Why the ‘why’ matters

In any real-world practice, why do we need to explain the ‘why’ as much as the ‘how’ and ‘with-what’?

Here’s a first-hand answer to that question…

Way back when (almost half a century ago: yikes…), I took a school-vacation job as a farm-labourer. Okay, I was a gawky, bookish kid, but we lived in a country district, and it was about the only short-term paid-work available there for a 16year-old. Fun, too, after a fashion: and hey, I got to drive a tractor! For real! Wow!

Came the day, though, when the farmer told me to clean up the newly-mown hay in the hay-field, which looked like this:

He told me the what: rake all of the hay into wider-spaced rows, ready for the baler.

He told me the how: go up and down the field with the tractor, towing a big self-powered hay-rake like this one:

Overall, we’d say that he gave me a full set of work-instructions – but not the principles, the deeper ‘why‘ behind those work-instructions. Oops…

Anyway, off he went, back whatever one of the thousand-and-one other things that need doing on a farm at harvest-time he needed to do next, and left me to it. So there I was, sitting on my tractor, going up and down the field, doing what I’d been told, making nice neat rows of hay, much like this guy:

I felt pretty smug and pretty proud of myself: hey, not bad for a gawky, bookish 16year-old, right?

Not long after I’d started, though, it came on to rain. Not much, at first, but I didn’t have my jacket, so I was going to get a bit wet. Oh well. But I had a job to do, didn’t I? – so getting wet was just part of that job, wasn’t it? Dedicated, committed, a Good Worker – I was going to prove all of that to the farmer, I was sure of it.

Then it came on to really rain. Heavy. Not just wet, really wet. Yuk. But I kept on going: I’d been told to do this job, and I was going to see it through right to the end.

An hour later, I’d finally finished the whole field, and I drove the tractor back to the farm, a mile or so away. I was soaked right through, sodden, dripping, but I was pretty pleased with myself, to be honest.

The farmer was furious.

And with good reason, too – because without quite a bit of extra work, and at least a couple of very sunny, very dry days, my misguided dedication to doing the job to the end could well have ruined the whole crop.

Idiot…

But actually, not all that surprising, under the circumstances – and not just because I was a gawky, bookish 16year-old. He’d told me the what, and the how, and the with-what. But he hadn’t told me me the why for that task – the reasons behind it. Without those reasons, I could keep going all right, but I couldn’t know when and why to stop – and, especially, not when and why to stop early, with the job seemingly incomplete.

One of those reasons was, yes, to rake the hay up into rows that would be easier for the baler: that part I’d understood on my own, not least because I’d often seen a baler in action before, in the fields next to our home. But what I hadn’t known – and the ‘why’ that he hadn’t bothered to tell me – was that the hay needed to be dry before being raked into baler-ready rows. If it wasn’t dry, it would likely rot in the bales – not only rendering the hay unusable as stock-feed, but getting so hot in the process that it could well catch fire. Haystack-fires are one of the more devastating disasters that can befall a farm – and they can be triggered off by just one bad bale. Hence why raking soaking-wet hay into dense rows that couldn’t dry out on their own was not a good idea…

Okay, he could have sort-of helped me do it better, by applying another business-rule: “don’t rake in the rain”. That’s the way we’d do it with most automation, after all. But business-rules alone don’t help with unknown uncertainties, the ‘It depends’ and ‘Just enough’ that pervade right through every real-world context. In this case, there was real pressure to get the job done; a little bit of rain wouldn’t matter much on an otherwise dry day, but heavy rain on unraked hay would matter a lot; and already-raked rows could shrug off the rain better than unraked hay. It depends… it depends… and what it depends on is often trade-offs that are too-subtle for over-simplistic sets of business-rules. Kinda tricky, all round… and without knowing the ‘why‘, there’s no way to work out those trade-offs into an appropriate answer for each specific context.

Which, overall, we could summarise as follows:

- To do the job, we need to know the what, the how, the with-what, the where, the when.

- To do the job properly, in the face of real-world uncertainties, we also need to know the why.

Straightforward enough, in principle. But not necessarily straightforward in practice. That’s the problem.

Practical implications

On the surface, this story is about one mistake made just one teenager, half a century ago, in a business-domain that’s a long way different from most of what happens now.

In reality, all of this happens a lot, for exactly the same reasons, in just about every business-domain, right here, right now. That should be clear enough for any business-analyst or enterprise-architect or whatever who knows how to jump up to generic-abstracts and bring it back down to the real-world again.

