What is a value-proposition?

‘Value-proposition’ is a term much-bandied-about in business-models and the like. Yet what exactly is it?

A tweet by Alex Osterwalder pointed me to an article by Steve Blank on ‘How to build a billion-dollar startup‘, which included this brief section on the role of the product or service:

Is It a Problem or a Need?

I’ve now come to believe that the value proposition in a business model (value proposition is the fancy name for your product or service) fits into either one of two categories:

— It solves a problem and gets a job done for a consumer or a company (accounting software, elevators, air-conditioning, electricity, tablet computers, electric toothbrushes, airplanes, email software, etc. )

— Or it fulfills a fundamental human social need (friendship, dating, sex, entertainment, art, communication, blogs, confession, networking, gambling, religion, etc.)

All fair enough: useful advice indeed. But wait a moment, what was that throwaway comment there?

…the value proposition in a business model (value proposition is the fancy name for your product or service)…

No, no, no! Fundamentally, completely, absolutely wrong! That view of ‘value-proposition’ is exactly what not to do!

Or rather, what Steve says above is how we’d usually frame it in classic push-marketing – where, to be blunt, the role of the supposed ‘value-proposition’ is often to hide the fact that the proposed product or service doesn’t have much real value…

In push-marketing, we start from the proposition, and then look for the value. We start from the product or service – something that we know we can make or do, and therefore want to be able to sell. To make it supposedly-saleable, we hunt around for something that could be called a ‘value’, especially one that could differentiate this product or service from all those others that look just about exactly the same because they’re things that people know how to make or do. Hence the idea that the ‘value-proposition’ consists of terms such as cheaper, faster, better, new. At least, as seen ‘inside-out‘ from the organisation’s perspective to ‘the market’.

It’s called ‘push’ because we use the supposed-value to push our product or service at people. And it’s clear, simple, easy to understand, easily measurable, and all the rest, so we see it absolutely everywhere – but it doesn’t work well, for anyone. In many cases, all it really manages to do is create ‘a race to the bottom’, where no-one wins. Oops…

By contrast, in pull-marketing, we start from the value, and then look for the proposition. (Value first, then proposition: that’s why it’s correctly called a ‘value-proposition’.) For example, as Steve Blank does explain well in the second half of that quote above, two key categories of value are problem and perceived-need. Chris Potts summarised it nicely in the following tweet:

- Value-proposition: listen to music wherever you want, with no discs, tapes etc. Product: (eg) iPod.

(To be pedantic, Chris’ ‘value-proposition’ there is more the ‘problem’ or ‘need’, the driver that links between value and value-proposition: we’ll come back to that in a moment.)

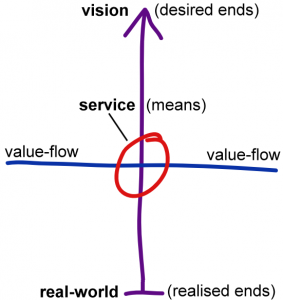

It’s called ‘pull’ because we use the connection to a broader meaning of value to pull people into mutual conversation with us, and thence from that conversation identify an appropriate product or service for their problem or need. It’s not as simple as ‘push’, partly because what we need to deliver may vary quite a lot from one person to another, partly because we need the empathy to work with an ‘outside-in’ perspective rather than from a literally self-centred ‘inside-out’ view, and partly because we have to juggle two different meanings of ‘value’ – the ‘vertical’ connection to vision and values, which creates the pull, and the ‘horizontal’ flow of value that satisfies the need. Yet when it’s done well, the power of pull provides for everyone’s needs – and everyone wins.

