Platform, toolset and tool

With all of this exploration on new toolsets for enterprise-architecture and the like, what exactly are we talking about here?

Is the aim to create some kind of ‘super-tool’ or toolset that will do absolutely everything, all in one go – like Chris Lockhart’s ironic ‘SUFFE™‘, a supposed Single Unified Framework For Everything?

Short answer is ‘No’. As I see it, that’s not only not feasible, it’s probably not even desirable.

The real aim is something much more modest, and, I hope, much more achievable: a platform to link tools together.

I’ve been nibbling away at this for many years now, but a quick practical overview of the reasoning behind all of this is in the blog-post just before this one, ‘Toolsets, pinball and un-dotting the joins‘. Perhaps the simplest summary is that we each have vast numbers – often hundreds – of tools and methods that we use within our work; but everyone uses a different toolset, and almost none of the tools will share information with each other anyway, so it’s real easy to lose track – especially over longer periods of time, and/or in a collaborative environment. In short, our toolsets are a mess, and we really need to do better – if only to set an example to others, as their enterprise-architects!

So how do we cope with those two concerns? – that:

- everyone uses a different toolset – some of them electronic, many of them not – and often a different set of methods, too

- almost none of the tools – even the electronic ones – will link together, or share data with each other

To me the answer is a platform that consists of just two core elements:

- a standard data-structure that provides a consistent way to describe ‘things’, and relationships between those ‘things’

- a standard way to define tools (‘editors’) that can act on that standard data-structure

At first glance, that probably doesn’t look much different from what we see with just about every other software-based toolset. Yet there’s a fundamental shift in perspective here that underpins all of this, that changes the entire way in which we use a toolset.

The usual approach is ‘model-first‘: define a model-type – Archimate, for example, or UML – with a metamodel that defines all of the types of permitted objects and relationships that can be created, modelled, edited and stored in some model-specific repository. Everything centres around the model-type, with all ‘things’ subordinate to and ‘owned by’ that model-type. That’s one of the main reasons why we have so much difficulty linking across a whole architecture: each of the model-types is different, and has rigid rules about what it will and won’t allow.

In this approach, though, we switch it the other way round: ‘thing-first‘, not ‘model-first’. Everything centres around the ‘things’ – not the model-types. Each model-type can add its own identifiers and parameters to things, and within its own context can apply its own formal-rigour to relationships and the like: but ultimately each thing is ‘owned’ solely by itself. A ‘thing’ accretes parameters and relationships, but is not defined by them, by the model-types that apply and edit those parameters. Ultimately, at the detail-level, each ‘thing’ may have its own unique data-structure, distinct from every other type and instance of ‘thing’: and yet because there is an overall consistency of structure – a meta-structure – that is still shared by every one of those ‘things’, it is still possible to link any ‘thing’ to any other ‘thing’ in any way that we need. The result is a data-platform that is capable of linking anything to anything else across the whole of an architecture – whatever tools we wish to use.

The other side of the platform is about tools – the ‘editors‘ that act on that data-structure. This is where we come back to those crucial points that “we each have a vast array of tools that we use”, and that “everyone uses a different toolset” – a different mix of tools. What that tells us straight away is that there’s no point in trying to build ‘The Single Tool That Will Do Everything’ – because in practice someone will always want to add ‘just another feature’, and it’ll never be done. Instead, again, we turn it round: we build a framework that can accept just about any tool or way-of-working, and within which people can define their own tools in whatever way they want.

(In principle, at least, if perhaps never quite fully so in practice – and even then, to be honest, it’ll take us some while even to implement enough to cover most of the more-common needs. But “define and use whatever tool you need” is the idea and ideal, anyway.)

So to answer a query from Peter Bakker:

I’m still not sure … if/how you are going to support my assumption/problem-solving map.

