Methods for whole-enterprise architecture – Keep it simple

For a viable enterprise architecture [EA], now and into the future, we need frameworks, methods and tools that can support the EA discipline’s needs.

One crucial criterion is that any methods and frameworks we use must support fractality – the same patterns, regardless of scope or scale. If we keep the focus on the fractality, working with even the most complex of contexts can actually be quite simple.

An illustration of this came up in one of the comments on the worked-example for the series, where we used the methods to assess the applicability of so-called ‘Bimodal-IT’. The example showed how the methods made it feasible to assess, in just a couple of days, the core context for what would otherwise be a multi-million dollar decision. But because it would have been a multi-million decision, the description went into a fair bit of step-by-step detail.

The outcome of that post, though, was that the first commenter complained that it all seemed “too complicated” – which I’ll admit was a bit of a disappointment…

(I can only suspect that he’d never tried to use the full TOGAF ADM for any real-world enterprise-architecture? – the adjective ‘complicated’ most definitely does apply there…)

So to respond to that critique, let’s strip the suggested method right down to its barest essentials. The kind of architecture-method that, quite literally, we could use to assess a simple architectural context in mere minutes, yet still in a fully-disciplined way – and that’s exactly compatible and comparable with the method we might use for a multi-year programme of architectural change.

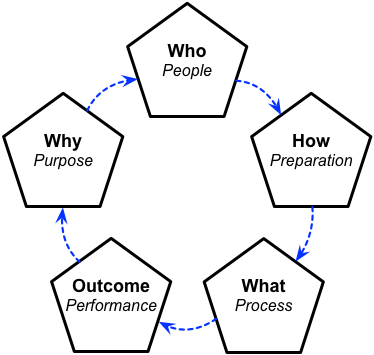

First, let’s see the method in its simplest possible form – a five-word action-checklist:

- Why? – what’s the reason for the doing the work? what’s the ontext for that question? how would we know when we’ve answered the question?

- Who? – who are the stakeholders in this question? who needs to be involved?

- How? – how are we going to address this question? what frameworks, models and methods should we use?

- What? – what happens, where, when and with-what, as we follow the plan to explore the question with those people? how do we know when to stop exploring, and settle out to an answer?

- Outcome? – what answer did we achieve? what did we learn from doing the work? how could we each do it better next time?

Just five words – Why? Who? How? What? Outcome? Over and over, fractally, indefinitely, in accordance with the Architect’s Mantra of ‘I don’t know‘, ‘It depends‘ and ‘Just enough detail‘ – the latter being perhaps the most important here.

That’s it, really.

Pretty simple.

But very practical.

Though if you want a bit more detail, as a set of step-by-step work-instructions, here it is:

— Why phase (‘Purpose’)

- Establish, clarify and refine the business-question for review

- Identify applicable scope

- Identify underlying vision, values and guiding-principles

- Identify success-criteria for this iteration

Notes: Why vision and values matter is that they provide guidance whenever we fall into the ‘Not-known’ – as we necessarily must, at times, if we’re exploring any unknown or new. We also need the same values and principles to guide the crucial situational-awareness loop, from commander’s intent to ‘fingertip feel’ of what’s happening in the respective real-world context, and back again. (See the post ‘Auftragstaktik and fingerspitzengefühl‘ for more on this.)

— Who phase (‘People’)

- Identify who is likely to have knowledge we need

- Identify stakeholders for the business-question, and their drivers

- Identify and assess any underlying politics…

Notes: How do we identify who the stakeholders are? A simple test is that a stakeholder is anyone who can wield a sharp-pointed stake in our direction… (Hint: there are a lot more of them than we might at first think…)

— How phase (‘Preparation’)

- Identify frames and methods that match criteria for the current business-question

- Create context-specific methods for action

- Build action-plan

Notes: The Start Anywhere principle is that since everything connects to everything else, and everything depends on everything else, that means that it doesn’t really matter where we start – we can start just about anywhere and still eventually arrive at the same place. For example, given the right toolkit, we could start from context, or services, or complexity, or capability and strategy, or service-content, or value-flows, or narrative and story, or effectiveness, or governance, or architecture-maturity, or whatever. In effect, ‘Where to start?’ doesn’t matter all that much – what does matter is that we do get started!

