Rethinking the layers in enterprise-architecture

Still plodding away on ideas for a systematic process to translate a business-model in Business Model Canvas down into real-world architecture and implementation. (This links up with quite a few previous posts, such as ‘More on business-models‘, ‘Enterprise-architecture – let’s keep it simple‘ and ‘Is Archimate too IT-centric for enterprise-architecture?‘)

[Note: this is a work-in-progress post, not a finished piece – I really do need discussion on this one!]

What’s come up this time is the usual struggle with the so-called ‘architectural layers’ in common EA frameworks such as TOGAF and Archimate:

- Business

- Applications (in Archimate) or Information Systems (in TOGAF)

- Infrastructure

The problem is that, for me, these are ridiculously incomplete, and lead directly to IT-centrism – where IT is deemed to be the sole centre and basis for everything. That IT-centrism what creates most of the much-lamented ‘business/IT-divide’.

The corollary is that, because IT is placed as the centre for everything, and applications only run on IT, everything else has to be lumped into ‘business-architecture’, because it’s the only place it can go. Hence in TOGAF, for example, high-level business-strategy is bundled together with mid-level process and detail-level manual work-instruction, without any kind of distinctions between them, solely because it’s ‘not-IT’. And technology and infrastructure that isn’t computer-based – lorries, fork-lift trucks, assembly-lines, plumbing and wiring and even the buildings within which everything operates – don’t even get a mention anywhere.

This brings serious problems even in IT-specific architectures: for example, how can we usefully describe the overall architecture of a data-centre without mentioning power-supply or cooling or access-pathways? What’s the point of arguing about instant-on virtualization for data-servers if it takes a minimum of six months to construct the building that houses them? How do we describe disaster-recovery processes for when the IT is out of action, when the only metamodels available to us can only describe IT? To anyone doing real enterprise-scope architecture in the real-world, the myopic inanity of IT-centrism gets really frustrating after a while…

Hence why I’ve been ranting and raging so much about the limitations of TOGAF and the like over the past few years. It’s not because I’m ‘anti-IT’ – as some people have dismissed me – but because I’m trying to get things to work in the real world. A messy, chaotic, uncertain world in which IT is often unreliable at best, irrelevant at worst, and which, for the most part, is not centred on IT. Sigh…

So, in short, the conventional concepts of so-called ‘business-architecture’ are an unusable mess, and the ‘application’ and ‘infrastructure’ so-called ‘layers’ are too narrow in scope to make practical sense for anything other than the most IT-centric of IT-architectures. Hence, also in short, not so much useless as probably worse-than-useless for most real-world purposes.

Which means that we need to start again. Properly.

But from where? Using what as the layers?

(Or do we even need layers at all? Is even the idea of ‘layers’ misleading?)

There’s the Zachman layers, of course: Contextual, Conceptual, Physical, Logical, Implementation, Operations. That does make practical sense as a description of the process of change, but perhaps not so much about the architecture itself – the interrelated, interconnected structure of that which is in use.

What about structural-decomposition – from abstract to detail? Well, yes, that’s useful, certainly, but it doesn’t really tell us much more than Zachman does, and doesn’t help us to differentiate between different kinds of ‘thing’ – the distinctions that come up, if somewhat erratically, in Zachman’s columns of What, How, Where, Who, When and Why.

The ‘Why’, though, does lead to another suggestion: Simon Sinek’s principle of ‘start with Why’, and its layering of Why, How and What.

