of the future’, or on human emotions and concerns; leaders who focus on planning, analysis and review; and leaders who focus on action, on getting things done. In some ways this summarises what should be a balanced ‘C-suite’, revolving around the centre-point nominally represented by the CEO:

- Purpose: CSO (Chief Strategy Officer), CInO (Chief Innovation Officer)

- People: CDO (Chief Development Officer), CPO (Chief Personnel Officer)

- Preparation: CIO (Chief Information Officer), CCO (Chief Change Officer)

- Process: COO (Chief Operations Officer), CTO (Chief Technology Officer)

- Performance: CFO (Chief Finance Officer), CLO (Chief Legal Officer)

Yet if we take a Taylorist view that “managers think, workers do”, suggests that in a Taylorist-type organisation with ‘think’-oriented managers in the ascendant, it’s probable that only those involved in ‘think’-type work would be considered as ‘leaders’. Which is exactly what we see in practice: ‘leadership’ is taken to be synonymous with ‘management’, either with the near-future focus of the Preparation domain (CIO, CCO), or the past-orientation of the Performance domain (CFO, CLO) – and nothing else as leadership at all.

Under a Taylorist-type model, what we often see in would-be ‘leadership-development programmes’ is an active embodiment of the ‘all leaders are managers; management is leadership’ myth. To use the Five Element model further above, anyone who demonstrates some activity or aptitude for leadership in any of those eleven forms summarised above is taken out of their existing work, and groomed and re-trained to be a manager. This works well enough for the forms of leadership that do align with the ‘think’ modes of the Five Elements cycle (Preparation and Performance), but can often be disastrous for the others (Purpose, People, Process, and the ‘between’-leader and ‘holding-the centre’ modes), actually destroying the potential for leadership in those domains.

To give a first-hand example of this, some years ago a friend of mine applied for a front-line teaching post at a middle-school in a fairly rough area of London. He was well-qualified to do it, no question about that, with a couple of decades of much-praised experience as a teacher in that subject. But the sticking-point that worried his interviewers most was that his present job was not front-line in the classroom, but head of department – and in one of the most prestigious schools in the country. What was wrong? they asked him. What had he done wrong? After being promoted that far, why would he take such a huge demotion?

His answer was simple: “I’m a teacher, not an administrator”, he said. “I want to teach. I belong in a classroom, not behind a desk – no matter how fancy the brass plate they put on my door.” In short, he was a real leader, an educator in its literal sense of ‘out-leading’: but they’d forced him to take on a form of ‘leadership’ that didn’t match up with his own nature at all. And he’d hated it: he wanted, urgently, and with all his heart, to get back to the form of leadership that he’d made into his life’s work. (I’m glad to say that, yes, he did indeed get the job – and still doing it well, from what I last heard.)

So that’s perhaps one of the most important and yet most common of the Taylorist traps that we see in organisations today: a failure to understand that whilst managers may well be leaders, not every leader is a manager – or should be.

Hierarchies and ‘management structures’

Smaller organisations may be able to go ‘manager-less’, but as scale increases, the need for some kind of resource-coordinator role, and the other ‘guidance’ functions indicated in Enterprise Canvas, become more and more prevalent. Hence, managers, and management – which in turn implies some kind of ‘management-structure’.

And yes, the most common management-structure that we’ll see is some form of hierarchy. If Bob Sutton is correct, then hierarchies are an almost inevitable – and perhaps even essential – feature of management, particularly for larger organisations. Yet hierarchies can be highly functional or highly dysfunctional – the presence of hierarchy itself doesn’t tell us which it will be. The crucial concern, then, is less about whether the hierarchy does or does not exist, and more about whether a hierarchy genuinely does support the needs of the organisation and enterprise, or whether it puts the whole enterprise at risk. In the Taylorist-style concept of hierarchy, the latter is more likely… but it can be prevented.

The usual way that hierarchies are portrayed in business is as ‘vertical’ branching-tree structure: branches and more branches and yet more branches devolving ‘downward’ from a single inverse root – such as in the infamous ‘org-chart’. Yet if we think about it – especially in context of something like Enterprise Canvas modelling, where the links of the hierarchy are merely support-relationships – there’s no reason whatsoever to assume that the branch-structure must always be vertical and top-down: it could just as easily be sideways-on or bottom-up instead. So why is it so rare that we see either of those other views portrayed – especially for something like an ‘org-chart’, which technically represents relationships between support-functions of an organisation?

