Effectiveness for enterprise-effectiveness

Keep it simple.

Simple, yet not simplistic.

Acknowledge the complexity, yet don’t ever push that complexity in people’s faces. (Not until they’re ready for it and choose to face it, anyway.)

Help people find their own effectiveness about creating effectiveness.

That’s the real core to enterprise-effectiveness.

So let’s apply some of those principles of effectiveness to enterprise-effectiveness itself.

Keep it simple, without being simplistic.

Let’s start with one obvious point that’s been the focus of too many arguments: what is ‘the enterprise’?

If we strip that right down to its basics, what we get to is its literal meaning, of ‘enterprise’ as ‘a bold endeavour’. There’s nothing there that requires an enterprise to be a commercial venture, or a business, or particularly risky: it’s just some kind of endeavour that’s sort of bold in the sense that it has some kind of challenge in it. That’s about it, really.

Or, in short, ‘the enterprise’ is whatever we choose to say that it is.

Simple.

Yet which also means that we need to say what bounds we’ve chosen – because otherwise no-one else will know.

Kinda obvious when we put it like that. But far too often forgotten…

Let’s link that to another theme, that in working on ‘an enterprise as system’, everywhere and nowhere is ‘the centre’ of that system, all at the same time. In effect, ‘the centre of attention’ is wherever we say that it is – as long as we remember that everywhere else in the enterprise will also be ‘the centre’ at some point too.

Which means that perspective kinda matters here. And for, I use a simple structure of ‘inside-in, inside-out, outside-in, outside-out‘:

Inside-in is whatever we’re working on at the moment, our current ‘the centre’. We’re looking at it in terms of itself. We’ll probably focus most on efficiency and reliability – doing its job with the minimum of waste and fuss.

Inside-out is about making use of what it is that this does. Again, we’re likely to focus on efficiency and reliability, but often only from our own view of the world, the enterprise, the story.

To make it work – make it useful, make it part of a broader enterprise – we need to connect across to and with the ‘outside-world’, itself kinda looking ‘inward’ at our part of the enterprise-story. Here, we’re likely to focus more on appropriateness and what we might call elegance – connecting with people, in ways that do with the shared-story.

And then there’s the shared-story itself, in its own terms, that in effect defines what the enterprise is – what we might describe as ‘outside-out’. To connect with that, we’d focus again on appropriateness, but also even more on integration, how everything links together to support that overall ‘bold endeavour’ of the shared-enterprise.

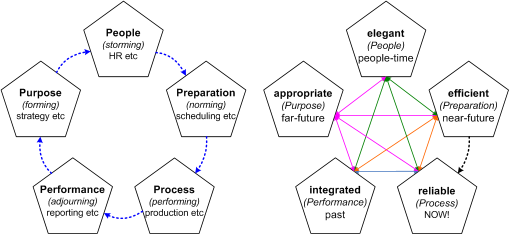

And we can link all of this together through simple frames – simple visual-checklists – that help us to keep our attention moving around throughout each of those contexts. These can remind us, for example, to focus alternately on themes such as leadership, phases of activity, the tasks to be done in those phases, different time-perspectives, and, yes, those themes of effectiveness, all interweaving with and interdependent on each other:

Yet enterprise – being enterprising – is also first and foremost about people, working together within and towards a shared-story.

Which means that we need to explore and engage with the stakeholders in that story.

Of whom there can be a lot more than we might expect…

To build effectiveness about this aspect of enterprise, let’s go back to that set of perspectives again, and look at them in another way.

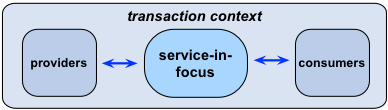

In general, I prefer to use a service-oriented approach to most architecture-type work, so I’d suggest reframing our ‘Inside-In’ – our current area of attention within the overall enterprise – as ‘the service-in-focus‘:

Some might describe this as a ‘White-Box’ view – we want to know the practical, internal details of how the service works. The stakeholders here are all the ‘usual suspects’ that we’d pick up from the org-chart, work-rosters and so on. Again, we’d probably focus most on efficiency and reliability, but also with an explicit awareness of the people-aspects – which means that we’d need to include some emphasis on elegance and appropriateness, the whole story that engages people in getting this service to work in the most effective way that we can.