— What phase (‘Process’)

- Enact the action-plan

- Engage with stakeholders during the action

- Apply governance as needed for the context

- Capture architectural information as required

Notes: We continue working in this phase until we have ‘Just enough detail’, and/or we match up with the completion-criteria (‘success-criteria’) identified at the start of the iteration, in the Purpose/Why phase. Remember too that enterprise-architecture is not solution-architecture – they work with different requirements and deliver different outcomes and artefacts, and we need the right toolset for each type of work.

— Outcome phase (‘Performance’)

- Assess benefits-realised and value-delivered from the iteration, as per the success-criteria

- Assess lessons-learned from the iteration

- Set up for further actions

Notes: Don’t skimp on this phase! – it’s how we establish and prove that we’ve delivered real business-value, and how we build competence, expertise and maturity in enterprise-architecture.

Overall, use the cycle for any scope, any scale, any duration, any depth of detail, nested fractally to any depth… start a new nested iteration anywhere… – but always do the whole cycle (because if not, it will probably fail…).

There are very good reasons why we do the Five Elements cycle always in that sequence – don’t try to skip over or avoid any of the phases!

Again, that’s it, really: it’s not complex. And it needs to be that way: to tackle complexity, we need our methods to be simple – as simple as practicable, fully fractal, self-adjusting and self-adapting to every context. Which is what we have here.

Try it, anyway. And over to you for comments, perhaps?

Nothing temporal? Nothing time related? I’m thinking governance rollout. Like laws going into effect a few years fromantic concept. Brexit 2 year implementation. Social Security changes rolling out. A political platform for 4 years. Climate change deadline before extinction. Or is timing at a lower level?

Sorry…thinking about this with lack of sleep and no coffee. Dangerous combo.

Nothing temporal? Nothing time related? I’m thinking governance rollout. Like laws going into effect a few years from concept. Brexit 2 year implementation. Social Security changes rolling out. A political platform for 4 years. Climate change deadline before extinction. Or is timing at a lower level?

Sorry…thinking about this with lack of sleep and no coffee. And typing on a mobile phone. Dangerous combo.

All fair enough comments, Pat – by comparison with any of the mainstream ‘EA’-frameworks, anyway. And you’re right, time does need a mention in there, that it doesn’t have at present.

The key idea behind the method is that it is explicitly content-neutral. We then attach content, constraints, context-specific frameworks and suchlike to each iteration in a conscious way, rather than as all-too-often-unconscious assumptions. That’s the only way in which it can be usable in a truly fractal way.

My probable mistake here was to not be explicit enough that all those other factors (such as time etc) need to be included into each iteration in a conscious and deliberate way: that although they’re not built-in to the method, they cannot be ignored, and must be included. At present it’s sort-of implicit in the use of a Zachman-like content-checklist in the Preparation/How phase, and inclusion of Where and When as sub-emphases of the Process/What phase, but yes it needs further clarification.

From what you and others have said, it looks like I’ve swung the pendulum a bit too far away from Zachman/TOGAF over-complication, into somewhat too much of an over-simplification. More work to do, then, to bring it back to a more right-balanced position. Oh well. But I hope it’s a useful start, anyway?

Hi Tom,

Many thanks for your speech @Arismore last week.

You show us feverishly the forms of your method. Are they free to use ? And, if so, could you provide me a pointer for downloading them ?.

KR

Hi Pierre – sure, they’re free to use (Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike). I’m keeping them a bit quiet at the moment because I need to produce better materials to go with them, but Jean-Baptiste has a copy of the file, and the whole idea is that he’ll share them around your team. I’ll also send him a link to the main slidedeck I showed, and also the intro-slidedeck for the workshop part. (You may have to wait around until he gets back from ‘ses vacances’ 🙂 – though I believe he’ll be back on Monday?)

I also found (at the Pompidou, no less!) a French translation of that book I mentioned, Matthew Frederick’s ‘101 Things I Learnt In Architecture School’. I bought a copy for you to share around – it’s with Axel Hurgon at the moment, I think.

I’ll keep in touch with you all, anyway.