The answer, once again, is Taylorism, and, behind it, the feudal cultures from which it rose. Yet interestingly, Taylorism and its ilk actually manage to be worse than feudalism – at least in the sense of being even more inherently-dysfunctional, inefficient, ineffective and problem-prone. Feudalism asserts two-way relationships of mutual-responsibility, with the overlord responsible to the vassal as much as the vassal is to the overlord. By contrast, Taylorism inhabits a world of one-way responsibilities: supposedly-omniscient ‘bosses’ place demands upon their presumed-robotic vassals, but have little to no responsibilities to those vassals in return. Orders go ‘down’ the hierarchy-tree, and results-information comes back up – but other than that, there’s no mechanism available, or allowed, to discuss the contextuality or anything else about those commands. The result is a world immortalised by the inanities of Dilbert’s ‘PHB‘ (Pointy-Haired Boss):

… notable for his micromanagement, gross incompetence and unawareness of his surroundings, yet somehow retains power in the workplace.

The list of dysfunctions probable in this type of hierarchy is long, disturbing, and sometimes downright scary. They include:

- positions ‘above’ in the hierarchy provide unchallengeable ‘high-status’, in the sense used in improv-theatre

- since promotion ‘upward’ is often the only available mechanism for reward or recognition of service, people are (as earlier above) often moved to managerial roles for which are neither suited nor trained – a common driver for the Peter Principle

- in some contexts, promotion is the only way to get rid of someone who is incompetent – another common driver for the Peter Principle

- conversely, someone who is competent may be trapped in a ‘low-level’ job, simply because they’re the only one who can do the work – an inverse corollary for the Peter Principle

- the boss / vassal relationship provides a classic codependent-pair, in which both parties can evade responsibility for actions/inactions and their consequences, by blaming the other

- the boss retains the exclusive ‘right’ to sanction or punish vassals – the concept of ‘insubordination’ is not counterbalanced by a matching concept of ‘insuperordination‘ – enabling bullying to run rampant in many work-cultures (as documented by Bob Sutton in ‘The No Asshole Rule‘)

- the lack of checks and balances enables rampant paediarchy (‘rule by, for and on behalf of the childish’ – a concept I’ll expand on in an upcoming post)

- fear of sanctions (whether unfair or ‘fair’) incites vassals to ‘launder’ or ‘sugar-coat’ performance-figures and bad-news in general, resulting in increasing distortions of information as it moves ‘up’ the hierarchy-tree – placing organisational sensemaking and decision-making at risk

However, hierarchies can be functional and successful, if appropriate checks and balances are in place to counter all of these ‘natural tendencies’. In essence, the dysfunctions arise from the neo-feudal overlay – not from the nature of hierarchy itself.

In his ‘Hierarchy is good’ post, Bob Sutton argues that “organisations and people need hierarchy”. One of the reasons that Sutton gives is that clarity on roles and relationships made explicit by a hierarchy-structure can itself reduce some of the ‘pecking-order’ dysfunctions described above. From what I’ve seen in practice, that’s probably true – particularly where there are already low levels of mutual-trust, where ‘status-games’ tend to run rampant unless checks are in place to mitigate against them. It’s also important to keep the structural relationships of the hierarchy separate from the interpersonal respect-relationships, as Sutton indicates in a quote in his post:

“…never confuse the hierarchy that you need for managing complexity with the respect that people deserve. [T]hat’s where a lot of organizations go off track, confusing respect and hierarchy, and thinking that low on hierarchy means low respect; high on the hierarchy means high respect. So hierarchy is a necessary evil of managing complexity, but it in no way has anything to do with respect that is owed an individual.”

Hierarchy-structures can also be used in combination with other relationship-structures. One the things that first got me interested in this whole field was an article I read in Scientific American, nigh on fifty years ago, that talked about management-structures in high-stress environments: two of the examples they gave were electricity- power-distribution, and flight-deck on an aircraft-carrier. All of the examples had arrived independently at a hybrid-structure that I would now describe as ‘hierarchy-flat’.

They all had strict, explicit systems of ranks and the like, in part to clarify reporting-relationships and level of overview, but also to clarify respective responsibilities, autonomy and scopes of action. The ‘downward’ paths of the hierarchy provided fast channels for distribution of information and guidance, much as per Enterprise Canvas ‘layering’; and also return-paths for aggregation of results-information. Yet the crucial understanding was that, whilst the hierarchy’s return-paths were appropriate for ‘normal’ conditions, they could well be far too slow for emergency-conditions. Hence the hierarchy was also balanced by an explicit ‘flat’-structure – an ‘any-to-any’ communication path, in which anyone could pass emergency-information to anyone else. The safety of the ship, for example, was everyone’s responsibility: hence even the ‘lowest’ junior-sailor might need to warn the admiral, direct, if she perceived a risk to the ship – and needed full authority to do so, at any time, regardless of rank. Interestingly, all of these organisations maintained cultural rituals to reinforce both of these themes, as a balanced pair: the ranking-structures of the hierarchy, and the ‘everyone is equal’ of the ‘flat’-model.

Practical implications for enterprise-architecture

What do we do about this? It depends on what’s needed, of course. And for some of this, there are likely to be huge challenges and political-repercussions from this kind of work – especially from the middle-management layers in larger organisations – so don’t even think of trying to do it without full overt support at executive-level…

That said, there’s quite a few themes that we can work with, just from what’s described above.

