Business Model Canvas beyond startups – Part 1

Is Business Model Canvas at risk of becoming another TOGAF – a useful tool for a specific context, yet often more of a hindrance than a help wherever people try to use it beyond its original purpose? And if so, what can we do to limit the damage – or, preferably, make it more reliable for those broader uses?

Don’t get me wrong: like TOGAF, there should be no doubt that Business Model Canvas works well for its original context – commercial business-startups, in that latter case. The problem is that people very often try to use it for business-contexts that aren’t commercial-startups, yet without much apparent awareness or understanding of the built-in assumptions and subtle short-cuts that help to make it so powerful and so useful in the startup space. Oops…

And hidden assumptions can be very bad news indeed. Sure, we can use Business Model Canvas [BMC] as a base for just about everything in business-architecture: it does allow us that kind of affordance. Yet to shift metaphors a bit, we can use a hammer as a screwdriver, but we’d better be aware of the implications of doing so – otherwise things might well come apart in some expensively ‘unexpected’ ways. Hence why the built-in limitations of BMC can be a very real business concern.

I’ve written about various aspects of this in the past here, but the start-point this time was a great email back-and-forth with innovation-consultant Paul Hobcraft, particularly about the ‘back-end problem’ – BMC’s lack of support for modelling what we need to do to implement a business-model in real-world practice.

I’m paraphrasing somewhat here, but Paul’s view seems to be that although BMC has severe limitations, it’s now so much of a business-architecture ‘standard’ that, much as with TOGAF and enterprise-architecture, we have to find a way to work with it – or round it – whether we like it or not. He’s described his suggestions on this in several of his blog-posts, particularly:

- Multiple use of the Business Model Canvas

- Juggling around business-model design

- The (re)birth of the architect for the business-model design

- The understated back-end for the Business Model Canvas

- The age of large business-model reinvention

For anyone involved in business-architecture and innovation, I’d suggest that all of those posts are ‘must-read‘. Yet whilst I’d agree that his approach – and in particular his eight ‘multiple uses of BMC’ – would work well at the CxO level, I’m not so sure that it would work as well elsewhere.

For example, some of the most common web-queries to this weblog are about how to use BMC for non-profits – and yet just about everything in BMC assumes that only commercial businesses have business-models. (The only exception I’ve seen in the Business Model Generation book is three paragraphs on p.264, on ‘Beyond-Profit Business Models’ – and even that is solely about how to manage the monetary aspects of a non-profit’s business-model.)

And the whole of the huge tasks of implementation – without which a business model simply cannot work – is given no more than a cursory four-page skim (p.270-273). That’s nowhere near enough for enterprise-architecture usage, particularly at a whole-of-enterprise scope – we need consistency at every level and across every domain. Yet in practice, and in part by intent and design, BMC really only works at the ‘big-picture’ level’: trying to use it recursively, in a nested way – to map services and operating-models as ‘business-models within business-models’ – rapidly becomes a painful exercise in pointless frustration, as I’ve often found to my cost.

So for enterprise-architecture, the dilemma I’m stuck with is this:

- Do we apply various add-ons and tweaks to kludge Business Model Canvas enough to make it work at other scopes and scales? – but risk breaking its usefulness as a ‘standard’ if we do so?

- Do we start again from scratch, providing ‘translation’ to and from BMC at the big-picture level only? – but risk disconnect from the ‘standard’ entirely?

Somewhat strangely, the best way through the dilemma seems to be to do a mixture of both.

My own version of ‘start again from scratch’ is Enterprise Canvas. It’s based on a service-oriented approach to mapping the enterprise, all the way from the core vision and values of the shared-enterprise, right down to an individual action or individual line of code – in other words, both far ‘above’ and far ‘below’ the BMC’s scope.

The catch is that although it’s consistent at every level, there’s a lot more to it than BMC, and as yet it’s still not as simple to use: it’s still a tool more for enterprise-architects than business-model hackers. I’m workin’ on that – as I hope to be able to show in the next few weeks and months – but the reality is that there’s still some way to go. At present, I’d still recommend to start the business model with Business Model Canvas, and then move into Enterprise Canvas and/or other model-types once you start to dive down into the detail.

But the catch with that – starting with BMC – is that it still doesn’t resolve the problems with BMC itself: usage for non-profits and large organisations and so on. So that’s where those ‘add-ons and tweaks and kludges’ come into the picture: and they also show why we need to complement BMC with Enterprise Canvas, and what needs to be added to and underpin both in order to make them work in real-world practice.

So let’s explore what’s needed to tweak Business Model Canvas to work for these other uses: though also we must always bear in mind that all of these usages are ‘non-standard’ – and hence our responsibility, not anyone else’s!

