Four principles for a sane society: an addendum

What architectures do we need for a society and economics that’d be viable and sustainable over the longer term? And how do we scale that down to the the everyday work we do at present in enterprise-architectures and the like?

In the previous series I outlined four principles that seem to me to be essential for this:

- there are no rules (there are only guidelines)

- there are no rights (there are only responsibilities)

- money doesn’t matter (but values do)

- adaptability is everything (but don’t abandon the values)

Yeah, I know: not exactly mainstream… and much of it politically-unacceptable to both right and left, too, which brings up some interesting challenges… Oh well.

So I perhaps need to reiterate that this isn’t something I’ve casually thrown together over a weekend or two: there’s actually several decades of study, research, analysis and reflection that’s gone into this, in particular on identifying fundamental requirements and constraints, and on identifying practical approaches and techniques that can be used over the respective timeframes. Every one of the problems I described in those posts is real, solid, and almost certainly inescapable, in terms of where the dominant global culture is currently headed; and every one of those four principles and their concomitant strategies represents a big-picture overview of what we must do in order to avoid the otherwise-inevitable denouement of the respective problems.

None of it is trivial – seriously.

At present, as a professional futurist, I literally do not see any other alternative – and yes, I have looked into it with a lot more depth and care than most people seem to do. (Hence, for example, why I say that no ‘alternative currency’ will solve the current global crisis with fiat-currencies, and that the only future of money is that it has no future – that’s not wishful-thinking, folks, it’s a key constraint on human survival in the longer-term.)

Yet as soon as people get over their first ‘you cannot be serious!‘ shock at this, and realise that, yes, I am serious, there seem to be two reflex responses: the ‘kumbaya’ dismissal, and the ‘it’s human nature’ excuse. The purpose of both of these objections seems to be to defend a literal ‘ignore-ance’ – which is a bit of a worry… And since, in the longer term, this is literally a matter of life and death – with the latter potentially on an almost unimaginable scale – it’s worthwhile to spend a bit of time on both of these two objections.

The ‘kumbaya’ dismissal views any questioning of the current possession-based economics as hopelessly idealistic. Richard West neatly summarised this attitude on Twitter in his happy retort:

RT @RiczWest: @tetradian You, Sir, are a Hippy! 🙂

Ric was joking, of course, but that is how a lot of people would prefer to interpret this: the stereotypic hippy with long hair and beard, huddled together with others around a campfire, smoking strange substances and singing ‘Kumbaya’ to the accompaniment of a badly-tuned guitar. “All peace an’ love, man” – hah! Let’s get back to the real world, shall we?

Nice idea, perhaps, but unfortunately I’m not much of a hippy, and I never was. Those campfires bring out the chilblains something rotten, y’know; my lungs aren’t up to smoking anything; my singing-voice is barely one step removed from a donkey’s; and I don’t even know how to play a guitar. Sorry. (Okay, I do have a beard these days, but that’s mainly to hide the fact that I’m all but bald: “my hair hasn’t fallen out, it’s just slipped down a bit…” 🙁 🙂 ) Fact is that I’m just a grumpy old backroom-boffin, and I probably always have been: the only difference is that I’ve now kind of grown into the supposed ‘proper age’ for the role. And it’s that boring old backroom-boffin that’s talking here, the futurist, the enterprise-architect – not the non-existent hippy in the tie-dyed suit. So this isn’t some kind of flittery-floatery acid-dream, it’s all depth-analysis and, much, much more, all of it just about as deep as it can go – and yes, it is indeed dead-serious. Literally. Not wise to be quite so quick to dismiss it, perhaps?

So let’s go through this once again:

— Personal possession and ‘property-rights’ are probably the foundation-stones for many cultures and for the current global-economy.

— A possession-based economy does tend to give better results for individuals in the short-term. (Which is why it’s such a foundation-stone of the global-economy.)

— However, any detailed study of possession-based economics would illustrate that it achieves its ‘better short-term results’ by creating externalities – in other words, and often in an all too literal sense, by stealing from (dispossessing and/or expropriating) others in the present and/or elsewhen. (A simple example: collectively we are blasting our way each year through something like 100,000 years’-worth of fossil-energy, which will therefore be unavailable to others in the future.)

— A possession-based economy seems viable in the short-term solely because it offloads most of its costs elsewhere and/or elsewhen. When whole-of-system costing is properly assessed, it becomes clear that there is no way to make a possession-based economy sustainable, especially in the longer-term.

— The only way to make a possession-based economy seem sustainable is to run it as a pyramid-game – hence the global-economy’s obsession with ‘growth’.

— The blunt reality is that it is impossible to have infinite growth on a finite planet. As with all pyramid-games, once the game runs out of room to expand, its only possible option is to cannibalise itself into oblivion. Many of the global indicators suggest that we are already well into that phase of the game.

— A ‘rights’-based model of property is inherently dysfunctional, as per all notions of ‘rights’. (All rights may be – and often are – ‘gamed’ into a paediarchy: ‘rule by, for and on behalf of the childish’.)

