How anti-clients happen (and what to do about it)

Are there any anti-clients for you in your enterprise? Who are they? How did they turn so actively against you? And what can you do about it, and them, in the design and implementation of your enterprise-architecture?

Who are anti-clients?

To make sense of this, we need a quick recap of the Market Model:

Our organisation’s clients, prospects and ex-clients are part of our direct market-context: they interact, may interact or did interact in the value-streams for our services’ main-transactions. However, the organisation’s business-context extends beyond the market, out into a much broader shared-enterprise, connecting via values (plural) rather than value (as in a supply-chain value-stream).

Anti-clients are a specific category of non-clients in that they don’t engage with the organisation in that direct market-space (though they may formerly have done so – a point we’ll come back to later): they’re ‘out there’ in the broader and more indirect enterprise-space. In that sense, anti-clients are significantly different from ‘the competition’ and suchlike, who do operate within that direct market-space. An anti-client is someone (or some entity) who shares the same or similar enterprise-vision, but who actively opposes the ways in which our organisation engages in that enterprise.

The reasons for that opposition are many and varied, but in some ways the reasons themselves often don’t matter all that much. What is important is that we don’t merely ignore the fact of that opposition – as so many organisations try to do – but instead acknowledge that the opposition exists, and, wherever practicable, try to engage with it as honestly and respectfully as we can. If we don’t, the anti-client opposition will continue to fester away on what may seem to be only the ‘far-out’ edge of the enterprise, but can suddenly ‘infect’ the active market-space and impact the organisation’s business. And in the days of social-media, that kind of anticlient-‘infection’ may represent a kurtosis-risk that’s big enough to kill the company: in other words, not something that’s wise for us to ignore…

There are two main drivers for why people become anti-clients: an inherent values-clash, and a sense of betrayal. These are not mutually-exclusive – in fact things can get seriously messy when they coincide. Yet it’s useful to treat these as somewhat distinct, not least because we would usually address them through different mechanisms within the organisation.

An inherent anti-client is someone who is in the same enterprise-space – often with no choice but to be in the same space – whose values, morals and/or ethics collide those of the organisation, either in terms of intent or, even more, in terms of action. The feeling or assertion is that the organisation is inherently ‘wrong‘ in what it does or how it does it. For example, if you’re doing logging or minerals-exploration in a wildlife-reserve, you will have inherent clashes with environmentalists or indigenous peoples; if you run a family-planning clinic, you will have inherent clashes with ‘pro-life’ activists. And this will remain so whether or not the current law upholds the organisation’s activities: it’s a values-clash (enterprise), not a legal-clash (organisation).

A betrayal anti-client usually starts out in the market-space, as an active client. At some point, for any of a vast array of possible reasons, their experience is that the organisation has been ‘unfair’ in its relations with them personally, or with others that they know. They want the perceived unfairness to be acknowledged and addressed: the sense of betrayal will continue to grow for as long as these concerns – from their perspective – are not appropriately addressed. Probably the most common example in business is unresolved customer-complaints, for which the classic betrayal-anticlient fightback is the song ‘United Breaks Guitars‘. That feeling of ‘unfairness’ is frequently described by betrayal-anticlients in terms of ‘abuse‘ by the organisation – which in technical terms, as ‘evasion of responsibility‘ by the organisation, it often actually is.

Perhaps the key point here is that this is primarily about trust – or, more specifically, lack of trust, and/or loss of trust. Without some means of (re)creating trust, there is no way forward – and all too easy for it to become a (literally) vicious-spiral.

One of the other crucial points to understand here is that feelings are facts, whereas interpretations of feelings are not facts – they’re just interpretations. Far too many people get this point the wrong way round – and that’s when and why things tend to turn seriously wicked…

Inherent-anticlients usually try to remain detached from the organisation, and betrayal-anticlients usually aim to become ex-clients (market) or non-clients (enterprise), where their potential for impact may often be reduced. But if they are forced into active relationship – such as where the organisation is physically in their homespace – or forced to become or remain active-clients – such as in a monopoly context – the sense of ‘wrongness’ or ‘unfairness’ will be continually reinforced, and has nowhere else to go. Such ‘trapped’ anticlients can act much like cornered wild-animals: if ‘flight’ is not available, and ‘freeze’ (ignore) doesn’t work, then the only remaining option is ‘fight’ – and since the underlying drivers are emotional, not ‘rational’, that fight can extend far beyond apparent reason, even ‘to the death’ and worse.

