Control, complex, chaotic

What exactly is ‘the chaotic’ in enterprise-architectures? How do we work with it, design for it rather than ‘against’ it?

Yeah, I know this is a theme I’ve visited often here, but to me it’s a challenge that’s right at the core of all of our current approaches to enterprise-architectures and the like. What triggered it this time was a great conversation with Nigel Green, in our back-and-forth comments to the post ‘More keywords for SCAN‘, and also in that, in looking for a worked-example for an upcoming conference, I came back to the seemingly-endless problems with the UK National Health Service (NHS).

I won’t go into any detail on the NHS’ travails here: many of them are well-known, such as the ongoing disaster-area of its would-be information-systems, and the disastrous misadventure of trying to measure and ‘control’ health-delivery performance in terms of predefined targets. The NHS started out some 65 years ago with the powerful vision of ‘health-care for all, free at the point of delivery‘, yet that vision has been so much whittled away by politicians and others over the years that it’s now best described as a highly-politicised mess of competing interests in which, all too often, the health-needs of patients have ended up at the bottom of the stack. Oh well…

There’s a lot that needs to be done to make the NHS workable again, of which perhaps the most important would be to properly refocus on that original vision. Over the next few weeks, I’ll use this as a worked-example on how to apply enterprise-architecture thinking and methods, at very large scale, and beyond IT-alone, to tackle a major strategic review for any organisation, and how to link all the way from strategy to execution and back again, so as to bring that organisation ‘back on track’ to its real aims.

For here, though, there’s one point that’s really striking, and which is more about mindset than method. Many people have (correctly, to my mind) identified some of the core problems of the NHS as arising from misguided attempts to ‘control’ the inherently-complex: the ever-increasing managerialisation of the service, the disastrous impacts of misguided ‘targets’, or the all-too-frequent failures to deal with inherent wicked-problems as wicked-problems – for example, pharmaceuticals-manufacturers wanting to maximise profits, against the the Service’s desperate need to manage spiralling costs; or the diagnostic capabilities of new technologies creating a spiralling problem of ‘too much medicine‘, “the threat to human health posed by overdiagnosis and the waste of resources on unnecessary care”. Attempting to ‘control’ complexity just doesn’t work: we need to treat the complex as complex, not as a ‘controllable problem for which we don’t quite know all the rules (but will know them all Real Soon Now, honest…)’.

Yet I’m also noticing another deeper problem: misguided attempts to apply complexity-theory to things that are neither rule-bound control nor pattern-based complexity, but are inherently ‘chaotic’ – a ‘market-of-one‘. Although we can identify definite patterns in health and health-care – that’s the whole basis of epidemiology, for example – neither rules nor statistics can help us deal with the blunt fact the everyone is different. The kind of patterns that we’d use in a complexity-model – probabilities, Bell-curve distributions, outliers, all that kind of thing – can all too easily mask the real underlying fact of uniqueness, from which that supposed ‘pattern’ will actually arise: somewhat like the barely-visible deep-randomness that underlies the visible patterns of Brownian-motion.

This is actually where the difference between complexity-theory and real-world practice ended up forcing me to part company with complexity-oriented frameworks such as Cynefin. They seemed to interpret ‘chaos’ solely as a feed into their own models of complexity, whereas I was finding uniqueness – or, to use Common Ground‘s terms, particularity or distinctiveness – as an inescapable fact that I needed to deal with in its own right. Uniqueness – the ‘chaotic’ – cannot be reduced to complexity or control.

