Boundary of identity, boundary of control

What’s the boundary of the organisation? Boundary in what sense, and for whom? And how does this impact on enterprise-architecture and the like?

These questions came up for me a short while ago when working on an article on enterprise-architecture and ‘right-sourcing’, for The Sourcing Initiative, and again with my recent post on ‘Enterprise, organisation and the Olympics‘.

Organisation, enterprise and boundaries

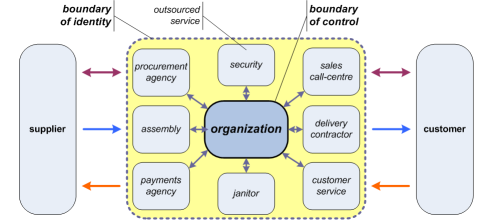

What came up for me there, in reflecting on that work, is that not only is there a crucial distinction between ‘the organisation’ and ‘the enterprise’, there’s also a related distinction that we need to draw between boundary of identity versus boundary of control. As with ‘enterprise’ versus ‘organisation’, those boundaries may sometimes coincide: but if we fail to understand that they’re different, and how they’re different, we can create an architecture that may run our organisation into very deep business-trouble indeed – yet without any apparent warning at all.

In other words, this ain’t a minor quibble about terminology and the like: this matters…

And where this matters most is in sourcing-relationships: ‘hands-off’ supplier versus insourcing versus outsourcing and so on. If you’re involved in planning any kind of sourcing-relationship – from call-centres to cloud-computing, from cleaning to catering to conferencing, and anywhere in between – then you need to know about this one.

First, a quick reprise on organisation versus enterprise:

- the organisation is a legal structure, defined/bounded by rules, roles and responsibilities

- the enterprise is a social structure, defined/bounded by vision, values and mutual commitments

The organisation’s boundary of control is the limit of the direct jurisdiction of the organisation’s explicit rules, roles and responsibilities. For example, the organisation is responsible for paying its own taxes, but is not responsible for paying its suppliers’ or customers’ taxes: those matters are outside of its boundary of control. Anything that’s beyond that edge, that boundary, the organisation can perhaps influence – and may want to influence – but it can’t actually control it. And that’s where thing can get messy…

Once again, this comes back to that crucial distinction between organisation and enterprise. To make sense of this one, though, we first need to jump sideways a bit, to another crucial distinction about perspectives, and in particular about inside-out versus outside-in.

Inside-out and outside-in

For most people within the organisation, looking inside-out at the business-ecosystem in which their organisation operates, the boundary of control is also the boundary of identity. The organisation is defined and bounded by what it controls: if it’s not under the organisation’s jurisdiction, then it’s not part of the organisation. Simple, explicit, objective: nothing complex about that at all.

But that’s not how most others will see or experience that boundary of identity. Looking outside-in, those others will hold a view that’s based more on the explicit or implied mutual commitments of the enterprise than than on the would-be rules and regulations of the organisation. From the outside, the organisation’s boundary of identity encompasses whatever people experience as ‘the organisation’. And because it’s about experience, not ‘fact’ – about the organisation in relation to the enterprise, rather than the organisation as such – this is often, and very definitely, not simple, not explicit, and not objective: in fact, about as complex as it gets. Hmm…

Perhaps the simplest example is a brand. It represents part of the public identity of the organisation – in fact may literally be a flag of the organisation. It presents a promise – a ‘value-proposition’ – in relation to the vision and values of the overall shared-enterprise. And the value of the organisation – its worth, in the terms of the enterprise and beyond – will depend in significant part on how well it’s perceived as delivering on that promise. Yet that’s all about how the brand is experienced, rather than solely on what the organisation does – outside-in, not inside-out. And much of that experience – all of it within the organisation’s perceived boundary of identity – may well be outside of the organisation’s boundary of control: for example, if the organisation’s chocolate-candy is presented as a half-melted mess on the supermarket shelves, that bad experience reflects not only on the supermarket but on the organisation’s brand as well.

Most people will manage their own views on identity versus responsibility pretty well: with that chocolate, for example, they’re more likely to blame the supermarket’s poor stock-management than the chocolate-maker as such. Even so, the bad experience it still impacts on the chocolate-maker – which is why that organisation, if they have any sense, will seek to influence the supermarket’s stock-management processes, even if they can’t control them. And those mechanisms of influence need to be an explicit part of the architecture – in effect, an explicit part of the organisation’s mechanisms of governance.

Yet whilst the chocolate example illustrates issues that can often be problematic enough in themselves, where it gets really messy is around sourcing – especially outsourcing.

Sourcing-relationships

In the classic fully-integrated organisation – such as typified by the Ford Motor Company or Standard Oil in the early 20th century – there is no external sourcing. In sourcing terms, the boundary of identity actually is much the same as the boundary of control – and everything that creates or delivers value is inside both.

These days, though, few organizations could create all of that value entirely on their own – or would choose to do so, even if they could. In almost all cases now, the tasks of value-creation will be shared with others, acting as suppliers or service-providers, through a wide variety of sourcing-arrangements.