Hence why these are not issues that we can casually ignore in business: if we’re not careful how we handle them, and fail to understand what’s actually going, they can explode from any seeming unexpected-direction, without any apparent warning, yet bring enormous destruction in their wake. In short, not trivial…

All of which might still seem a bit abstract. So let’s put this into real-world perspective, with a live issue that’s affecting me personally, very hard, right now.

[Update: In case anyone gets too hung up about this, the section that follows is merely an example of typical drivers for an anticlient-relationship, and the kind of feelings and mindset of the anti-client. You can ignore the specifics if you want, because they’re really not all that relevant for most people: what matters is the description of the feelings, because those types of feelings are the core facts that you have to deal with in architecture and design for mitigation and resolution of anti-client issues. Seriously, believe me, that section below is trivial by comparison with what’s happening for and with some of your own organisation’s anti-clients: this is just a relatively-minor example to give you something to work with, that’s all. The most important part of the post is the ‘how-to’ section that follows this one. Okay?]

A first-hand example

If you’ve read this blog or read my earlier books, you’ll see that I used to be a strong promoter of the Cynefin framework and its use in enterprise-architectures. Not any more: far from it, in fact. Very far from it, over the past couple of years or so. So how and why has this happened?

The core of the disagreement centres around the definition, interpretation and application of the term ‘Chaotic’ within sensemaking and decision-making. Cynefin asserts that ‘Chaotic’ is solely a subset of and feeder into ‘Complex’ – the realm of complexity-science and suchlike – whereas I’ve been insisting that it needs to be viewed as something separate and distinct from Complex. At first glance, that sounds almost as abstruse and absurd as one of those bizarre ‘how many angels on a pin-head?’ arguments: but in practice that distinction between ‘Chaotic-as-a-subset-of-Complex’ versus ‘Chaotic-as-itself’ has huge implications in enterprise-architecture practice, around design for inherent-uniqueness, ‘market-of-one’ and many similar real-world concerns.

Which means there’s a disagreement. Sure. So what? Why’s it such a big deal? Why not just agree to disagree, and leave it at that?

Reality is that I can’t just ignore it, however much I might want to do so. Cynefin is one of the dominant models in the sensemaking space: and sensemaking is a context I must address in my work in enterprise-architectures, as an inherent part of that work.

I’ll admit I was a bit slow, because it took me some five years or so to realise that I had a fundamental disagreement around how Cynefin handles the Chaotic, viewing it – and everything else – solely in terms of its relationship to a specific model of the Complex. To me Cynefin seems to be ‘Complex-centric’ in a very similar sense to the way in which TOGAF and Archimate, for example, are inherently IT-centric – and hence with very similar problems and risks for the enterprise-architecture. To me, ‘anything-centrism’ is very bad news for an enterprise-architecture: not just a ‘bad idea’, but ethically ‘wrong’, because it conceals a very high risk of damage to the enterprise. In that sense, I’m an inherent-anticlient for anything that promotes anything-centrism. Hence some fairly inevitable values-clashes in my work in enterprise-architecture…

My disagreements with Open Group and the like around IT-centrism were pretty intense for a while too: but there was a willingness on both sides to work through it, and there is now, I think, a general if perhaps sometimes grudging agreement that I was right to challenge them on it, and that a non-IT-centric approach to EA is the right way to go.

Not so, unfortunately, on the clash with Dave Snowden, the main promoter of Cynefin. His preferred style of debate is highly combative: as he’s said many times, he likes to “dish it out” to anyone who disagrees with him. It’s a style that may work well for him, but it doesn’t work for me at all: I don’t like it, I’m no good at it, and it feels ethically wrong to engage in that kind of relating. Result: I ‘lose’, whichever way I play it. Hence it feels not just ‘wrong’ (inherent-anticlient) but ‘unfair’ as well (betrayal-anticlient). And I’m trapped: I’m stuck in the same concept-space as Cynefin, whether I like it or not. Perhaps not surprising, then, that it quickly turned nasty – and has become steadily worse and worse over the past few years, with no end-point in sight.

If you want a direct illustration of how and why I’ve now become such an intense anti-client in regard to just about anything Cynefin, just take at look at this comment that Dave Snowden placed yesterday on a colleague’s website:

Tom’s description of Chaos are to my mind what the literature describes as Complex; I suspect he is using a common language definition rather than the scientific one which is fine but which I also think explains his confusion.