— As it reaches further and further into its self-cannibalisation phase, a global economy based on ‘property-rights’ will and must inevitably implode into increasingly-dysfunctional and decreasingly-viable states: a steep decline into ‘resource-wars’ or into slave-cultures dominated by narcissistic sociopaths with delusions of ‘entitlement’ above all others are just some of the more probable scenarios already starting to be evidenced in the present-day.

— Purported ‘property-rights’ are an abstract and arbitrary overlay on the actual mechanisms that enable economic interaction, namely interlocking mutual responsibilities.

— In the longer-term, the only viable option that we have is to reject the entirety of the ‘possession’ overlay, and rebuild the economics around the actual mechanisms of mutual-responsibility.

Or, in visual form:

The point that needs to be hammered home is that any instance of purported ‘possession’ or ‘property-rights’ – in fact any form of purported ‘rights’ – will and must automatically cause a fall-back into the same non-viable mess, or some other (probably worse) variant of that mess.

No matter how much we might wish otherwise, there is no way of getting around this fact: there is no way to make a possession-based economy sustainable. And the longer we avoid facing that fact, the worse the mess becomes, and the worse our collective chances of long-term survival also become. It really is as fundamental as that.

Hence talking about an end to possession-based economics is not ‘kumbaya idealism’ at all: it’s almost certainly the only viable strategy for long-term survival that currently exists.

In short, it’s the most realistic and pragmatic view of economic reality: the ‘woolly-headed idealists’ are the ones who think that possession can somehow still be made to work. 🙂

The catch, of course, is going to be in getting this shift to happen, in the (relatively) short time in which we must somehow make it work. Ouch…

Which brings us to the ‘it’s human nature’ excuse – the idea that possessiveness and suchlike are ‘just human nature’, and therefore there’s no possible alternative to a possession-based economy.

All I can say to that is that it’s bullshit: a really shallow excuse, and ultimately a suicidal one at that – but a form of suicide that threatens to take everyone else with it, which is not a good idea from anyone’s perspective…

The reason why it’s bullshit is that it’s based on nothing more than intellectual-laziness – a very thin and inadequate understanding of what ‘human nature’ really is.

Selfishness, self-centredness and possessiveness are indeed ‘human nature’ – for a two-year-old. It’s an entirely natural outcome or side-effect of a transient developmental stage. Unlike the one-year-old, the two-year-old does have a grasp of the distinction between ‘self’ and ‘other’, but doesn’t have much grasp of self in relation to other: it still sees itself as the sole centre of the world, the point around which everything else revolves. The typical two-year-old sees everything ‘other’ as objects to be used according to whim, or as subjects that exist only as semi-autonomous extensions of self and that ‘should’ automatically know, act upon and serve the child’s whim. (Stereotypically, the object-based view is ‘male’, the subject-based view is ‘female’, but in reality gender plays only a small part in this.)

For a while, as it passes through this phase, a normal two-year-old will hold an unshakable certainty that it is the centre of everyone else’s world, that it is entitled to priority over all others – and be very vocal, demanding and even aggressive in asserting those ‘rights’ over others, too. (The resultant temper-tantrums and the like are why this stage is colloquially known as ‘the terrible twos’…)

Yet this is – or should be – a transient phase: in most cultures, a normal four- or six-year-old will have a fairly solid grasp of sharing and of mutual responsibilities in a social context. In functional cultures, even an eight-year-old would begin to have a fair grasp of systems-thinking, awareness of the interdependence of everything on everything else. Clinging on to possessiveness and the like, beyond about three or four years of age, is a developmental disability, or literally a social pathology – hence the term ‘sociopath’.

In a paediarchy, though, possessiveness is regarded as ‘normal’, and is actively rewarded, whilst a more natural sharing (‘natural’ in terms of normal child-development) is often denigrated, deprecated, or openly mocked: certainly there will be active disincentives to share. This can be seen, for example, in the way that Ayn Rand – the high-priestess of a popular cult of self-importance and self-centredness – derided altruism as ‘evil’. At the least, in my own first-hand experience of US culture, altruism is still often viewed there as something very odd, a strange social-pathology giving rise to a compulsion to share with others without thought of immediate personal gain. In most other cultures, however, altruism is correctly understood as normal whole-of-systems-aware behaviour – and a real necessity for the society’s survival…

Let’s be utterly blunt about this: paediarchy is fundamentally sociopathic. Our entire ‘normal’ possession-based economics is paediarchy writ large, and hence is fundamentally sociopathic, actively rewarding childish self-centredness and sociopathic behaviour, and often actively penalising more-adult responsible behaviour. The whole foundation of our current economics is pathological: at least in terms of normal child-development, there is no other way to put it.

Hence, we might suggest, it might be wise to develop an economy that’s not based on a child-development pathology…

So how the heck do we do that?

