Dotting the joins (the JEA version)

[The new editor of the Journal of Enterprise Architecture, Len Fehskens, asked me to expand my previous post ‘Dotting the joins‘ into a formal paper for the Journal. Which I did, and it was duly published in the August 2013 edition – so here’s the full-text of that article. (Note that, for copyright reasons, this is the only place, other than the Journal, where I’m allowed to publish this version of the article.) Hope it’s useful, anyway!]

Dotting the joins: the adverse effects of specialization

Tom Graves

Abstract

Specialisation is often seen as the natural way to deal with the demands of real-world practice and real-world complexity: we’ll often choose specific ‘subject-areas’ to specialise in from school-days onwards. Yet that choice is not without its consequences: for example, we’ll often hear about the need to ‘join the dots’ between the different domains and disciplines and other specialisms. This article explores some of the adverse effects of specialisation, and what we can do to mitigate them within our enterprise-architectures.

Joining the dots

Have we gone dotty – all of us? I have to wonder sometimes…

Here I am, stuck in the aptly-named waiting-room at the local clinic, the appointment-time having passed more than hour ago for the routine blood-test that’s yet another disjointed part in my routine annual health-check. I’m pondering idly on how the term ‘patient’ has somehow changed from noun to enforced-adjective, and how the National Health Service here in Britain has seemingly all but lost track of the meaning of either ‘National’, Health’ or ‘Service’. Sigh…

In short, not happy.

The woman next to me is faring even worse. She’s been here almost every day this week, she says, having different diagnostics done for different specialists. She thinks it’s an ordinary stomach-pain that will clear up on its own some time soon, but she’d thought she’d better check. Now she’s not so sure that that was a good idea, because all that’s happening is that she’s going round and round in circles, bouncing like a pinball between different departments, in a tortuous, tedious, timewasting mess that’s hugely expensive for everyone involved.

And no-one’s telling her anything – after all, she’s just the patient, isn’t she? – and no-one’s doing anything to help her join up the dots enough to bring this nightmare to an end. Why oh why do we do this to ourselves, and to each other? Crazy-making… crazy indeed.

Join up the dots… My eye falls on an abandoned magazine a couple of seats away. It’s open at the ‘children’s puzzles’ page, and some child has been at it, all right: a random scrawl of coloured pens across the ‘colouring-in’ picture, and wobbly lines connecting between the dots in the join-the-dots puzzle. From the pre-printed pattern, the picture looks like it’s supposed to be a doctor, but with half of those wavy lines failing to join up with their dots it’s kinda difficult to tell. A bit like the health-service itself these days, in fact. Hmm…

Wait a minute, though – haven’t we got this back to front? We’re trying to join up the dots, when the real problem is that we keep dotting the joins – breaking things up into small and smaller and ever-smaller supposedly-’controllable’ chunks, and then losing track of any sense of the whole-as-whole?

Yeah – that’s something we definitely need to explore if we’re to have any chance of getting out of this mess…

Dotting the joins

To do something – to do anything, really – we need to know enough to get it to work right down in the detail of real-world practice. When there’s a lot of detail to learn, or a lot of complexity, we specialise: we choose one part of the problem, one part of the context, and concentrate on that. We get better at doing that one thing; and then better; and better again. And everyone can be a specialist in something – hence, given enough specialists, it seems that between us we should be able to do anything. In that sense, specialisation seems to be the way to get things done – the right way, the only way.

Yet there’s a catch. What specialisation really does is that it clusters all of its attention in one small area, and all but ignores the rest as Somebody Else’s Problem. It makes a dot, somewhere within what was previously a joined-up whole. And then someone else makes their own dot, and someone else carves out a space to claim to make their dot. But there’s nothing to link those dots together, to link between the dots – that’s the problem here.

When there’s nothing there to join the dots, complexity increases. Yet it seems that because specialisation is deemed to be ‘the way to get things done’, the only way to deal with that complexity is more specialisation – whereas in reality, specialisation is often more about avoiding complexity rather than managing it. Hence, as Atul Gawande warns in The Checklist Manifesto, we soon end up with hyperspecialisation – dots within dots, and then dots within dots within dots, onward seemingly to infinity. Fragmentation within fragmentation – and still nothing to hold it all together.