Because if we start with Why, and tweak the ‘What’ slightly to ‘With What’, we end up with an almost exact match to the Archimate / TOGAF layering – but this time a layering that is not IT-centric. And which also lines up with key parts of the Business Model Canvas:

- Why? – about the choices and Value Propositions that drive ‘the business of the business’

- How? – about IT-applications, ‘manual’-processes and any other Key Activities that enact those choices and needs

- With What? – about any machines, equipment, buildings and other infrastructures and Key Resources upon which or through which those activities take place

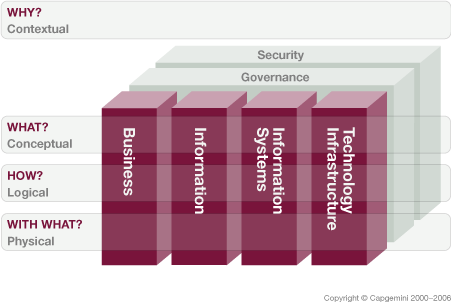

At first glance this has some parallels to the long-established CapGemini ‘Integrated Architecture Framework‘ [IAF]:

(I have a vague recollection that there’s at least one more EA framework that uses a similar Why / How / With-What structure, but right now I can’t remember whose it is… 🙁 – my apologies to that person, anyway.)

But if we look more closely at those layers in IAF, it’s clear that they’re just a re-labelling of Zachman layers, with the old TOGAF-style layers sideways-on, and deeper ‘cross-cutting themes’ such as security and governance further behind. (And actually that’s quite a good way to put it – which we’ll come back to in a moment.)

The point here is that if we use that Sinek-style categorisation of Why, How and With-What, we can cover just about anything that’s needed in the architecture: it doesn’t assume that the end-point is only about IT. And it still lines up well to Archimate: hence business-information (linked to Why) is represented in Archimate as a Business Object, its usage in processes (linked to How) is a Data Object, and its physical form (as a With What) is a Representation. Archimate doesn’t as yet have any entity to represent generic ‘physical Thing’ or ‘thing that flows through processes’ – such as we’d need to represent a parcel in a logistics context, for example – but the Why / How / With-What structure makes it easy to understand that Representation, Data Object and Business Object are just IT-oriented specialisations (in the UML sense) of each of the respective generic entities. It works. 🙂

But should we use layers at all – especially scope-defining layers such as ‘business’, ‘application’ and ‘infrastructure’? In a sense, the IAF suggests not – any fixed notion of ‘layers’ is misleading. A better way to describe is to say that the ‘layers’ are merely areas of emphasis of attention: we separate those areas in order to ‘black-box’ the internals of an area of scope so as to focus our attention on the interfaces between those areas of attention. The IAF shows a very good way to visualise this, with sets of viewpoints that are in effect orthogonal to each other. The only problem there with the IAF is that, yet again, it constrains the overall scope to IT alone – which renders it too limited for whole-enterprise architecture. If we imagine that, rather than that catch-all column labelled ‘Business’, we could have as many columns as we need – and as many ‘backplanes’ that we might need, equivalent to the existing ‘Security’ and ‘Governance’ but covering all values in context for the enterprise – then something like IAF would make good sense.

I would suggest, though, that that simple categorisation would be a good place to start:

- Why – ‘business’

- How – ‘applications’

- With What – ‘infrastructure’

Use each of these not-quite-layers as a viewpoint for focus into the overall enterprise context, and use an adapted version of Archimate or an equivalent to model both within those ‘areas of interest’ and to explore the connections between them.

Okay, that’s it for now: over to you, if you would?

Tom, I think that they relate in a recursive manner (see http://improving-bpm-systems.blogspot.com/2011/02/explaining-ea-business-architecture_19.html ) and the actual recursion is individual in each organisation.

Thanks,

AS

@AS Hi Alexander – strongly agree re recursion, it was something I should have mentioned in the post thanks for reminding me about it. (And I think that ‘other framework’ that I ‘vaguely recollected’ above may have been yours – if so, I hope you accept my apologies for the incomplete reference?)

[I’ve taken the liberty of editing your comment above to correct a minor error with the ‘)’ in the link.]

Lapping these up, I assume like a cat with a fresh bowl of cream. I’m more licking my lips (and paws) for expanding the Social Model Canvas through your thinking through the Not-for-profit aspects. Don’t go back into IT core too much for a business orientated person man like me, struggling to relate to the Social dynamics to find the ways to ‘combine’ these (Business and Social) for contributing to the challenges both parties (and everyone else) has to address.

