Complex, complicated, and Einstein’s dice

What’s the real source of that infamous ‘business/IT divide’? And is there a way to bridge it? The answers would seem to be both complicated and complex – and might involve Einstein’s dice…

At which point I probably ought to backstep a bit? 🙂

Background here I’d allowed myself to become tangled in one of those long, involved back-and-forth sort-of-discussions that erupt on Twitter from time to time: in this case, primarily with Kai Schlüter and Rory Cleland , about whether (and if so, in what ways) enterprise-architecture could be described as art or science. The short answer is ‘both’, of course – both art and science – though Kai and I argued for more emphasis on the former, and Rory for the latter.

Yet this is actually about perspective, or paradigm – and it’s the same paradigm-clash as that which underpins much of the ‘business/IT divide’. (And, for that matter, CP Snow’s equally-infamous ‘Two Cultures‘.)

And behind all of that – or so it seems to me – is the drive for certainty. Or perhaps even more, the drive against uncertainty. Which is where this gets interesting…

Consider engineering, for example. The whole thrust of that discipline has been about taking something that, in the natural world, is unusual or uncertain – such as a gas-explosion – and identifying and then providing conditions under which it becomes more certain and useful – such as the gas-explosions that drive a car. The better we understand whatever-it-is, the more reliable we can make it, and usually more efficient, too. It’s complicated – sometimes very complicated – but it works: and we all know that.

Yet the very success of this process tends to give the impression that everything is reducible to certainty in this way; and thence that we can control everything in this way, too – because once we know what those conditions are, what buttons to press, what traits to tweak, we can control it. To many people, that’s something that’s very desirable indeed: and they’re definitely willing to go to the effort to make that happen. (Or, perhaps more usually, that someone else should go to that effort on their behalf – which is another story, of course…)

On the other side, there are many disciplines that are a lot less certain about certainty – or perhaps less uncomfortable with uncertainty. To many of these people, certainty is something that is often not desirable: perhaps because it seems to leave no space for the humanness of life, for example, or because, by definition, innovation is possible only where there is at least some degree of uncertainty.

And then we have the pragmatists – the people on the front-line of business, for example, who might well agree that in theory it might be so that everything should be predictable, but in practice, right here, right now, the world they deal with darn well is uncertain, whether they like it or not.

So there’s something of a three-way clash here, between:

- those who desire or demand certainty – CP Snow’s scientists (or, in business, the middle-managers and the investors);

- those who insist on the existence of uncertainty – CP Snow’s artists (or, in business, the innovators and some of the executives); and

- those who don’t much care either way, but just want to get something done amidst all the messiness of the real world.

It’s the latter group where architecture really fits, but we still have to deal with the other two groups – and, for that matter, identify them well enough to work with them. And perhaps the key word to watch for, and work around, is complexity.

To the ‘scientists’, ‘complex’ is synonymous with ‘very complicated’ – or rather, that complexity is a kind of quantitative measure of complicatedness. Ultimately everything should be predictable: things that are supposedly complex are just those items that we haven’t got fully under control as yet, but we will do soon, if we keep working at it. Hence, for example, IT-architects such as Roger Sessions, who argue that the real role of architecture is not merely to reduce complexity, but to eliminate it entirely.

To the ‘artists’, ‘complex’ is qualitatively different from ‘complicated’: no matter how hard we work at it, we’ll never be able to reduce them to simple algorithms of control. In that sense, complexity is a kind of quantitative measure of the inherent uncertainty in a context. Hence, for example, business thinkers such as Nassim Taleb, who argue that we will never be able to eliminate the ‘Black Swans‘ of uncertainty – and would not be wise to attempt to eliminate them, either.

And that’s the ‘IT/business-divide’ in a nutshell:

- IT-folks prefer the ‘scientist’-style view of the world – because machines do need certainty, otherwise they often won’t work at all

- business-folk prefer something closer to the ‘artist’-style view – or at least the pragmatic view, which must somehow accommodate both.

Even in science, though, there’s much the same dichotomy. Einstein was apparently appalled at Bohr and Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle: “I am certain that God does not play dice with the universe“, was his much-quoted retort. But whether Einstein liked it or not, uncertainty still remains one of the few certainties in science, and unprovability one of the few certain proofs. If they apply in the sciences, they’d certainly apply in business too – and hence also in any architecture of the enterprise.