And also this Tweet yesterday morning:

RT @snowded: The comment deleted by @tetradian Every 6 months he repeats the same errors & deletes response Can’t cope? #entarch http://t.co/VYh2b16r

There, in just two lines, we have the unsubtle insinuation that my work is ‘unscientific’, that I’m unable to understand ‘the literature’ (unspecified), that I am ‘confused’, that my analysis contains ‘errors’ (unspecified), and that I’m ‘unable to cope’.

(It’s possible that may not be how he intended it, but that is how I interpret it now: that’s how it feels.)

Elsewhere you’ll find many similar assertions from him that my work is a ‘hash-up’, ‘illegitimate’, ‘of no validity’ and much, much more of that ilk, repeated and repeated, over years and years and years.

(If you wonder why this hurts, read Snowden’s assertions as if they were said not about someone else’s work, but about you and your work, day after day, month after month, year after year. Makes a difference, doesn’t it?)

Evidence offered by Snowden for any of his assertions? None.

Acknowledgement of the possibility that my analysis might indeed be correct, and that the confusion and errors and incompletions might indeed be in his work, not mine? None.

Awareness or acknowledgement that there are very valid reasons why I delete his comments on my blog? None.

Nothing. Just the archetypal old-school IBMer’s indulgence in insinuation, smear, denigration and FUD.

That’s how it feels for me right now. And people seriously think there’s any point in my attempting to do proper debate with that?

Pah! To hell with it…

That’s how it feels, anyway: and feelings are relevant facts in this type of context – perhaps even more so than supposed ‘objective fact’. And to be blunt, I’m more than just a bit angry about it all, no trust whatsoever, and those feelings have festered for far too long a time. Definitely an anti-client, then… both an inherent-anticlient and betrayal-anticlient, because to me all of this not only feels ‘wrong’ (collective/ethics), but vastly ‘unfair’ (individual/abuse) as well.

So: what next? In terms of this specific mess, probably nothing that we can usefully do about it right now. My problem, really: that’s it. Deal with it. Oh well.

Yet if we sidestep all of that all-too-personal misery for the moment, there are some general principles that arise from this example, about handling of anti-client issues, that are directly applicable in enterprise-architecture and design: and it’s probably worthwhile exploring those before moving on.

Application in enterprise-architecture

To get clear from the ‘personal stuff’, let’s go over the basics in abstract again:

- anti-clients become anti-clients because of values-clashes with the organisation and its perceived intent and/or actions within the scope of the shared-enterprise

- inherent-anticlients tend to have little or no direct engagement with the organisation’s main business-transactions; the values-clash tends to be around abstract, collective, and perceived ethics or morals – a perception that what the organisation is doing is inherently ‘wrong’

- betrayal-anticlients tend to be or have been engaged directly with the organisation’s main business-transactions; the values-clash tends to be around concrete, personal and perceived actions or inactions – a perception that what organisation is (not) doing is palpably ‘unfair’

- people may be or become both inherent-anticlients and betrayal-anticlients, with a variety of dynamics between the two forms

- anticlient-relationships become more intense whenever the anti-client feels ‘trapped’ in the context – especially where the relationship is experienced or perceived by the anti-client as being ‘rigged’ in favour of the organisation

- [Update (thank you Martin Howitt!): anti-clients are not necessarily external to your organisation: for example, there is a significant risk that employees will develop anticlient-type relationships with others in the organisation, and with the organisation as a whole, which inherently tend to become intense because the employee is in effect ‘trapped’ within the organisation; the intensity, and risk, increase with increasing dysfunctionality of the organisation – see the SEMPER diagnostic for more details on this]

- all anti-clients represent variously-significant kurtosis-risks for the organisation

- the core issue in all cases is a lack of trust

- if nothing is done, the default is a tendency to fall into a vicious-cycle of ever-intensifying distrust, with an ever-increasing risk of damage to all parties (‘everyone loses’)

- anti-client relationships and risks can be eased or resolved by systematic attention to values-themes and to trust – how trust is created or destroyed in the organisation’s interactions with others

To explore that last theme – about trust created or destroyed – it’d probably be useful to do a recap on the Market Cycle, or Service Cycle:

In a conventional transaction-oriented perspective, the business-relationship begins by gaining the attention of the prospect, and ends when the organisation achieves its own aim in the transaction. This is an ‘inside-out‘ view of the market, with clients and others seen only in terms of their relationship with self (the organisation).