(A quick note to myself and others, for clarification above)

I got it slightly wrong above re the structure re data and/or physical items in Archimate. The correct layering is as follows:

– ‘Why’ = Business Object or Representation

– ‘How’ = Data Object (no equivalent in Archimate for anything other than data)

– ‘With-What’ = Artifact (could be used for physical instantiation of data, or for physical object)

@Tom Graves (@tetradian)

No problem and thanks for the correction.

Thanks,

AS

I’ve spent a large chunk of a year “starting again” – not with any particular structure in mind, but rather hopeful that something would emerge. I stopped using EA tools and switched to an Ontology editor (TopBraidComposer or Protege, say). I’ve various models that represent collections of business processes (creating a new operating model), information concepts (which relate to these business processes), and “logical” maps that show information flows between application systems (only this model has IT components).

What’s been interesting is the degree of structural similarity, but also some significant differences. In the process and the application models, there is the notion of “flow”, and what flows is some representation of certain classes of information. It’s tempting to say these are different layers, but like you, I’m not sure that they are. It’s more like a different perspective or emphasis.

The process model has recently acquired attributes that do not seem to have an equivalent in the IT model; processes are nested into process-frameworks and each framework (probably recursively) has Outcomes. These differ from the Inputs and Outputs (aka flows), in that they tend to be expressed as “steady state” measures – “full order book”, “positive market reputation”, etc.

As this is an aimless rant, I think my suggestion here is to build whatever models you think you need, and then see how they fit together. But this has to (should be) done in the strong belief that they *can* be joined, and this can only be certain with some deeper (higher?) metamodel.

I’ll ponder some more next week (redundancy looms, so plenty of time).

I had a requirements framework for a book that’s about a decade old. Gosh, I hope you weren’t thinking of that one which uses the who,what… You know I’ve grown my thinking to be in sync with what you write about.

I don’t understand the “obsession” of most Enterprise Architects with layers.

I think of the enterprise as a fractal or small world network of business models.

Seeing enterprises as a small world network of business models fits the organic development of enterprises more then the current rigid guidelines, reference models & concepts of TOGAF/ArchiMate.

For me the business model canvas tool is a great way to describe and connect all those individual business model nodes in a similar way and connect them through standard connection points (key partners & customer segments, costs & revenues).

Advantages of looking at the enterprise as a small world network of business models:

– you can start modeling from any point or perspective (or multiple points) you want, bottom-up, top-down, sideways or whatever other direction you like

– models become flexible, scalable and maintainable

– no need for difficult specialized EA tools & languages

– the model is built with a simple set of concepts everybody in a business environment can understand and talk about so that modeling will be a social activity where everybody can participate and give feedback

But most of these advantages will probably seen as disadvantages by most “old-fashioned” Enterprise Architects…

Tom

As the ‘Strategy’ chapter of Business Model Generation illustrates, there’s a whole lot of market architecture that needs to be known and modelled before deciding on a business model and then filling-in the Canvas. That’s similar to a buildings architect knowing a lot about the surroundings in which a new building will be sited, before starting to sketch, design and model the building.

To pick up on Peter Bakker’s observation, the ‘market architecture’ in Business Model Generation isn’t in depicted in layers, either, nor is it explicitly included in the Canvas. With the business-model-centric view that the book is founded upon, it’s depicted as four-dimensional incoming forces (“Macro Economics”, “Foresight”, “Competetive Analysis”, and “Market Analysis”). With enterprise- and experiences-centric views, the strategy is founded, instead, on understanding how the business in question contributes to the enterprises and experiences of its multiple stakeholders (customers, agents, investors, employees, regulators, partners, suppliers, etc), all of whom are of course experiencing other businesses too.

So the answer to the question you’re asking starts, I believe, with appreciating that the architecture of a business is largely a multi-faceted extension of the architecture(s) of the market(s) in which it appears, rather than a separate entity with its own self-contained architecture. Once that’s established we can find what is truly unique about the enterprise, and business, that we’re designing, and make sure that this uniqueness is placed at the very heart of both our designs and their on-the-ground implementations.