Overview

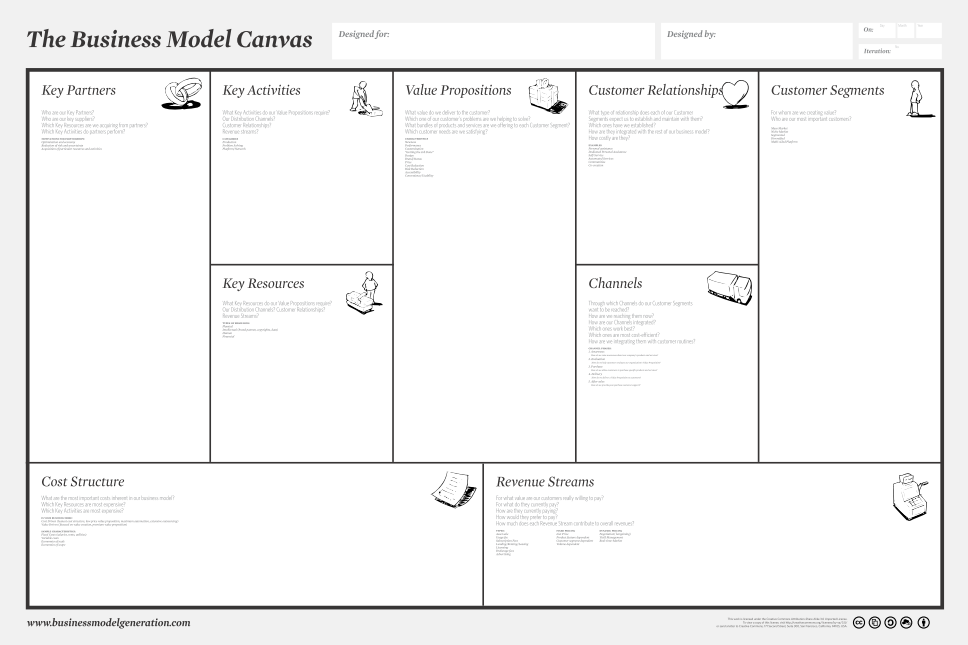

For those who aren’t already familiar with it, the Business Model Canvas is a visual frame containing nine ‘building-blocks’ for a business-model:

The idea is that – typically in an interactive-workshop environment – we would explore the overall business-context, and place sticky-notes on the various building-block segments of the Canvas to build a model of how the business would work, iterating towards a viable and profitable business-model. The definition on p.14 of the Business Model Generation book is as follows:

A business model describes the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers and captures value.

Note a subtle yet crucial point here: “creates, delivers and captures value” – not “money“. It’s utterly crucial, in all business contexts, to understand that money is only one subset of value – and that whilst all forms of value may interact, and may often be convertible from one form to another, not all forms of business-critical value can be converted to monetary form. Yet this is where – on p.15 of the book – Business Model Canvas risks being dangerously incomplete and dangerously misleading:

We believe a business model can best be described through nine basic building blocks that show the logic of how a company intends to make money.

“Nine building blocks” is fine; but “the logic of how a company intends to make money” isn’t, because ‘value’ is not the same as ‘money’. At best, money is a proxy for some forms of value – not a substitute for any of them. We ‘make money’ as an outcome of how we ‘create, deliver and capture value’: the linkage between ‘value’ and ‘money’ is indirect, not direct, and if we ever get this point wrong, we have a business-model that is all but guaranteed to fail – yet probably have no means to understand why it will fail.

The distinction is perhaps easier to understand with the building-block structure in Enterprise Canvas:

In essence, the business-model in Business Model Canvas describes only the central section in Enterprise Canvas, the ‘value-flow’ interactions. Yet as can be seen above, the bit about ‘making money’ – ‘profit’, or, in Enterprise Canvas, the relationship between ‘investment’ and monetary ‘dividend’ – actually takes place through another set of interactions that are mostly beyond the scope of BMC itself. And they’re not the same flows: profit-capture is not the same as value-capture. In practice, if we confuse money with value, and try to interpret every form of value solely in monetary terms, what we’re likely to end up with is a Taylorist-type business-structure – one that’s still all too common in large organisations – that is literally back-to-front and upside-down:

Unfortunately, if ‘value’ is equated with ‘money’, a business-model in Business Model Canvas must inherently drive towards that type of dysfunctional structure. Hence why viewing value as value in its own terms – and not solely as translated into monetary metrics – is so crucially important in business-architectures.

