Context-space mapping with Enterprise Canvas, Part 3: Value-proposition

So far in this series we’ve explored enterprise-vision (Enterprise Canvas row-0) and high-level business-context (row-1) in a fairly straightforward way. It’s been much the same as any other conventional ‘top-down’ strategy-development, except that we haven’t really mentioned our own organisation at all as yet. (That’s coming shortly. 🙂 )

A few important points have come up in the comments to those two articles, though, which are worth reiterating here before we move on.

One is to remember why we’re doing all of this. It’s not about abstract ‘blue-sky’ thinking: it’s about building a stable platform for organisational change. In enterprise-architecture, this needs to be a platform in which all of the other architectures – business-architecture, process-architecture, skills-architecture, values-architecture, security-architecture and, oh yes, all the IT-architectures too – can all interweave and interlink and intermesh into a single unified, dynamic whole. But although we talk a lot about the extended-enterprise here – especially in these ‘higher’ layers – this isn’t actually for anyone else at all: unless someone seriously-senior decides otherwise, all of this is solely for our own organisation (or client, if we’re doing this work as external-consultants). Working this way, whatever we develop is always in the context of this broader extended-enterprise: but our own organisation (or client) becomes more and more the centre of our attention as we move down the layers. That transition of emphasis starts to happen here. In short:

In enterprise-architecture, we create an architecture about an enterprise, but for an organisation.

It’s really important to remember that point – not least because it’s the organisation, not the extended-enterprise, that’s paying our bills! 🙂

Another point that came up in the comments is that the usual nine-cell structure of the Enterprise Canvas can be a bit misleading in these upper levels. The nine-cell structure is really a kind of functional-decomposition – who’s handling what interfaces, and why. But functional-decomposition assumes or describes specific interfaces and relationships – and we haven’t even got that far yet. In row-0 and row-1 we only deal with each entity as a whole, without any internal subdivision into cells. It’s only here, in row-2, that we start to introduce the idea of relationships and roles between entities, which eventually leads us to relationships and roles within entities, which leads us in turn to that nine-cell structure. If you try to use the nine-cell structure in rows 0 or 1, or in most of the work in row-2, you may have missed the point somewhere: at those levels, it’s only about each entity as a whole.

And finally, I would hope that by now you’ll have realised that this can be a lot harder to do than it might seem at first glance. It’s so easy to fall back to organisation-centric habits, where the organisation is placed as the sole centre of everything. The blunt fact is that it isn’t that ‘sole centre’ at all: in fact, the organisation only has a reason to exist if it’s placed within the context of its extended-enterprise. If we don’t understand that broader context, we would have nothing to guide us when that context changes – which, these days, can happen on a literally moment-by-moment basis. One of the keys here is that the description of that enterprise is literally emotive – it drives change. So although a lot of thinking and analysis will be needed here, ultimately it’s not a rational matter – it’s about what feels ‘right’, about identifying what is valued. This is especially true of the vision-descriptor: we need to keep exploring that context-space until we hit upon a phrase that can engender emotions and commitment that are literally strong enough to get people out of bed in the morning.

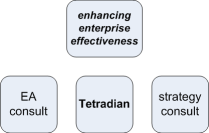

Anyway, time to move on: time to start looking at the business of the enterprise, and of the organisation itself. To summarise where we’ve gotten to so far with this example, we’d established a row-0 ‘Enterprise’:

We then started a Zachman-style row-1 ‘Context’ with a conventional market-based view of our enterprise, with our own organisation as its centre:

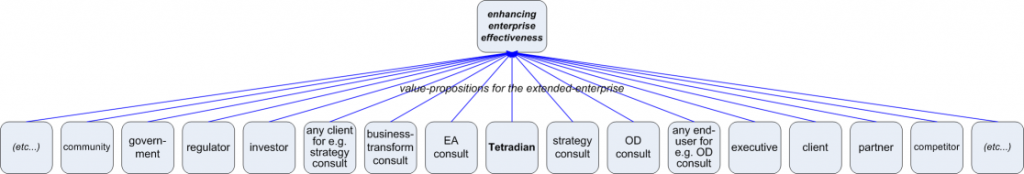

Which didn’t show us many options. But as we started to explore what that enterprise-vision meant in practice, and what kinds of stakeholders would be engaged in that vision, we realised that the actual enterprise was much broader than our current market:

Which should create many more strategic opportunities than we were able to see before. To make this work, though, we first need look more closely at the meaning of a common business-term: value-proposition.