Same and different

Just to make things worse, this dotty game of specialisation pulls all of the attention towards the samenesses of the world – and hence drawing attention away from the equally-real differences.

Which is why we end up with the common delusion that most of the world consists of samenesses, or that it ‘should’ consist of nice, safe, sensible, predictable samenesses – when in reality it mostly doesn’t.

The core assumption here is that focussing on sameness is more productive, more efficient. Which, in a very specific sense, it is – as has been known and proven for a very long time, all the way back to the days of Adam Smith and his analysis of productivity in a pin-factory. Yet there are several very important caveats to that assumption – concerns that are all too often missed or ignored.

First of these, perhaps, is that ‘efficient’ is not the same as ‘effective’. We could summarise the difference by saying that efficient is ‘doing things right’, whereas effective is ‘doing the right things’, or, better, ‘doing the right things right’ – which is what we actually need. There’s perhaps nothing quite so pointless as striving hard to become more efficient at doing the wrong thing – and yet that’s what we’ll see happening in practice in almost any organisation or enterprise.

Next, it’s easy to string specialisms together when they’re closely related, such as in a single assembly-line in a pin-factory. Not so simple, though, when we must bridge between specialisms that have fundamentally-different or even conflicting terminology, methods and mental-models within the same nominal space – such as occurs these days in just about every organisation that’s much larger than a small start-up or a one-man band. Consider the different ‘worlds’ and worldviews of strategy, operations and accounting, for example; or the vast array of professional and technical disciplines across the entire scope of an oil-company, from exploration to exploitation to refinery and retail-sale.

And one of the more subtle problems that often arises in parallel with that over-focus on sameness is a delusion of ‘control’, of compliance to linear notions of causality, often typified by ‘business-rules’ and the like – when in reality the only true law, in business or elsewhere, is Murphy’s. (There’s no shortage of hard pragmatic proof – and scientific proof, too – that Murphy’s is so much of a law that it applies to everything, including itself: hence if Murphy’s Law can go wrong, it probably will. Which is why, most of the time, we get the comforting illusion that things are predictable and certain – yet also occasional firm reminders that they’re not…)

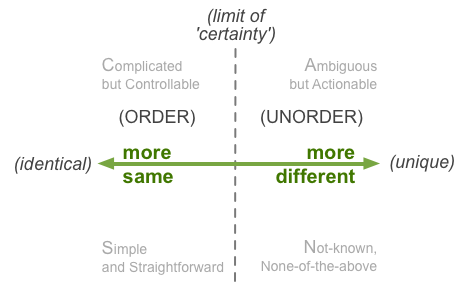

We can map this out along a spectrum of ‘same’ to ‘different’, or perfectly-repeatable to perfectly-unique. Over towards the left (‘repeatable’) side of that axis, doing the same thing gives the same results – or, more accurately, doing what seems like the same thing, but actually can encompass quite a bit of variance. Yet somewhere along that axis there’s a kind of dynamic-boundary or ‘limit of certainty’, beyond which doing the same thing leads to different results – or, alternatively, we have to do significantly different things to arrive at the same nominal results. And the further beyond that boundary we go, towards true uniqueness, the less predictable the results will be – a world not of order but ‘unorder’, to use Cynthia Kurtz’s term. We can summarise this visually as follows:

Specialism’s focus on ‘sameness’ tends to create an inability to handle uniqueness – or, in too many cases, there’s a tendency to hide from unorder in the spurious ‘certainty’ of an artificial notion of order. In this sense, just about every organisation and context is fragmented, shattered, into arbitrary silos, arbitrary fiefdoms, arbitrary dots: an incomplete, uneven splatter of dots, like a child’s spray-painting on the school-room wall. Often there are great gaps in the picture, great glaring gaps of Somebody Else’s Problem that end up being No-One’s Responsibility – or, more accurately, Responsibility That Everyone’s Evading. Which is why a typical customer-journey that tackles any real-world need – a simple health-check, for example – can easily become a tortuous traverse across a tangled confusion of misconnected, disconnected, disjointed non-’services’, creating frustration, waste and worse for everyone at every step. Not a good idea…