One of the earliest practical applications of this, I remember, was in my days as an Information Architect (1994-6). Our principle was that we always model the ‘outside world’ data structures first, as if our enterprise didn’t exist. Only when were satisfied with that model would we move ‘inside’ to discover what was unique about our own data structures (not much, was always the answer). Later, we applied the same principle to modelling processes, to great effect.

Hope that helps.

Chris

Hi Tom,

I’ve been thinking along similar lines. My ideas are very nebulous at this point in time, not at all fully formed (the labels I’m using here are completely arbitrary), but ran something along the lines of a “Why” layer, a “Business Capability” layer, and an “Execution” layer where people, process and technology would come into play. I think that conceptualising architectures like this aids in traceability and in designing solution architectures because solutions are not just composed of IT elements, but focussing on IT means that non-IT aspects are ignored to thedetriment of the overall success of a solution. I think you have hit on a central weakness of TOGAF and similar frameworks – though I can’t say that I think that Zachman is an improvement here.

Doug

Speaking from my background in cognitive philosophy I would say metaphors make good servants but terrible masters. (Another term is idealised cognitive models). Take the concept of layers. In the end it’s a metaphor. Layer is a physical spatial concept. It’s a useful concept for thinking about other things that have layer-like qualities, but in the end the metaphor breaks down and we start struggling with its deficiencies. Business capabilities, the processes that enact them, the information that is created and used in that activity, the software that manipulates the information, the hardware on which it runs and the buildings that house it and the cables that power and connect it all, do not actually exist in any kind of layer, conceptual or otherwise. There is no neat, consistent ontological hierarchy in which these things are ‘layered’.

That we can order our basic concepts into regular polyhedrons on a sheet of paper and create x-y-z axis arrangements that suggest causal dependencies does not mean we are representing reality or identifying causal relationships accurately.

EA frameworks are usually like maps of imaginary countries. Real maps are extremely powerful tools because there is an objective correlation between the abstraction and the thing being abstracted (the terrain) that can be measured and which applies in exactly the same way to all other concepts that can be represented on the map – topography, rainfall patterns, building types, population density, frequency of violent crime, bus routes, locations of McDonalds, Schools, and Churches. All these things can be objective related and analysed by virtue of location on a common system of measurable coordinates.

EA frameworks are not, of course, complete fantasies. But unlike a street directory which is an actual representation of something that has been observed and measured. Most frameworks are diagrams of intuitions of causal relationships relying too heavily on inconsistent spatial metaphors.

I need to read Ric’s comment again when I’m more awake but I think I (strongly) agree with him – even though my next sentence is going to sound like I don’t. There are, in my opinion, meaningful layered models, of which the most obvious is the OSI 7 layer model. I regard this as meaningful, because the functionality delivered by each layer is cohesive and decoupled from that of the layers above and below – and all communication/collaboration is strictly and only between adjacent layers. So, even though it’s only a metaphor, it’s a useful metaphor.

The problem is that the layering metaphor is horrendously overused. It’s as if the use of the metaphor made something necessarily true – whereas most layered models I see are in no sense meaningfully layered. I mean the reality doesn’t work like that. The result is a misleading picture, which avoids rather than resolves real complexity. That’s pretty much what Ric says in his second paragraph. Marketing people like them too, for the same reason – making something look prettier than it is.

The irony is that whilst IT architects are the worst offenders, the few situations in which we can meaningfully speak of layers are technology designs (not necessarily IT).

So if we use the metaphor, we need to be very sure it does not become our master but is actually helping us to convey an idea in a meaningful way. One could say “only use it if…” But exactly because it’s so over used and misused, I would put in a plea for “avoid it unless…”

Why not just test any framework on a business or a process that doesn’t need IT to run? In your comment #4 I think you’re on the right path. If, for example’s sake, we take a more atomic approach and go down on a process level then we could go with:

– objective: I need to hang a picture on the wall.

– why?: to satisfy a certain family member.

– how?: make a hole in the wall, put a nail in and hang it there

– with what?: a nail and a hammer.