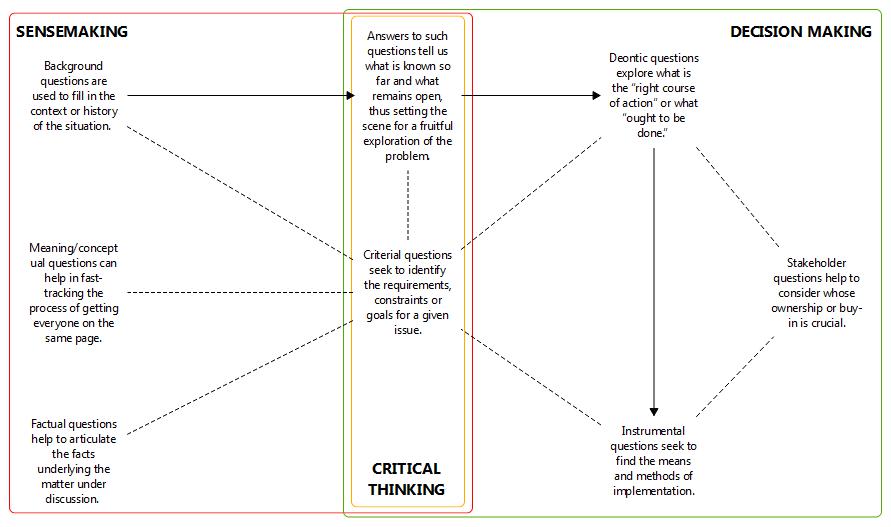

Which map looks like this:

The short-answer to “if” is “Yes, but you’ll probably need (or prefer) to define it yourself”. In fact that’s not just the short-answer, it’s the complete-answer to that “if”: what we’re working on will be able to support a user-defined ‘editor’ for assessments based on that kind of context-map.

And the short-answer to ‘how” is “Via an editor-definition language, which Peter can use himself to create an editor for his own tool”. For that, though, the complete-answer would be a lot longer: several blog-posts worth, in fact, just to give a detailed overview, let alone anything else. Yeah, unfortunately this part is going to take a while, whether we like it or not… – and we do need to be realistic about that. Even so, as per the previous posts in this series, we probably do have enough understanding of what’s needed, from an architectural perspective, to begin making a real start on implementing it right now.

In the later part of the post ‘And more on toolsets for EA‘, there’s a brief summary of what would be in an ‘editor-definition’. (I also have perhaps a hundred pages of detail-notes on this, scattered around in various notebooks here, so it’s quite a bit further on in terms of design and development than implied in just that one summary.) In essence, an editor is actually just another type of ‘thing’, but with a specific data-structure that defines the structure and default-content of the objects that it would create or edit; any other data that it might need, for pulldown-lists and settings-parameters and suchlike; and the functionality of the ‘views’ through which it would act as an editor.

None of this will work, of course, without a software-platform through which it could act. Again, there’s an overview on a suggested ‘plug-in’-based architecture for this, in the later part of that post ‘And more on toolsets for EA’. I’ll admit that that architecture still needs quite a bit more detail to be fleshed-out before we can get properly started, but the core ideas do seem ‘doable’, at any rate – for a web-app , at least, with other options and hardware-platforms later. Ultimately we would want software-apps that could support this concept across every aspect of the toolset-ecosystem, from multi-screen ‘war-room’ setups right down to feature-phones and even, via SMS/MMS, to dumb-phones. And although the standard data-structure and standard for editor-definition do need to be non-proprietary, there’s no reason at all why some of those software-apps should not be commercial-offerings, with all the extra polish and presence that that implies. As long as they do support that standard data-structure and editor-definition model, the details of the implementations themselves really don’t matter all that much at all.

The real trick that will make this work is to develop it step-by-step, with work on data-structure, data-repository, editor-definition and actual app all moving onward in parallel: or, as Phil Beauvoir put it, “We move from one MVP to the next MVP.” (Another concept that I really like for this is Jack Martin Leith‘s ‘From Now to New’ – see Stuart Boardman’s Open Group blogs ‘The death of planning‘ and ‘“New Now” planning‘.) In the ‘Editors’ section of the post ‘New toolsets for enterprise-architecture‘, I suggested that the build-order for editor-support – in other words, ‘from MVP to MVP’ – would be something like the following:

- basic form-based create, view and edit (provides base-functionality for all data-object creation and edit)

- basic linker (provides base-functionality for all linking)

- basic grouper (provides base-functionality for all ‘group’-types – sessions, themes, topics, project etc)

- tabular-type edit (provides support for table-based interfaces and data)

- basic graphic-base (provides base-functionality for scalable background-graphics and image-maps)

- free-form sketcher (provides drawing capability, including user-selected image-maps)