Rethinking the value-proposition

In much of the conventional business-literature the term ‘value’ is linked indivisibly with price, or even equated with price. This is certainly the view associated with neoclassical economics, currently the dominant paradigm in most mainstream economic thinking. (If it can be called ‘thinking’: a more accurate term would probably be ‘superstition’ or, more literally, ‘cargo cult‘. My opinion, for what it’s worth, is that I’m continually astounded by the gaping flaws in both observation and reasoning in most so-called economics: the flaws in key concepts such as ‘rational-actor theory‘ are so blatant and so fundamental that I still find it almost impossible to understand how nominally-sane, nominally-intelligent beings can take those concepts seriously at all. But I digress…)

We also see other value-laden terms – ‘value’ in a somewhat different, broader sense – in the idea of ‘value-proposition as a means of positioning a product or service relatives to those provided by direct or indirect competitors: for example, the product is purported to be cheaper, cleaner, easier to use, more ‘green’, more ‘exclusive’, and so on. That type of modelling and comparison does become relevant when we get down to the fine-detail of business-models and the like in row-3 ‘System’ and, far more, in row-4 ‘Design’. But here, in row-2 ‘Business’ and above, there is a much simpler definition of value:

Value is whatever the enterprise-vision says it is.

The enterprise-vision – and particular the Qualifier in the vision-phrase – defines what is most valued in and by the extended-enterprise. In effect, it’s a condition of membership of the enterprise that the respective value or values are assigned to a high or even highest priority by each player in the enterprise.

The enterprise-values are not always assigned the highest priority, by the way, for the simple reason that every person and organisation exists within multiple enterprises – the enterprise of professional discipline, a family, a community, a country, humanity as a whole, and so on. Technically speaking, an enterprise is a ‘system’: every system – every enterprise – is contained in and intersects with other systems. The enterprise in scope that we’re exploring here is the one that’s of primary business-interest to our organisation – the enterprise about which we’re building an architecture for this organisation – but it’s essential to remember that it’s not the only enterprise that exists.

As part of their membership of the extended-enterprise, each player in the enterprise commits to delivering some kind of value to that extended-enterprise. In the context of this layer (row-2 ‘Business’ and above), the value-proposition is the value that the entity may and can bring to the shared-enterprise. In effect, the value-proposition is the choice of value to deliver, the ability to deliver that value, and the commitment to deliver that value.

Which brings us back to some of the questions with which we started this series: What can I/we do that creates value? Where could I/we add value? What role could I/we play within this enterprise? What capabilities (and hence, when linked with a role, ‘missions’) could I/we bring to make this enterprise happen? Who do I/we need to work with to make this happen?

There’s an important recap we need to do here, though. The enterprise-vision is energising, literally emotive, a literal driver for action. If we feel committed to that enterprise, yet have no apparent value to bring to the party, we perhaps need to do some deeper exploration – which we’ll tackle here shortly. But if we try to force-fit our skills and so on to an enterprise to which we don’t feel that same emotive commitment, the amount of value that we can add will be much less: being in the ‘wrong’ enterprise is literally ‘de-motivating’, certainly passively so, and often actively, and always reduces effectiveness for all parties involved. (This is true for all types of work, but especially so for knowledge-work or decision-work, as Daniel Pink explains well in his book ‘Drive‘.) This is a major reason why Taylorism and monetarist-economics are so ineffective in practice: they force just about everyone to be in the ‘wrong’ enterprise. It’s something we need to watch for, very carefully, if we want our organisations and our own work to be effective, valuable and valued.

The same questions apply to every player in the enterprise: What is their value-proposition? What can they do to make the vision come to life in the real world? That’s the nature of an ecosystem: in principle at least, everyone brings something to the party:

This delineates each party’s role relative to the enterprise – the ‘vertical’ dimension for each Enterprise Canvas element, the commitment to create value in the enterprise.