We then move to the ‘Inside-Out’ perspective, the various points of contact with others from outside the service – the parts of the context for our service within which transactions take place:

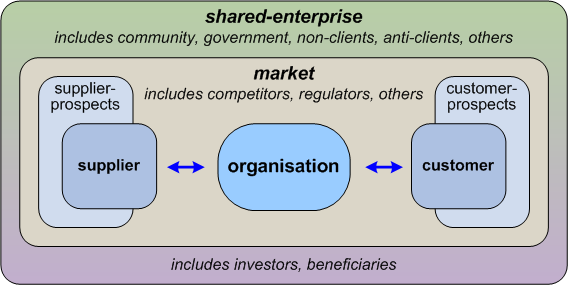

We might describe this as a ‘Black-Box’ view of the service, its APIs, its contracts, its touchpoints and the like – but ideally without needing any detail about the internal workings of the service itself. The stakeholders here are those of the service itself, together with all of the people who do or guide transactions: customers, suppliers, prospective customers and suppliers, and anyone else with whom the service would share a ‘customer-journey’.

We need to remember too that all of those ‘external’ stakeholders will be looking ‘Outside-In’, from their perspectives, in context of their needs, rather than solely for the service’s own ease and benefit. It’s at this point that we need to recognise that ‘efficient’ and ‘reliable’ and the like will start to have multiple meanings, often in conflict with each other… – hence why checklist-frameworks such as Nigel Green and Carl Bate’s VPEC-T (Values, Policies, Events, Content, Trust) have very real value here:

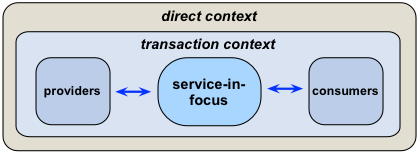

Yet there’s another aspect to ‘Outside-In’, with stakeholders who may not have transactions as such with the service, but do still have direct interactions with it. We might summarise this as the direct context for the service:

The stakeholders here are also looking at the service ‘Outside-In’, each in their own ways, but with direct impacts on the service and its relations with the ‘outside-world’. These stakeholders include regulators, for example, or complaints-arbitration bodies, who define the context for ‘fair pricing’ and ‘fair relationships’ with the transaction-stakeholders. They include recruiters, trainers, analysts, journalists and many others who interact rather than transact with the service. They include employees as employees – particularly those elsewhere in the organisation that operates the service. And, of course, there are ‘the competition’ – where such competition is relevant, which it isn’t in some types of context.

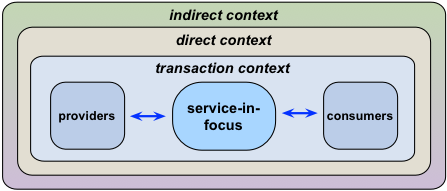

Further out again, there’s the set of perspectives that form the ‘Outside-Out’ view of the enterprise – in essence, the shared-story that would continue onward even if the service-in-focus did not exist. Stakeholders here would not have any direct transactions with the service as such, and what interactions they might have with it, or to it, or around it, or whatever, are kinda sideways-on, or more indirect – hence probably simplest to describe this as the indirect-context for the service:

Out here there can be a very wide range of stakeholders: government in general, for example; communities within which the service operates; the families of employees and others; non-clients, who are in the same shared-enterprise but don’t or can’t transact – because they’re in a different country, for example – and anti-clients, who are in the same shared-story but vehemently disagree with how the service operates within it. Each of those groups has their own distinct and disparate drivers, their own relationships with the service and the shared-story: the one thing they have in common is that they’re potentially affected by the service, and can potentially affect it in turn – a fact that we ignore at our peril…

The key point is that that structure – the service-in-focus, and those three layers of context – applies in every case, at every level, regardless of what we might choose as ‘the service-in-focus’. For example, if we place our focus on the organisation-as-whole – such as via its business-models, for example – we’d end up with a context-map that would look something like this:

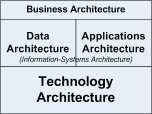

But if we were to do it just for a specific segment of the organisation, well down into the detail-layers of, say, the hardware-aspects of an IT-architecture, then the structure might look somewhat like the classic ‘BDAT-stack’:

In that type of case – typical for most classic IT-centric ‘enterprise’-architectures – the data and applications are, in essence, the transaction-context for the technology-hardware, and whilst the business-drivers provide the direct-interactions context.

(The indirect-interactions context rarely gets any mention in mainstream ‘enterprise’-architecture frameworks, which is one reason why they’re a lot less effective than most people seem to expect. Another is that the frameworks tend to hold the focus on efficiency above all else – which, however, is only one subset of overall effectiveness.)

Notice, though, that we can’t run the structure the other way round. The context is always broader than the service-in-focus – typically at least three steps broader, as in the ‘inside-in’ to ‘outside-out’ structure above. So in this case, ‘Business-Architecture’, ‘Data-Architecture’ and ‘Applications-Architecture’ form the context for the services-in-focus here, the ‘Technology-Architecture’. If we want to focus on data-architecture, applications-architecture, or business-architecture, we need to find the respective broader-context for each of those, as the respective services-in-context. What this warns us is that the ‘BDAT-stack’ should only be used for IT technology-architectures: it does not describe the context properly for anything broader than that.

Anyway, back to the practical point here:

- effectiveness comes from the intersections and interdependences of a swathe of ‘non-functional‘ factors, which we could perhaps simplify down to five key themes: efficient, reliable, elegant, integrated, appropriate

- enterprise is ‘a bold endeavour’ of some kind that, in essence, is what we choose to say that it is – there are typical sets of relationships that describe the context for an enterprise, but no fixed definitions beyond that

- enterprise effectiveness arises from paying proper attention to effectiveness in the enterprise

We might also note that simplicity is an attribute that arises perhaps most from and for elegance – the more people-oriented aspects of effectiveness. Hence why models and frameworks that are simple, yet not simplistic, can help a great deal in guiding that ‘proper attention to effectiveness in the enterprise’.

So let’s keep it simple.

Keep the models and frameworks simple.

Simple, yet not simplistic.

Everywhere in the enterprise.

Help people find their own effectiveness about creating effectiveness – effective for the needs of everyone in the enterprise.

More to follow on this, but best leave it there for now, I’d guess?

Hi Tom,

Great reading as always. May I comment that Gertrude Stein’s comment on Oakland (“There’s no there, there.”) can be improved upon in terms of a definition of the firm? You are certainly family with Ronald Coase, although having checked I don’t see you’ve written anything about EA and Coase. He is of course the economist noted for defining why firms exist as related to transaction costs. And his work has been updated by subsequent work by others, for example Williamson. Nevertheless, there is an economic reality to firms that define their size and span of functions. One could go deeper and ask why anyone would want to “enterprise” in the first place; at some point “homo faber” is as far as one can go. Nevertheless it seems to met that economics provides a nice boundary around the concept of the firm. I’m curious as to whether this fits in with your vision of EA and the firm?

Keep up the great work.

John

Thanks, John.

I’ll admit that whilst I know of Coase’s work, I wouldn’t say that I ‘know’ it in any useful sense – not much more than the usual taglines about it, really. So I wouldn’t be able to answer that part of your question without, uh, a lot of reading that I’m probably not well-equipped to do..

The real problem, perhaps, is that I’m now near-allergic to mainstream ‘economics’: I regard it as some of the most dysfunctional garbage behind the present cultural failures that we face. (Hence a fair bit of my work on RBPEA is about ways to repair the damage, as you may have seen.)

@John: “Nevertheless it seems to met that economics provides a nice boundary around the concept of the firm. I’m curious as to whether this fits in with your vision of EA and the firm?”

I don’t really have “a concept of the firm” as such, nor really “a vision of EA and the firm”. I know that other people tend to focus a lot on such themes, and I note that ‘the organisation’ or ‘the firm’ is typically bounded by legally-defined limits of responsibility (or, in too many cases, legally-condoned evasions of responsibility…), but I don’t regard any of those as fundamental to EA itself. Instead, for EA (or its equivalents), I tend to view ‘enterprise’ as a loose synonym for ‘system’, and thence look more to the ISO42010 definition of ‘system’, which is essentially fractal, taking on whatever boundaries we choose, that fit the needs for the context.