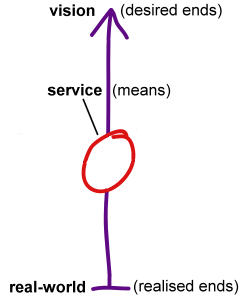

Let’s use Enterprise Canvas to look at this. First, to simplify things, we assert that ‘everything is a service’ – a product is thus a kind of ‘proto-service’, a means through which to deliver a self-service. In the most basic view in Enterprise Canvas, a service is a means to an end that sits somewhere on a vertical axis between desired-ends – what we want the service to deliver, or help to deliver – and realised-ends – what the service can or has actually delivered:

We’d typically apply a ‘Five Whys’ to identify the overall vision and concomitant values for this service. To me, the vision has three distinct components that are shared by everyone in the effective shared-enterprise:

- the what or with-what – something that identifies for the content or focus for this enterprise

- the how – some kind of action on that content or focus

- the why – a qualifier that validates and bridges between content and action

Various values fall out of the vision – and they provide the reason for people to connect with each other across the enterprise, the value that forms the start-point for the value-proposition.

To use the TED example, “ideas worth spreading”, the whole point is that these are not just ideas that are being spread around, these are ideas that are worth spreading.

Or, to use Chris’ example above, the real driver is more like good music everywhere anywhere. Which then leads ‘downward’ (more towards the practical-detail of ‘how’ and ‘with-what’) to:

- music I can carry with me

- add a bit more detail: my own choice of music I can carry with me, without hassle

- expand on ‘without hassle’: preferably something small that I can easily carry anywhere and doesn’t need the clutter of discs or tapes

Which brings us to Chris’ specific ‘value-proposition request‘. To which an example-response – the proposition in the ‘value-proposition’ is, as Chris says, the iPod. Starting from the vision and the value, the service presents – proposes – an offer which would satisfy a need in relation to that value. That’s why we talk about ‘value-flow’, because it’s a flow or sequence of exchanges that in some way delivers something ‘of value’ for everyone in relation to that value. Hence, in visual form:

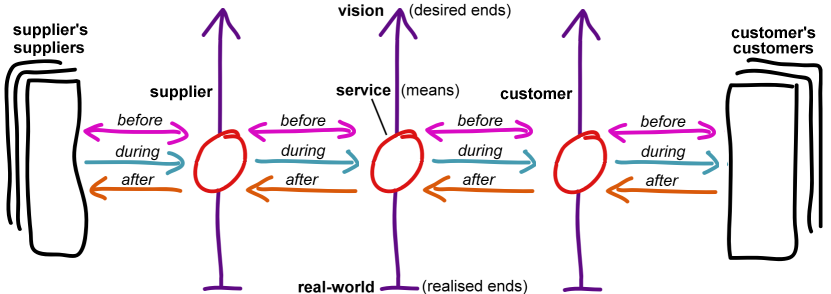

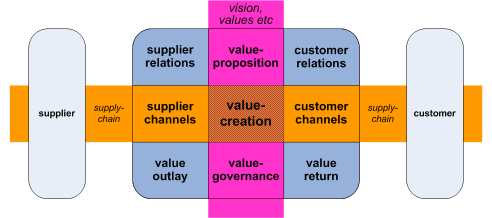

And if we expand this view outward, as a value-chain or value-web:

At each stage in the sequence of exchanges, the respective players establish the connection of shared-vision and values, and then explore the proposition that the service-provider offers, to satisfy a problem or perceived-need in relation to the vision and values. The connection of values provides the ‘pull’ towards the value-proposition. This happens in distinct stages:

- before transaction: establish the value-connection – the effective definition of what value ‘is’ in this context

- before transaction: explore the relevance of the value-proposition – how and to what extent, relative to those values, this product or service will satisfy the overall problem or perceived-need

- during transaction: deliver the product or service in accordance with the proposed delivered-value – such as specified in a service-level agreement – again, relative to those specified or implied shared-values

- after transaction: evaluate satisfaction in relation to the offer or ‘promise’, and ultimately in relation to those shared-values

- after transaction: resolve any required value-balance – such as via payment etc

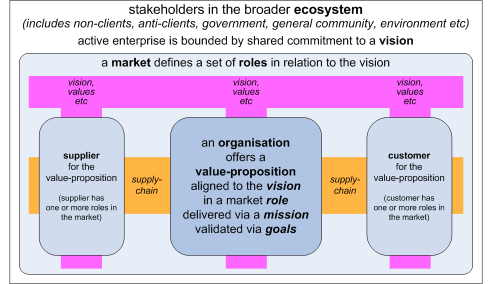

To summarise those overall relationships in a bit more detail:

The value-web isn’t solely about the horizontal supply-chain: that’s just the how and with-what of the transactional relationship. That’s the visible part of value, sure, yet it’s actually held together through a more vertical connection of why – the reason or purpose for the relationship between the players to exist. Value-proposition provides the link between why, how and with-what.