– why did I choose that solution? The picture frame was heavy so there had to be a more permanent solution as opposed to gluing it. And it’s a wooden wall so no drilling is necessary.

With this in mind I would have to add a feedback, ie. why did we choose to do this with that? (or why did we choose this kind of infrastructure and not some other kind?) This way the first why is connected to the strategy via business goals and the second why explains why this was the best option at the time to fulfill the business goal.

There it is. No IT. I suppose this could then be used generally to describe business architectures (few I guess) that don’t use IT or use it in a very limited way (for example: a building company, a hairdresser company, a bakery, etc.)

I do quite often compare business architecture to a classic – building architecture – draw a house or a bridge – you have frameworks on how to do it, what to include, what to test it for, constraints, etc.. If current enterprise architecture frameworks only see IT solutions then this is surely a drawback. IT should fall into an infrastructure layer (with what) so it is presented as any other part of infrastructure needed to run a business (a dredging machine, a warehouse, trucks, people, phones, etc.)

Stuart, thanks. I agree completely: the OSI stack is quite amenable to being described as a set of layers. In fact the whole suite of technologies is deliberately built that way. I like that you picked it because it is informative as an alternative illustration of my other point – abstractions that seek to order real relationships – especially causal ones – require a common reference – a unit of measure or objective concept through which all other relationships and quantities may be expressed. I chose the map example because of its familiarity. Maps are useful for all manner of analysis and planning because they do a brilliant magical thing, they express the relationship and interaction of widely diverse kinds of things in terms of a simple, easy to understand, verifiable characteristic: Location. Introduce time as another variable all these things can share and the possibilities are infinite. The OSI stack is likewise reducible. Everything in it is eventually about moving electrical signals around a network. One can objectively trace the operation of a HTTP Put operations to electrical switches – (If you really wanted).

Maps aren’t actually metaphor, nor are the OSI layers. They are isomorphic abstractions of real things. Drawing a rectangle and labelling it infrastructure services, then popping some more rectangles on top labelled application services, and putting another overlapping one to the side labelled security services, and so on, is most definitely a ‘metaphor’. Such diagrams are manifestly not models of IT architectures, they are models of how we think about the importance of the various functions of IT infrastructures. From a real management, design and planning point of view, it should come as no surprise they are next to useless for anything other than being slightly easier to read that a bullet list.

Many, many things within any large organisation are layered – by virtue of direct composition, or some other dependency. But no organisation can be abstracted to a set of layered domains.

In summing up lets look to another familiar but complex object – the human body. It is comprised of interrelated composable parts, systems and subsytems, processes and functions. Certainly one can accurately represent aspects of anatomy or metabolism through simplified block diagrams, flow charts, etc. But it would be absurd to abstract the operation and structure of the body the way EA frameworks abstract the operation and structure of organisations and consider the result a tool for deciding the next stage of our evolution. And something of a conceit.

I think we need good frameworks, effective vocabularies and concepts that can reliably represent the actual causes and effects of the behaviours of the complex social systems we call ‘enterprises’. But we desperately need more commitment to empiricism and science and a judicious application of Occam’s razor to TOGAF, Zachman, FEAF, et. al.

Tom,

forgive me for ranting a little on your blog. I have been also going over the Business Model Canvas. Mainly because I thought perhaps the approach it takes offers a clue into finding the Rosetta Stone of architectural domains. Or in terms of my cartography example the latitude and longitude of EA. How does one express the architecture of a software system in terms of an enterprise ontology, or an information asset in terms of data centre consumables, and a business outcome in terms of a communications platform. The canvas presents a compelling complete picture of a business model There are only four tangible categories: partners, customers, resources, and activities. The others should, in the end, be effects of how these for are configured. (I recognise that cost structures would be arguable but I have reasons for not considering that one a ‘tangible’).

The main problem with the canvas as I see it is combinatorial complexity. Even if you reduce the task to expressing each of the four I have selected in terms of the other three, once you start filling in the details of an actual organisation the level of complexity will rapidly get beyond any rational cost-effectiveness.