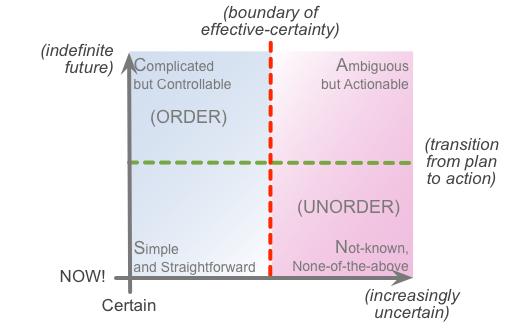

To illustrate this, let’s look at it in terms of the SCAN sensemaking/decision-making framework:

In most practical cases – and, in particular, in most automation – we start off with a Simple set of work-instructions, with any real-time decision-making handled by predefined business-rules. As per classic Taylorism and the like, all of this is typically prepared and planned out in the Complicated domain, away from distractions and confusions of real-time work.

To handle special-cases and other complications at real-time, we add more business-rules, and more business-rules, and yet more business-rules, each of which enables us to extend order and control over the context just that little bit further. Eventually, however, we hit up against a boundary of effective-certainty, beyond which either we transition over into diminishing-returns – where the effort of selecting and executing against yet another business-rule costs more than can be achieved by doing so – or else there simply isn’t time any more to execute all of those business-rules. That boundary of effective-certainty is also as far as almost any automation can currently go. Beyond that boundary, we’re into unknown-territory: either the existing business-rules won’t help us, or – as in that example above – the lack of any available form of guidance means that we’re increasingly likely to get a bad end-result. To make it work, we need something that can guide in the midst of often-unknowable uncertainty.

That’s where principles come into the picture. The crucial distinction is this:

- rules work against uncertainty

- principles work with uncertainty

Both are valid and useful, but they’re fundamentally different in nature and purpose: don’t mix them up!

As with business-rules for Simple work-instructions, principles are typically developed away from real-time – in this case in the Ambiguous domain, feeding down into the Not-known, as a kind of unorder-oriented complement to classic order-oriented Taylorism, and as a counterpoint to mitigate against the latter’s constraints.

We need those principles, in order to work with the unorder of the real-world – and we need appropriate means to execute with those principles, too. That’s part of the dangers of excessive over-emphasis on automation: a gawky 16year-old may not be much good as yet in working with those unorder-oriented principles, but most current automation has no grasp of them at all (hence the cry of yet another agonised programmer at our office, yelling his computer “don’t do what I say, do what I mean!” 🙂 ). And if the respective system can’t cope with real-world unorder, it will fail at some point, probably ‘without warning’. Not a good idea… You Have Been Warned?

The overall moral of this little tale? To do anything in the real-world, we need to know the what, the with-what, the how; but to make it work well, even in the midst of the unknown, we need to know the why.

That’s why the ‘why’ matters.

Over to you for comment, perhaps?

I’m 100% with you on the need for understanding why, but I suspect that’s because I’m a “why-person”, and that’s “rub number 1”. In my experience, an individual is likely to be a why-person, a what-person or a how-person, i.e., they have a preferred form of instruction, and if you give them a different form of instruction, “your results may differ”.

If you give a why-person detailed how-instructions with the admonition, “follow these (how-)instructions exactly”, their immediate reaction is likely to be “why?”. If they are obedient, they may follow your how-instructions to the letter, but while doing so they will likely be trying to figure out what it is you are trying to accomplish and why. If you give a how-person why-instructions, they will almost certainly ask you what you want them to do and how you want them to do it. They will then ignore the why- and what-instructions. The why-instructions are completely irrelevant, and the what-instructions become irrelevant once you have provided the how-instructions.

The point is that if you want someone to achieve for you the outcome that you desire, you have to tailor your instructions to their preferred form. More importantly, within that form, you have to provide that person with ALL the instructions necessary, FOR THAT PERSON.

Avoid the temptation to assume that why-people are in any sense better able to get the right thing done well than how-people. Because the why of a situation is often murky (for example, if the instructions were passed down from higher up the management chain), and asking “why” is often viewed as some form of insubordination (i.e., the only “why” that matters is “because I said so”), why-people, who are only seeking a more comfortable context for what they have been asked to do, almost always out of a sincere desire to “do a better job”, can often mis-infer the desired outcome (“what”)and the reason that outcome is desired (“why”) from the provided “how”.

“Rub number 2” is that I have a hard time thinking of “don’t rake the hay if it’s raining” as a “why”. It feels to me more like a “when”, i.e., a specific kind of “how”. It doesn’t describe a desired outcome, except by implication — hay that is not rotted, or worse, charred. Nor does it describe the motivation (“I need the hay in bales, to store, use in appropriately sized units, or to take to market”), for the desired outcome of “dry hay ready for baling”.

The desired outcome could have been effected had you correctly inferred it, or had the farmer provided it to you. Because he didn’t, you inferred the desired outcome was “hay ready for baling”, because, and quite reasonably so, your lack of experience with haying led you to overlook the “dry” qualifier. Probably all the hay you had ever experienced was dry, so the possibility of hay being wet, and the possible dire consequences thereof, never entered into your thinking. And the farmer probably thought it was obvious that one would never bale wet hay. It certainly was to the people he hung out with.

len.