Metaframeworks in practice, Part 1: Extended-Zachman

What ontology-frameworks do we need, to make sense of the enterprise-architecture of a logistics-business?

This is the first of five worked-examples of metaframeworks in practice – on how to hack and ‘smoosh-together’ existing frameworks to create appropriate tools to help people make sense of a specific business-context:

- Part 1 [this post]: Zachman plus tetradian -> extended-Zachman

- Part 2: TOGAF plus PDCA plus US-Army AAR -> iterative-TOGAF

- Part 3: Group Dynamics plus Chinese wu xing plus VPEC-T -> core Five Elements

- Part 4: Jung plus swamp-metaphor plus systems-practice plus Kurtz/Cynefin plus OODA plus many-others -> context-space mapping -> SCAN

- Part 5: Business Model Canvas plus Viable System Model plus extended-Zachman plus many-others -> Enterprise Canvas; plus Five Element plus Market Cycle -> Enterprise-Canvas dynamics

In accordance with the process outlined in the ‘Metaframeworks in practice‘ overview-post, each of these worked-examples starts from a selected base-framework – in this case, the Zachman framework for information-systems architecture – and builds outward from there, to support the specified business-need.

Extended-Zachman framework

Business-need

During the mid-2000s we were working on business-transformation and enterprise-architecture for Australia Post, the national mail-provider for Australia. We needed an ontology-framework that could provide an overall categorisation-schema and primitives-structure for content-mapping across the whole of our business-context.

The obvious choice for that need was the Zachman framework. However, one of our core architectural principles was that “any process could be implemented by any appropriate combination of people, machines and IT” – and at the time, the examples shown for each primitive-type in the Zachman framework related solely to data and/or IT.

If we were to use Zachman, we would need to extend it to cover the full scope of our work: not just data and IT, but people, machines, physical ‘things’ such as letters and parcels, and preferably to link to business-purpose as well.

Metaframework process

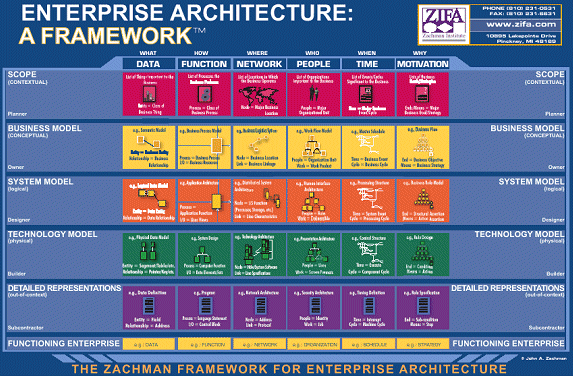

Start with Zachman (the version current at the time):

Select our existing mapping for the architectural-principle “any process could be implemented by any appropriate combination of people, machines and IT”:

Overlay and compare the two frames, looking for mismatch and incompletion – in other words, where one frame does not align with the other.

The overall ontology of Zachman is a good fit for our needs for IT and data, but does not seem to provide any coverage for people, non-IT machines, or physical ‘things’. It seems like there is an entire dimension missing from the framework, where the existing IT-specific view would be replicated (recursion) for these other types of items.

From my own ‘toolkit’, select a framework I’d developed some years previously, called the ‘tetradian’ because it’s formed of four dimensions in a kind of radial relationship:

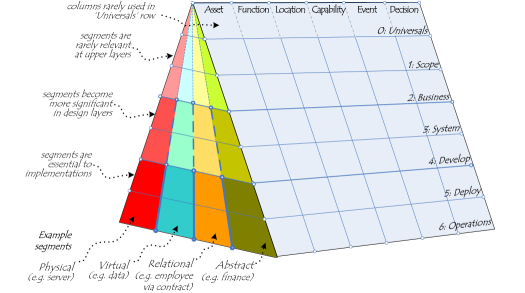

Overlay this tetradian on the Zachman frame, with each of the tetradian axes as a parallel plane in a third dimension relative to the original two-dimension frame. For an initial fit, the existing IT-oriented content in Zachman represents the ‘Virtual’ tetradian-dimension; the other tetradian-dimensions – physical (‘thing’-related), relational (people-related) and aspirational (purpose-related) – are placed on separate parallel planes or ‘segments’.

Review for conceptual balance and/or mismatch.

The first point arising is that the planes or ‘segments’ are not actually parallel. In the higher rows of the Zachman frame, the segments should not be relevant: for example, we want to know that a particular type of service would need to exist, but with no real concern at that level as to how that service would be implemented. In the mid-range rows, we want to be able to try out and compare different options for implementations, hence the segments both do and do not matter. In lower rows, the exact implementation – and the respective mix of segments – is fundamental. The result is that the relationships between the segments are less like parallel planes and more like an expanding curve or, more simply, a wedge, expanding outward from the top:

Second, the ‘Aspirational’ tetradian-dimension didn’t quite fit with our needs for that project, so we substituted an alternate dimension labelled ‘Abstract’, for money, finance etc. [In a later revision, this was largely dropped, and the ‘Aspirational’ dimension reinstated, because money and the like are more accurately a composite of ‘Virtual’ (data) and ‘Aspirational’ (intent plus brand). In the current version, the ‘Abstract’ plane does still exist, but is used solely as a placeholder for the special-case of time as a non-asset class of Location.]