In an insourcing model – of which the fully-integrated organisation is the extreme case – the respective service-provider is internal to the organisation: it’s within both the boundary-of-control and boundary-of-identity. The service-provider might well be a semi-autonomous business-unit – a customer-service call-centre, for example, or the archetypal ‘IT Department; but in principle at least, it’s aligned to and controlled by the organisation’s aims, intent and current strategy, because it’s inside the organisation’s boundary-of-control.

In the conventional supply-chain sourcing-model, each provider is deemed to be external to the organization: it’s beyond the organization’s boundary-of-control, but also largely outside of the organisation’s boundary-of-identity. In most cases, there’s no direct connection to organisational strategy and the like: the sourcing-relationship is strictly transaction-based, according to explicit contract.

Yet even this ‘hands-off’ approach is not as simple as it seems, or as most of the players would no doubt hope. For example, consider even a straightforward linear sequence of provider/consumer service-relationships, such as in the stereotypic SCOR sequence from supplier’s-supplier to customer’s-customer: there’s a hands-off relationship between each of the players in the sequence, yet to the customer at each stage, all of the previous suppliers will seem to be included within their own immediate supplier’s boundary-of-identity.

For a simple example, imagine you’ve bought a new car, and the radio doesn’t work properly. The actual cause is a faulty electronics component that a factory in Thailand supplied to a assembly-plant in Taiwan that built a sub-assembly for the German manufacturer of the radio that the car-maker in Australia fitted into the car: but as far as you’re concerned, it’s a problem for your local car-dealership to fix. The contract-relationships help to sort out who’s responsible for what, though some tricky architectural and legal problems can arise when the contract doesn’t cover enough of the scope, and hence key themes drop into the ‘it’s everyone’s Somebody Else’s Problem’ domain. But to you, all of that should be hidden behind your contract about ‘service of delivered working car’, and hence within the scope of the dealership’s boundary-of-identity: it’s their problem, not yours, and you’re sure of that fact!

In an outsourcing model, the provider-relationship sits somewhere on a spectrum between the two extremes: neither fully internal, as in insourcing, nor fully external, as in the classic supply-chain. This can work very well, but the danger is that we risk getting the worst of both worlds – as many organisations have now found out to their cost.

And the best way to understand why outsourcing can be so problematic is to assess it in terms of boundary-of-identity versus boundary-of-control. The services delivered must in effect be ‘internal’ to the organization – especially as seen from the perspective of ‘outsiders’ such as the organisation’s customers; yet it’s operated partially or entirely outside of the organisation’s control. This is actually a key source of outsourcing’s value to the organisation: it doesn’t have to invest in the service, it doesn’t have to pay much attention to the day-to-day running of the service – it just happens, it just works. But the catch is that when it doesn’t work, it’s the organisation that gets the blame – not the service-provider. And the reason is that although the service is outside of the organisation’s boundary-of-control, it’s inside the organisation’s boundary-of-identity – and to an aggrieved customer of the organisation, it’s the boundary-of-identity that is all that matters.

The boundary-of-control should be easy to identify, of course: no problems there. Yet there are also several almost-as-simple tests we can do to identify whether something – some service – is either ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ the boundary-of-identity. For example:

- Is it using your name? – if a call-centre makes calls on your behalf, using your organisation’s name, it’s inside the boundary-of-identity.

- Does it use your signage or branding? – if a delivery-contractor has your logo on his van, or a debt-agency acts on your behalf with your company’s name on their letterhead, it’s inside your boundary-of-identity.

- Does it take place on your premises? – to the general public, a janitor or security-guard in your shop or your offices is within your boundary-of-identity.

- Does it deliver a service that purports to be yours? – your web-host service, your mail-campaign service, and your social-media response-service, will all be perceived as inside your boundary-of-identity.

And whatever it is, and whoever it is that does the work, if it’s inside your boundary-of-identity, it’s your reputation that’s on the line.

Let’s illustrate this with a first-hand example from earlier this morning. As is all too usual here, the phone rings, with someone saying first “I’m not trying to sell you anything”, and then proceeds to try to sell something – in this case, solar panels (the current most-popular scam amongst the call-centre folks, it seems). It’s my elderly mother who answers the call; and since she’s somewhat deaf and won’t wear a hearing-aid, she can’t make sense of what the guy is saying. She tells him so, politely, and puts the phone down. Ten seconds later, he rings her back, complaining at her that he thinks she’s “being very rude” by putting the phone down – and then goes straight back into his sales-script, telling her that she’s “missing out on a once-in-lifetime opportunity” and all the rest of the usual garbage. Needless to say, my mother was pretty upset about this; she was almost in tears when she finally did risk putting the phone down again. Believe me, I won’t buy anything from Skyline, or whatever that solar-panel company was called…

But note this: this idiot was an employee of the call-centre, but doing enormous damage to the reputation of the call-centre’s client – not the call-centre itself. It was an outsourced service: outside the organisation’s boundary-of-control, but inside the organisation’s boundary-of-identity.