The danger is that this is only a subset of the full service-cycle, the latter of which we tend only to be able to see from an ‘outside-in‘ (client-oriented) perspective. The outer parts of the cycle relate to trust and relationship: trust underpins relationship which provides the ground for conversation, and so on. If there is no trust – which is exactly the issue in anticlient-relationships – then there is no way for the cycle to get started; if trust is not actively renewed – by ensuring that the transaction is completed in terms of the client‘s success-criteria – then trust itself is eroded, such that eventually no new cycle can be started. And when that happens, everyone loses.

Note too that some interactions never reach a conventional transaction as such, but still need to be completed in terms of the client’s success-criteria: in effect, it only goes through the outer part of the loop. In the earlier stages of client-relationships, and in all non-transaction relationships, this outer-loop cycle is the norm rather the exception.

The core requirement for all of these interactions is that trust must be created and maintained if the cycle is to function successfully from anyone’s perspective, especially over the longer term.

And the way we build trust, and maintain trust, is via the vision and values of the enterprise – and explicitly demonstrating the organisation’s alignment to those values.

To work with inherent-anticlients, the typical core mechanisms that we’d use are essentially the same as those for investor-relationships. (This is because they are ‘investors’ in the organisation, whether they want to be or not: the forms of value invested are rarely financial, but it is explicitly investment nonetheless.) The way to build trust is to identify and then leverage shared aspects of enterprise-vision and/or shared-values.

To work with betrayal-anticlients, the typical core mechanisms that we’d use would be embedded in and/or an extension of the existing customer-service capabilities. (This is because they usually are customers or clients before the perceived ‘betrayal’ kicks in.) The way to build trust is to ensure that the person first feels heard, and then demonstrate through action conformance to declared enterprise-values.

Beware that enterprise-values are a definite two-edged sword here. In effect, the organisation’s declared-values represent the overall value-proposition of the whole organisation in respect to the shared-enterprise: if actual-values (enacted values) do not align with espoused-values, this will destroy trust, often irreparably. In short, don’t declare a value to be significant to the organisation unless it does demonstrably pervade every aspect of the organisation and its architectures – otherwise the malconformance will come back to bite you hard in terms of loss of trust and increased anticlient-problems and -risks. (To use Kevin Smith‘s term, value-malconformances represent a huge source of unidentified and unacknowledged Enterprise Debt.)

Social-media monitoring is an often-essential method to track and intercept potential anti-client problems before they spiral out of control. For example, here are a handful of (de-identified) Tweets that I tagged as potential anti-client examples over the past few months:

- Ryanair emails me to say it’ll debit my card with increased Spanish departure tax. BA will absorb it. If only I had a choice to Reus. // Does anyone, if given a choice, book with Ryanair?

- So Ryanair tell me they will debit my card to cover new Spanish airport tax. But not by how much. So I just trust Ryanair, right?

- ‘the volume of hazardous waste produced by suspected Apple Inc. suppliers was especially large” http://bit.ly/NFKB0a

- After the third f/u in one day by @united, you begin to understand it’s a pattern and a business philosophy, not passenger bad luck. #fail

- Ok Marriot and Starwood…I’m not paying $18 4 an on demand movie when I can download 1 4 $5 on iPad. Wake up 2 reality.

- Too much airline maneuvering this week. Fortunately at @SouthwestAir there is a will & an eventual way; at @United, there is simply no will

- Airline rants, cont’d: It’s actually shocking to compare what people tweet about @SouthwestAir (good!) vs @United (abysmal) #whatsaschedule

- Apple refuses to carry a book because it mentions amazon http://bit.ly/PWCVtI

- Copenhagen Airport is not designed for human needs: only very few toilettes and places to sit near the gate

- Forget UnitedBreaksGuitars: How about @United loses 10yr-old and doesn’t care? http://bit.ly/R9C1N7

- Today I have seen “improvements” from American Airlines and Google that worsened the quality of my user experience #ux #ia #ixd

- Wow – Sales Incentives at Staples Draw Complaints — The Haggler http://zite.to/OjuWbF

- Most annoying forms of Web adverts: 1) Pop-ups when you mouse over a word…. 2) Videos that start blasting as soon as you load a web page

- Does @telstra make a special effort to have such bad customer service? Is there a selection process for incompetence nurtured with training?

