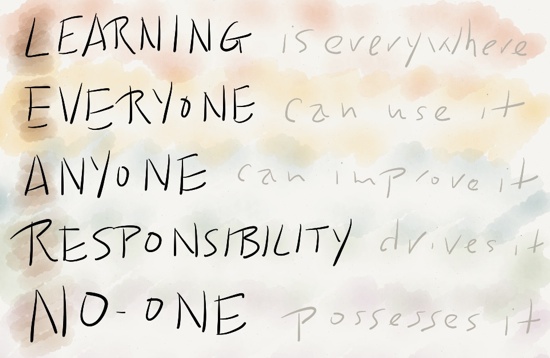

The LEARN principle

The LEARN principle extends the NEA principle of the internet to the context of global knowledge:

- Learning is everywhere.

- Everyone can use it.

- Anyone can improve it.

- Responsibility drives it.

- No-one possesses it.

The NEA acronym stands for the maxim “No-one owns it; Everyone can use it; Anyone can improve it”. The maxim was first presented by Doc Searls and David Weinberger in their 2003 essay ‘World of Ends. What the Internet Is and How to Stop Mistaking It for Something Else‘. To quote Wikipedia, the purpose of NEA was to explain the nature of the Internet itself:

that it cannot be owned by any individual corporation because it is an agreement not a thing, that potentially everyone on earth can have access to it, and that anyone can potentially start a new service or even improve the nature of the agreement with a new good idea.

In essence, the NEA maxim applies to one specific aspect of learning and knowledge: one of the means of access and sharing. The LEARN acronym extends this more generally as follows:

— Learning, and opportunity for learning, is everywhere, and is shareable everywhere. Learning is embodied and enacted knowledge; and in turn, knowledge is personally-understood information. The internet provides a valuable source of information, and often of methods understand, embody and enact that information; yet it is merely one amongst an infinity of other potential sources for information and methods for learning. Although learning itself is always personal, there are many types of learning-opportunity that arise primarily or solely within a social context – hence the ‘shareable’ nature of learning.

— Everyone can use that learning and knowledge. Whether they may or will use that knowledge is another question – but everyone can use it, if they so desire, and develop the personal capability to do so.

— Anyone can improve that learning and knowledge. Because learning is personal, each person provides their own unique insight into the respective learning-context. And because learning is also shareable, each insight may become shareable too – extending the available scope of knowledge.

— Responsibility is what drives that learning and use of knowledge. The core drivers for the quest for new knowledge and new learning sit somewhere between curiosity and need. In practice this comes out as new responsibility – literally, a personal ‘response-ability’, an expanded ability to choose and enact one’s responses to each different context. This also implies responsibility as stewardship for the learning and knowledge – ensuring that it is shared, applied and enacted appropriately.

— No-one can possess that learning or knowledge – particularly so in the sense of a purported ‘right’ to exclusive-possession of that knowledge. Learning always exists in a social context, hence it is inherently both personal and shareable. More to the point, since personal-knowledge is personal, the personal aspects of learning, knowledge and skill will literally die with that person – hence if they are not shared, the learnings will eventually cease to exist.

The last two points contrast two fundamentally different concepts of ownership: responsibility versus possession. For example, a direct corollary of the LEARN principle is that the concept of ‘intellectual-property’ as exclusive-possession is inherently self-defeating: by its nature, any attempt at exclusive-possession of information or knowledge must inevitably lead either to the loss of that knowledge over time, and/or to eventual ‘leakage’ and loss of control of exclusive-possession – possibly without awareness of the need for responsible use of that knowledge.

The so-called ‘information-economy’, which attempts to treat all ‘proprietary’ information in the exact same way as for scarce physical resources, is again inherently self-defeating. Amongst other implications of that fact, there is an urgent need for a fundamental rethink of the role of information and knowledge in the global economy, in line with the nature of the LEARN principle.