Where I’d suggest we’d best begin is to look much more closely at habits and behaviours – both individual and collective – and the social and other architectures that support them. And to start that exploration, we can note that there are very strong parallels between the layering of structures in the brain (‘lizard-brain’ versus cortex etc), the developmental processes of learning how to use those layered structures, and the development of integration of sensemaking, decision-making and action, leading to a literal ‘response-ability’ – the ability to choose appropriate responses in a given context. In short, how we learn to choose and have some degree of direction over what happens to and with and for us in the real-world.

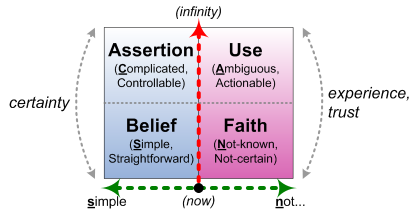

Probably the simplest to describe this (and be warned that yes, this is hugely over-simplified, although essentially valid) is to use the decision-making variant of the SCAN frame:

For most work with SCAN I’d typically focus more on the horizontal axis, the ‘order’/’unorder’ split either side of the vertical red-line; but for here I want to emphasise the vertical dimension, because in effect that dotted-line boundary represents the crucial distinction between the emotion-driven limbic-system and ‘lizard-brain’ below the line, and the ‘rational’ cortex and neocortex above.

Again, I’m massively over-simplifying here, but in essence the ‘rational’ systems work mainly on processing and reflecting on the senses. Yet crucially, all of that processing takes time – and in effect, it takes place at some distance from the action. When we’re at the point of action, the ‘lizard-brain’ and suchlike are what actually run the show, because they can respond ‘in the moment’ – and it’s the ‘lizard-brain’ and suchlike that in effect determine so-called ‘human nature’.

That dotted-line transition in SCAN represents that same transition between guidance for reflection versus guidance for action. Which in turn is very similar to the transition between Newtonian-physics versus quantum-physics: Newtonian-physics looks smooth and predictable and certain, but underneath it all of it is actually driven by sharp-edged and often somewhat-unpredictable quantum-transitions.

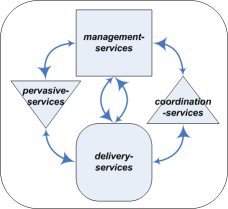

But note that the ‘boundary’ is porous: it’s not one-or-the-other – one ‘over‘ the other – but much more like a cooperative partnership, which side focussing on its own roles and responsibilities, but committed together to the best working of the whole-as-whole. One useful metaphor here is the partnership of rally-driver and rally-navigator – respectively the lizard-brain driving the action, and the cortex providing big-picture awareness and reflection. Likewise we can see the same partnership of distinct roles and responsibilities in the underlying structure of Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model:

Which, for a service-oriented view of the respective architecture, I simplified to:

Which I then reworked into the upper part of the Enterprise Canvas model:

The ‘lizard-brain’ and suchlike (the human equivalent of the ‘control-functions’ for the VSM’s ‘system-1’ sub-units) drive the service itself – the actual delivery of the various services of the human body and its actions, and the real-time choices for those actions. The cortex and suchlike (equivalents of the VSM system-3, -4 and -5 ‘management-services’ or ‘direction-services’, system-3* ‘pervasive-‘ or ‘validation-services’, and system-2 ‘coordination-services’) drive the other longer-term coordination, reflection guidance and review. They’re not separate from each other, and it’s not one-way (as in Taylorism) but an interaction between ‘head’ and ‘heart’ (to mix metaphors somewhat).

In effect, ‘human nature’ is a palette of options that are sort-of (but only ‘sort-of’) hardwired into the human systems. But whilst the palette is fixed (sort-of), the use of that of that palette is not. The trick here is that the ‘lizard-brain’ et al are creatures of habit, in terms of the ways they use that palette of options – and, given the right conditions, those habits can be changed. The change can sometimes take place in an instant, but more usually it’s via a process of gentle nudges and reminders just ahead of the moment of action – just enough to tweak things a bit, not enough to disrupt the action itself. Overall, it’s similar to the ‘counter-entropy‘ trick that living-entities leverage to create their niche for life in a mechanical universe: it’s a trick, and it works, but it depends an awful lot on the timing…

So although we can’t change ‘human nature’ as such, we can choose to emphasise or de-emphasise different themes within it, and (re)build new habits around those changed emphases – which, in practice, does come to much the same thing as changing human-nature.

Which is how and why different cultures are different: it’s because they emphasise and de-emphasise different aspects of ‘human nature’.

So yes, possessiveness is ‘human nature’ – for a two-year-old child. But we also know that it’s a habit of behaviour that’s not viable in the longer-term at a cultural level – especially in a resource-constrained, rapidly-changing context. Possessiveness leads to an inefficient and ineffective use of shared resources: it really is as simple as that. So in most social environments – such as in those we’d call ‘families’ – we would aim to de-emphasise those possessive behaviours, and instead emphasise other aspects of ‘human nature’ such as sharing, altruism, notions of fairness and suchlike – which is otherwise known as ‘growing up’ in a social sense. Someone has to grow up and do the adult work, the adult thinking, otherwise the society won’t be able to survive.

In a paediarchy, though, the now-dysfunctional childish habits are retained and reinforced, through the usual social mechanisms such as praise and reward. The adult/child relationship is inverted: the childish are deemed the ‘masters’, the ‘owners’, the ‘entitled ones’, whilst the adults are the ‘servants’ who seemingly exist only to do the ‘master’s bidding – which is exactly how a two-year-old sees the world in relation to itself. Yet when childishness is actively rewarded, and responsibility is mocked, derided, penalised, punished, who would want to be an adult? Oops…

We now have a global culture built on ‘property-rights’, possessiveness, and systematic evasion of long-term responsibility. It gives successful-seeming results for some in the short-term because it steals from elsewhere and elsewhen, and ignores anything in the longer-term – just like a two-year-old child does.

To be blunt, what we now have as ‘the economy’, worldwide, is a culture that bases itself on childish possessiveness, which in turn is the outcome of a collective, culture-wide choice to not grow up. Which is not exactly a wise choice: as a mother would no doubt say to her children, “I know it’s fun now, but it’ll only end in tears!”

And to also be blunt, that culture – our culture – is rapidly running out of places and times to steal from, and the distant-seeming long-term is rapidly becoming right-here-right-now: so we have a very real problem that will not go away and cannot be ignored any longer.

But the point here is that that possessive paediarchy is a choice, and we can choose otherwise: and at this stage it’s getting kinda urgent to we do choose otherwise…

So how do we choose otherwise? The short answer is: start looking at things that do work in the longer-term; learn from them; and then face the architectural challenges of adapting them to a broader context at a global scale. For example:

— Many indigenous cultures have been stable for very long periods of time: up to 60,000 in the case of Australian aboriginal culture. There’s a lot we can learn from those cultures, and groups like the Pachamama Alliance also provide an active laboratory for adapting those experiences to the present-day. In a significant number of cases, they do show us how to integrate whole-of-system awareness into a social culture that is resilient and self-adapting over huge environmental, climatic and other changes. The catch is that so far most of this has worked only with relatively-small social groups, and often with relatively simple technologies: what we don’t yet know is how to apply it to much larger populations in modern cities, with all the added complexities of urban stress, urban living and urban supply-chains that are already stretched almost to breaking-point.

— In the work-environment, the inherent dysfunctionalities of the ‘top-down’ command-and-control management-model are now fairly well understood. (Sadly, the model itself is still widely promoted in business-schools and elsewhere as ‘a good idea’, even though it is manifestly a by-product of the self-aggrandising myths of an out-of-control paediarchy.) As a contrast, there is much that we can learn from other forms of management – from the long-established cooperative-movement, for example, or from employee-owned businesses, all the way up to large-scale industrial conglomerates such as Mondragon – and the ways in which these models can support greater resilience to the stresses of change. What we don’t know is how to introduce and support those alternative models within a legal and economic framework which, at present, has huge vested-interests against their existence: for example, by definition, employee-ownership disintermediates and renders redundant any ‘external-owner’ stock-exchange and the whole ‘money-mess’ that surrounds it.

— One of the all-too-common characteristics of childishness is a lack of thought, not just about others but also about consequences of actions, especially at a less-visible and less-direct systemic level. Likewise one of the characteristics of a paediarchy – and one of the means by which it maintains its control – is a cultural-wide suppression of systemic thought, instead insisting on rote-learning, repeating ‘received-truths’ whether or not they are still ‘true’ or relevant in the current context. This doesn’t work when most of the so-called ‘certainties’ cease to be certain at all: the real need here, to paraphrase Margaret Mead, is that children need to be taught not so much what to think, as how to think. Through long-proven methods such as HighScope, we do now know how to teach even three-year-olds that actions and inactions alike always have consequences, and that self-awareness and self-responsibility is the only way works well for everyone – and to teach all of this, effectively and quickly, at large scale, even in the most stressed of urban environments. What we don’t know is how to make this work in a context where, in effect, the children’s habits and behaviours will be more ‘adult’ than those of the nominal adults – possibly for at least two or three generations.

So yes, there are some real challenges there. Or, to be honest, they’re huge long-term challenges on a truly global scale – and it’ll need a huge amount of inventiveness, subtlety and just plain hard work for it to be put in place within the fast-narrowing time-window we have available in which to make it work. Scary indeed. But please, don’t let us hide from those challenges in the ‘it’s human nature’ excuse: it really is nothing more than a pathetic excuse for procrastination, and we simply don’t have the time to waste on that.

Time to get moving, folks: there’s a lot of architecture-work that needs to be done, all the way out to the really-big-picture level, to rebuild the viability of this shared-enterprise of our shared world.