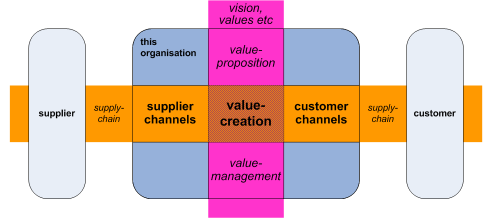

Their roles relative to each other within the enterprise – the ways in which value moves around within the enterprise – provides the ‘horizontal’ dimension for the Enterprise Canvas element:

In effect, the linkages in that horizontal dimension represent the value-propositions we have for each other within the enterprise. A couple of layers further down towards implementation, this leads us to the kind of value-proposition that would typically underpin a conventional business-model – better, cheaper, faster and so on – but we need to remember that all of that actually comes from here: the value we offer to the enterprise as a whole, and the dynamic flow of value around the enterprise that brings the enterprise-vision to fruition.

Value-relationships

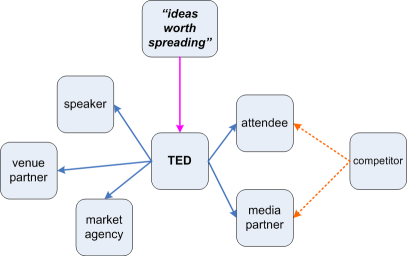

Looking at these ‘horizontal’ relationships is what brings us ‘downward’ to row-2 (‘Business’) in the layering of the Enterprise Canvas. For example, there’s the (very simplified!) example row-2 diagram for the TED Conferences shared-enterprise, from the ‘Layers‘ article in the initial Enterprise Canvas series:

This is also the first point at which we need to start thinking in depth about our own organisation, as an entity in its own right rather than solely in terms of an extended-enterprise. Whilst still keeping the extended-enterprise as a whole in mind, we need here to be ‘self-centric’ for a while:

- What value could I/we add to the extended-enterprise? – our value-proposition to the whole, the reason we are here?

- Which other players need the value we create for the enterprise in order to create their value for the enterprise? – who are our customers?

- What value (such as in the form of products or services) do we need from other players in order to create that value? – who are our suppliers?

- Which other players deliver complementary value to the extended-enterprise? – who are our partners?

- Which other players deliver the same value to the extended-enterprise? – who are our competitors?

- Which other players will support us to get started (or continue) to deliver value to the enterprise? – who are our investors?

- Which other players will we support whilst delivering value to the enterprise? – who are our beneficiaries?

And we also need to look at this in terms of the extended-enterprise as a whole:

- Which other players help to keep the overall value-web moving? – who are the coordinators, the suppliers of ‘coordination-services’?

- Which other players help to identify direction of the overall enterprise? – who are the futurists and/or historians, the suppliers of ‘direction-services’?

- Which other players will help to keep us on-track to the vision and values of the enterprise? – who are the regulators, the suppliers of ‘validation-services’?

Each of these relationships implies a value-proposition of some kind – a mutual value-proposition, since the aim is that value will be exchanged between the parties. The most problematic relationship, of course, is that of ‘competitor’: whenever we have two or more players purporting to deliver the exact same value, this implies – and potentially creates – ineffectiveness within the overall extended-enterprise. Sometimes there is genuine value in such ‘competition’: for example, redundant-duplication also supports resilience, in reducing the risk associated with any single point of failure. Constructive ‘competition-with‘ also helps to drive innovation and creativity to push the overall enterprise forward towards its vision. Destructive ‘competition-against‘, though, is something we do need to avoid, for everyone’s sake. Techniques such as Blue Ocean Strategy can help a lot here: what we need to look for is a niche that fits well with our own competencies and capabilities, fits well with our sense of the enterprise as a whole, and which complements rather than competes directly with anyone else in the shared-enterprise.

Note that although we’re starting to get closer here to conventional strategy-development and business-model development, we’re still not there yet: in fact the proper ‘business-models’ and the like don’t properly begin to emerge until down in the next layer, row-3 ‘System’. What we really look at here is just one question:

- Given each player’s value-proposition in the overall extended-enterprise, what would that imply in their relationship with us?

Or, to put it the other way round:

- Given our own value-proposition in the extended-enterprise, what relationships with us would that suggest to others?

The answers to either version of that question provide the prototype for our organisation’s business-models. And importantly, by the value-driven nature of those relationships, that would be a self-marketing ‘pull’-type business-model – a huge advantage over the conventional ‘push’-type marketing-model, where the absence of any self-evident reason to relate forces us to manufacture a sort-of-relationship from nothing.