In that sense, ‘the firm’ or ‘the organisation’ is merely one possible boundary-set amongst a near-infinity that we could choose for EA (or its equivalents). That versatility becomes extremely important when we need to understand architectures across outsource-boundaries (including Cloud etc), across consortia, over multi-way business-models, across customer-journey interactions, or my own focus-area of anticlient interactions. It’s also useful for ‘inside-the-organisation’ architectures such as in classic IT-centric ‘enterprise’-architecture. In that sense, being required to be constrained to a single boundary-definition for architecture-scope can be a huge hindrance, and something I’d strongly recommend to avoid if at all possible.

Makes sense, I hope?

> Nevertheless it seems to met that economics provides a nice boundary around the concept of the firm. I’m curious as to whether this fits in with your vision of EA and the firm?

This depends on what you mean by economics and by firm.

An enterprise can be an undertaking of an individual, a team, a business unit, an organisation, a combination of multiple parts of organisations (eg. criminal justice system), an industry, a region, a nation, etc. Firm seems far too limiting to me.

Agreed, Peter – and thanks.

(And you’ve just said in one sentence – “An enterprise can be…” etc – what took me several tangled paragraphs to, uh, fail to explain. I need to do more work on my précis, I fear… 🙁 🙂 )

Tom,

Absolutely fascinating discussion, and for multiple reasons. Here are a few comments (and please forgive the temerity for offering this note!):

1) MICRO VS MACRO ECONOMICS — There’s economics and there’s economics. Microeconomics (really the purview of Coase and theory-of-the-firm types) is about the fundamental building blocks of economic behaviour – and thus possibly with some claim on having serious value. Macroeconomics, conducted at the level of government, nation or region, is usually what those who distrust economics think of first . . . and reasonably so (which is not to say that either domain are without value).

2) SCARCITY — It seems to me that economics is worthwhile, because it concerns the systematic modelling of decisions around the allocation of scarce resources. When I first heard this as a teenager, I wasn’t happy; it took a while to realize that life is substantially about choice and scarcity, even when one is privileged to grow up in Canada. Here’s a contemporary example: Lots of senior executives on either biz or tech side decide not to allocate scarce resources to EA . . .

3) VARIETY — You are correct that the “firm” is only one kind of organization, there are governments, non-profit and possibly other kinds of “enterprise” for sure.

4) IDENTITY — There’s a growing literature about “strategy” and “identity”, to wit that organizational identity is an important aspect of organizational persistence. And that good strategy likely supports enterprise identity.

Why mention identity? Because it seems that identity is also what is defined by the Coasean organization. (An enterprise identity could be thought of as a set of common interrelated actors and activities, with the purpose of executing some work according to a purpose, and around which there is a boundary or border, beyond which that set definition no longer holds.)

6) SYSTEMS THEORY — I agree with you about the idea of system as one of the best ways of looking at organized enterprise. There are of course different kinds of systems, likely overlapping. A firm is an economic actor, a fictional legal person, a cybernetic system with inputs and outputs, and even a system of discourse and a sociological community.

7) BOUNDARIES — But all of these versions of entities have boundaries. Without boundaries it seems to me to be logically impossible (inductively) to actual construct and model an enterprise, which presumably is the goal of EA.

Jorge Borges well-known 1962 “Library of Babel” short story, which features an infinite library of texts, including both meaningless texts and texts that are meaningful, is sort of a model of meaning without boundaries (it’s almost a kind of literary fractal). Certainly your work is very much about defining meaning for EA, and thus every concept has a boundary. My suggestion is that the work of Coase (or similar) can provide an external boundary against indeterminacy, the better to stop the fractal.

Let’s not get into the question of the indeterminacy of an economic system itself! : )

Sincerely,

John

Business Decision Models Inc.

@JohnHMorris (Twitter)

Many thanks, John – and please, no ‘forgiveness’ required at all! 🙂

1) It’s actually microeconomics that I question even more than macroeconomics, because I fundamentally reject its core assumptions around property’-rights’, artificial-scarcities (your #2), the money-system, monetary ‘valuation’ and its concomitant price-value mismatches, and much more.