Hi Tom,

There is some serious analysis and synthesis work in these posts. I don’t think you are a hippy – you are a revolutionary!

Personally, I’d rather have rights with responsibility, and the ability or at least potential for free people to continuously experiment (counter-entropy) in seeking a balanced society.

For the sake of argument I accept all the critiques of modern Western-style democracies, but I’d rather take them with all their blemishes and imperfections over any society that felt civil liberties where inconvenient from a central planning perspective.

Are we more ‘responsible’ if we subsume ourselves to a hive mind or just more subservient/dependent? How will decisions be made? What properties of this new organizational style will give us perfect insight and ensure optimal outcomes collectively, if not individually?

I appreciate that ancient cultures are easy to romanticize from a distance. I’m not convinced they represent perfect models either.

My concern is that ending individual liberties or “rights” in the name of saving humanity has been tried before. It has been the pretext of many a repressive totalitarian regimes that fell quite short of their “best intentions” while brutally repressing those that would dissent.

Does anyone believe that we’d all be better off if a special class of people – Enterprise/Social Architects or otherwise – should plan our existence and that could ever be fair/just or humane/ennobling. This is the fallacy of central planning – http://mises.org/daily/4221. Age old despotism cloaked in an intellectual conceit.

Yes, modern Western-style democracies are very flawed, Governments are too big, power too centralized and access by monied interests too opaque and corrupting – but the system never claimed to offer Utopia, the model itself was a reaction against any form of patronizing authoritarianism.

While I enjoy reading your work, I believe the proposed cure kills the patient more directly than the system it seeks to replace.

Respectfully,

Dave

Dave – ouch…

First, thanks very much for taking me seriously on this – at least enough to write a comment here! Many people would just write me off as a nutcase, or as the wrong kind of ‘revolutionary’ – and you didn’t, so I really appreciate that.

The rest of this is where it gets really tricky, because I don’t think you’ve yet fully grasped what I’m talking about: it goes a lot deeper than suggested in your concerns above. Remember that I’m not actually proposing anything, any manifesto, anything like that – and I’m very careful about that, too. All I have done – and I repeat, all I have done – is describe what doesn’t work, why and how it doesn’t work, and why we can’t continue to try to use them for the longer term (because doing so would inherently render the overall economy non-viable – which is not a good idea…).

I haven’t proposed any ‘solutions’ at all. (Read it again if you doubt me on this: the nearest you’ll see to ‘solutions’ are a few “for example,…” pieces, that are literally there for examples of how things might perhaps be put together, so that the discussion doesn’t sit entirely in the abstract.) What you might interpret as ‘solutions’ are some of the constraints – such as the very real constraint (arising directly from the analysis) that any form of possession will lead automatically to a non-viable architecture, and for that reason must be excluded from any proposed architecture-‘solution’.

What we’re actually after here – and I think we’d all agree on this? – is an architecture that is capable of coping with the scale of the changes that we’re facing over the next few decades. Remember that the changes we’re facing will almost certainly be on what is previous a literally-unimaginable scale: in particular, whether we like it or not, a transition from a (fundamentally-insane) infinite-growth economy to a (possible-viable, if we do it in time) dynamically-sustainable economy. In effect, that’s what Principle #4 was about: the ability to adapt continuously and appropriately to whatever changes come our way.

Principles #1, #2 and #3 identify specific constraints that are needed to make the outcome of Principle #4 possible.

Principle #1 is about rules: trying to build everything on fixed rules in a dynamically-changing context is clearly non-viable, so we have to look for what’s behind rules that does give us the same outcome. That’s where guidelines and principles come into the picture: they provide guidance within uncertainty. We can use rules as if they’re certain, as long as we’re careful to realise that they actually aren’t.

Principle #2 is about a specific type of rules called ‘rights’. Since they’re a kind of ‘rules’, they likewise must fall by the wayside, because they can’t cope with the kind of uncertainties that we’ll be dealing with. There isn’t a choice about that: it’s not that they don’t work well enough as yet and could perhaps be tweaked to make them work better, it’s that the fundamental idea itself is too flawed to work. (I explained in the post as to why and how that’s the case.) Fortunately, it doesn’t matter, because what we think of as ‘rights’ are actually implemented through a meshwork of interlocking mutual-responsibilities: if we focus more on those responsibilities and their mutualities and interlocks in a social context, we get a better understanding of how ‘rights’ actually work, and thence a better understanding of how to adjust those responsibilities dynamically according to context. That gives us the same outcome as ‘rights’, without any of the inherent dysfunctionalities of the ‘rights’-concept itself. We work with meshworks of interlocking mutual-responsibilities as if thy represent ‘rights’, whilst remaining carefully aware that the purported ‘rights’ never actually exist other than as description of a desired-outcome. In that specific sense, nothing changes: in essence, and overall, the outcomes do remain almost exactly the same. The only real difference is that a vast, vast, vast number of scams and dysfunctionalities fall exposed to plain air – including the notion that a government or anyone else has any ‘inherent right’ to force you to do something that you don’t want to do. There are no rights: there are only responsibilities – and it’s about time that we started being rather more honest about what, in a global human-and-other social context, those responsibilities really are.