So to apply all of this for our main example here, my own enterprise-architecture consulting-business:

- What is the vision for the overall extended-enterprise? – “enhancing enterprise effectiveness”

- What are the key values here? – examples include the five dimensions of effectiveness – efficiency, reliability, elegance (in the generic sense), appropriacy, integration – and direct derivatives or compounds such as resilience, simplicity and integrity

- What is our own value-proposition to the extended-enterprise? – we provide tools, techniques, training and insight on enterprise-effectiveness, particularly in whole-of-enterprise architectures (the intersection of structure and purpose) and whole-of-enterprise integration (processes, practices, metrics and people-related themes)

- Who would value our value-proposition? – in principle, anyone doing the practice of enhancing effectiveness within organisations

That last line tells us our nominal customer-base, which is huge: in principle, it applies to just about any organisation anywhere in the world. Too large to be practical, in fact – which is a serious problem for us. As futurists and developers of new techniques, the work we do is often a long way ‘ahead’ of the mainstream: our main customers at present tend to be early-adopters or very-early-adopters, but in almost any industry. This means that our current market is very broad but very ‘lumpy’ (“the future is already here, it’s just that it’s not evenly distributed”, as one science-fiction writer put it), so we’re faced with a classic dilemma: do we spread the net wide but risk being too generic to be much use, or limit it to a narrow domain which has a more explicit practical focus but for which there are too few early-adopters to make it viable? Getting the right balance here is going to be crucial to success.

- What products, services and other value do we need from other players? – our ‘product’ is ideas and techniques, hence anything that feeds into that, such as information, practices, test-cases and peer-review

Although this is fairly typical for a professional-services firm with a strong research-and-development focus, it demands radically different relationships from those of, say, a retail outlet or a utilities corporation. In the latter, there are clear distinctions between ‘customer’ and ‘supplier’, and hence (usually) clear boundaries between the respective relationships; whereas in this case, every customer is also a ‘supplier’ in that each context will have always have some aspects that are new and unique, and hence provide us new information, new test-cases and new peer-review. The same applies to our partners and even to our nominal ‘competitors’: we each become most effective when we each provide peer-review for each other. Conventional near-combative relationships based on ‘competition-against’ and proprietary notions of ‘intellectual property’ will guarantee failure here, for everyone: yet we also need to protect ourselves – and everyone else in our enterprise – from predatory types who unfortunately do believe that aggression leads to ‘success’. The key here is to leverage off the enterprise-vision and values: we need to assess all potential relationships – customer, supplier, partner, even ‘competitor’ – against that yardstick of shared overall effectiveness.

- Which other players deliver complementary value to the extended-enterprise? – anyone working on enhancing enterprise effectiveness in organisations, particularly those people or groups working in more specialist domains such as organisational-development, process-improvement, knowledge-management, quality-management, skills-architectures and the like

This again is a huge ‘market’ – and hence again a real risk of spreading ourselves too wide and too thin. The key point is that our emphasis on whole-of-enterprise architectures is a generalist domain, whereas most of these potential partners are specialists. So there’s no ‘competition’ as such: what we look for are synergies, to cross-leverage each others’ work. Building appropriate relationships here would be fundamental to our marketing. One of our key value-points is that as generalists we provide a means to cross-link between the specialist domains; we and our colleagues will often act as facilitators, arbitrators and ‘thought-translators‘ to reduce the risk of getting lost in translation between domains.

- Which other players deliver the same value to the extended-enterprise? – the ‘product’ is ourselves, so there are no direct competitors as such: the real ‘competition’ here is not so much for market-share as mind-share

Our greatest ‘competitive’ problem at present is misuse and misappropriation of key terms by others, which can make it almost impossible to communicate what it is that we do, and the value that we deliver. Perhaps the most important of these are the near-ubiquitous misuse of the terms ‘enterprise’ and ‘enterprise-architecture’, and thence also ‘business-architecture’. It seems that most business-people fail to understand the difference between ‘the organisation’ and ‘the enterprise’ – hence why so many references in these articles to ‘extended-enterprise’, to try to establish those crucial distinctions. And it certainly seems true that very few IT-folks seem able to grasp that serious problems can arise from conflating the term ‘enterprise-wide IT-architecture’ into ‘enterprise-architecture’: in the former, the IT-architecture has an enterprise-wide scope, whereas in the latter the enterprise is the scope. One result of such IT-centrism is that ‘business-architecture’ is often taken to mean ‘anything not-IT that might affect IT’, leaving no space to describe anything which is mostly or entirely outside of the scope of IT.