One example of the ‘gotchas’ here, that’s commonly used both in concepts of ‘control’ and of complexity, is ‘Occam’s Razor‘:

“among competing hypotheses, the one that makes the fewest assumptions should be selected”

Yet on its own, as Steve Nimmons warned some while ago, Occam’s Razor is a proven anti-pattern in enterprise-architecture. To make it work in real-world conditions, we need to balance it with a better awareness of uniqueness and difference, such as in the ‘anti-razor’ of ‘Hickam’s dictum‘:

“patients can have as many diseases as they damn well please”

Yes, every patient will have similarities with others; yet they are also different to all others, unique, themselves. ‘Similar’ is not the same as ‘the same’ – it’s ‘same and different’, both at the same time. Which means that whilst the needs of each patient may be similar to others, and hence need treatment that’s similar to those of others, they’re also different, unique, not the same as any other. Which, in turn, means that any health-delivery mechanism that assumes that everyone is the same (‘control’) or fits with some kind of predeterminable pattern (‘complexity’) is going to deliver the wrong treatment for that unique person, quite a lot of the time.

The same is true in sales: every sale is ultimately a market-of-one. The same is true in business-models: the whole point there is to differentiate from others, to not be the same as everyone else – even though we need to trade via the same standards and suchlike. I’ve come across this same theme time after time in many other guises: for example, Australian researchers are world-leaders on ‘ageing-aircraft syndrome’ – not just corrosion, or fatigue, or mechanical-damage, but the ways in which each of these and other relatively-predictable factors interact in each unique case. Attempting to apply ‘control’ or ‘complexity’ to the chaotic just doesn’t work: we need to treat the unique as unique, not as something that’s resolvable by a ‘control’-based or complexity-pattern-based ‘solution’.

In sense, what we need here is a kind of uniqueness-oriented equivalent of complex-adaptive systems: we might call it chaotic-adaptive systems, perhaps. One possible source of ideas here is ‘‘pataphysics‘:

“‘Pataphysics seeks … to view each event in the universe as completely unique, subject to no laws but its own … the science of the particular [rather than] the only science … of the general … not the rules governing the general recurrence of a periodic incident (the expected case) as the games governing the special occurrence of a sporadic accident (the excepted case).”

The catch is that, by intent, ‘pataphysics is more of a parody of science than a true science in its own right – hardly surprising, given that its origins were in Absurdist theatre… Yet there are distinct disciplines around it, such as the psychogeography work of the Situationists and, more recently, the writer Will Self – or, again, as documented in Common Ground’s work on ‘particularity’ and ‘local distinctiveness‘. Perhaps not a science in the conventional sense, then, but still capable of explicit disciplines that are fully-compatible with the sciences. Probably quite a lot more that needs to be done there to make it more accessible to others, though.

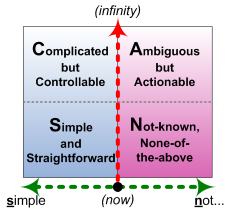

At this point it might also be useful to look at this in terms of the SCAN framework:

Another way to look at the axes in SCAN, that’s more compatible with what we’re working with here, is to redescribe them as follows:

- horizontal-axis: from same to different – identical (far left) to unique (far right)

- vertical-axis: from theory to practice – infinite available-time-before-action (‘infinity’ – e.g. analysis-paralysis) to ‘NOW!‘ moment-of-action (baseline)

Which, in terms of the domains, gives us:

- Simple: real-time rule-based decisions, suitable only for identical or near-identical contexts

- Complicated: non-real-time algorithmic decisions (with computer-automation enabling it to get closer to but not at real-time), suitable for high-variety yet still predictable contexts

- Ambiguous: non-real-time pattern-based decisions (with computer-based pattern-matching enabling it to get closer to but not at real-time), suitable for ‘complex’-type contexts

- Not-known: real-time principle-based decisions, suitable for potentially-unique or ‘chaotic’ contexts

Note that every real-world context will have a mix of Simple, Complicated, Ambiguous and Not-known: which means that we’ll need an equivalent mix of matching techniques to ‘solve’ and/or resolve the whole of the context. (We don’t say that a context ‘is’ Simple or whatever – solely ‘in’ one domain or another – because that all but guarantees some form of mismatch-failure further down the line.)

The catch, in practice, is that whilst in most enterprise-architecture contexts we do have many well-identified techniques for ‘control’ (Simple and Complicated), and increasing awareness of techniques for ‘complex’ (Ambiguous) – if perhaps still too much reluctance to use those complexity-oriented techniques – we still don’t have much if any awareness either of techniques to work on the ‘chaotic’ (Not-known), or of how and where and when to use them. That’s a real challenge that I’d suggest enterprise-architects and others definitely do need to start looking at right now.

Comments, anyone?

Your comment about the NHS resonates with me, as I spent the early part of this week navigating between my GP, a private insurance company (courtesy of my husband’s employee healthcare scheme), my physiotherapist and a local diagnostic centre to get an ultrasound scan and ensure the results of it end up in the right place. This requires the patient to actively steer herself through it, by remembering to ask the right questions of each health practitioner they meet about what happens next, and working to the constraints that are in play.

To adopt the language that you often use, what’s needed is a way of improving the overall enterprise of healthcare in the UK, not just the NHS, so we get the best value from all the resources available. The problem with the NHS (as with the MOD) is that it isn’t an organisation, it’s a collection of organisations.

Your comments about your NHS experience immediately brings to mind Chris Potts’ dictum about “Customers do not appear in our processes, we appear in their experiences”. The whole problem here is that the client (or however we should describe her in this context) is left to fill in a vast array of clunky gaps between different organisations’ self-centric ‘inside-out’ processes: not exactly a happy experience…

And yes, this point about ‘an enterprise of enterprises’, or ‘an organisation of organisations’ is really important. That’s the definition that DoDAF uses, I think? – they use ‘enterprise’ as a synonym for ‘organisation’ (which I think is not a good idea) but they do at least acknowledge the idea that that kind of enterprise can incorporate other enterprises, within other other enterprises, and so on. That pretty much describes the health-system: a vast number of organisations within organisations that make up the consortium that is the NHS itself, plus all of the private-medicine providers, the drug-companies, local pharmacists and everything else. It’s a huge scope, yet still in effect a single story. It’s that juxtaposition that I really look at here, in exploring the overall enterprise of ‘the NHS’.

I’ll settle for “yes” – to everything. Good post, good points, good timing. In particular I’d echo your call to action in the last paragraph. Working on it. As are you.

Yep. We’ll keep in touch on that, of course. 🙂

Cartography has a long history of dealing with the unknown (terra incognita), see http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/shackletonexped/surviving/mapping.html for an example how imaginative geographers boldly declared the existence of Antartica ages before somebody really saw it.

Nice examples, Peter – thanks. (And yes, lots of ‘terror incognita’ we still need to face here, I suspect? 🙂 )

The target problem / example problem interests me. I have had longstanding exposure to varying part of the health ecosystem in Audtralia, including specialist areas such as aged care, mental health, disability services, etc. So I am aware of some of the challenges and approaches. I have come to understand some of the unique and variable characteristcs through working with a cancer registry.

Equally, I am aware of some of the inherent problems arising from our continually improving capabilities for preventing and treating conditions, and our inability to place a value on life, and hence, therefore to evaluate whether it is “worth” treating a condition.

So, quite interest to explore this area. My own experience is that part of the challenge is in how we frame problems and how we think about resolving them.

I enjoy the challenge of dealing with these seemingly intractable problems which are critical to the future of our society. Whether the SCAN line of thinking is the way, either in demonstrating the need for different tools, or considering what these tools might be.

@Peter: “My own experience is that part of the challenge is in how we frame problems and how we think about resolving them.”

Yes, exactly.

@Peter: “Whether the SCAN line of thinking is the way, either in demonstrating the need for different tools, or considering what these tools might be.”

SCAN is just tool amongst many: I hope it’s useful for some people and some purposes, that’s all. And yes, I do hope it’s useful in helping us to select other tools that are appropriate for the respective need: but I won’t claim it’s any more ‘special’ than that! 🙂

Again, it’s just a tool: it’s how we use tools that matters, much more than the tool itself. And the ‘why’ behind the use of that tool, of course: that matters even more than the ‘how’.