The point I’ve made extensively elsewhere is that is no way to make a possession-based economics sustainable – and both mainstream microeconomics and mainstream macroeconomics presume a possession-based economy, which means that they are inherently dysfunctional before they even get started. (And yeah, we have to go quite a long way down the rabbit-hole before we can even begin to sort out this mess…)

2) On scarcity, we need to distinguish between genuine scarcities versus artificial-scarcities. Since much of mainstream-economics is built around the latter, we have a serious problem there before we even start…

3) On variety, yes, strongly agreed. It’s one reason why I prefer to use the more generic term ‘the organisation’ rather than ‘the firm’.

4) On identity, I’ve gone into this in some depth in various posts here, such as ‘Organisation and enterprise‘. Quick summary of the way I view the distinctions is that ‘organisation’ is the ‘how’, a legal entity bounded by rules, roles and responsibilities, whereas ‘enterprise’ is the ‘why’, an emotive or aspirational entity bounded by vision, values and commitments. If we insist on conflating ‘organisation’ and ‘enterprise’, we end up with a self-centred, self-referential entity disconnected from anything else in the real world – an all-too-common mess that typically takes a lot of effort to resolve.

5) (not present?)

6) On systems-theory, strong agree on “there are of course different kinds of systems”, all interweaving with each other. These are also systems-of-systems, often full ecosystems in their own right, always fully fractal, and always in context of larger-scope systems and smaller-scope sub-systems, with hard-systems interpretations, soft-systems interpretations, and everything in between. That complexity is what makes EA and the like so challenging, but also so interesting… 🙂

7) On boundaries, whilst, yes, I fully agree that we need some kind of boundaries upon which to base meaningful and useful models, I’m also quite adamant that any such boundaries are arbitrary – i.e. they are ‘the boundaries’ (of ‘the system’ or whatever) because we choose them to be ‘the boundaries’. So yes, a strong agree that Coase et al. can provide useful guidance for useful boundaries for some practical purposes. However, that should not and must not be the only source of boundaries for EA work etc. (That distinction might seem a bit subtle, but is utterly crucial – otherwise we would automatically fall into the often-disastrous trap of ‘something-centrism‘.) Boundaries can have huge impacts on what we can and can’t ‘see’ in a context – hence we need be very careful, very aware, and fully conscious, of the boundaries that we choose for our work.

Tom,

I’ve now read your reply three times – it’s terrific. And especially to grapple with “business meaning” (realizing that [business ~= (life)] in the context of “boundaries” and “identity” and “systems” is a great. OK, really gr8.

You’ve commented on the assumptions underlying microeconomics, and I note your reference elsewhere to the (mostly forgotten?) slogan such that “property is theft”. Whether one agrees or not, the point however is extremely important in terms of systems theory. So much spurious authority is sought based on the invocation of some “Writer” or “BOK”, without the acknowledgement that any body of knowledge will have assumptions. Microeconomics is not a closed system and is thus non-determinative. One has to at least assume property or maybe class struggle or possibly revelation in order to make a prediction (I’m reminded of Carl Sagan’s comment that if you really want to make a pie from scratch, you first have to invent the universe . . . ).

And aha! I did leave out No. 5.

TL;DR. Genug for now . . .

John

“So in this case, ‘Business-Architecture’, ‘Data-Architecture’ and ‘Applications-Architecture’ form the context for the services-in-focus here, the ‘Technology-Architecture’. If we want to focus on data-architecture, applications-architecture, or business-architecture, we need to find the respective broader-context for each of those, as the respective services-in-context”

Thanks posting this. I think this summarizes your key point why bdat / togaf is problematic. However, it would help clarify it for me and hopefully others if you describe what is the 1, 2 and 3 levels above in scope when data-architecture, application-architecture, and business architecture respectively are the “base” services in context. An simple example of each would really help drive home the point for me.

The answer is not exactly jumping out at me (maybe just because this is new to me…)

For example:

Service in Focus: Data Architecture

Transactional Context: ? Is this the question to ask – Who/what are the providers and consumers of data architecture?

Direct Context: ? Who are the competitors/regulators/market when data architecture is the service in focus?

Indirect context: ? ??

Service in Focus: Application Architecture

Transactional Context: ?

Direct Context: ?

Indirect context: ?

Service in Focus: Business Architecture

Transactional Context: ?

Direct Context: ?

Indirect context: ?