In our work, we struggle every day with the consequences of these fundamental terminology-mistakes: although there are some signs of change (such as the Open Group‘s dawning awareness that enterprise-architecture must extend beyond the ‘comfort-zone’ of IT), it seems likely that this ‘mind-share problem’ will remain with us for at least another decade or more. In the meantime, just about all we can do is, again, point to the enterprise-values, demonstrate that IT-centrism, business-centrism and the like are in direct breach of most of the ‘effectiveness’ themes – particularly ‘integration’ – and explain quietly what to do to repair the damage. Frustrating, but that’s what happens when mind-share is dominated by major misunderstandings about the nature of the extended-enterprise itself, and by mistaken, much-mangled terminology.

- Which other players will support us to get started (or continue) to deliver value to the enterprise? – our ‘investors’ are mostly ourselves, though we need to remember that many others (especially our partners) invest ideas and personal and/or professional support in what we do

- Which other players will we support whilst delivering value to the enterprise? – our key ‘beneficiaries’, again, are ourselves, though it’s extremely important to us that we also contribute to our partners’ development and to the development of the enterprise as a whole

And, in terms of the extended-enterprise as a whole:

- Which other players help to keep the overall value-web moving? – the short answer is ‘not many’: there’s a real dearth of ‘coordination-services’ across this enterprise, and a real need for an equivalent of the services that SourceForge, for example, provides to Open-Source collaboration

- Which other players help to identify direction of the overall enterprise? – other than our partners, ourselves and some futurist organisations, there don’t seem to be many working in this space: most of the industry-bodies such as Open Group focus solely on subsets such as IT, rather than on the extended-enterprise as a whole

- Which other players will help to keep us on-track to the vision and values of the enterprise? – again, there don’t seem to be any real providers of ‘validation-services’ here: there’s a real need for this

The other key point to note here is that we need to remember to keep in mind that all of the players in the extended-enterprise could play any of these roles, relative to each other, or relative to us – and likewise we to them. This awareness becomes extremely valuable whenever we need to rethink our current positioning or current market, because it greatly increases our options relative to most conventional approach to business-strategy or business-development.

Another example

We could also apply all of the above to the example provided by Pat Ferdinandi in the comments to the previous articles, a real chain of restaurants in the US called Elevation Burger. Using quotes from their website (in double-quotes below), our assessment at this whole-of-enterprise layers of the Enterprise Canvas might go like this:

- What is the vision for the overall extended-enterprise? – tag-line “ingredients matter”, implying an enterprise-vision of something like ‘making food that matters’ or ‘making food matter’

Note that the ‘vision’ on the website is a fairly standard organisation-centric marketing-style vision. It tells us quite a bit about the values and decisions made by the organisation: “a vision for an elevated product that is fresh and flavorful… for authentic, sustainably prepared food… for an elevated experience in a well-appointed and environmentally friendly setting”. But it tells us very little about the extended-enterprise in which the organisation operates – and that’s what we would need to know if we were to be trying to re-think the organisation and its relationships when the market context changes. In essence, what we have here in Enterprise Canvas terms is a (very good) example of a set of drivers at the row-3 ‘System’ layer – which is fine if we’re only refining our marketing based on the current business-model, but not much use if we need to rethink the business-model itself.

- What are the key values here? – examples include “quality ingredients”, “better for you”, “better for the environment”, “passion for good food”, “enthusiasm, drive and passion”, “bright, sincere, engaging and energetic”, “genuine enjoyment in serving others”

There are other values or emphases listed on the website, such as “organic, grass-fed, free-range”, but to me these are more likely to be detail-layer decisions – down at row-3 ‘System’ or even row-4 ‘Design’ – that express beliefs or instantiations around the more core values such as “quality ingredients, better for you, better for the environment”.