And even if this were possible, I am not sure it could overcome the fact that a large (and obviously unmeasurable) part of any organisation is informal. But often the informal aspects of an organisation make a significant contribution to its effectiveness.

The idea that there are “layers” of abstraction here is a popular one. Thus a database record representing a truck is somehow more “real” and more “physical” whereas a description of the truck in a requirements document is somehow more “abstract” and more “conceptual”. I can see that that idea makes a lot of sense for those who adopt an IT-centric Weltanschauuing, in which the ultimate reality is a magnetic bit-pattern in some data store.

Meanwhile, business people may suffer from the strange illusion that it’s the truck that is the ultimate reality, and it’s the database record that’s only an abstraction.

Only an abstraction, huh?

I think it’s much more useful to think about viewpoints (separation of concerns) than about abstraction layers. One of the key messages of RM-ODP was that the viewpoints were not to be regarded as layers. Different stakeholders are interested in different aspects of reality, and I don’t think it’s useful to regard (as Zachman and TOGAF both implicitly do) the IT aspects of reality as being more important than any other.

@Peter Ward Great comments, Peter – thanks!

On using Protege for EA, have you seen The Essential Project? That’s a free/open-source EA toolset that’s built on top of Protege. (Their metamodel follows the usual ‘Business’ / ‘Data’ / ‘Application’ / ‘Technology’ (i.e. IT-specific infrastructure) layering, so will still be limited to IT-architectures, but could well be useful as a base from which to experiment.)

Will look forward to further comments/advice from you, anyway.

@Peter Bakker – Peter, I do take your point, and I don’t disagree.

The other side, as I think several other people have commented by now, is that notion of ‘layers’ provides a useful metaphor. And there are some concrete aspects to the ‘layers’-metaphor: the OSI-7 ‘stack’ that Stuart mentions, for example; or distinct layers of abstraction, each layer adding another category of attributes to the description. A ‘layers’-metaphor can also be a useful way of describing perceived relationships and interrelationships between viewpoints. And those viewpoints in turn can describe the significantly different ‘worlds’ of of different actors in the transitions between strategy, tactics, design, implementation and operation.

It’s only a metaphor. The problems arise when people take the metaphor too seriously, in either direction, and forget that it’s only a metaphor…

@Chris Potts – Chris, again, I do agree.

For example, you say, “So the answer to the question you’re asking starts, I believe, with appreciating that the architecture of a business is largely a multi-faceted extension of the architecture(s) of the market(s) in which it appears, rather than a separate entity with its own self-contained architecture.” That’s exactly the approach I recommend for enterprise-architectures, though from our discussions it may be possible that I start one layer further out than you do.

My problem, though, is that in far too many cases the people I’ve worked with don’t start off working that way, in fact it’s been a real struggle to get them to work in an ‘outside-in’ way. Instead, they start from an organisation-centric view, of “customers appearing in our processes”, as I think you would put it. And, as you again put it, that kind of view doesn’t work well at all – but they can’t see it, because everything is interpreted in terms of the mythical ‘layers’ of that organisation-centric structure.

It gets even worse when dealing with many IT-folks, because many seem constitutionally incapable of comprehending a world which is not solely centred around IT. The standard TOGAF-style ‘business-architecture’ is an ‘inside-out’ view of the business-context as seen from within another inside-out view – compounding the ‘layers’ problem even further. I must admit I do despair of it sometimes… 😐

@Doug Newdick – Doug, thanks also, and glad to see that we’re thinking along similar lines.

On “I can’t say that I think that Zachman is an improvement here”, I do find the Zachman layers-of-abstraction useful, not least because each ‘layer’ tends to engage a different set of stakeholders. But the Zachman columns are a misleading mess, as I’ve written about in some detail several times here and elsewhere – I’d agree with you on that.

@Ric Phillips – Ric, “metaphors make good servants but terrible masters” – beautifully put! Very strong agree, as in my reply to Peter Bakker a few comments above.