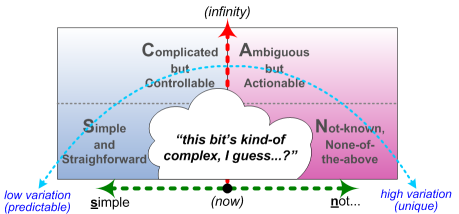

Which brings us, in turn, to that relationship between ‘science’ and ‘art’ in enterprise-architecture and the like – for which it’s easiest here to illustrate with the SCAN frame:

The ‘scientist’ world of order sits on the left-side of the frame, dealing with varying levels of complicatedness. The ‘artist’ world of unorder (to use Cynthia Kurtz‘s term) is on the right-side of the frame, dealing with inherent ambiguity and uncertainty – what the military would describe as a VUCA world. Complexity sits as a kind of blurry ‘cloud of unknowing’, somewhere in the middle.

And one of the main reasons why it’s so blurry is what we might call Einstein’s Dice, in homage to Einstein’s complaint above.

The boundary between the two sides is marked by what I’ve described as the ‘Inverse-Einstein Test‘. This is derived from another purported Einstein quote, where he’s alleged to have said that doing the same thing and expecting different results is insanity. That’s probably true in an ordered-world, but it’s not necessarily true in an unordered domain: there, doing the same thing may lead to different results, or we may need to do different things to arrive at the same results. The Inverse-Einstein Test runs that distinction kind of backwards: if we do the same thing and get different results, then by definition we’re in some kind of unordered domain. (Why it’s uncertain is itself likely to be uncertain, for a while at least… which is part of what sensemaking is all about, after all.)

The catch is that that boundary is itself often uncertain. It moves around, in response to what I’ve elsewhere termed ‘variety-weather‘:

— When the variety-weather is calm, the variety in the context will often remain stable enough for the ‘scientist’-style notion of control to work. These days, science and technology can often work with immensely complicated contexts – in other words, contexts with very high levels of variety – as long as the scale and structure of variety in the context remains the same.

— But whenever the variety-weather turns stormy, whenever the variety of the variety itself undergoes any kind of change – whenever the roll of Einstein’s Dice gives us a different value – then that complicated calculation may suddenly be shown up to be sadly simplistic: we hit up against complexity in the ‘artist’-style meaning of the term, where simple rules and complicated algorithms may no longer make sense, and where ‘control’ can itself be a dangerously-misleading myth.

Complexity is at the core of much of what we deal with in enterprise-architecture and the like: but it has those two fundamentally-different meanings, and hence two fundamentally-different sets of practices that we’d need to apply to it in each case. Yet if we aren’t able to keep track of Einstein’s Dice, we have no way to know whether the Inverse-Einstein boundary has moved, or which way it’s moved, if so – and hence no certainty about how to choose which way to work with the complexity within each domain. Tricky indeed…

So I’d suggest the practical implications for enterprise-architects are these:

- the ‘scientist’-style and ‘artist’-style perspectives on complexity are both valid, but apply best only in the appropriate SCAN domains – order (Simple/Complicated) versus unorder (Ambiguous/Not-known) respectively

- in practice, the term ‘complex‘ is probably best reserved for use only on the unorder side of the SCAN frame (a usage that also aligns with the SCCC-categorisation)

- use the Inverse-Einstein Test to identify which side of the order/unorder boundary applies in each current context

- use the same test to help keep track of Einstein’s Dice – the changes in variety-weather in the context

Comments/suggestions, anyone?

To simplify your characterization of the ‘IT/business-divide’; briefly:

– Business people think rationally and IT people think logically.

@B: “Business people think rationally and IT people think logically.”

I’d say it’s more ‘mode’ than ‘people’, but otherwise yes, agreed.

Thinking logically should always give results that are certain and true in terms of that logic; whether those results are useful or valid is another question entirely. The huge danger with logic-only thinking is that, by definition, it can only think within the constraints of the logic – it has no means within itself to assess the validity of the logic.

Which is ridiculous, there a certain complexities which cannot be simplified any further and are considered the lifeblood of an organization – The correct statement is … “Eliminate unnecessary complexities”

@C: “The correct statement is … ‘Eliminate unnecessary complexities'”

Agreed – the catch there is often around who gets to decide which complexities are ‘unnecessary’. 🙁 Consider the Puritans, for example, who decided that frivolity of any kind was unnecessary, and hence banned drinking, dancing, theatre, most games, most sports, and even Christmas itself. And Taylorism was (and still is) an attempt to remove all of the human complexities from business – only to discover that many of those complexities were a lot more necessary than they’d thought. :wry-grin: