NOTES – putting it into practice

How do we use an narrative approach in enterprise-transformation? What’s different about it, in real-world practice? How does it work?

In the first post in this series, I introduced the core ideas for NOTES – Narrative-Oriented Transformation of Enterprise (and) Services – as an alternative approach for enterprise-architecture and the like.

[The reason why I’ve proposed this approach is that it matches more closely to the way that most people think about enterprises and other collaborations – as a shared-story, rather than as a machine or a technical structure.

This doesn’t ignore the value or importance of modelling the technical and other structures of the enterprise – those are very necessary indeed, as any practical architect would tell us. More, think of it as a complement to the existing work on technical-architecture – not as a substitute for technical-architecture. Yet also as a necessary complement to technical-architecture, because the reality is that technical-architecture is not complete on its own: in an all too literal sense, it’s missing its story. That’s what and why we’re working with this here.]

A quick recap on the core themes:

- “the world is made of stories” – as with a service-oriented approach to architecture, a narrative-oriented approach can apply to every aspect of an architecture, and at every level

- the enterprise itself is a story – there’s an overarching theme or premise or ‘promise’ that connects between everyone and everything within the same enterprise

- the enterprise is an ongoing story of relations between people – or, alternatively, of relations between the various actors of the enterprise-story

- the enterprise-story is made up of smaller stories – the scenes or story-lines which, in a more conventional view of architecture, we might describe as the processes of the enterprise

- the enterprise-story takes place in a specific setting – the stage and its context (technology), location, props (artefacts) and suchlike

- stories thrive on conflict, tension and uncertainty – in contrast to machines, which generally don’t

Some quick practical takeaways from this, that we can use straight away in enterprise-architecture and business-transformation:

— What’s the story? – If the enterprise itself is a story, and one that connects between everyone and everything in the shared-enterprise, then it’s kinda important to know what that story is… One practical suggestion for a starting-point is to identify a kind of ‘tag-line’ or ‘shared-vision’ that has three distinct components:

- concern or focus: what is of interest to everyone in the enterprise? – what is it that links everyone together in ‘common cause’?

- action: what is being done to or with or about that concern or focus? – how is this being done?

- qualifier: what is it that makes doing these actions to or with this concern so important to everyone? – why is this being done?

A classic example of this is the TED vision of ‘ideas worth spreading’:

- ideas [what: concern]: everyone is focussed on or concerned about ideas

- spreading [how: action]: everyone is concerned with spreading ideas

- worth [why: qualifier]: everyone is concerned about spreading these ideas, because there are ideas that are worth spreading

What’s the equivalent tag-line or vision for the shared-enterprise within which your own organisation operates?

— Whose story? – if the enterprise is a story, who holds to that story? Who values it? Why do they value it? How does that story guide their sensemaking and decision-making?

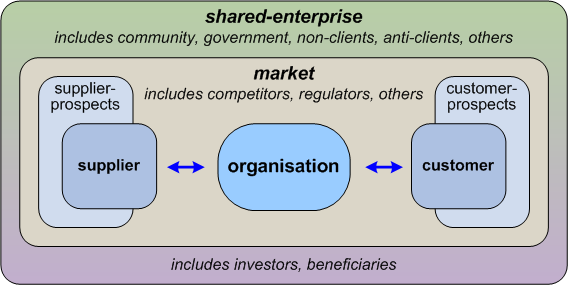

This is where a broader view of ‘the enterprise’ can greatly help to establish the organisation’s real business-context:

Who are all the actors in this story? What are the relationships between them? How does this one story link all of them together, and in what ways?

— What drives the story onward? – what keeps the story going? For most enterprises, the story isn’t a Hollywood-style ‘one-shot’ progression to a single goal, but something more like a cross between a serial and a series: a continuing story, usually with much the same actors (and occasional guest-actors), yet also split into identifiable ‘chunks’ of activity – a scene, a story-beat, an episode – each with their own ‘beginning’, ‘middle’ and end’.

In which case, what are the ‘chunks’ of activity in your enterprise-story? Who are the actors – human and otherwise – within each ‘story-chunk’? What drives each of their choices and actions? How does this drive the story-chunk ever onward, from its beginning to its middle to its end?

(Or, for that matter, how we know what is the respective ‘beginning’, ‘middle’ and ‘end’ for each story-chunk? What events tell us that these transitions have taken place?)

