Service, product and architecture terminology

This one’s a follow-on to the ‘Service, product, service‘ post, but with an emphasis on the role of architecture-terminology itself, rather than any specific item referred to by that terminology.

This starts with a private LinkedIn-message that a colleague sent to me after that previous post (though since there’s a risk that this will devolve into something of an angry rant, I won’t say who that person was). The core of the message was this:

Read this blog [the ‘Service, product, service’ post].

Prior to reading the above post, I thought products as “offering(s)” of services and/or goods to consumers from an economic theory perspective.

Your thoughts.

Yep, from “an economic theory perspective“, that definition above seems fair enough. But is that the only possible perspective? Are there other perspectives that might apply here? Hmm…

(I did warn that this might devolve into a rant. Yes, it is going to be that way. Sorry…)

The main focus of this blog is about architectures and the like at the enterprise scope and scale, and methods and taxonomies and terminologies and suchlike that might help support those needs. Yes, I do occasionally touch on economics, though mainly in response to the utter inanities, in architectural terms, that still predominate in that space.

Other than that, this isn’t a weblog on mainstream economics – perhaps especially not at the microeconomics level of pricing and offerings as such. For the ‘Service, product, service’ post, there should have been a fair clue about this focus, just in the header that was attached to the posting there:

In a service-oriented architecture [emphasis added], a ‘product’ is a ‘frozen service’ – an asset that triggers a service to use itself at some time elsewhere or elsewhen.

Again, “in a service-oriented architecture“. Not “an economic theory perspective”. That distinction is clear, I hope?

But in which case, why focus on architecture? Why not let economics be the centre of everything? After all, isn’t that what just about everyone else does, in business and elsewhere…?

To me, the role of architecture is to link everything together. Our task is to ensure that things work better when they work together, on purpose.

Which means that we need to be able to link anything with everything else. Any content, any context, every scope, every scale, everything, everywhere.

Which in turn means that everything and nothing is ‘the centre’ of the architecture, all at the same time.

Which in turn means that, for a viable architecture of any kind, we cannot allow anything to be ‘the sole The Centre Of All Architecture’. In architecture and beyond, there are very real dangers of ‘anything-centrism’: hence why, if you’ve read this blog a while, you’ll have often seen me rant about IT-centrism, business-centrism, ideology-centrism, and just about any other kind of ‘my-piddling-little-part-of-the-architecture-is-the-only-bit-that-matters-ism’. Whatever the architecture, any kind of ‘anything-centrism’ always kills the viability of that architecture, every time: it is definitely Not A Good Idea…

Which, yes, means that, for architecture, we need a taxonomy and terminology that actively mitigates against that architecturally-lethal mistake. That actively aids us in translating between all of those myriad little would-be-the-centre-of-everything perspectives, and actually helps us in cleaning up the goddam mess that most people seem to make around even the basic of terminologies. (‘Business Process’ versus ‘Business Service’ versus ‘Business Function’ versus ‘Business Capability’ versus ‘Business Unit’, anyone? Across any two companies, or even any two business-units? Yeah, it’s a shambles. Sigh.)

So, back to ‘product‘: what the heck is ‘a product’? Well, it depends…

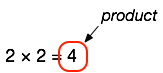

Here’s a product:

…used in a service (the services of a cafe kitchen) to create another product (a meal on a plate) for another (self)-service (eating the meal):

…which, yes, most of which matches up quite well with that “economic theory perspective”. Fair enough.

Yet if we look around a bit, we’ll see that this too is described as a product:

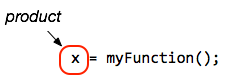

…as is this:

…which, respectively, are the outputs (‘products’) of the ‘multiply’ service and ‘myFunction’ service. And yes, from an architectural perspective, those are every bit as much ‘products’ as the mostly-physical, commercially-saleable ‘things’ that are the only type of ‘product’ that the ‘economic theory perspective’ would recognise.

And those ‘products’ of arithmetic or code might well also play a key role in some other aspect of the ‘economic theory perspective’ – such as, in this case, the bill for the delivery of the meal and the products that went into it. Even though the bill itself isn’t something that we’d pay for – as a client of the ‘cafe-meal service’, anyway. If we’re not careful, this can get real complicated, real quick… – especially in contexts where we might need to substitute one type of service or product for another (‘fungibility‘), and especially if we use randomly-different terms from different perspectives for what are, architecturally-speaking, actually the same kinds of things.

In which case, what terminology can we use such that we can make sense in the same way about all types of ‘product’ in an architecture, across every type of content, in every context, every scope, every scale, every level of abstraction / realisation, everywhere? What could we use to help translate between the myriad of context-specific meanings across all aspects of that architecture-space? Here’s how I would approach that question:

— First, avoid any hint of ‘anything-centrism’. If we fail on that one, we’d fail right at the first step.

— Then, declare the assumptions that will and must apply to the perceived or presumed overall context-space for the terminology. (See my post ‘Declaring the assumptions‘ for more on that.)

— Next, go back to the generic root-level concern – that which is the same in all contexts, regardless of surface-appearance, perspective or whatever. Which in this case is about the distinctions between actions on something (CRUD and all that), the ‘something’ that is acted on, and an indication and identifier for that ‘something’ when it is not being acted-on.

