Let it go

Let it go? Actually, I can’t. Or won’t. Or don’t know how. Or maybe it won’t let me go…

Something, anyway…

Right now I’m in the somewhat embarrassing position of being hooked on a Disney movie. Or, to be precise, one song in a Disney movie: Idina Menzel‘s rendition of Kristen and Robert Lopez’s Oscar-winning ‘Let It Go‘ , from the animated-film Frozen.

Okay, I have one perhaps rather-thin excuse: it’s safe enough to admit that I’m something of an animation-buff – I enthuse over Hayao Miyazaki‘s backgrounds and storylines, for example, or explore all the available information on Pixar’s work-culture with something of an enterprise-architect’s eye. So to me this Disney clip is stunning from several technical dimensions: the animation of Elsa’s breathing, synchronised to the singer’s inbreath – visible especially in some of the earlier parts of the song – the flow and movement of the fabrics, and the tiny flashes of reflection from snow-crystals as the camera-view swings round, all indicate just how complex the underlying digital-models really must be. The virtual-camera cinematography is frankly amazing, switching back-and-forth from a high very-long-shot at the start, to mid-shot, close-up, detail-shot, focus on other items entirely, detail-shot, high long-shot, mid-shot, and finally a huge swoop out to very-long-shot, and snap-cut back to close-up right at the end – I don’t think I’ve seen anything like it, even in any live-action film (though Paul Greengrass’ direction in the Bourne films sometimes comes close). And the backgrounds? – truly epic in scale, so much so that, with all of the snow-detail as well, I’m not at all surprised to read somewhere that some of the individual frames each took almost a week to render.

Yet it’s the lyrics of the song – and perhaps especially Idina Menzel’s rendition of them – that dig in the deepest, and keep me coming back to watching it again and again.

‘Let It Go’ is now often tagged as something of a ‘teen-anthem’, especially for teenage girls. Yet what it describes is much more universal: the way in which almost all of us end up hiding our real gifts, and, as the (mis)quotation from Henry Thoreau puts it, “go to the grave with the song still in them”. The real tragedy, as philosopher Umair Haque puts it, is that “most people don’t become themselves [because] they are busy desperately pretending to be most people” – because that so often seems to be the only safe thing to do.

Which is where this kinda links in with the theme of ‘embracing our inner-weirdness‘, as in some of the recent posts here. Everyone is different, and everyone has their own special gifts, their real gift to the world – part of the make up of their ‘wyrd’, almost whether they like it or not. But in cultures and contexts that seemingly demand conformity from us – especially conformity to others’ supposed ‘needs’ to avoid their own issues – many (most?) of us end up suppressing those gifts within us, solely to keep others happy and ourselves seemingly safe from further attack.

To give a very personal example, one of my – well, I suppose I’d have to call it a ‘gift’, though way too often it feels more like a curse – is that, right from earliest childhood, I seem to see things differently from almost anyone else. I see things in terms of systems, in terms of wholes: I can’t help but see the huge limitations of single-thread thinking, and the damage that it causes. Living in a culture that all but demands single-thread thinking, and that blames everyone else for the consequences, that’s been kinda difficult… – especially when the most common response to any even-unintentional message from Reality Department is the age-old game of ‘shoot the messenger’… Being able to look sideways on at the world is a very useful trait for an Outsider consultant: but most people have no idea how much I have to hide of what I really see – and the endless inner struggle to keep myself from blurting it out…

So yeah, this clip hit on more than a few sore-points, all right…

(Before going any further, the Regrettably-Necessary Legal Bit: “Copyright Disclaimer: All rights to the movie, images, songs and lyrics of ‘Frozen’ belong to Disney Corporation. Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for ‘fair use’ for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research.” ‘Fair-use’ of copyright-materials is asserted here for purposes of comment, teaching and research.)

Compared to the simplistic black-and-white worldview of so many family-films, the storyline for Frozen is unusual in that there’s no main ‘villain’ as such: instead, the core conflict is between two people each trying to do the right thing, yet in doing so – until the end – only making things worse for each other, themselves, and everyone else. Hence it’s probably best to describe the background for this clip with the minimum of ‘spoilers’.

