Money, price and value in EA (shorter version)

The previous post on ‘Money, price and value in enterprise-architecture‘ was kinda long, so here’s a (somewhat) shorter summary:

Background

It’s fundamentally important that enterprise-architectures should incorporate the following assertions:

- there are many other forms of value besides money

- in most aspects of enterprise-architecture, money is not the form of value that matters

- in many ways, this applies more to commercial organisations than to non-commercial ones

These assertions clash with many common assumptions about the nature of business, and the architectures that are needed to support that business.

However, failure to fully incorporate those assertions creates a real risk of developing architectures that will guarantee the failure of their respective businesses.

The core problem, and risk, is that if we over-focus on money, we destroy the real value – and thence usually the money as well.

This article explores the architectural implications of those assertions, using the core theme of Enterprise Canvas that “everything is or represents a service”.

Organisation and enterprise

‘Enterprise-architecture’ here is the architecture of the enterprise as a whole, not solely the enterprise-IT.

We develop an architecture for an organisation, about its enterprise:

- the enterprise is a social structure, primarily emotive/aspirational in nature, defined by vision, values and mutual commitments (the enterprise is – it provides motivation, ‘why?‘)

- the organisation is a legal structure, primarily conceptual/physical in nature, defined by rules, roles and responsibilities (the organisation does – it provides action, ‘how?‘)

In essence, the enterprise is just an emotive idea – for example, the TED vision of ‘ideas worth spreading’. An organisation exists to implement some aspect of that idea.

For this context, the enterprise-in-scope is some three steps larger than the scope of the organisation itself: first, the organisation’s supply-chain or direct value-network; then its overall market; and outward again to the broader social context in which that market exists.

A commercial organisation needs to ‘make money’ in order to operate, and continue to operate, within its market. Yet the market and, in turn, the organisation, will operate in the context of the overall enterprise – and the enterprise determines what ‘value’ is within that context.

To understand where the money comes from, and goes, we must always start with value.

Value and values

In Enterprise Canvas, everything is described in terms of services. (Products are ‘proto-services’ that enable self-delivery of service.)

Each service serves: it contributes in some way towards the aim or vision or ‘desired ends’ of the respective enterprise, and is a means via which some aspect of the ends of the enterprise may be achieved.

Every service within the organisation would or should also contribute towards those desired-ends. The organisation itself is a means to achieve the enterprise’s aims.

The enterprise-vision determines what value is within the context. This is expressed as values and, in more actionable form, as rules and principles.

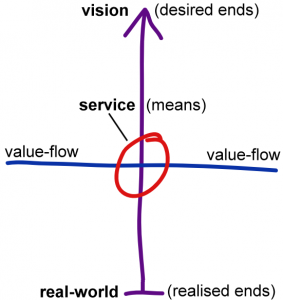

Services serve and enact the values of the overall vision, and, usually, exchange various forms of value with other services. In Enterprise Canvas, we depict this as a vertical connection with enterprise-values, and a horizontal flow of value around the services of the enterprise.

Each service makes an offer – a value-proposition – that establishes what the service can provide that would be perceived as ‘of value’, in relation to the values of the enterprise.

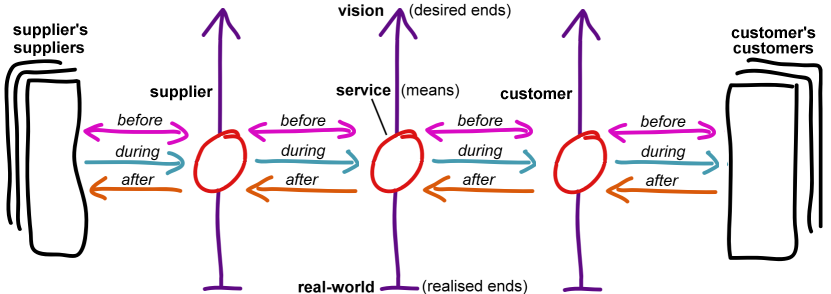

An enterprise consists of services, each with their own value-propositions, exchanging value in roles as ‘service-providers’ and ‘service-consumers’. Hence, for example, a ‘supply-chain’:

The market provides a context for transactions take place, and provides rules and governance for those transactions.

All of this takes place within the broader context of the shared-enterprise – which determines what ‘value’ is, within that enterprise and market.

Price and value

Most conventional business-models focus only on transactions, and on monetary costs and returns from those transactions.

Price is a translation – a valuation – of the perceived-value of something, usually in terms of a ‘fiat-currency‘ that provides a standardised means to exchange ‘rights’ to valued resources.

Pricing is always a complex, non-linear transform, and most of those transforms are non-reversible – hence we usually can’t use money itself to determine the totality of perceived-value. Pricing is also only one specific approach, amongst many, to understand and model value. Monetary models also apply severe constraints on what types of value can be described.

The transactional focus for most pricing, and most ‘valuation’, encompasses only a small part of the ‘market cycle’:

If we focus only on transactions, the market-cycle will eventually break, and with it the real connection to value – which in turn breaks the connection to value-flow, and thence to money. In short, losing the link to value equals losing any link to money.