Principle #3 is actually the root problem, around possession and paediarchy: everything else – including the mess of the money-economy – builds outward from that. It seems once again I need hammer home this point: there is no way to make a possession-based economy sustainable. It can’t be done – period. What we’ve done for the past few thousand years is give ourselves a nice illusion it can be done, by running an ‘infinite-growth’ pyramid-game: but on a finite planet, by definition, that must run out of room sometime – and a lot of the global indicators are flashing some very solid warnings that that ‘sometime’ is heading our way real fast and Real Soon Now. The models we have now are not viable: they can only work in an infinite world that doesn’t exist. So, all too literally, we do not have any choice about this: if we want to survive – and, if at all possible, thrive – we must change the fundamental architecture of the way all of us interact with this planet and each other.

All I’m saying here is that these are the constraints that we’re working with. They can’t be sideskipped, and they’re not negotiable: as I hope I’ve shown somewhat in the analysis in this series of posts, Reality Department makes it very plain that it isn’t offering us any viable alternative that doesn’t include those constraints. (Plenty of non-viable options, of course, which unfortunately are the inherent end-points of jus about everything you’re trying to hold on to above….) So that’s it: that’s what we have to work with – between us all, we somehow have to build an architecture that does work within those constraints.

You say: “Are we more ‘responsible’ if we subsume ourselves to a hive mind or just more subservient/dependent? How will decisions be made? What properties of this new organizational style will give us perfect insight and ensure optimal outcomes collectively, if not individually?” Answer: I don’t know. That’s what we have to find out, isn’t it?

You say: “ending individual liberties or “rights” in the name of saving humanity has been tried before”. That may well be true: but I’m not suggesting we do so. All I am suggesting we do is start to recognise the blunt reality that the entire concept of ‘rights’ doesn’t work, whether individual, collective or whatever.

You say: “Does anyone believe that we’d all be better off if a special class of people … should plan our existence and that could ever be fair/just or humane/ennobling”. My personal opinion is that I’d greatly doubt it, but I honestly don’t know. The nearest to that that I am saying in the previous posts, though, is that those of us with those types of skills should perhaps recognise their responsibilities to help gather and assess the facts and suchlike around this, so that the appropriate decisions can be made – which is not the same at all.

You say: “I’d rather have rights with responsibility, and the ability or at least potential for free people to continuously experiment (counter-entropy) in seeking a balanced society.” I don’t doubt it, and personally I would strongly agree with the point about ‘continuously experiment’. But you seem to have missed the point that there’s no dichotomy between rights and responsibilities: the ‘rights’ themselves are illusory, they don’t exist in any form other than as expressed through interlocking mutual responsibilities. (The only time when we can claim that there’s such a dichotomy is when we assert that the existence of ‘rights’ therefore allows us the absence of responsibilities – which breaks the very mutuality upon which the ‘rights’ actually depend.)

I know that you don’t want to believe me in any of this: fact is that it is fact – period. I know you’d want to dismiss all of this as some kind of daft utopian delusion: fact is that, as regards implementation, I make no assumptions at all – period. I know you’d like there to be an alternative that doesn’t involve fundamental change: fact is that there isn’t one – period. All I do know is that, as an architect, these are the constraints I have to deal with – period. First requirement, then, is start being honest about the fears around that – because that then gives us a chance to move on.

When I started this series, I did warn people that some of this would be seriously scary: and for many people – perhaps particularly in the US – this is what that ‘seriously scary’ looks like. I did try to make palatable, but I can’t change the facts – and these are the facts that we face. I’d suggest that how we face these facts – and how well we face these facts – provide a very good measure of how much we’re truly worthy of the name of ‘enterprise architect’.

Hi Tom – Thanks for the thoughtful response. I definitely did miss the recursive aspects of rights and responsibilities from what I had read – my bad if it was there in plain site. I like how you articulate them here, it helps me better understand your overall message.

I read your posts specifically looking for lateral insights so I’m certainly not predisposed to a negative response. Generally in our exchanges I’m supportive – though I’ve consistently pushed that Adaptability is the foundation, the sine qua non for most everything – the counter-entropy strategy that life itself depends on.

In our first phone chat several years back we crossed EA and politics and specifically talked about Rights and Responsibilities. It stuck with me and I thought you had veered, but it appears you just dug deeper so I’ll have to re-read.

I like societal critiques – Marx, Hegel but implementation is another matter. Like Winston Churchill said “No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”

I do feel deeply that a ‘good’ Society serves and exists to develop loosely-coupled citizens for their maximum potential, and the collective benefit is the by product of largely civil interactions of a free people. We should minimize constraints while require responsibility – the social compact between and across citizens. This is not perfectly implemented, but the model, by focusing on individuals, does allow for ‘shared understanding’ to evolve (or not) – that’s the beauty of it.