The underlining question for most will be the association of “money” to the “ownership”. The reason an “idea” is trademarked and “owned” as IP is for the increase and protection of “money”. So…to rethink the role of information and knowledge need to start with the disassociation of “money”?

Pat – “So…to rethink the role of information and knowledge need to start with the disassociation of “money”?”

As I’ve described in other posts some while back, what’s actually needed is a disconnect from the notion of ‘possession’ – the subsequent disconnect from the notion’ of ‘money’ is just one minor side-effect of that.

Associating knowledge and learning solely with money is a really quick way to detach from the reality of value, and thence to lose most or all of the actual value. It’s kinda scary just how far down the rabbit-hole this one actually goes… but the first stage is to start to understand the value of learning and knowledge in its own terms, and for its own sake.

Sure, we don’t have much of a chance to deal with the insanities of the ‘money-economy’ as yet; but we can and must get this right at least within our organisations. For example, one of the most common causes of dysfunctionality and ineffectiveness within organisations is the tendency to information-hoarding, either by individuals and/or within silos, in the mistaken belief that withheld-information inherently provides ‘power’ to those who withhold. It doesn’t: all it does is cause the loss of information, or at least of timeliness of information, in the places where the organisation actually needs it. In other words, this isn’t ‘Tom-idealism’: these are real, urgent, and, yes, money-important issues that are fundamental to the operations of an organisation and its architectures.

“we don’t have much of a chance to deal with the insanities of the ‘money-economy’ as yet;”

Can businesses see the value of learning and knowledge without seeing a financial reward?

I see the “need for possession” of information and the lack of transparency is because the need for money in the current state of affairs. It’s a means to an end in many businesses.

” It doesn’t: all it does is cause the loss of information, or at least of timeliness of information, in the places where the organisation actually needs it.”

Agreed but those at the top of the chain in businesses do not.

Hi Pat – rebuke accepted. 🙂

I think I need to backstep a little here, in particular around my earlier comment: “It’s kinda scary just how far down the rabbit-hole this one actually goes… but the first stage is to start to understand the value of learning and knowledge in its own terms, and for its own sake.”

There are several distinct things going on here, and it’s important not to confuse them or mix them up:

— the ‘rabbit-hole’ of the non-sustainability of the possession-economy

(that’s a literally fundamental issue, but I’ll skip over it for now, because it still seems way too scary to face for just about everyone at present – especially “at the top of the chain in businesses”)

— the nature of value-flow in the enterprise

(I’ll do a separate post on this, because it needs a more explicit explanation)

— the actual location and ‘physics’ of knowledge and learning

(for which I’ll do a quick summary here)

The key points here:

— learning is personal

— especially in the longer term, information survives only by being used and shared

It’s true that data can be stored independently of real individuals, and some information too. But learning and knowledge – the appropriate application of that data and information – can only exist as embodied in real-people.

So think of this in a personal sense – your own knowledge and learning. It’s literally embodied in you: hence the only way someone else can ‘possess’ it is if they possess you. Which they can’t – not in law, anyway – and even if they did, the reality is that you would be unlikely to be willing to share it with them, because they treated you as their ‘possession’. In the context of learning, the act of ‘possessing’ in effect destroys that which is ‘possessed’.

If you don’t use your knowledge and learning in some way, it may as well not exist.

And if you don’t share it, it will literally die with you.

These are fundamentals: part of the ‘physics’ of learning and knowledge. Abstract notions such as financial profit from learning and knowledge will only work if they work with that ‘physics’ – not against it. And notions of ‘possession’ work directly against that ‘physics’.

There’s no political point I’m trying to make here, or an ‘anti-capitalist’ point, or whatever: this is solely about architecture and design for the enterprise. All I’m saying here is that – exactly as per building-architecture – anything that ignores the physics of its materials is inevitably heading for a collapse: and any kind of collapse – especially on a large scale – tends to be messy, painful, and very unpleasant for all involved. If we want to avoid a messy, painful and very unpleasant collapse around learning and knowledge, we need to design in accordance with the LEARN principles. Simple as that, really.