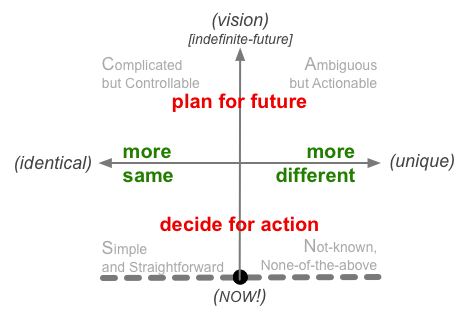

Just to make things even worse again, there’s a further complication that arises directly from the dominant management-model of the past century: ‘scientific management’, or Taylorism. In traditional skilled-work, the specialist does cover the whole range from same to different, and from abstract-theory to detailed-practice. But in Taylorism these are distinct roles: managers and analysts do all of the theory and the planning, whilst ‘the workers’ do all of the doing – and no-one crosses the boundaries between those roles. The workers’ job is solely to follow the rules set by the managers, with no deviation or variance allowed: if variance is needed, the manager does the analysis, and decides what the workers should then do. We can summarise this visually as follows:

However, there are (at least) two important catches with this Taylorist model. One is that it’s massively demotivating for ‘the workers’, and in practice most people are not all that good at solely following someone-else’s rules – hence management’s half-century obsession with the promise of IT, as something that in principle can exactly follow rules, and at far higher speed than any human, too.

But that’s where we hit the second catch, because although IT-systems can’t answer back, in general they also can’t think for themselves. If the rules don’t fit with what’s actually happening at run-time, everything has to stop whilst some analyst or manager can work out what to do. And that doesn’t happen at the same speed as the IT-systems – far from it, in fact… If variance happens faster than the analysts can keep up with it, the whole system can grind to a halt, or, worse, drift so far out of sync that it applies the wrong decision to each given context – a painfully literal example of ‘efficient’ being the exact opposite of ‘effective’.

When we put those two dimensions together, we end up with a ‘context-space map’ that describes the real world as a continuum of same and different, intent and action:

To make sense within that world, decide within that world, and act within that world, we first need to acknowledge that it is a continuum – a dynamic continuum – and be aware at each moment where we are and where we’re moving towards within that overall context-space.

Yet in most management-models, and especially in Taylorism and its present-day successors (‘business-process reengineering’ and the like), almost all of the attention is constrained up in the top-left corner of the frame – and the real-world is somehow deemed to be ‘wrong’ if it fails to conform to those expectations. And that top-left corner is further fragmented into individual specialisms, each one compartmentalised and distinct from every other, and each one purporting to hold ‘the truth’ about that aspect of the world – or even of the world as a whole. Any sense of continuity of the whole – that everything is connected to everything else, and depends on everything else – is all but completely lost.

Digital and analogue

The continuum is broken the moment someone places an arbitrary dot in that context-space, and says “This is mine! This is the truth!” Any form of specialism – and especially specialism without a solid generalism to link it always with everything else – places at risk the analogue continuity of the real world, breaking it up into digital fragments with no inherent continuity at all. Overly-simplified digital dots, needing to fake up an illusion of continuity between them that isn’t actually there.

When we talk about ‘joining the dots’, what we most often imply is some kind of pathway that links between various specialisms: a ‘customer journey’, for example. Yet even that may miss the point, because a predefined pathway is itself a kind of specialism, a linear dot, constrained and separated from an infinity of other alternatives.

To make sense of this, we need to think in analogue, not digital, terms. A world of specialisms is digital-like, one in which there are explicit boundaries everywhere, sharp cut-offs, distinct point-to-point connections from one to another. But the real-world is analogue: everything blurs more or less into everything else, and any sharp-edges between domains are mostly those that we choose to perceive and place there – and that may not ‘exist’ as such other than in our own imagination.

As with anything else digital, we need to remember that specialism is only an approximation of the real world, according to the arbitrary assumptions and constraints of some predefined model. It’s a useful abstraction, a useful simplification, that when used appropriately can help us work more quickly and more easily. Yet it’s an abstraction that’s far too easily abused: if we ever forget that it is only a smoothed-out approximation of a more analogue world, the risk becomes very real that we’ll trip over some hidden bump of inherent-uncertainty that’s been glossed-over by the arbitrary assumptions of that approximation. Again, not a good idea…

A question of dominance

Every enterprise is a system – an ‘ecosystem with purpose’ – constrained mainly by its core vision, values and other drivers. Within that system, everything ultimately connects with everything else, and depends on everything else: if it’s in the system, it’s part of the system, and, by definition, the system can’t operate without it.

Which in turn implies that no part of the system is inherently ‘more important’ than any other: every part is needed if the enterprise is to survive and thrive.

Which leads, in turn, to a direct clash with another commonly-held belief about specialisation: that some roles or specialisms are inherently ‘more important’ than others.

To take a simple medical example, a commonly-held assumption is that those who describe themselves as ‘specialists’ – the surgeon, the anaesthetist, the physician – are far more important than the ‘lowly’ nurses, technicians, janitors and clerical staff. Yet from the patient’s perspective, all of those skills and specialisms are needed – because without all of them in place, each acting in concert with each other at the appropriate times, the patient’s health will be at risk.

In a viable system, the ‘most important’ skill is the one that’s being applied right now, within each and every moment. In other words, ‘most important’ is contextual, and highly dynamic, changing with the immediate needs at each moment.

That kind of smooth dynamic transition from one specialism to the next is what happens in natural systems, in order to maintain maximum viability and maximum overall efficiency. But in enterprises and other human systems, what tends to happen instead is that – people being people – there are endless ‘status-games’ to try to cling to that status of ‘most important’, even where it does not and must not apply. The result is huge adverse impacts on efficiency and effectiveness – and, all too often, on viability as well.

Some of these dysfunctions are built into the very structure of our organisations: the feudal-style relationships implicit in the everyday org-chart, for example, or the Taylorist notion that managers are inherently superior to and more important than ‘mere workers’, even though the managers themselves don’t deliver any of the organisation’s tangible value at all. We also see this in notions such as ‘business/IT-alignment’ – which is more important? which side should take priority, such that others should align to it? – and also in all those board-level fights about which department is more important than all the others.

But what happens if one side – one specialism – does ‘win’ in these dominance-games? The answer is that it always leads to ineffectiveness across the enterprise as a whole.

For a simple illustration of this, imagine the organisation as comprised of five departments, based on a continuous version of Bruce Tuckman’s classic ‘Group Dynamics’ project-lifecycle: forming, storming, norming, and so on. Each department has its own role, and its own time-perspective. And the organisation as a whole depends on all of those departments, cooperating, passing on the baton of ‘most important’ from one to the next in the appropriate sequence. In real-life, of course, all of this is iterative and recursive, and has many other layers of complication and complexity, but for this purpose a simple overview should suffice:

So what happens if one of these departments clings to the idea that it alone is always ‘the most important’ in the whole enterprise? The effect is much like a wheel that’s badly out of balance: it’ll keep pulling forward at some points, backward at others, and, without sufficient force to keep it going, will eventually come to a halt, unable to move onward at all: wasteful, inefficient, ineffective, and frustrating for everyone. (Sounds all too familiar, yes?)

For each of these five ‘departments’, we can summarise what happens when it becomes over-dominant:

- Purpose: ‘idea-hamsters’ where nothing gets properly started – let alone finished – before the next idea hits (common in research-units and some startups)

- People: over-focus on ‘people-issues’, skills, safety, and over-sized egos (common in social-work contexts, NGOs and politics)

- Preparation: stuck in ‘analysis-paralysis’, always searching for the perfect plan (common in project-oriented organisations)

- Process: an obsession with speed and volume, regardless of quality, need or purpose (common in manufacturing contexts)

- Performance: bureaucracy, blame, and past-focussed pseudo-strategy such as ‘last year + 10%’ (at present, common in almost every type of organisation)

A more localised version of that ‘unbalanced wheel’ effect occurs whenever any specialism becomes over-dominant in any context. Overall, it’s probably one of the most common causes of organisational inefficiency and ineffectiveness, yet also one of the least-acknowledged – in part because of the huge political upsets that occur whenever we try to address it…

Which is where enterprise-architecture comes into this picture.

Into architecture

In principle, enterprise-architecture’s whole reason to exist is to help in joining the dots, helping the organisation work more effectively as a unified whole. We encourage people to find the right balance between same and different – between global effectiveness and local efficiency, between the need for standardisation and appropriate support those inevitable and necessary special-cases. We’re generalists, bridging across the silos, disciplines and domains: we act as translators, facilitators, helping people within the organisation and beyond to understand each others’ needs, and help each other to find and deliver the most appropriate solution for each need within the context of the whole. Things work better when they work together, on purpose: that’s perhaps our most useful guideline in this.