First, in relation to the ‘managers‘ theme, identify what kind of ‘management’ you’d want managers to do – what outcomes are needed, what information-flows, what kind of support they would provide, and so on. For this, the Enterprise Canvas roles and relationships can provide a pretty good guide:

- direction: big-picture, identity, purpose and strategy (VSM system-5)

- direction: ‘outside and future’, business-intelligence, context for tactics (VSM system-4)

- direction: ‘inside and now’, staff-management support for run-time operations (VSM system-3)

- coordination: strategic change (VSM system-2 to system-5/4)

- coordination: tactical change (VSM system-2 to system-4/3)

- coordination: operational coordination (VSM system-2 to system 3/1)

- validation: create awareness of importance of value (extended VSM system-3*)

- validation: build capability to enact value (extended VSM system 3*)

- validation: audit action on value (VSM system-3*)

- value-proposition: line-management for service purpose and future (VSM system 5/4 within system-1)

- value-creation: line-management for operations (VSM system-3/2/3* within system-1)

- value-governance: line-management for performance-review (VSM system-3 within system-1)

- (also) support-management for ‘child’-services (all VSM systems with system-1)

Following the logic of the Viable System Model, all of those forms of guidance and management need to be in place if the service is to be viable, especially over the longer-term. Hence, in effect, that set of bullet-points just above provides a basic checklist for completeness of required inter- and intra-service relationships, at least from the perspective of management.

Also verify that they do conform to and support the logic of Enterprise Canvas in terms of what is and isn’t subsumed into the ‘management’-functions. In many organisations, there will be a lot of pressures to place the stockholders as the first priority of the organisation: resist those pressures at all costs – within the architecture, at least – otherwise you will automatically end up with a dysfunctional Taylorist-type management-structure.

With regard to the ‘leadership‘ theme, identify what forms of leadership are required to keep the organisation moving along, and in balance. For this, the Five Element model above could provide an overview-checklist, though in practice it would almost certainly to be brought down out of the generic and abstract of that model, and more into line with the specific needs of the organisation. As a minimum, ensure that you cover all three of those major categories of leadership:

- leaders who help things happen within a domain

- leaders who help things move onward between domains

- leaders who help to ‘hold the centre‘, the balance of the whole

One thing we can be sure of, though, is that that set of required leader-types will always be broader than the myopic ‘the managers are the leaders’ model inherent in Taylorism…

And with regard to the ‘which hierarchy?‘ question, use structural-orientation to mitigate the risks of dysfunctional-hierarchies. As indicated in Enterprise Canvas, inter-services management-type relationships will tend naturally to form into hierarchy-type tree-structures. However, as explained in the ‘Insuperordination’ post:

…top-down ‘command-and-control’ hierarchy is an overlay on top of a tree-structure that arises naturally from aggregator/resource-distributor relationships. The tree-structure provides a genuine service; the hierarchy, all too often, a genuine disservice. Don’t conflate the two structures: they’re not the same.

The way to separate them is that the tree-structure could be viewed in any orientation: top-down, bottom-up, sideways-in, centre-out – it’s all the same. But the [command-and-control] hierarchy is always described as top-down: it can’t be made to (seem to) make sense in any other way.

Hence, a simple test for the architecture and its concomitant design: apply a reframe, such that management-relationships are re-described as support-functions rather than command-functions – bottom-up, rather than top-down, explicitly negating any purported ‘rights’ to command-and-control. Doing so tends to surface any covert embedded-dysfunctionality, often very quickly indeed – another reason why you definitely need full executive-support before attempting to do this kind of architectural work…

Anyway, I’ll leave it at that for now – but I hope this yet-another-long-ramble has been useful to someone, perhaps?

Another great and yes, very useful post Tom. I’m kind of surprised not to see any other comments here.

Hard to single any one part out but I think I’m particularly struck by your handling of the hierarchy question. Very eloquent and objectively presented. I think it’s not useful to take a good/bad position on the topic outside of a clear context, although I’d admit to having been guilty of that in the past. I don’t accept that there is any scientific justification for the claim (not made by you of course) that hierarchies are essential for managing complexity. And what anyway do we mean by “managing” complexity? Seems pretty Taylorist to me. On the other hand an alternative option is equally unprovable, so the focus needs to be on the context. I think Ruth has influenced me here too.

So thanks again. I may come back with some additional observations later – based on my own experiences.

Many thanks for this, Stuart, and glad that the “handling of the hierarchy question” was useful. (Been having a bit of a day with someone dismissing some of my work as ‘profound garbage’, so this comes as a pleasant change! 🙂 )

And yeah, agree re “Ruth [Malan] has influenced me here too” – one of the most important thinkers / practitioners in our space, I’d say.

Will look forward to further comments – again, much-appreciated!