Third, since the Zachman frame in essence described a change-process, from most-abstract to most-concrete, we found that we needed two extra rows:

- row-0 (new): represents core items that should never change, such as whole-enterprise vision

- row-6 (expansion/re-purpose of Zachman ‘Functioning Enterprise’ row): represents unchangeable past, such as in records of change or action

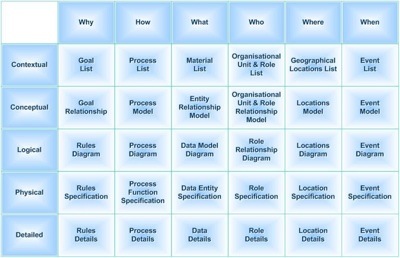

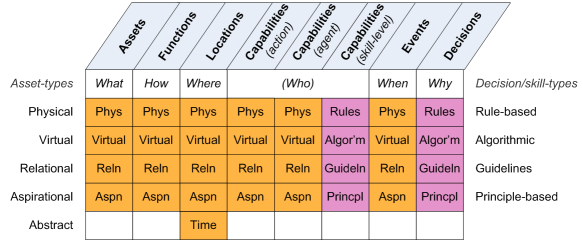

Fourth, we became increasing uncomfortable about the Zachman column-labels, and what they were actually supposed to represent. The original ‘What, How, Where’ etc made sense at the top rows, but become oddly misleading (balance: reciprocation and/or resonance) as we worked down towards descriptions of real-world implementation. Also the original ‘Who’ column clashed (mismatch) with the implicit ‘Who’ of the tetradian ‘Relational’ dimension. We eventually decided that the original ‘Who’ made sense only when the overall context was IT-specific: for anything else, it created huge inconsistencies across the ontology. What was needed instead was a more consistent description of capability as distinct from function in the ‘How’ column: these are often merged together for machines and IT-systems, but must be viewed as separate for human/’manual’ systems. For these and various other related reasons, we reworked the column-labels as follows:

- Asset (‘What’): physical things, data, person-to-person relations, person-to-abstract relations (e.g. brand, business-purpose)

- Function (‘How‘): functions to act on physical things, data, person-to-person or person-to-abstract

- Location (‘Where‘): locations and location-schemas in physical, virtual, relational or aspirational-space, plus locations within time

- Capability (‘Who‘): ability to act on physical things etc, plus agent in physical etc form, plus skill-level for decision-making

- Event (‘When‘): identifiable event in physical, virtual, relational, aspiurational etc form

- Decision (‘Why‘): decision or reason at specific skill-level, loosely cross-mapped to physical (rule), virtual (algorithm), relational (guideline/pattern) and aspirational (principle)

See the ‘Rethinking Zachman’ posts here (such as ‘Rethinking Zachman – a summary‘) for more detail on the reasoning behind that rework.

Download the two-page framework reference-sheet for the full version of the extended-Zachman framework used in my later book Bridging the Silos.

Originator-relations

Other than the tetradian model, which had been from my own previous work, all of the materials used for this metaframework exercise had either been the company’s own (the people/machine/IT cross-map) or relatively public-domain (Zachman), and at the time it was only for internal use within the organisation. The ‘unhappy originator’ risk therefore didn’t really apply.

Some years later, when I started to use the extended-frame in more generic form, I did need to take more account of that risk. When I finally met up with John Zachman at a conference, we discussed it at some depth, and happily disagreed: the only thing that really does need to be said about Zachman himself is that he’s always, and unfailingly, one of the nicest people I’ve ever met! 🙂

The ‘official’ Zachman frame has itself been updated at least twice since we did that work at Australia Post. Here’s the current version:

The ‘What’ column is still somewhat IT-centric, but otherwise it’s much more generic or broad-scope than it used to be. There are still serious gaps and inconsistencies – for example, ‘Geographical Locations’ appearing only at the Contextual level – and the ‘Who’ column remains largely unchanged, but the ‘When’ column is, in effect, an ‘Events’ column in everything but name.

Applications

The fundamental principle behind Zachman is that entities should be described in terms of ‘primitives’ (individual cells in the frame), but in real-world terms – and especially in lower rows – will actually appear as composites. Primitives enable re-architecting; composites are the outcome of real-world design and implementation. The same general principle also applies across the segment-planes (tetradian-dimensions) in the extended-Zachman.

We used this extended frame extensively as a guide in our architecture-work for Australia Post. Since then, I’ve always held it as a core part of my own enterprise-architecture framework-‘toolkit’.

I’ve also re-used it in somewhat different form in the later work on Enterprise Canvas, where the service-orientation of Enterprise Canvas modelling means that we can split the extended-Zachman frame into two parts. First, the vertical-axis (the Zachman-like rows), because each Canvas representation of a service in effect sits on a single row within the frame:

And since a service-representation sits at a single row, we can describe the service-content in terms of the extended-Zachman columns plus segments:

Using these two mappings, we can describe the role and content of any service of any type at any level of abstraction, anywhere within the enterprise.

Lessons-learned

Probably the most important lesson-learned here was to be wary of implicit IT-centrism in enterprise-architecture models and frameworks. It’s possible to get away with IT-centrism in information-centric industries such as finance, insurance, banking and tax, but it simply does not work in other type of industry. This is a problem that has arisen again and again throughout just about all of my work with metaframeworks in enterprise-architecture and the like.

—

Next worked-example: an iterative version of TOGAF, for broad-scope enterprise-architecture.

In the meantime, any comments or questions so far? Over to you, as usual.

Leave a Reply