Efficient, effective, convenient?

Is convenience even more fundamental to an enterprise than either efficiency or effectiveness?

That’s the curve-ball that Nick Gall threw to me, in a comment on my earlier post ‘Efficient versus effective‘.

It’s quite a long comment (and, unfortunately, quite a long reply here…), so I’ll split it up into its paragraphs and reply to each in turn.

Before we start, I’d best warn that this might at first seem just another exercise in Tom’s Pernicketily Pedantic Precision – yet I think (hope?) that by the end of it you’ll see why being so pernickety and pedantic has its very real payoffs…

It recently occurred to me that there is a something even more fundamental than either effectiveness and efficiency. It is convenience.

More fundamental? More common, perhaps, yes; but inherently of higher-priority than either efficiency or effectiveness? I have very real doubts about this… as I’ll explain as we go along.

Likewise, convenient in what sense? And for whom? Those are definitely non-trivial questions…

Think about it. If something is sufficiently convenient for someone, she will sacrifice large amounts of efficiency and effectiveness for the sake of such convenience. That’s why we as individuals and as communities are so wasteful. Look at “conveniences” like fast food, disposable anything, even convenience stores.

Yeah, I do think about it, a lot. Which is exactly why it worries me, a lot…

And which is also why the questions “Convenient in what sense? for whom?” become extremely important – especially for an architecture of the enterprise.

Think about it in turn: if creating wastefulness is a core driver for the entire enterprise, just how long do you think that enterprise is going to last within a broader closed-ecosystem? Short answer is, yeah, it’ll poison itself at some point, or just plain run out of resources, through lack of efficiency. Which means that it’s also ineffective, because it can’t keep on going – it can’t continue its success. In that sense, convenience cannot and must not be assigned a higher priority than efficiency or, especially, effectiveness.

If the inefficiency and wastefulness are low enough such that other not-actually-acknowledged parts of the ecosystem are able to deal with the wastes and replenish the renewable-resources, it can perhaps seem like the system could continue forever. Reality is that it’s in fact dependent on those not-actually-acknowledged components in the enterprise’s broader-ecosystem – which introduces very real and very dangerous risks for the enterprise.

Since the advent of consumerism, yes, ‘convenience’ has become a very common element in business-models and in many so-called ‘value-propositions‘. Yet when the business-model depends on creating wastefulness – as in ‘planned-obsolescence‘ and suchlike – the resultant increasing system-stresses and decreasing system-efficiencies put not just the business-model but the entire ecosystem at risk. As can be seen all too easily at your local garbage-mountain…

In systems-terms, it’s merely one example of what I’ve termed the ‘quick-profit failure-cycle’:

It’s a short-cut version of the real business-cycle that’s seemingly very profitable in the short-term, but suddenly drives itself into the ground, often apparently ‘without warning’, when its inefficiencies finally catch up. The only people who really ‘win’ from such a cycle are the scavengers – and even will they drive themselves into oblivion when the whole ecosystem becomes too poisoned for its survival. This isn’t a human-specific pattern, by the way: it applies at every level of ecosystem, including those in which (in principle) no human is involved at all.

People generally aren’t all that interested in making their own lives more efficient or more effective. It’s typically managers who want the people they manage to be effective and efficient. People generally just want things to be easier for themselves, i.e., more convenient, even if it means being less efficient or effective.

I fully agree that that’s what people want (or perhaps have been taught to want, or incited to want, in a consumerism-based economics and a ‘rights’-based political-model – which is not necessarily the same as what they actually want…).

Yet there are two fundamental distinctions here that we must not gloss over:

- want (desire) versus need (viability)

- local ‘efficiency’ versus whole-of-system effectiveness

Many current business-models, and consumerist-economics in general, exhort us to prioritise want over need, because doing so ensures that the need is (‘ideally’) never satisfied. Which drives the quick-profit failure-cycle ever-faster. Which creates more and more non-resolvable waste. Which threatens whole-of-system viability. Looks great in the short-term, but in reality not such a good idea…

Simple personal example: for my own viability, I need to manage my weight, and health in general. I’m fortunate in that I don’t drink or smoke, but I do tend to fall back on comfort-food when I’m stressed (which, like most people these days, I often am). Exercise is not convenient; watching my diet is not convenient; doing meditation or suchlike to manage the stress is not convenient. I don’t want to do any of those things at all. Reality, however, is that Type-2 diabetes would definitely not be convenient… and a heart-attack or stroke even less so. Oops…

To continue the example: I want to offload my responsibility for my own health to someone else: my doctor, for example. Or, ideally, just pop the right kind of pill, and all the problems magically go away. Reality is that it just don’t work like that: in fact that way addiction lies, in all manner of seriously-nasty forms. Again, not a good idea… What I need to do instead is to find a way in which I would want to take responsibility for my own health – which is a very different concern than simplistic notions of ‘convenience’.