What is it that links each of these story-chunks together? – and in which form of link:

- as continuations, where one story-chunk’s ‘end’ leads to another’s ‘beginning’

- as layerings, where one story-chunk forms part of a larger-scope chunk (scene to story-beat to episode to overall-story) or smaller-scope chunk (overall-story to episode to story-beat to scene to individual-action)

- as throughlines, where specific actions or behaviours or story-chunks provide a ‘character-arc’ or continuing-story for one specific actor or related clusters or actors

For your own organisation, within its shared-enterprise, how do you ensure that every choice and action drives the story forward, and links to and supports the vision and promise of the shared-story?

— What is the setting for your part of the shared-story? – using the metaphor of the stage as a setting for ‘the theatre of everyday life’, what are your organisation’s equivalents for:

- the proscenium – the visible stage on which the ‘main action’ takes place

- the backstage area – where everything is set up for the action to take place, but often should not be visible at all

- the stage-door area – where actors enter and leave, before and after taking on their role in the visible action

- the audience area – a space for those who watch the action, and often judge the quality of the action, but do not themselves take much if any part in it

- the front-of-house area – where people are invited to the show

- the theatre-building – the overall framing of your organisation’s story

- the theatre-context – the city-district or campus or whatever in which the theatre-building itself is set

What assets, functions, capabilities and services are needed, from whom, and with whom, to make all of this happen, such that “it’ll all go right on the night”?

— What conflicts, challenges and uncertainties underpin the overall story? – and each and every part of the story? How do each of these help to drive the story onward?

In mainstream views of business, such conflicts and uncertainties are, of course, what we’d often most strive to remove. And yet if we were ever to succeed in doing so, we would actually kill the story – or, at best, we’d reduce it (to quote one of the old Goon Show scripts) to “a cardboard replica of itself”. The reality is that uncertainty is everywhere, is a fact of life: hence the popular pretence that it does not and cannot exist is not exactly realistic… And the tension between ‘what is’ versus ‘what could be’ is the real driver that underlies the story that is the enterprise itself: rather than fighting in futility against that tension, we need to learn how to work with it. Which is where a story-oriented view of the enterprise comes into the picture.

And finally, a quick reprise on some core basics:

- a common structured-oriented view describes the enterprise in terms of people, process and technology

- (and, yes, too many so-called ‘EA’ frameworks would describe it solely in terms of IT, more-IT and yet-more-IT…)

- a story-oriented view describes the enterprise more in terms of actors, story-lines and stage, within an overall story-world

So whenever we see a reference to ‘people‘, think in terms of actors – Who are the actors in this enterprise-story? Once again, what are their relationships with each other, with the story as a whole? What do they exchange with each other? – or not exchange? – and why? How do their actions and choices drive the story forward?

Whenever we see a reference to ‘process‘, think in terms of story-line – What are the story-lines here? What part does each actor play in each story-line – and line of the story? If this was a stage-play or a film-script, what could we do to tighten it up, make it more taut, more terse, more tense – even in the freer-flowing parts of the story? What can you do to avoid ‘plot-holes’, to prevent gaps in the story?

And whenever we see a reference to ‘technology‘, think in terms of stage – What is the stage on which the story is set? What role does each form of technology and facilities and other assets play in the staging of the story? In what ways would the story change if it was staged a different way? In what ways does the stage become visible as part of the story, and then itself disappear into the background to provide a barely-noticed backdrop to the action?

(Yes, agreed, some technology can be active too, more ‘actor’ than ‘stage’ – but we’ll come back to that when we explore the notion of ‘actor’ in more depth in another post.)

Enough to get started with, I hope? – more later, anyway.

And now over to you for your comments, perhaps?

Hi Tom — I think the simple version of this is what you say at the end — processes are stories about what people do. I had occasion today to remember a period in my career when my team created a lot of swim-lane models in a phone company. People liked seeing themselves and their work in the context of upstream and downstream work, so reviewing these models was always joyful and boisterous. We eventually trained about 200 people to make their own, and soon whole walls of the HQ building were covered with 8, 10, 12-foot long drawings with up to dozens of work groups and applications that had to interact to provision complex services, etc. People really like these “work stories”. There was no resistance, but rather joy in this activity. Hard work, yes, but joyful work.