— Then, find a generic root-level term those natural-meaning matches up with those root-level distinctions. In this case, we derive ‘service‘ (‘that which serves’) as a term for the ‘actions on something’; ‘asset‘ (‘thing with associated responsibilities’) for the ‘something’; and ‘product‘ (literally, ‘onward-leading’) for that identifiable intermediate-state for the ‘something’.

— From there, using the same principles and process, derive a context-independent taxonomy and terminology, interlocked, interrelated and consistent across all possible context-independent terms as per above – or as much as practicable for that context-space, anyway. (See my post ‘Fractals, naming and enterprise-architecture‘ for more on that.)

— Given that context-independent terminology as a common reference-base, do context-specific translations between contexts and perspectives, as required.

(Without that context-neutral base, the only option we have is point-to-point translations not only between types of contexts (such as finance to/from IT), but also context-specific ‘languages‘ (such as different terminologies or frameworks in the supposedly same IT space). Now multiply that requirement for point-to-point translations not just between any two points, but between every point across every context, every domain, every different level of abstraction, every different level of granularity. Without a common reference-base, that’s not only a guaranteed recipe for major headaches and nightmares, it’s a guaranteed recipe for miscommunication, screw-ups, and failures right up to Mars Climate Orbiter level and beyond. Not A Good Idea…)

So, to bring all of this back to the initial question, about the ‘economics theory perspective’ of “products as ‘offerings’ of services or goods”, what does all of this tell us?

First, as in that example, we’ll often find terms being randomly used as synonyms for each other, the same term used to describe different things, different terms being used to describe the same thing. A service is a product, which itself can also be a service. Or a product. Or a ‘goods’ – whatever that might variously be defined to be. When one kind of ‘thing’ is defined as something else, which in turn is defined as itself and something else as well, what chance in hell do we have of making any sense of that? – other than as a random-guess-and-hope-for-the-best?

Sure, the terminology from ‘the economics theory perspective’ might perhaps make some sense to those who are familiar with ‘the economic theory perspective’ – though the scrambled terminology is itself likely to cause confusions every step of the way even there. But to connect it to anyone else’s terminology, any other discipline’s terminology, any other of the myriad of other perspectives? – not a chance.

And let’s throw in another lovely little nightmare into this mess: the issue of boundaries.

The reality is that almost every boundary is arbitrary. Take a look:

— What’s the boundary of a service? – the short-answer is “Wherever we choose to say it is”.

— What’s the boundary of a process? – short answer: where we say it is.

— What’s the boundary of a change-project? – short-answer: where we say it is.

— Where’s the boundary of a software system? – short-answer: where we say it is.

— What’s the boundary of a database? – short-answer: where we say it is.

— What’s the boundary of an enterprise? – short-answer: where we say it is.

— What’s the boundary of a product? – short-answer: where we say it is.

Example after example after example – always with the same short-answer. And it always depends on view and viewpoint: all of which are also where we say each is.

The boundaries that we currently choose, they in turn give us our ‘perspectives’: any number of them. Any number of them. Each of them often with their own distinct terminology. Which terminology can itself change almost at random at almost any time, along with the respective boundaries that define the applicable scope for that terminology.

Oh boy…

Which, yeah, is why I rant about this stuff. If you only stick in one domain, one organisation, one level of abstraction, then yeah, it’s probably not a problem. Not much of a problem, anyway. Though if you only stick to one domain, one organisation, one level of abstraction, then almost by definition you’re not dealing with architecture. Not much. Not really, anyway.

But the moment you have to communicate with anyone else, yeah, it becomes a problem all right. And in most cases I know, architects have to be able to communicate with everyone, across all of their respective context. So yeah, this terminology-problem that doesn’t look like much of a terminology-problem to most people we deal with is actually a huge problem for us. Huge.

So yes, there are a myriad of ever-changing perspectives, each with their own ever-changing terminologies. And as architects, we’re supposed – required – to sort out the resultant mess. Because getting people to talk with each other, connect things together across all of those arbitrary boundaries, those different perspectives, well, that’s how we get things to work better, together, on purpose, and all that.

Agreed, as architects, we do need to know all of those different terminologies – or enough of them to get by, at any rate. Hence, yes, I do know the ‘economics theory perspective’ of product as ‘an offering’ or whatever. Yes I do know that it’s often a valid perspective for many kinds of architecture – but so is every other perspective. And the moment we allow ourselves to fall for any kind of ‘anything-centrism’, the moment we arbitrarily privilege any one of those perspectives above all others – the IT-centric perspective, the ‘economics theory perspective’, the our-tribe-is-more-important-than-everyone-else perspective – well, that’s when we’d be setting ourselves up for failure, for a failed architecture that can’t service the required needs. Not A Good Idea…

Instead, find a common-core terminology that helps make sense across all terminologies – not least by focusing first on the core underlying concept rather than the surface label, the surface appearance, the current surface-level boundaries. Once we do have that common core, we then have some chance of sorting out the mess, of staying sane – or somewhat sane, at any rate – amidst the turgid, turbulent, twisting, turning tangles of ever-changing terminologies. But without it? – no chance. No chance at all.

That’s the choice, really.

Best leave it that for now? – though over to you for comment, of course, if you wish.

Leave a Reply