Re “There is no neat, consistent ontological hierarchy in which these things are ‘layered’”, again, very strong agree. As someone else puts it in another comment, these are not so much ‘layers’ as convenient perceived-relationships between fairly-arbitrarily-selected viewpoints. People choose to describe these ‘layers’ as having some kind of concrete existence, and then somehow forget that they’re just an arbitrary choice. Your point about ‘servant vs master’ again, yes?

@Stuart Boardman – Stuart: “The problem is that the layering metaphor is horrendously overused.” Yup: don’t think I need to say any more than that, do I? 🙂

@Aljaz Prusnik – Aljaz: yes, nice challenge for any framework.

On “I would have to add a feedback, ie. why did we choose to do this with that?”, agree strongly. The whole point is that it’s not simply a top-down exercise, it’s iterative, going both ways (or every way, to be more precise). One of the problems with the ‘layers’ metaphor is that it tends to reinforce a Taylorist top-down-only myth: that’s actually a more important habit to break than the habit of seeing things in terms of layers.

On “I suppose this could then be used generally to describe business architectures (few I guess) that don’t use IT or use it in a very limited way”, every business has to be able to run without IT when the IT’s no longer there! 🙂 One of the thought-experiments I often do with clients is to get them to explore how long their business will last without IT: in many cases they’d be in deep trouble within hours at most, and possibly out of business in within days. I then walk them through some of the disaster-scenarios that could put their IT either mostly or entirely out of action for considerably longer than those time-scales. It’s at that point, once the shock has worn off and the blood slowly returns to their faces, that they start to take a non-IT-centric view a bit more seriously… 😐

This is why I keep on saying that there is no single ‘the centre’ to an enterprise-architecture: any point at all could be a point of failure, or a start-point for recovery, hence everywhere and nowhere is ‘the centre’, all at the same time.

@Ric Phillips – Ric: some form of set-theory is probably useful here, exploring scopes of viewpoints into a kind of ‘holographic’ space, perceived relationships between those viewpoints. ‘Layers’ are just one special-case of set-scopes/set-relationships; likewise ‘columns’ etc. My own opinion is that I’m extremely wary of anything that provides clear-cut absolute separations between sets: most real-world sets have overlaps of some kind, if only to allow interchange between them. (The age-old architecture trick: recognise that the ‘boxes’ are important, but it’s just as important to pay attention to the ‘lines’ that connect between them.)

On “we desperately need more commitment to empiricism and science and a judicious application of Occam’s razor to TOGAF, Zachman, FEAF, et. al.” – again, strong agree, because that’s largely what I’m aiming to do here. Particularly the Occam’s Razor bit, anyway: I’m somewhat wary of much of what purports to be ‘science’ in this space (the Enterprise Ontology group, for example), because much of it seems to be leading straight back into the Taylorist trap where complexity is misportrayed merely as a more complicated form of complication. Not everything is amenable to conventional combinatorial science, after all… 🙂 – in fact that’s how wicked-problems get created. We need to be careful there too…

@Ric Phillips – Ric – no complaints about ‘rant’, I do enough of it myself! 🙂 Besides, everything you’re saying in this ‘rant’ does make sense, so no complaints on that score either.

I do like your simplification of the Canvas to just those four categories – though I’d suggest that you could reduce it one stage further, since Customers are also Partners in the business-model too. I’m not sure that you could so easily ignore Value Proposition, though: done properly, it’s actually the real core of the business-model.

Very strong agree about the importance of the the ‘informal’ in a business-model, especially in relation to overall effectiveness. Too many people seem to expend too much Taylorist effort to eradicate the one thing that really makes the business-model work… 😐

@Richard Veryard – Richard – thanks, and strong agree about the example of actual truck versus record-of-the-truck. I’ve had very similar arguments with IT-people in a logistics context: they really could not grasp the idea that the fact they had a record of a parcel did not in itself assure that the parcel was where the record said it was, or even whether the parcel ever existed. I really do despair of some people’s (non)-grasp of reality sometimes… sigh…

Strong agree, of course, re “I don’t think it’s useful to regard (as Zachman and TOGAF both implicitly do) the IT aspects of reality as being more important than any other”. Also sigh… 😐