We can split this architecturally in terms of what needs to happen before, during and after the nominal transactions between services:

— Before any transaction happens, there are interactions that revolve around trust, or reputation as a kind of proxy for trust. The organisation will need to acknowledge and find ways to resolve those uncertainties, not least because they have a deep impact on perceived-value.

There are interactions around relationship-building. Without some sense of relationship, there’d be little perceived reason to connect with the organisation itself. No relationship means no connection to value means no reason-to-transact means no transaction means no possibility of profit.

There are also interactions around conversation, in which the conditions and trade-offs of a potential transaction are worked out – including assessment of perceived-value, and thence the comparison between perceived-value and price or cost.

— During the transaction, the service delivers on its service-offer, the value-proposition. Note that unless the the service-offer is about money itself, money isn’t much involved at this point: it’s still in the realm of ‘price’.

— Only after the transaction – and then usually only in a commercial context – will money come directly into the picture. Note again, though, that money is only one form of value, one form of cost: there are likely to be (many) others, as per the enterprise vision and values.

Money comes properly into the enterprise picture after all of the business-critical activities – the actionable, changeable, designable activities – have already happened. In our architectures, if we focus only on money, we block the view to all of the things that make that money happen.

Price is one specific view of the relationship between perceived-value and money; and this economics, money is the interchangeable token for access to items-of-value. Yet in most cases, money is not value itself: it’s only a proxy for value. Failure to grasp that distinction leads to all manner of problems, in enterprise-architectures and elsewhere.

‘Making money’ may be seen as the reason for doing business: yet it’s usually not what the enterprise is about – and the organisation does its business only in the context of that enterprise. For example, if the focus of the enterprise is ‘ideas worth spreading’, and the organisation is focussed only on ‘making money’, it’d literally not be in the same enterprise – and hence not likely to make much money.

For a commercial organisation, the way to make money is to keep the focus on the shared-values of the enterprise – not on the money. Paradoxically, the way to make money is to focus on everything other than the money: we need to keep attention on the whole of the market-cycle, rather than solely on the ‘money-making’ transactions in that cycle.

For architectures, don’t allow price or money to distract us from value – because value, not money, is what underpins the enterprise.

Money, investment and ‘owners’

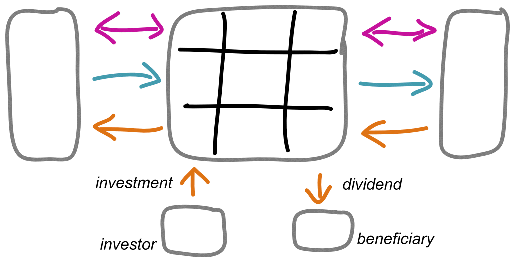

In a sense, investors are just another kind of service-provider; likewise beneficiaries and service-consumers. Yet in Enterprise Canvas, we model them in separate roles:

One reason is that value-flows from investors and to beneficiaries tend to go the opposite direction to those of their provider or consumer counterparts: the types of values provided or delivered – such as money – are those that tend to arise only in the backchannel, the ‘after’-transaction flows, rather than those in the main transactions.

The first complication is that there are many types of investors, who invest many types of value. For example, parents may support the young members of a startup: money is often part of the value-picture there, though rarely the only one. A community supports the social fabric within which enterprises and organisations can do business. A true whole-of-enterprise view provides a much richer, more complex and more accurate picture than the simplistic money-only view.

The next complication is that investors may expect returns from their investment in forms of value that may not be the same as those that they’d invested. For example, parents invest money in the startup, but hope for returns in familial satisfaction; a community invests space and social-sanction, but expect returns in the form of stability, certainty and social-support. Even where the investment has primarily a monetary focus, the return may not be directly monetary as such. Getting the balance right between all of these interchanges is neither simple nor straightforward.

Those complications can be made a lot more difficult if we make the mistake of thinking that money is the only valid form of value. For example, the community and others may invest vast amounts of non-monetary value into an organisation’s business, but the organisation focusses on converting as much value as possible to monetary form, as returns solely to the financial-investors. The result is that whilst the organisation may seem highly profitable for the financial investors, at some point it will suddenly lose its societal ‘licence to operate‘. Architecturally, this is a known anti-pattern that all but guarantees business-failure.

The most serious complication is that we have two fundamentally different types of investor/beneficiaries:

— The first type invest as part of their commitment to the same enterprise. This is essentially the same type of value-flow as in the main transactions – though the value-flows go ‘backwards’, as described above.

— The second type are not committed to the enterprise and its values, but seek returns in forms of value other than those of the enterprise. These investors may be necessary to the organisation, but their own focus is on a different enterprise – for example, ‘making money’, rather than the TED enterprise of ‘ideas worth spreading’. If we allow these investors to distract us into paying too much attention to the demands of their chosen enterprise, we will lose focus on the enterprise that our organisation actually does its business in – a guaranteed recipe for business failure.

All of this is made much harder by the social-myth of financial-investors as ‘owners’ of the organisation, because their views supposedly take priority over everyone else. If their enterprise does not align with the enterprise of the organisation (which it often doesn’t), there’s then a very high risk that their enterprise will take priority over the actual enterprise of the organisation – leading directly to all of the problems described above.

Hence, paradoxically, the best way to make money for financial investors is to ignore the demands of the financial investors, and keep the focus of the organisation on the enterprise-values instead.

—

Comments, anyone?

Leave a Reply