Some of the common themes here: betrayal of expectations, perceptions of poor value and misuse of ‘captive market’, loss of trust, lack of trust, and even disgust and dismay. You’ll also see one organisation (Southwest Airlines) specifically singled out as a contrast of ‘good’ versus ‘bad’. There’s a lot that can be learnt from this, especially in terms of need for proper vision-based value-propositions, viable customer-service design and need for live customer-available information (another very common complaint about airports and airlines).

One theme that rises time and again is that one of the quickest and most powerful ways to restore trust is simply to ensure that the person feels ‘heard’ – that their complaint is acknowledged, listened-to and respected. In a surprising number of cases, that’s all that need be to shift someone out of an ‘active betrayal-anticlient’ mode, and into concrete engagement in mutual-responsibility for what happens next.

With care and proper system-design and system-operation, most betrayal-anticlient relationships can be resolved, even to the point of becoming a virtuous-cycle trust-relationship. The same is true – or true in part – of some inherent-anticlient relationships: Walmart’s engagement with sustainability-activists is one well-documented example. However, the enterprise-architecture must acknowledge that all anti-client relationships will carry some wicked-problem components, because of the inherent and in some cases irresolvable value-clashes.

One of the first requirements in architecture-development for anti-client concerns is that it’s essential to identify the respective values, expectations and value-clashes. Nigel Green’s VPEC-T (Values, Policies, Events, Content, Trust) is one framework that’s especially useful for this purpose.

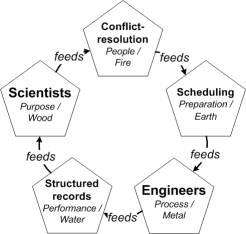

Wherever wicked-problem components occur, it’s also essential to design explicit mechanisms for arbitration or conflict-resolution. One of the keys here is to make it clear that the clash itself is ‘no-one’s fault’: it’s inherent in the relationship, not the people. (It definitely is ‘someone’s fault’ if that ‘someone’ fails to uphold the espoused values of the enterprise: identifying that that has occurred, and what to do about it, is one of the core responsibilities for the arbitration mechanism.) There’s a brief description of such a mechanism in the post ‘Unbreaking‘, about a wicked-problem between scientists and engineers in a research-facility:

Note too in that example another key characteristic of success here: everyone wins. In this specific case, the overall resolution design included improved scheduling (which supported the engineers’ need for better predictability in their very time-constrained work-context) and better structuring of the engineers’ work-records output (which supported the scientists’ need for re-usable data for analysis and experiment-design). The reason why ‘everybody wins’ is such an important design- and operations-principle is that it reduces the key driver that creates betrayal-anticlients: the sense that something is ‘unfair’.

Anyway, more than enough for now: hope you find something useful to make a start on from all of this.

Over to you, perhaps?

Hi Tom

interesting approach. You asked me on Twitter if this was useful in the world of local government which is where I work, and the short answer is yes, but with some caveats.

Firstly, we have a lot of anticlients in the public sector. Pretty well anyone who didn’t vote for the incumbent administration, for starters: some employees: partner organisations (private, public or voluntary sector): some politicians. That’s the short list!

I’m boiling down your analysis to just the key words here, for reasons which I’ll go into in a bit:

1) maintaining trust is the key thing: yes. Public organisations must say what they think, and do what they say, and they must be a safe pair of hands in the most critical circumstances (think the safeguarding of children, or a big traffic accident).

2) ensure that people feel heard: this is actually something that a lot of energy is spent on in my experience. We need to do better and social tools can allow for better dialogue.

3) identify values, expectations and value-clashes: yes and no here. There’s a problem of managing a HUGE number of opinions on an enormous range of topics, and resources are scarce.

4) explicit mechanisms for arbitration or conflict resolution. These exist at the citizen level (planning appeals) and at the political level (scrutiny). Probably we could do better.

The problem with using this analysis, like most enterprise architecture “stuff” in local government is the trade-off between complexity and scarce resources. My organisation only has a handful of people who could do enterprise architecture and we are generally bogged down with other stuff. As a result I favour tools and methods that oversimplify things as otherwise I can’t get the coverage that I need, and use my network ruthlessly to crowdsource approximations of the necessary artifacts.

Martin

Great points, Martin – many thanks.