Incidentally, this is the key reason behind a perhaps-subtle yet important difference between Business Model Canvas – focussed on the core business-model – and Enterprise Canvas – designed more for whole-of-enterprise architecture.

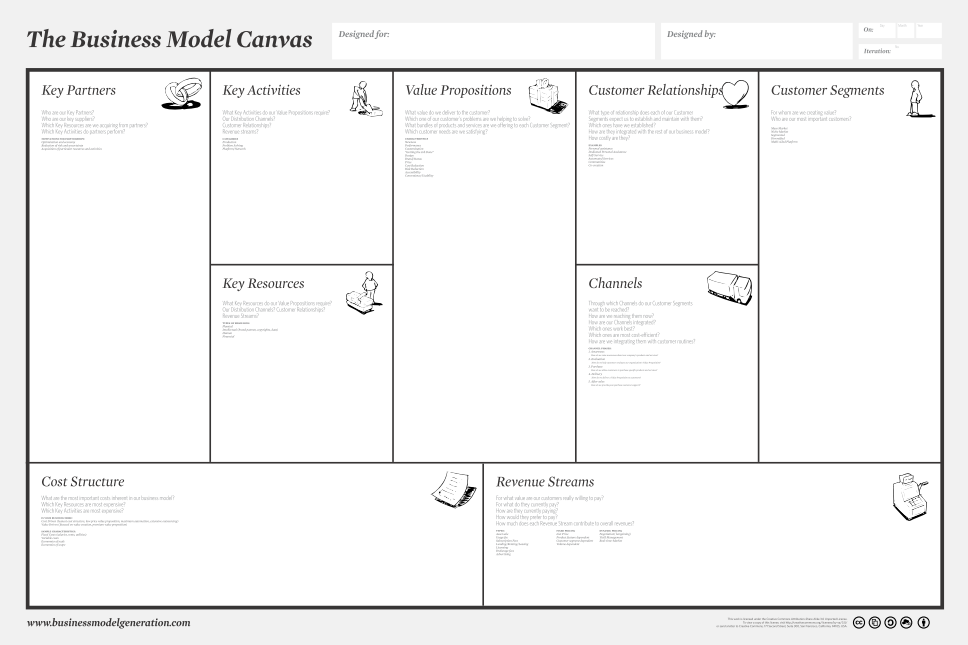

In Business Model Canvas, the Value Proposition cell provides the central spine for the whole business-model:

Yet it provides us with no means to distinguish between value (horizontal) and values (vertical), nor to distinguish between the value-metrics for a product or service, versus the product or service itself – they’re all conflated together into the one ‘value-proposition’. Which, in effect, forces us into Steve Blank’s assertion that “value proposition is the fancy name for your product or service” – and, in turn, all but traps us into a push-marketing model for products and services, which rarely works well.

In Enterprise Canvas, though, we draw explicit distinctions between those different concerns:

- value-proposition proposes value – it establishes the connection to (vertical) shared-values, as a shared story, and identifies the (horizontal) problem or need to be satisfied by the provider

- value-creation creates value – it delivers (horizontal) value against the identified and agreed problem or need – typically in the form of products and/or services – and in relation to the shared-values

- value-governance governs value – verifies that value has been delivered in accordance with the problem or need and the shared-values or story, to the satisfaction of all parties in that story

Together, these three cells form the central spine of business-model, much as with the single Value Proposition cell in Business Model Canvas. Yet whilst they’re strongly interdependent, and in some ways act as one, they deal with distinct and different aspects of the overall value-flow in the business-model, and in practice they’re often enacted by different people or entities, too. It also makes it much easier to understand how to design a ‘pull’-based business-model, rather than default back to the inherently-ineffective ‘push’. So overall, it’s definitely useful to be able to separate-out the different sub-themes in this way:

This three-way distinction also makes it simpler to understand the different interactions that happen – often with different parties – in the different stages of the value-flow. And since any given service in an enterprise is both a provider of some services, and also a consumer of other services, it does make more sense to lay this out in symmetrical form – another subtle-yet-important difference from Business Model Canvas:

If we turn this sideways-on, with the ‘inside’ spine on the left, and the ‘outward-facing’ elements on the right, we can then also describe the overall sequence and structure and drivers of the interactions and sub-flows that make up the overall story of the business-model:

Again, each of those central cells (or, in this diagram above, the left-hand cells) manages a different part of the business-model story:

- value-proposition guides and drives the why for the service’s activities

- value-creation presents the how and with-what of the service and its products, linked back to that why

- value-governance links and verifies the with-what, the how and the why, always striving to reduce the gap and tension between desired-ends and realised-ends

In short, value-proposition is not “the fancy name for your product or service”: yes, they’re closely related, but they do need to be understood as separate and distinct.

And if you do allow them to blur together, the business-consequences are often not good at all: You Have Been Warned? 🙂

Tom: This is excellent. I was especially taken with your use of “concerns” when referencing the three value… well, concerns. I just got done reviewing The Decision Model and found their application of “separation of concerns” to be puzzling. Anyway, quite awhile ago you discussed internal visions as opposed to external visions. Would you please elaborate from that discussion onto the vision discussion here?

Thanks, Myron. (As an aside, ‘separation of concerns’ is to me largely about capabilities and skillsets: we partition the work according to the competence and capability, both in terms of skill-level and in terms of scope of knowledge and ability-to-act. I’d hasten to add that that’s just an aside, though, and needs a lot more explanation!)

On internal vision versus external vision, in essence it’s that distinction between perspectives: inside-in, inside-out, outside-in, outside-out.

(A quick reminder that a goal or objective doesn’t work as a vision in this sense: if it’s time-limited or achievable, it’s not a ‘vision’ in the sense I’m using it here. Also, since ‘vision’ can have a specific meaning in a Christian context, you might be more comfortable with a term such as ‘promise’ or ‘guiding-star’ as an alternative: in essence, it’s something that indicates a direction or frame-of-reference but is never actually ‘achieved’.)

An inside-in vision centres around value-concerns such as efficiency and reliability: it’s almost entirely about how our own systems are working, regardless of anyone else. Engineers and line-managers often focus very strongly on this form of vision. (To give a military example, think of a junior officer who obsesses about the smartness and obedience of his unit, without any reference to whether they are competent as soldiers out in the field.) This type of vision is extremely important operationally, but needs to be anchored in context with the real ‘outside’ world.

An inside-out vision is self-centric in relation to others: “we are going to be the best of…!” and suchlike. In many cases – for example, very common in scrambled concepts of business-‘strategy’ – it’s so much about the self that it leaves no room for anyone else: which is also why it often doesn’t work well. 😐 An inside-out vision must be linked to a matching outside-in vision if it is to succeed as a ‘guiding star’.

An outside-in vision is typically an expectation or hope of quality-of-service: “can this service give me what I need, or help me with what I need?” There’s often an associated goal (i.e. explicit delivery of service fit for the purpose), yet it’s also a vision in the sense that the service-delivery could always be done better – and hence not ‘achievable’ in the same sense as a goal. When we model a customer-journey, or quality-of-service from a customer-perspective, it’s this form of vision that we need to understand.

An outside-out vision describes the aim for a ‘desired-world’ – such as via that three-part what / how / why that I summarised in the post above. This provides the ultimate “because…” or end-point for the trail of ‘why’ for each of the other forms of vision. Unlike the other forms of vision, there is no further “because” attached to this: it’s just an arbitrary choice or desire, a defining and definite “Because.” in its own right, the driver for ‘enterprise’ and so on. (Christians and suchlike might well ascribe this “Because.” to God or to ‘the will of God’ or some such, and assert that it’s not arbitrary at all, yet the overall principle is the same either way, I think?)