It’s a network architecture, hierarchies can be projected, but they are not fixed (big difference). Adaptability depends on this separation of physical structure from logical model – as does good EA and EITA.

I do have visceral dislike for the notion of a Philosopher King or illuminati that can save us from ourselves. It is abdication/surrender of the worst order alienating people from their own lives. Yeats captured it best – http://www.potw.org/archive/potw351.html

That’s my Weltanschauung.

Best,

Dave

Hi Dave

Thanks again! As for Peter and Len, apologies for the delay in replying.

And also as per my reply to Peter, I’d just like to re-iterate that I’m not attempting to design anything – all I’m doing is pointing out key constraints that I believe cannot be avoided, in any future social-construct, however and by whomever it happens to be constructed.

For example, there’s nothing whatsoever, in anything that I wrote in this series, that presupposes that a democracy is or is not valid. I do imply that a democracy (for example) would be non-viable if it fails to take appropriate account of those constraints, but that doesn’t in any way imply that democracy itself is non-viable – I hope that difference is clear by now?

I’d gently warn you against over-bundling political-format (e.g. democracy) with economic-format (e.g. possession-based economics): I know many people, especially in the US, would tend to think of it all as one package, but it’s not at all true. We have choices in both of those dimensions.

There’s also a strong tendency in the US to over-glamorise the myths of ‘the Founding Fathers’ as ‘the foundations of democracy’ and suchlike. I’d suggest it’s more useful to look at a much simpler, more prosaic and actually much older model, from what the Dutch call ‘polder-democracy’ – a democracy born out of practical necessity rather than high ideals. The polder is reclaimed-land, often at or below sea-level: and if you’re farming on the polder, you need to get rid of excess water, which won’t drain away on its own. The only place you can put it is on your neighbour’s farm; the only place he can put it is on his neighbour’s farm, who has to pass it on to her neighbour’s farm, all the way to where it can be pumped out to the sea. So everyone must cooperate, even if they don’t like each other at all, because if they don’t cooperate, everyone is in trouble. This is also the origin of local-government, because there’s a water-bailiff who helps people resolve disputes; and also the origin of national-government services, in the form of the Rijkswaterstaat, which manages the big-picture level of water-management.

I’m very careful at this point to avoid pejorative notions of ‘good’ or ‘not-good’ society. (I have my opinions, like everyone else, but it’s best to keep them out of this for now.) Instead, I’ve been focussing much more here on questions of viability – because almost by definition, any society that ignores those constraints ain’t going to be viable in the longer term, whether it’s nominally ‘good’ or not.

And yeah, I too have strong doubts about the delusions of the ‘Philosopher King’ (to which many US folks would place the ‘Founding Fathers’, of course… :wry-grin: ). I’d agree with you about how Yeats described the dangers in that delusion. But again, please, please recognise that that isn’t what I’m talking about here: I’m just talking about non-avoidable constraints – nothing more than that.

Hi Tom,

Thanks for the exchange. Not sure where the “Founding Fathers” reference comes from, I didn’t mention them or even the United States – I was channeling Friedrich Hayek, an Austrian, and Ronald Coase. Polder Democracy sounds good, but as you suggest Democracy at a local level generally boils down to that ‘practical’ version of ‘getting along’ (agreeing on responsibilities to each other / constraints on their individual activity), by necessity – people working as networks of individual and common interests. Imperfect and messy as that might be a loosely-coupled network is more efficient at course change than a singular institution. In that network there is room for voices, but no guarantees that a presumed ‘right’ argument prevails. Imperfect information/foresight create transaction costs.

Dave

Hi Dave – the bit about the ‘Founding Fathers’ wasn’t as a direct response to anything you’d said above, it was more about drawing a distinction between idealistic (e.g. ‘rights’-based) views of democracy, versus primarily pragmatic views (as in polder-democracy).

Probably the key point about polder-democracy and similar pragmatics is that whilst still has sort-of equivalents of both local and federal government, including judicial systems for dispute-resolution and enforcement, but they’re much more focussed and oriented towards a clear shared-outcome. In a sense, the ideals don’t get in the way! 🙂

Thank you (once again) for sharing. I like your analysis and the way you explain it, even though I have a different opinion. Besides all the negative aspects of human nature (and I think you have only elaborated a small portion of it) human nature also contains a willingness to communication and adaptability beyond anything else. This is (pity enough) not always used to the better, but it lets me believe that there is far more options in the future than we are cabable of truly seing: “Telling the future by looking at the past assumes that conditions remain constant. This is like driving a car by looking in the rearview mirror.”

So fear to loose the current is indeed a potential driver to change the behaviour, but I personally are more looking into all the great chances the future offers, knowing that I will not understand or even see most of it. And if I try to imagine a really bigger picture, than maybe human mankind is just the spores of the earth, to be send out into the universe to collide with lifeforms of other planets in one or the other form. Who knows, I don’t. Therefore I take day by day:

“Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree.” — Dr. Martin Luther King

Nice, Kai – thanks.