Another key advantage of breaking free from a money-centric view of business-models is that doing so enables us to understand that the distinction between so-called ‘for-profit’ and ‘not-for-profit’ organisations is not only meaningless, but dangerously misleading. Every organisation is ‘for-profit’ – the core difference is not in the nature or structure of the organisation itself, but in the value-models that underpin the definition of ‘profit’ in each case. Once we understand this, we can use Business Model Canvas to develop business-models for ‘non-profits’. The complication is that the definition of the respective value-model is usually outside of the scope of the BMC itself – a concern that we’ll look at in more depth when we explore the BMC’s Value Propositions building-block.

To use Business Model Canvas in existing organisations, we build further on that distinction between ‘value’ and ‘money’, and link it more firmly to shared-values – as indicated in the upper section of Enterprise Canvas. Crucially, these are the values shared with the broader enterprise, several steps larger than the organisation itself – the ‘ecosystem-with-purpose’ within which the organisation operates. In practice, this means that when working with Business Model Canvas, we also need to take into account:

- direction: how to develop the business, change the business and run the business day-by-day at every level

- coordination: how coordinate development and change, and between processes and silos

- validation: how to keep on track to qualitative concerns such as safety, security, financial-probity, business-ethics, quality of service, environment, waste-minimisation and much more

Without those, the business-model will fail – especially as the business grows in scale.

For an existing organisation, other themes we’ll likely also need to assess would include:

- misalignment risks: a business-model that does not align with existing values might work well in another organisation, or a new organisation, but not with this one

- ‘cannibalisation’ risks: a new business-model might place existing business too much at risk, creating an overall negative return for the organisation

- timing risks: a new business-model, even if intended to replace an existing one, may cause a cash-flow ‘hole’, where the income from the old business winds down faster than the new business-model can come on-stream

- ‘local-optimisation’ risks: a new business-model in one area of the organisation may be successful in its own terms, but damages the viability of other aspects of the overall business

- political risks: a new business-model could inadvertently cause disaffection or industrial disputes in other parts of the organisation, or intrude on some other silo’s ‘turf’

Typically, these are concerns that become visible only at the whole-of-organisation level, or even whole-of-enterprise level – and hence often considered ‘out of scope’ for the business-model itself. In reality, they cannot be dismissed as ‘out of scope’, because in practice the business-model won’t work unless we do address these concerns!

Enough for now, anyway: in Part 2 we’ll explore how this comes out in practice block-by-block in Business Model Canvas.

HI Tom – I apologize for the long post:

Thanks for a very enlightening post. I believe your thoughts on implementation and integration of business design and business architecture are significant and very interesting.

I do feel I have to address a couple of items raised in this blog regarding the origin and use of the canvas and a couple of other items.

On the canvas

Not to put too fine a point on it, but the canvas was not originally designed with startups in mind. The original thesis, the ontology, was intended to create a common mental model for the concept of business model that would allow existing business to have a common language and externalized construct to look, strategically, at their businesses. The thesis also contained a number of models used to analyse the business model for its strength and effectiveness. I see this as somewhat of a vertical look at a business model.

The book Business Model Generation moved the discussion in three ways. The business model construct of the thesis became the business model canvas. The second change was the addition of patterns to the discussion. The third change was the perspective. BMG took the consideration of BMs into more of a horizontal perspective of how one changes models over time. To do this the book addresses strategy, tools, techniques, and process. The focus on existing business models is evident in stage 2 of the process – understanding the current model.

One of the active challenges to BMG when it first came out was from the startup community who felt BMG didn’t address their needs. It wasn’t until Alex began his collaboration with Steve Blank that a focus on startups became very popular. (t was driven by Bank’s customer development model and the amazing popularization of that approach that raised the startup profile of BMG).

On value

You make a great point about value may include more than money. In a third party funded model (typically government or not-for-profits) where this is most evident as party A pays party B to deliver good/services to party C. Party B may get no financial value from party C but must capture information about the deliver of value to prove to party A they have accomplished their goal. Too often governments and N-F-P orgs forget to build that value (data) capture into their business model.

On non-commercial enterprises

I have used the canvas with all sectors, private (for profit), not-for-profit, social innovation and government, without having to modify the canvas. I have also used the canvas with startups, entrepreneurs in existing orgs, government agencies, and existing companies.

On BMG & Architecture

The key here is to understand the canvas, as a tool of business design, is a strategic not an implementation level conversation. The value of the canvas is the strategic conversation that are driven by consideration of the core elements of the canvas, and how these elements interact with each other to accomplish a vision. How that logic is implemented can be seen as the domain of architecture and what is needed most, as you have so importantly pointed out, is a way to translate that design into implementation – the compelling purpose for the Enterprise Canavas.

Mike