The outside-out vision provides the anchor-point for the trails of value that must permeate through the whole shared-enterprise. The outside-out vision and its values provide the reason why outside-in and inside-out should want to connect; it also provides the anchoring context for a useful inside-in vision. (Where inside-in focusses more on fitness side of ‘fitness-for-purpose’, outside-out provides the purpose behind ‘fitness-for-purpose’.)

Okay, yeah, I’ve rambled somewhat again, but I hope that provides a bit more clarity on those distinctions – and thence where ‘value-proposition’ comes from?

Sorry, this may be a bit off the subject here but is there somewhere a good model for the process of designing services or value propositions from idea to production.

The word service design seems to have two (at least) rather different meanings. The design thinkers talk mainly about customer experience journeys and ITIL is more about fulfilling requirements by the waterfall method and designing for the production of the service.

Many thanks, Aale – and no, I don’t think it’s “off the subject”, I think you’re on to something important there.

To some extent I’d hope my reply to Myron may answer some of this: the design-thinkers are working with an ‘outside-in’ vision of service, whereas your description of ITIL suggests a focus more on an ‘inside-in’ vision of service. The ‘outside-out’ vision provides the context within which to link them together.

I was going to suggest the book “This Is Service Design Thinking“ but realised on re-skimming it just now that it fits primarily in the ‘design-thinker’ space, without much direct linkage to an ITIL-type view of services. Another book that might do somewhat better is Milan Guenther’s “Intersection“: it doesn’t describe service-design as such, but summarises the roles and relationships of each of the players in the service-design space.

Hope this helps somewhat?

Aale, Tom,

“This is Service Design Thinking” is certainly in the design thinking space but also has some practical advice. Milan Guenther’s “Intersection” might be useful in this context, but it’s quite bit of work to get through.

I’d actually recommend at the “official” ITIL v3 literature: when I looked at it a while back, I was very impressed how much of the generic (ie non-IT) service management space was covered, especially in the Service Strategy volume…lot’s of current thinking on service marketing, design and operations.

Best regards,

Oliver

I think the idea that a value proposition addresses a problem or need completely overlooks one of the most important kinds of value proposition — those that address an opportunity. There is of course the well-worn cliche about turning a problem into an opportunity, but let’s face it, if you call something a problem, your first instinct is to fix it, not take advantage of it. Similarly, most innovative opportunities do not manifest themselves as an extant need — again, we have the cliche that the best products address a need that the market didn’t know it had. “Problem, need, opportunity” has become for me one of those tripartite mantras like “why, what, how” or “people, process, technology” — the parts become inseparable, so when I think of one I automatically think of the others.

len.

Len – yes, good points, especially re opportunity and “the best products address a need that the market didn’t know it had”. Yet I don’t think it’s fair to assign that to Steve Blank himself: if you read the context of his post, I think it’s clear that it’s first and foremost about (business)-opportunity, and thence to looking for opportunity amongst themes such as problem or need.

I’d certainly agree that it’s much broader than problem or need, though – for example, ‘problem or need’ tends to be reactive, whereas ‘opportunity’ is often more proactive. A lot more to explore there, I think? 🙂

Tom concludes with:

“In short, value-proposition is not “the fancy name for your product or service”: yes, they’re closely related, but they do need to be understood as separate and distinct.

And if you do allow them to blur together, the business-consequences are often not good at all: You Have Been Warned?”

Exactly, because doing so is a perfect example of conflation — mistakenly identifying “value proposition” with “product or service”.

len.

@Len: “doing so is a perfect example of conflation” – yes, exactly.

Tom,

I’d like to add a reference to Nick Malik’s seminal blog post where he analyses the data model of the Business Model Canvas. It clearly shows how value proposition and products or services are different things. It is one of the best articles I’ve ever read on this topic.

http://blogs.msdn.com/b/nickmalik/archive/2012/08/22/the-ea-metamodel-behind-the-business-model-generation.aspx

Alex – yep, very good (and important) cross-reference: thanks for bring that in here.