Unlike an insourced service, outsourced services are not under the organisation’s control. But because it’s partially or fully inside the organisation’s boundary-of-identity, the relationship is not as straightforward as the ‘hands-off’ contract-based transactions in a fully-externalised supply-chain. Instead, it sits in an awkward space somewhere halfway between: it needs the transaction-type separation, but it also needs the strategic integration into the organisation and its relationships with the broader enterprise. And getting that balance right is not simple…

Architecture implications

All of these issues will arise not only in organisational system-architectures and the like, but also in customer-journey modelling, process-mapping, business-continuity planning, anticlient-risk management and much else besides.

One of the complications here is that any outsourced service is serving two distinct shared-enterprises:

- the shared-enterprise of the service itself – for example, a security-guard would be in an enterprise revolving around safety and security

- the shared-enterprise of the service-client – for example, a retail shop is an enterprise about openness and opportunity

There may well be conflicts and priority-clashes between those two distinct enterprises – conflicts that must be identified in the outsourcing-arrangement, and contractual and other mechanisms put in place to manage them.

Note too that many (perhaps most) outsourced-service providers base their business-models on economies-of-scale – in other words, they’ll have multiple clients. Implications here include:

- the service-provider needs to balance all of the differing shared-enterprises of their clients

- the staff of service-providers, and the services themselves, need to be aware of and switch appropriately between each of the respective shared-enterprises for each of the clients

Given that different trade-offs and different values-priorities may apply in each case, this can be a very real challenge for service-providers.

Much the same applies in the opposite direction with themes such as auditing and compliance: the client-organisation must demonstrate compliance via the service-provider, but the service-provider may need to demonstrate compliance with multiple and maybe-conflicting standards and audit-schemas. Again, a very real challenge.

For the client-organisation, alignment with shared-enterprise is a key driver for strategy – which in turn includes themes such as sourcing-arrangements. For the service-provider, this will mean:

- aligning with and engaging with different strategies for different clients, all undergoing different dynamics, different drivers and different rates of change

- ensuring that there is no ‘blur’ between clients and their strategies – and especially so where the service-clients are competitors of each other, with all the concomitant concerns around conflicts-of-interest and the like

Most consultancy-providers have had long practice at maintaining ‘Chinese Walls’ between their service-clients – but the governance-mechanisms, and even the awareness for the need for them, are less common amongst many other types of service-providers. Several cloud-service providers have already fallen foul of ‘leakage’ between clients in not-so-secure online-systems: it needs to be understood that is an architectural problem that needs to be addressed at architectural level if it is to be appropriately managed – especially over the longer term.

A quick summary again:

- the organisation’s boundary-of-control is the limit of its direct jurisdiction – typically as described in an ‘inside-out’ view, looking outward from the organisation

- the organisation’s boundary-of-identity is determined by whatever others see ‘as’ the organisation – an ‘outside-in’ view, looking inward towards the organisation

- outsourcing-arrangements usually sit somewhere outside of the boundary-of-control, but inside the boundary-of-identity

- contracts and relationships for all sourcing-arrangements – and especially for any kind of outsourcing – need to address not only the direct transactions, but all of the ‘market-cycle’ issues before and after those transactions as well, at least over the full lifecycle of the sourcing-arrangement, and probably beyond

As usual, I hope this helps: comments / feedback / suggestions, anyone?

Perfectly brilliant! Clarifying! On your last figure, how about (3-dimensionally speaking) laying the dashed outlined Organisation box over horizontally (along with the Supplier/Customer). Then grab the solid outlined Organisation box and pull it up vertically above the rest of the structure, retaining the connecting lines which would now angle down. Then, organize the remaining boxes within the dashed outline box according to an operating Enterprise of value flows. Perhaps one could pull these remaining boxes up vertically into an intermediate level showing their management of the flows (?). Where are my 3-D glasses when I need them?

Uh… thanks very much, Myron, though will admit that my addled old brain is struggling to picture your 3D-view… 🙁 If I’ve understood it properly, then yes, it makes a lot of sense: but I’d have to admit it’s a big ‘if’ here… 🙂 Any chance I could get you to have a go at visualising it in some kind 3D-graphics package?

Actually, I’ve been thinking about getting a 3D package just to do this type of stuff. However, all of the modeling ‘language’ packages are 2D. So, it will have to be a CAD package. I will pursue this with more vigor…

One additional dimension to the problem – time. Over time, organizational structures change, which in turn cause changes in the boundary of control. That may mean that the contract you placed with a service provider may now be fulfilled by a second tier service provider. From the control perspective, the organization needs to ensure that the contractual conditions placed on the supplier are transferred to the second tier.

Long term data retention shows up these problems quite painfully – where long term may be as short as a few months. Already organizations have lost access to their data because the supplier hosting their data was closed down for hosting illegal material for another client. On the cloud, where perspectives are relatively short term and many organizations are likely to go under or be bought up, this will pose an “interesting” (as in the Chinese curse) problem. The best guidance on this comes from Audit and Certification of Trusted Digital Repositories (http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=5651), which considers the contractual side of letting someone else look after your information.

Hi Sean – thanks for bringing up one of my own personal hobby-horses, about time, and especially impacts over the longer-term.

You’re absolutely right there, of course, on all of your points above: very good points indeed.