In fact, exactly the same applies to the over-reliance, in business and elsewhere, on IT and ‘deus-ex-machina’ in general: it’s a desire for ‘control’ over things that are inherently ‘uncontrollable’, for ‘certainty’ where, by definition, no certainty can be had. It’s a desire for things to be ‘convenient’, not real-world messy: a desire that the machine can magically take away all the effort – particularly the real-world effort of dealing with real-world people and their real-world issues. That’s all that IT-centrism is: another addiction to another kind of ‘magic pill’. And like all addiction, it doesn’t work: it can sometimes give the illusion of satisfying the short-term want, but not the real need – especially not in the longer term.

And consider, again, local versus global (‘whole-system’) – because this is where ‘convenient for whom?’ really does come into the picture. Let’s use the old inside-out versus outside-in:

And again, let’s use Chris Potts’ dictum that “Customers do not appear in our process; we appear in their experiences”.

If, as the organisation, we seek convenience from our own perspective, looking inside-out, then yes, we want all of our customers to adapt themselves to fit our processes. That’s easy for us; most-efficient, for us. But is it convenient for the customer? Often, no: too often, very far from it, in fact.

If, as the customer, we seek convenience from our own perspective, looking outside-in, then yes, we want the company to adapt itself to our desires, our needs. That’s more convenient for us; easier for us; most-efficient, for us. But is the company going to be able to do that? Given the way most systems are still built, around silos and suchlike, this can be kinda tricky…

Each of those is locally ‘efficient’, from the perspective of a single stakeholder – but not necessarily so from the global perspective of the system as a whole. There are trade-offs here, often very complex trade-offs: and if we don’t get them right, across the whole system, then the system itself is at risk of becoming non-viable.

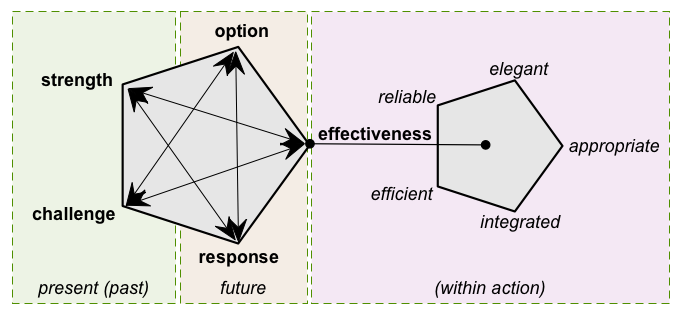

Simple illustration: if the customer’s experience is of inconvenience, then the organisation’s business-model is going to be at risk, because the customer won’t want to do business with that business. Likewise, if the organisation’s experience is that the customer is too inconvenient, then it won’t want that customer. Hence, yes, convenience is a factor here – but it’s not the only factor. Likewise, efficiency – minimum ‘waste’ from a single perspective – is a factor, but it’s not the only factor. And probably the simplest term that we have, to describe the complex melding and interaction of the relationships between all of those factors, is effectiveness. Which, in turn, I would summarise in terms of the interaction between themes such as efficient, reliable, integrated, elegant and appropriate (‘on purpose’), as illustrated in my old SCORE framework:

And the simplest way to summarise an enterprise is to describe it as an ‘ecosystem-with-purpose’ – there’s a real sense of purposiveness to an enterprise, which there usually isn’t in other types of ecosystems.

If there’s purpose, we’re going to need to be to identify when we’re ‘on-purpose’, and when we’re not. Which means that we need indicators for ‘on-purpose / not-on-purpose’. Otherwise known as success-metrics. Which, in turn, derive from the vision and values and derived-principles of the enterprise. Of which ‘convenience’, yes, may be one of those values. May. Not necessarily. Not always. Certainly not ‘the centre of everything’ – especially at the whole-of-enterprise level.

So we need to get our priorities really clear on this: convenience is, yes, often a desirable attribute of success – but it is not success itself. If we ever get this one the wrong way round, we’re in deep trouble…

Never underestimate the power of the path of least resistance. People prefer it to the most efficient path and the most effective path. The path of least resistance is actually quite a profound concept, underlying not only human behavior, but also evolution and physics. See also, principle of least effort and principle of least action. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Path_of_least_resistance

I don’t underestimate it, at all.

It’s probable that I most often see it as a problem – especially in business-models – and for all of the reasons I’ve outlined above.

And the reason I most often see it as a problem is that most people seem to underestimate the damage it can do, at a whole-of-context level, when they try to apply it both to and at too narrow a scope.

When ‘path of least resistance’ for one stakeholder-group ends up massively increasing the resistance elsewhere, we have a non-viable system. That’s exactly what causes ‘silo-wars’ and suchlike within organisations. And it also causes failure of business-models, when organisation-centricity, or even customer-centricity, demands that ‘least-resistance’ should apply only to itself, to the possible or even probable detriment of all other players.

Perhaps one of the nicest illustrations of this is the huge ‘special-case’ required to make a Penrose Triangle ‘impossible-object’ seem to make sense in the physical world. It ‘makes sense’ – provides least-resistance to ‘making-sense’ – from one viewpoint only (the right-hand photo in the images below), whereas from all other other viewpoints there may well be too much resistance against ever ‘making-sense’ at all:

In short, for an enterprise-architecture, the only way that works is that everywhere and nowhere is ‘the centre’, all at the same time. Which means that the ‘path of least resistance’ for the enterprise as a whole must be calculated from every ‘the centre’ in the enterprise – sometimes all at the same time.

Which, in most cases, will give very different results from a simplistic single-point calculation. Which, if we’re going to apply concepts such as ‘path of least resistance’ to any whole-of-enterprise architectures, is likely to be a rather important distinction…

BTW, It’s tempting use “expediency” instead of “convenience”. Then we could talk about the 3 E’s: efficiency, effectiveness, and expediency. Unfortunately, the latter has negative connotations.

Yep, ‘expediency’ does indeed have ‘negative connotations’. And, in this context, for very good reasons too – as I hope I’ve shown above.

Convenience and expediency may be useful attributes to the so-called ‘value-proposition’ for a business-model, which itself is a sub-component of one view within a business-architecture, which is arguably a component of a view of an enterprise-architecture from one player’s perspective. Don’t confuse a business-model with an enterprise-architecture: they’re not the same things at all…

To add one more point: expediency, or convenience, is actually from the perspective a single stakeholder. In that sense, it’s a sub-component – and an optional sub-component at that – of the broader theme that I’ve described in SCORE and elsewhere as ‘elegance’: the human-factors in a context. As in the SCORE diagram above, ‘elegance’ sits at the same level as ‘efficiency’ – yet both of those, in turn, are merely sub-components of overall effectiveness.

In other words, there’s a real hierarchy here that – if we want to protect viability of the system as a whole – should not be messed with or misunderstood:

- convenience is an optional sub-component of ‘elegance’

- ‘elegance’ is a (usually) non-optional component of effectiveness

- overall-effectiveness is always the core success-concern for any ecosystem and/or enterprise

In short, whilst convenience or expediency may well be relevant factors in an enterprise, do not attempt to place them at the same level as either efficiency or effectiveness. Doing so is really, really, really not a good idea… not wise at all.

Hence, also in short, don’t do it! 😐

‘Nuff said on this for now, anyway: over to you, perhaps?

The first thought I had when reading Nick’s comment is that he had a point, but missed the critical issue of context. Different people (and for that matter, the same people at different times) will have different needs.

Most of the time, I’d never consider buying groceries from a convenience store – compared to a supermarket the selection is inadequate and the prices higher. However, under the right context (after normal hours for the supermarket, don’t have time to roam through the larger store, etc.), the convenience store is what I want.

Where this becomes relevant to the enterprise is that these different contexts may be mutually exclusive. For example, brick and mortar stores have their advantages as do online retailers. You can get hybrids, but you can’t get the best of both. It’s more effective to play to your strength rather than chase something unattainable.

Yep, fully agreed.

I don’t disagree with Nick (or you, or anyone) about convenience being _a_ potential factor in the business-model / ‘value-proposition’ mix, subject to context, exactly as you say.

I _do_ disagree, and strongly, with the notion that ‘convenience’ must inherently and always have a higher priority than either efficiency or overall effectiveness for the shared-enterprise as a whole.

There’s a very big difference between the two, which to me Nick had glossed-over way too much for my comfort (or whatever).

I know I tend to be over-pernickety and over-pedantic about some of these things, but they really do matter when we start trying to bring them down into real-world practice…

Thanks Tom for your detailed response and the high level of thought you put into it. Rather than address it point by point, I’m going to try to cut to what I feel is the essential difference in our perspectives.

(By the way, I thought of a great E-word for convenience: easy! Duh, I don’t know why I didn’t of it right away.)

I get the feeling that you view the enterprise and the actors in it as classical economists view actors in the market, ie homo economicus–actors who always make rational decisions to maximize utility. When one models systems from this perspective, whether they be markets or enterprises, then efficiency and effectiveness are indeed the highest priority.

I view enterprises more like evolving ecosystems and the actors in them as having only bounded rationality, a la Herbert Simon. From this perspective, people will satisfice, not optimize; they will usually take the path of least resistance; they will make irrational decisions based on cognitive biases and emotion; etc.

When one models enterprises in this way, then easy becomes a higher priority than efficiency and effectiveness. This was the point I was trying to make (somewhat cryptically given my brevity) with my references to the principles of least effort and least action. Which, begging your pardon, I DO think you’ve underestimated. Because these are the principles manifested by the most powerful architectural process in the universe: evolution. In the closing chapter of Origin of Species, Darwin observed, “Nature is prodigal in variety, though niggard in innovation.” I would change niggard to lazy. Evolution only works because small changes are easy enough to make them possible.

Here’s another way to think about the profound importance of easy: catalysts. A catalyst in its most general sense is something that makes a change EASIER without itself being changed. Catalysts lower the “activation energy” required for a chemical reaction to take place, i.e. it makes it easier by requiring less energy/effort. Enzyme, biological catalysts, make life itself possible by making metabolic reactions “easy” at room tempurature.

Just think of how the concept of catalyst could be fruitfully applied to enterprise architecture. Instead of producing standards that maximize efficiency and effectiveness, but which people find incredibly hard to adhere to, architects could work on creating catalysts for action: constructs, tools, etc. that make it easier to do things a slightly better (more efficient/effective) way. Over time, the architect can slowly but surely keep improving the enterprise one easy baby step at a time.

If you are designing a machine, then effectiveness and efficiency may be the highest priority. If you are designing a social construct for people, like an enterprise, then easiness has to be a higher priority.

BTW, My only response to your comments on ecosystems and waste and poisoning the ecosystem is to point out a fascinating proposal called the Medea Hypothesis (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medea_hypothesis), which contends that life is never in balance, that it is always building up waste to a point that most life on earth is destroyed in a series of catastrophes. I think it is spot on. It fits very well with the Panarchy model.

Hi Nick – thanks for the thoughtful / respectful reply.

Unfortunately (as you can probably guess), I’m going to have to disagree with you on almost all of it…

@Nick: “I get the feeling that you view the enterprise and the actors in it as classical economists view actors in the market, ie homo economicus–actors who always make rational decisions to maximize utility.”

Nope. That’s a strawman. Period.

I can only guess that, to even make that suggestion at all, you either view ‘efficient’ and ‘effective’ as near-synonyms, or assume that I do. If you’d read the darn descriptions, and look at the darn diagram, you’d realise that I’m very clear that they’re not.

I repeat again: in the (yes, somewhat-simplified) model I’m using, ‘effectiveness’ is the outcome of a trade-off between five distinction components or dimensions, sometimes indicated by the acronym LEARN: ‘eLegant’, ‘Efficient’, ‘Appropriate’ (i.e. ‘on-purpose’), ‘Reliable’ and ‘iNtegrated’. Hence efficiency is merely one of the elements in that trade-off. As I said in the article, ‘easy’ is a sub-component of the ‘elegance’ component, which you have arbitrarily raised to higher priority than overall effectiveness. Which, bluntly, is dumb… a single moment’s thought should illustrate that for you. So why oh why the heck do you do it? It makes no sense at all…

To be blunt, this smacks strongly of the bizarre argument we had some while back about entropy, in which – I would still strongly assert – you insisted on placing the whole frame entirely back-to-front. Given your views on entropy, it’s ‘logical’ – a corollary of the same set of premises – that you would end up with much the same back-to-front thinking about this as well. And as with the entropy argument, I’m well aware that you could quote reams of academic authorities to back up your argument – but, to again be blunt, it still doesn’t make it any better an argument. To even further be blunt, it’s not only garbage, but damn dangerous garbage: popular with a certain subset of marketers and politicians, no doubt, to support their own short-term greed and stupidity, but in the long-run it would kill us all. As you yourself almost gleefully admit in your final comment about panarchy. Sigh…

@Nick: “Just think of how the concept of catalyst could be fruitfully applied to enterprise architecture.”

This is one of the few parts of your comments that I can actually agree with. What you’re missing is the ‘Why? – the purpose that indicates the options and choices for catalysts. Simply saying ‘a catalyst makes it easier’ misses the point – focussing solely on process rather than guiding-intent for process, which in turn indicate / support the metrics for success.

@Nick: “If you are designing a machine, then effectiveness and efficiency may be the highest priority. If you are designing a social construct for people, like an enterprise, then easiness has to be a higher priority.”

That’s another strawman – a really inadequate ‘either/or’, and one that only makes sense if you in essence treat efficiency and effectiveness as near-synonyms. If you had read the darn description above, it is very clear that ‘effectiveness’ is the trade-off of the whole – not a crass ‘either/or’, but a full ‘both/and’ (encompassing considerably more dimensions than the simplistic ‘either/or’ you’ve given above).

It’s a strawman, and an entirely spurious one at that: so drop it, please?

@Nick: “ecosystems and waste… the Medea hypothesis…”

As above, all I can say to this is that seem almost gleeful about that possibility? If so, it might be worthwhile for you to explore why?

As I understand the ‘ecosystem issues’ – and which I use as a base for my own work on whole-of-context enterprise-architectures – there is a crucial distinction between ‘natural’-ecosystems and enterprises: an enterprise is an ecosystem with purpose. To some extent, an enterprise is also a ecosystem with self-awareness, including awareness of its own feedback-loops.

What you’ve described, in the ‘Medea hypothesis’, is the ‘logical’ endpoint of an ecosystem that has no intentionality and no self-awareness: in effect, the logical endpoint of POSIWID applied on a whole-of-system scale, as also implied by the logic of your preferred concept of entropy. Yeah, that’s entirely logical – for a non-purposive, non-aware ecosystem, driven solely by the logic of (your) entropic ‘easiness’.

It doesn’t apply to enterprises – or, more accurately, it doesn’t apply to enterprise to the extent that they _are_ purposive and _are_ self-aware. Which is the whole point of enterprise-architecture, surely? – to support organisations and suchlike becoming purposive and self-aware?

As you put it, “Over time, the architect can slowly but surely keep improving the enterprise one easy baby step at a time.” Yes, agreed – but first we need to have a clear sense of what ‘improvement’ actually looks like (for whom? in what way?). Which means we need to have some concept of purpose – to compare against – and some capability for self-awareness – to be able to note how the enterprise is changing relative to that purpose.

And once we have those, we’re no longer in the same ball-game as the kind of entropic-decay ‘natural-ecosystem’ to which the Medea-hypothesis might apply: instead, we’re in a living-system ecosystem-context, which plays reverse-entropy games to keep itself going.

In which case, your position above about the elevation of ‘easiness’ to ‘the core purpose for everything’ is not so much null and void, as – by your own terms – a recipe for enterprise-suicide. Oops…

Not exactly a helpful position for enterprise-architecture, I might suggest? Hmm…

I know I’m being somewhat blunt and arrogant and the rest in saying this, but I really do think you need to go back to the drawing-board and start again from scratch. What you’ve said above might well be popular with certain of the more insane end of our so-called ‘global economics’ and suchlike, but in the larger scheme of things – the enterprise of humanity as a whole – it is so wrong, and so dangerous, that you you really need to stop right there, right now, and think – and think properly, as an architect should – about the real-world implications of what you’ve promoted above, and what you need to do to help us all to get out of that mess.

End-of-rant… 🙁 😐

But seriously, Nick, seriously: what you’ve been promoting above is not okay – not okay at all.

So don’t. Just don’t, okay?

Gene, You sound a bit like an attorney (which I used to be): every answer is “it depends…” 🙂 Which of course is true. But it is also true that even though a certain context can always change the answer, one answer dominates in most contexts. I claim that is the case with convenient/easy.

Your c-store vs g-store may not be the best example of context (ie “it depends”). Why? Take a look at this article: “Convenience ranks No. 1 in both [c-store and g-store] formats…” 🙂 Different contexts but same priority: convenience!

http://www.retailleader.com/top-story-consumer_insights-convenience_trumps_price_for_supermarket__c_store_shoppers-2396.html

Again, Nick, you appear to be confusing a minor sub-theme of business-models with enterprise-architecture as a whole.

Don’t.

Just don’t. 🙁

Never a lawyer, but my first career was in the ballpark (dealt with both civil and criminal law).

I disagree regarding one answer dominating most contexts. Case in point, let’s throw the bulk grocers (Costco, Sam’s Club, etc.) into the mix. By virtue of their relative scarcity, they violate the convenient location rule noted in the link (which is a different sort of convenience than what I was talking about), but yet they prosper.

My take on the subject is that if we use Tom’s SCORE diagram above (http://weblog.tetradian.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/SCORE-time_full.png) and think of the right hand pentagon as a radar diagram, we will see a range of different side dimensions based on the range of contexts (regardless of type of enterprise).

@Gene: “…and think of the right hand pentagon as a radar diagram…”

Yep, that’s exactly the point – thanks, Gene!

(I’ve just had a great conversation offline with Nick about this, so I think it’s all nicely disentangling itself anyway now. Kind of recursive, as in “the process of making sense of ‘

whatever‘ is itself part of ‘whatever‘”, I’d guess? 🙂 )I don’t want to dredge up things unnecessarily, but the radar diagram idea gave me the idea of “convenient” as a an effectiveness shape, an archetype.

Eg. McDonalds (extremes used for illustration, hopefully scores don’t need an explanation)

Reliable = 5

Efficient = 5

Appropriate = 1

Elegant = 1

Integrated = 5

This shape when mapped on the pentagon as a radar would give you what a “convenient” effectiveness would look like.

Another eg. Heston’s Fat Duck

Reliable = 5

Efficient = 1

Appropriate = 1

Elegant = 5

Intergrated = 1

This might be the “indulgent” effectiveness shape.

I’m sure there are a number shapes and adjectives that we could come up with.

Thanks, Chris – the radar-diagram mapping as an “effectiveness shape” is a nice concept that I hadn’t thought about before, and yes, it works really well! I need to play with that one a bit more… 🙂

I want to echo what Gene said. It is presumptive of stakeholder prerogative for architects to decide a priori what is “most important” or “fundamental” in an architecture. This should always be determined by how the stakeholders define “fitness for purpose”. Architects can certainly advise stakeholders as to things they ought to consider, and about the interactions and consequent tradeoffs between these things.

Now, I’ll agree that “effectiveness” is somewhat akin to fitness for purpose, but I can easily imagine situations efficiency and convenience are things that stakeholders would not value as things everything else must be traded off for.

len.

@Len: “I’ll agree that “effectiveness” is somewhat akin to fitness for purpose”

Wow… my bad, I’d completely missed that connection… 🙁 – it’s ‘obvious’ as soon as you say it, but I really hadn’t linked those two points before. Duh…

Hence, obviously, many thanks for that, Len! 🙂

Taking it one step further:

— purpose describes the overall intent

— fitness-for-purpose indicates whether we expect the purported ‘solution’ to deliver to the need indicated by the purpose

— effectiveness indicates how much it is fit-for-purpose, whether it has delivered to the intent of the purpose

In that sense, fitness-for-purpose is a future-view, whilst effectiveness is a past-view.

Hence, recursively, is this notion of effectiveness fit-for-purpose, for the purpose of understanding effectiveness? 🙂

Interesting topic, Tom and Nick.

Ever since enterprises have sought to be more customer oriented, the outcome of convenience has been added to the traditional outcomes of efficiency and effectiveness.

The old chestnuts come from a product view of the world. Convenience entered and has become increasingly important in a service view of the world. The increasing proportion of our economies that are encompassed within the service economy is testament to the change that has been occurring over the last five decades.

This has taken a while to emerge in the ICT enabled world because systems started off supporting internal processes, and supporting functions, some of which still do not identify themselves in service terms (read HR and finance – but that is a separate story!!).

So, I was quite interested to see convenience alongside efficient and effective. No surprise at all. When was the first time this word came into my architecture world? When I worked on red tape reduction initiatives, seeking to improve the interface between government and its customers – businesses and citizens. When was it most dominant – last year, when working on the architecture to enhance the digital experience of students at a University. I don’t think it will disappear from the list of top considerations.

Is there a king of the castle? Is there a dominant outcome or decision factor? Of course not! Must organisations deliver value to customers and value to their owners? Yes, so all three outcomes remain on the table.