For enterprise-architecture, the tendencies toward specialism would be something that we would need to actively manage. And that can be a real challenge, not least because we’re not exactly immune from the same tendencies ourselves: as a discipline, enterprise-architecture still struggles with a strong tendency towards IT-centrism, and right now there’s somewhat of a tendency towards business-centrism that we also need to guard against. What we perhaps need to remind ourselves at all times is this: in a viable and effective enterprise, everywhere and nowhere is ‘the centre’, all at the same time.

Yes, specialisation is useful: it does help to get things done, within each distinct task and domain. No doubt about that at all. Not so helpful, though, when it ends up fragmenting everything into a near-unusable, near-unworkable mess…

In enterprise-architectures and in our everyday lives, we expend vast amounts of effort trying to re-join the dots, to make it possible to make some kind of practical sense of the whole-as-whole. Yet the whole mess happens because our dysfunctional cultures so much urge people to go dotty – creating specialisms, and more specialisms, and yet more specialisms, in a futile attempt to hide from the inherent and inevitable uncertainties of the real world. The urgent need to join the dots arises only because of that relentless tendency towards dotting the joins.

Not helpful. Not helpful for anyone, or anything.

Surely we can do better than this?

References

Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto: How to get things right, New York: Metropolitan Books, 2009.

Tom Graves, SCAN: a framework for sensemaking and decision-making – the Tetradian weblogs, Colchester: Tetradian Books, 2012.

Tom Graves, The craft of knowledge-work, the role of theory and the challenge of scale, Tetradian weblog, 2013: http://weblog.tetradian.com/knowledge-work-craft-work-theory-scale/

Tom Graves, ‘No jobs for generalists’ – a summary, Tetradian weblog, 2012: http://weblog.tetradian.com/summary-no-jobs-for-generalists/

An earlier, shorter version of this article was previously published on the Tetradian weblog at http://weblog.tetradian.com/dotting-the-joins/ .

About the author

Tom Graves has been an independent researcher, writer and consultant for more than three decades, in business transformation, enterprise architecture and knowledge management. His clients in Europe, Australasia and the Americas cover a broad range of industries including banking, utilities, manufacturing, logistics, engineering, media, telecoms, research, defence and government. He has a special interest in architecture for non-IT-centric enterprises, and integration between IT-based and non-IT-based services.

Happy birthday. 🙂

Brilliant article, just one small comment:

If efficient is “doing things right” and effectiveness is “doing the right things” then my conclusion is that you want to do both. You want to be effective AND efficient to “do the right things right.”. I would not say that the last statement describes effective, I believe it describes having both in place.

Besides that I fear that I need to rethink some of my current approach which is clearly focussing on breaking big things into smaller peaces to make them shipable. And that thought should be (hopefully) part of my book…

Hope to see you soon again.

KR,

Kai

Stimulating thinking, as per what we have become accustomed to expect of you, Tom.

Two key thoughts prompted in reading this:

a) We need much more AND than OR – the digital world seems to have led us unconsciously into being far too binary – when the world is analog – a continuum of choices which are a mix of the two binary choices being suggested – so we are inevitably dotty and joiny!!

b) In line with Stephen Haeckel’s thinking, we face adaptive problems and technical problems – we are accustomed to dealing with technical problems, and still learning how to deal with adaptive problems – ones where we need to learn about the problem as part of understanding the problem and being able to design a response. This leads us into looking at the problem from different perspectives – the beginning of specialisation. The challenge is to realise that specialisations can be complementary and are not necessarily mutually exclusive. So, our generalisation helps us maintain balance and to integrate the different specialisation based perspectives.

Food for further thought!!

Great article.

The enterprise domain is getting complexer with every day.

To keep understanding this domain, we cut it up in controlable pieces. “Hapklare brokken” we call that in Dutch.

But with the first cut, you create 2 subdomains, and an interface.

The subdomains are handled well, but we often forget the interface.

So my conclusion is, by cutting up a domain, it gets even more complex, but better understandable for humans.

It’s Yin and Yang, a complexity balancing act.

Thanks, Johan – and yes, a very good and important point there about “The subdomains are handled well, but we often forget the interface.”