One thing that can help mitigate and resolve 3) is to be much more explicit about the values and value-priorities of the organisation. There’s a lot to explore there, but it’s probably best done offline – set up a Skype-session somewhen, perhaps?

On “a lot of anticlients in the public sector”: well, yes. 🙁 It may be useful here, though, to distinguish between anticlients and ‘competitors’ – quite a lot of what might seem to be anticlients would more accurately fit in a ‘competitor’ category, for which the tactics are somewhat different (it’s in the ‘market’ rather than the broader-enterprise: for example, we can emphasise law and the dynamics of majority-rule electoral-systems rather than rely solely on values). More to discuss, of course! 🙂

And Martin, you’re right, in the post I forgot to mention employees – they’re often the most conflicted anticlients of all, because many them really are ‘trapped’ in the context with no apparent way out. That’s why Bob Sutton’s work – as in ‘The No-Asshole Rule’ and ‘Good Boss, Bad Boss’ – can be so usefully re-leveraged as guidelines for broader anticlient-work, because it’s essentially the same issues playing out, but in an ‘office-politics’ arena.

Always a pleasure to read you Tom. It’s been some time that I couldn’t find time to do so… But, I enjoyed this one that I (as often) could map to my own experience.

BR

/Emeric

Thanks, Emeric. That’s really my aim here – to do stuff that’s useful.

Often the most useful things are those that are ‘obvious’ yet that we don’t actually notice and realise how important than are until someone brings it to our overt attention: I’ve had that often from other people’s writing too. Hope it helps in practice, anyway.

Gday ugly!

I don’t pretend to understand all the anti-client concepts listed here but re “all-too-personal misery” and the opinion of others whom disagree with you, as someone who has worked directly with you NOTHING SUCCEEDS LIKE SUCCESS.

Tools you built in 2005-6 are still being maintained down under, Open Group are coming around and you are learning too.

Yes you’ve made mistakes, no not everything you blog is perfect and no your works have not created world peace or your first $100 Million (AUD) BUT stop and look at ALL the positives (I was going to list those I know of then worried the field would not cope) so that the “all-too-personal misery” is put into the minor space in your life that it should be.

Hi there oh beauteous one! 🙂

[Quick note for others: this is a silly piece of banter that’s been going on between Peter and I for the best part of a decade – fairly typical of the kind of ‘not-insults’ that do help to reduce anti-client risks in the workplace. 🙂 ]

Yeah, you’re right, of course: in factual terms, I do have a lot to celebrate – and many thanks for reminding me of that, because it really does help towards getting me out of those ‘downer’ times/spaces. Yet the point here is that in these kinds of spaces, feelings are facts in their own right, and very often do take effective priority over supposed ‘objective fact’. (If you doubt this, notice the very low priority of concrete fact, relative to feeling and emotion-based pre-decision, displayed across the US at present in relation to their upcoming presidential election…)

To take it out of the personal here, yes, it’s true that in more objective terms ‘the all too personal misery’ is “the minor space in your life” and so on: but it doesn’t feel that way at the time. The practical problem – and there’s masses of psych-research on this – is that unless the feeling can be acknowledged in some way, there’s no way to move on: the feeling festers, and everything is interpreted in terms of the ‘pre-filter’ of the respective emotion. That’s what drives the vicious-circle downward-spiral. [Interesting: it’s remarkably difficult to describe this in words alone: probably easier to dance it, or something like that? Odd, anyway…] In practice, we need first to deal with the feeling as feeling – otherwise there’s literally no access to ‘a sense of perspective’ and suchlike that could be used to break the downward-spiral.

To take it further out of the personal, and bring it to somewhere that has general value in enterprise-architecture around anti-client issues:

— feelings are facts, especially in anti-client and related issues: if we fail to design for that fact (as in many so-called ‘Customer Service’ systems), we will automatically reduce the efficacy of and increase the overall enterprise-risk for that system

— presenting ‘fact’ as a response to emotion doesn’t work: not only is it a ‘chalk and cheese’ mismatch, but it actually further inflames the emotion because it reinforces the sense of ‘not having been heard’

— responding to emotion with direct counter-emotion (“you’re wrong”, “you shouldn’t feel that”, etc) also further inflames the emotion, usually on both sides – we need to respond to emotion with emotion, yet with some kind of indirect ‘sideways’ pull