The only bit I’d comment on is this: “Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree.”

That isn’t just “day by day”: the whole point is that it has a strong commitment to the future – and respect of that future, too. It’s about responsibilities to that future – people who we might never see or know, but who would depend on our expressing this ‘response-ability’ right now. Times interweave, present, future, past: in part that’s what all of this is about.

Thanks again, anyway.

My “day to day” wording is most likely caused by lack of english knowledge. What I wanted to say is:

The present is the LAST moment of the past and the FIRST moment of the future. Therefore my advice is to live your live in the current with respect for the past and responsibility for the future:

Enterprise Architecting Past, Future or Present?”

Hi Tom,

I won’t argue (again 🙂 ) about the possession as a human nature thing because I may use a different interpretation (or scope) of the word possession different than you do in these articles. For me possession includes also having “natural”(inherited from our ancestors) abilities or talents which makes us different as a species, as groups and as individuals. My usage is in line with the argumentation on this page http://www.programmed-aging.org/theories/genetics_evolution.html which also contains this for EA relevant quote:

My feeling is that you are rightly saying that we must transform our market-based society in a kind of hunterer-gatherer society. This seems to be similar as the points made on this page http://libcom.org/history/hunter-gatherers-mythology-market-john-gowdy

I especially like this quote taken from that page:

Hi Peter

Apologies the late reply – I’ve been very much tied up on other things, only just had a chance to get back to it now.

Given your comments here, and those made by several others, I think there’s a key point here that I obviously haven’t managed to explain well enough. It’s this: I’m not trying to design anything. All I’ve done here is explain some key constraints that I see as being absolutely essential to address in any attempt at social design (such as via legislation, social-myth and the like) – because if we don’t address those constraints, the result automatically leads us back into the same mess (or an even worse mess) then we’re facing today.

Just to illustrate the point again:

— the constraint about ‘there are no rules’ isn’t a human-made constraint: it’s one that comes from Reality Department. Rules are just a made-up structure that attempts to pretend that change and uncertainty don’t exist. Uncertainty and change do exist. Hence this is a constraint that we can’t avoid.

— the constraint about ‘there are no rights’ is somewhat more human: it’s trying to deal with the blunt fact that, as yet another form of made-up rules, ‘rights’ are just a social fiction, which happens to be wide-open to all manner of increasingly-dysfunctional social-‘gaming’. The only way out of that mess is to go back to scratch, and recognise that whilst the concept of ‘rights’ is a potentially-useful social-fiction, as a convenient descriptor for a desired outcome, it cannot ever be divorced from or substitute for the meshwork of responsibilities through which that outcome may be achieved. All I’ve done there is indicate that we’re more likely to be able to achieve those desired-outcomes by focussing on the (real) responsibilities rather than the (fictional) ‘rights’.

— the constraint about ‘money doesn’t matter’ is a direct corollary from the above two points: money is an overlay on barter which is an overlay on purported ‘rights of possession’ that are, equally just another social-fiction based on another made-up social-rule – there’s nothing ‘real’ behind it at all, the whole thing is held together by a meshwork of evasions of social-responsibility that, to be blunt, is literally no different than theft on an unimaginable scale. In short, it’s not a stable foundation for a global economy – a fact which is fast becoming inescapably obvious, no matter how much people still try to hide from that fact. All I’ve done is suggest that it might be useful to recognise that the ‘possession’ overlay is inherently so dysfunctional that it can only be made to seem viable by running it as a pyramid-game – and like all pyramid-games, very nasty things happen when a pyramid-game draws to a close, and they get very much nastier the further into the collapse the game is allowed to play (global resource-wars, anyone?). Reality Department is making it clear that that’s a non-negotiable constraint – or rather, every would-be ‘solution’ that tries to sidestep that constraint ends up in something really nasty, hence in practice we do have to treat it as a non-negotiable constraint.

— the ‘adaptability is everything’ constraint is, again, just a recognition that change is a non-negotiable fact of Reality Department: hence probably wise to learn to work with it rather than rail in futility against it?

So yes, we might end up with something like a gatherer-hunter culture; but we might also end up with a highly technocratic culture. I really don’t know, and to me honest I don’t have any especially strong opinions at present about ‘best’ structures or suchlike. All I do know is that unless they take those constraints above fully into consideration, they’re dead. As are we all, if the present structures continue for much longer. Fairly straightforward, really.

Tom,

I made my last comment mainly because I was glad I found an article that seems to be addressing some similar points as you do.

My problem* is that I need some example(s) (sketches, models, prototypes) to understand how a world could look like if it was based on your four principles to really understand you. Now it is too theoretical/philosophic for me.

*And my (being here as a student to learn)is your problem according to Chris Crawford in On Interactive Storytelling (see the paragraph At Last, Narrative p6-13) 🙂