- builder/linker (provides functionality to support object-plus-link models such as Archimate)

- media-capture and embed (uses links to device-hardware for audio, photo, video – embed by value [data] or by reference [URL etc])

(In the longer-term we’d aim to go even further than that, but realistically just to get that far is likely to take us at least a year, even with experienced app-development help behind us. Step-by-step, remember? 🙂 )

If that is the sequence in which we develop editor-support within the demonstrator-app and its user-interface, then we should be able to support increasing support for Peter’s tool above as follows:

- in Step 1: a set of form-fields representing the content for each ‘domain’ of the tool, either on ‘things’ created by this tool, or appended to existing ‘things’

- in Step 2: customised links between ‘things’ developed with the tool, and also links to ‘things’ developed in other tools

- in Step 3: customised groups of ‘things’ developed with this tool, or optionally in heterogeneous clusters of ‘things’ from different tools

- in Step 5: a tool looking much closer to the diagram above, probably with content-blocks dropped onto the base-diagram as graphic ‘tabs’ or ‘sticky-notes’

- in Step 6: include the ability to do free-form sketching on the base-diagram, marking out regions as ‘things’ in their own right

- in Step 8: capture a photograph of a sketch-model drawn on a whiteboard or paper pad, and tag it as associated with this tool, including marking out regions or adding graphic ‘sticky-notes etc as appropriate

We’d perhaps need to rewrite the editor-definition for the tool with each increase of functionality – but the basic principle of how to do that, all the way up to quite a bit more than Peter suggested in his diagram above, is already in the roadmap, MVP by MVP.

So again, it’s not a single tool that we’re talking about here, but a platform that can support just about any tool that anyone wants to use, and wants to link up with other content across the whole of the enterprise-space.

As I say, there’ll be a lot more about this over the coming weeks and months, but I hope that that gives enough for a start?

(And yes, anyone who’d like to be involved in this, please get in touch? – many thanks!)

Tom, your goal here addresses a problem Ed Harrington and I were discussing yesterday – how to find a more formal, semantically rich way of representing ideas we’ve been working on (and publishing – the “Onion” stuff) recently without being restricted by the inadequate vision/scope/assumptions of current modeling languages. It will also be important to be able to use varying types of visualization that are appropriate for the intended audience(s).

Thinking about the “thing first” meta-structure, it occurred to me that the UDEF (an Open Group standard currently being re-worked) might play a useful part in that. Ron Schuldt is really the man to talk to but, if you don’t know it, I can give you a brief introduction.

I agree that development of tooling (platform) needs to proceed more or less in parallel. It’s certainly not going to be easy but done in the agile manner you suggest it should be possible. The trick will be to find some hackers, who can throw a prototype together without too much fuss. That’s not me but I’ll look around.

Thanks for the reminder on UDEF, Stuart – good point.

On implementation, I’m not the right person either – very much not – but right now I seem to be the only one who’s up there to do it, so I’m getting on with it as best I can (i.e. not very fast, and not done well, but at least it’s something). If I can get it at least to a wobbly proof-of-concept, then with luck someone more competent might become interested enough to take over. But we have to get it to that first stage ourselves, I suspect. (Back to the grindstone… 🙂 )

Hi Tom,

“Via an editor-definition language, which Peter can use himself to create an editor for his own tool”

I’m still a bit confused, do I need to create my own tool and incorporate the definition language (library)? Or is the idea that you/somebody will create a basic editor which I can adapt to my own needs by playing with the editor-definition language?

Mostly the latter (“create a basic editor which I can adapt to my own needs by playing with the editor-definition language”), though if we can make the whole thing fully open-source, quite possibly the former as well. 🙂

The idea is that every editor is a plug-in, that uses built-in functionality so you don’t have to write it. Any graphics that you need could be bundled in with the editor definition, or side-loaded from another URL, or maybe even drawn inside the tool, or whatever.

In the longer-term I would hope that we would have an editor-builder module that allows people to build their own tools inside the toolset. But in the earlier stages, we’ll probably have to make do with a text-based definition.

Remember that a lot of this is still only ideas and thought-experiments: we’ve probably now reached a point in the software-architecture where we can make a real start on implementation, but there’ll still be a lot of practical details and hard-work on coding to go through before this becomes a usable reality.