A good example of the later is the classic arbitration-court system, where the conflict between two warring parties is mitigated by the ‘sideways’-pull of surroundings and rituals that do respect the emotion yet also interpose the feelings of respect of the court as a ‘higher’ authority. (Note that this doesn’t work when the court itself is an active representative on behalf of one of the players: instead, it very much reinforces the sense of entrapment in a rigged ‘game’. That’s how revolutions start… :wry-grin: )

This is also one reason why I’m so against the concept of ‘rights’: purported ‘rights’ pretty much automatically bring emotion into direct conflict with emotion, yet also prevent any alternate means to break the deadlock. When everyone has the same ‘rights’, there’s no ‘fact’-based option to move on and no ‘sideways’-move available, hence often the only way out is a seriously-dysfunctional ‘might is right’; and when the ‘rights’ are asymmetric, the party with lesser ‘rights’ will undoubtedly resent their entrapment in what is by all apparent definition, a ‘rigged game’. Either way, everyone loses – especially over the longer term. By contrast, responsibility-based models do enable ‘sideways’-moves such as those in the classic Chinese Five Element framework that we used in the scientists-vs-engineers example at the research-lab. That way, everyone wins: big difference.

[Once again I’ve had to delete a comment posted here by Dave Snowden.

(I have no idea why he seems utterly incapable of understanding that the word ‘No’ does actually mean ‘No’, and that his behaviour here over too many years means that he has long since forfeited any reasonable right of reply. But that’s his problem, not mine: I will stick to my explicit much-reiterated policy on comments and commenters on this blog, and leave it at that.)

I have no qualms whatsoever in agreeing that in certain cases he might want to comment on what I’ve written. But not here: as I have said many times now, that stipulation is not negotiable.

I don’t intrude on his weblog; I would much prefer it if he didn’t endlessly try to impose himself on mine, where he has been told many, many times that his presence is no longer welcome. Sigh…]

[Given the above, I perhaps need to reiterate yet again that the middle-section in the post above is intended for illustrative purposes only, as an example of the emotion-based drivers that underpin anticlient-relationships. It describes feelings, and illustrates the way in which those feelings colour one’s interpretations. That is all. It explicitly describes subjective-‘truth’, not purported ‘objective-truth’ – a crucial distinction in all such contexts.

To repeat de Bono’s classic aphorism, “Everyone is always right, and no-one is ever right”: everyone is ‘right’ from their own perspective on a context, but no-one ever holds the ‘objective-truth’ about that context. The thinking-error of assuming that “I am right, therefore all others are wrong” is a classic source of anti-client problems. For organisations, this often comes out in ‘inside-out’ thinking, assuming that others exist only in relation to self – hence Chris Potts’ important warning that “customers do not appear in our processes, we appear in their experiences”.

A much stronger anti-client example, included in the list in the third section of the post, is the ‘United loses 10-year child’ story described so well by Bob Sutton and others. The problem with that example is that it’s actually too strong for the purpose here, and in some ways also too ‘distant’, impacting a near-abstract ‘Other’: hence why I chose to use an example that’s direct and immediate and personal, because I can describe with some precision the emotions and feelings and feelings involved, and how they get in the way of the kind of misplaced attempts at ‘rational’ resolution that so many people attempt to apply in such circumstances.

As for why certain people seem incapable of understanding that discussion is not always or only about them, and that a description of a specific scenario might in fact solely be in use to illustrate a much broader and more general point, all I can suggest is that a certain song might apply. Oh well…]

Thanks Mr. G.

Three things.

1. Laugh at Trolls who set out to agitate and annoy. Why not put the unwanted comments within text star boundaries and thank them within the boundary? i.e ******** another unwanted entry – thank you *********

2. People should be grateful that I’ve not added my photo to this forum. That way the “pot calling the kettle black – I mean ugly” is only something they have to imagine.

3. “fairly typical of the kind of ‘not-insults’ that do help to reduce anti-client risks in the workplace” I concur – you and I have frustrated / annoyed each other all too often but I have significant respect for the outreach approach and continuing successful efforts in the arena of broadening architecture around business.

…and thanks again, Peter – much appreciated!

That Snowden approach sounds like ad-hominem in multiple shades – without knowing too much about why, I view all such personal attacks (vs countering of arguments) as bullying – behind which is insecurity and an attempt to establish the rule of the more ruthless (also the source of most of the despair in this world).