- What is the value-proposition that Elevation Burger offers to the extended-enterprise? – the company and its franchisees express the vision of ‘making food that matters’ via provision of burgers, fries, shakes, malts and cookies in a “well-appointed and environmentally friendly setting”, mainly in cities and larger towns in the US

In other words, this is the chosen role that the organisation will play in the extended-enterprise

- Who would value this value-proposition? – anyone wishing to eat ‘food that matters’, those suppliers who would provide such ‘ingredients that matter’, anyone who holds similar beliefs, anyone who would like to be a customer but is not yet resident or visiting any locations at which the organisation operates, potential franchisees (primarily those who hold similar beliefs), food-critics and other media representatives, environmental activists, restaurant-builders and other ancillary-service providers, local government, regulatory authorities and many others

- What value do Elevation Burger add to the extended-enterprise? – the organisation provides a practical instantiation of the enterprise-vision and values, via operation of restaurants that express those values

- Which other players are ‘customers’ who need the value that Elevation Burger create for the enterprise? – those who wish to eat ‘food that matters’ of the types that Elevation Burger offer (e.g. burgers, fries etc), and who place value on the food and the context in which that food is provided (e.g. “well appointed environmentally friendly setting”, via “genuine enjoyment in serving others”

- What value (such as in the form of products or services) do Elevation Burger need from other ‘supplier’ players in order to create that value? – providers of ‘ingredients that matter’ (meat, salads, bread, potatoes, milk, drinks, etc), providers of construction-services (e.g. “well appointed environmentally friendly setting”), real-estate services, marketing services (websites, advertising, flyers etc), logistics services, management and accounting services, etc, all of whom need to align with the enterprise-vision and values

- Which other players are ‘partners’ for Elevation Burger, who deliver complementary value to the extended-enterprise? – other restaurants who likewise commit to the tag-line “ingredients matter”, but who provide different types of food, such as pasta/pizza, fish, Asian-style, French/European-style, bakery etc

- Which other players are ‘competitors’ who deliver the same value to the extended-enterprise? – Elevation Burger claims there are none, at least on the US Eastern seaboard: “our founder couldn’t find the burger he had been dreaming of since he left California in 1999”

Note that although fast-food burger chains such as McDonalds or Hungry-Jacks/Burger-King might in principle seem to be direct commercial competitors, in practice they operate in a different market-segment – a different enterprise – in which price has a higher priority relative to “ingredients matter”. Or, to put it the other way round, Elevation Burger’s clientele would place a higher priority (and premium) on taste, environmental history, restaurant ambience and so on. The competition is therefore indirect (a comparison of somewhat-different extended-enterprises and enterprise-visions) rather than direct (a comparison of near-identical services and values). However, if McDonalds or the others choose (or are pressured) to re-emphasise their positioning on ingredient-quality relative to price, they might move more into the same enterprise-space. Clarity on enterprise-vision would help to mitigate this risk by creating more of a ‘pull’-orientation rather than the fast-food chains’ ‘push’.

- Which other players are ‘investors’ who will support Elevation Burger to get started (or continue) to deliver value to the enterprise? – management, direct financial-investors, franchisees, all employees and other staff, local communities, any of the ‘partner’ and/or ‘supplier’ and/or ‘customer’ groups

- Which other players are ‘beneficiaries’ whom Elevation Burger will support whilst delivering value to the enterprise? – any or all of the ‘investors’, also (in non-monetary values) farmers and other suppliers, community and environment

And we also need to look at this in terms of the extended-enterprise as a whole:

- Which other players are the coordinators, the suppliers of ‘coordination-services’ that help to keep the overall value-web moving? – examples include logistics, event- or media-organisers for shared-marketing across the extended-enterprise, collective sourcing for ‘ingredients that matter’, support-groups for organic-farming and for environmentally-friendly building etc

- Which other players are the futurists, the suppliers of ‘direction-services’ that help to identify direction of the overall enterprise? – examples include the Slow Food movement, food-critics and other writers on food, sustainability and/or urban renewal, futurists on sustainability, agriculture, food and health etc

- Which other players are the regulators, the suppliers of ‘validation-services’ will help to keep everyone on-track to the vision and values of the enterprise? – examples include support-groups for organic-farming and for environmentally-friendly building etc, certification-bodies for same plus sustainability etc

The important point in this last section is that all of the individuals or groups listed there are potential allies – and, importantly, any challenge from any of them should be regarded as a spur to action rather than as an ‘attack’, because their role is to remind Elevation Burger how to keep on-track to their own commitment to the extended-enterprise.

I’d better stop there – this has been more than long enough already! 🙂 More to follow, anyway, including a look at how to re-leverage assets and capabilities that we already have, in order to support a new strategy or business-model.

Leave a Reply