The character we see in this point in the film is Elsa. She’s a princess (c’mon, it’s a Disney family-movie, so she must be a princess…) – or, more precisely, it’s actually her coronation-day as queen. The lead-up to this clip – which starts at around the 30-minute mark in the full movie – is that Elsa was born with the ability to conjure up frost and snow, and shape it: but as a young child, she almost killed someone when a happy game went badly wrong, and she’s had to hide her ‘gift’ ever since. Yet just after the coronation, the metaphoric cat is let out of the bag – or glove, to be more precise, which is why a glove is missing when we first see her – and she runs away, to try to avoid hurting anyone else.

When we first see her, in this clip, she’s a tiny, tiny dot, trudging alone up a steep snow-covered mountain-slope:

The snow glows white on the mountain tonight,

not a footprint to be seen.

A kingdom of isolation

and it looks like I’m the queen.

Yeah, that one’s very familiar… In my own case, I’ve taken on the role of the Outsider for pretty much the whole of life – even within my nominal birth-family, let alone anywhere or anywhen else. I’ve never had the sense of ‘fitting in’ at any place, social and/or geographic: not any organisation, certainly. The role of the Outsider is extremely important to organisations, because that literal eccentricity – ‘offset from the centre’ – is often the only means to provide enough leverage for real change. Valuable to the organisation, that is, but often at huge cost to the Outsider – of which that sense of isolation is merely one of the more minor challenges.

The wind is howling like this swirling storm inside.

Couldn’t keep it in, Heaven knows I tried.

“Couldn’t keep it in, Heaven knows I tried” – yeah, that one’s very familiar too: the Outsider is never supposed to show who they are, that they see or think or act differently from anyone else. The problem is that in my case, for example, that sideways-view slips out without warning: can’t help it, it’s how I see, it’s who I am. Sorry. I can’t not-see what I see, just because others are uncomfortable about what I see – I do try as hard as I can, but Reality Department just doesn’t work that way. Sorry. I seem to spend a lot of time saying ‘Sorry’, apologising for who I am…

But “this swirling storm inside”? – not really. Not now. Not after this many years of holding back, holding down. Not even enough energy left for a ‘swirling storm’. More a numbness, a nothingness, more like. A lot worse than a ‘swirling storm’, in many ways…

Don’t let them in, don’t let them see.

Be the good girl you always have to be.

“Be the good girl you always have to be” – yeah, that sense of the ’embodied parent’, that endless, relentless self-criticism, self-control, intense self-blame at any and every slip, every ‘mistake’, every momentary self-exposure of who we really are. So well illustrated by this frame of Elsa, from the song-clip:

( (c) Disney 2013)

Definitely not solely a “good girl” matter, by the way – not at all. Not when my now elderly mother still uses that demeaning phrase “there’s a good little chap” whenever my now sixty-plus self silences himself for her benefit. Not when almost every self-styled boss enforces self-silencing on her staff in much the same way…

Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know.

This is the real crux of it: silencing ourselves, hiding ourselves, hiding who we are. Hiding our real gifts, our real power. Always. But why? And for whose benefit? That’s the question that doesn’t get asked – and that we need to ask…

Descartes got it wrong: it isn’t “I think, therefore I am”, it’s “I feel, therefore I am”. We have some choice about our thoughts: we have no choice whatsoever about what we feel, and when we feel it. (We have choice about how we respond to what we feel, but not about the feelings themselves – a perhaps-subtle yet very important distinction!)

I cannot count the number of times someone – some woman, usually – has insisted some variant of “You can’t feel that! You don’t feel that! You shouldn’t feel that! You have no right to feel that!” (Followed, all too often, by a mocking accusation that “Men are such unfeeling brutes”…) But the blunt fact is that I can feel that, and I do feel that – that whatever-it-is that they don’t want me to feel – and it’s not that I ‘should’ or ‘shouldn’t’ feel it, or have ‘a right’ or ‘no right’ to feel it, but simply that I do feel it, whether I want to or not.

If “I feel, therefore I am” is true, then the more we suppress and deny what we feel – especially when such suppression is solely for others’ benefit, others’ comfort, so that they can avoid the real-world requirement to feel what they probably, uh, should feel… – well, that’s when things get into a mess. That’s when, in an all too literal sense, we learn to cease to exist as ‘we’, as ‘I’ – leaving only a hollow shell, or, as in this song, a “swirling storm inside”.

But “conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know” – yeah, that’s very familiar. More like a way of life, really. Or non-life…

At this point in the song – and perhaps unlike most of us, most of the time – Elsa somehow finds a way to end the self-blame, and finally ‘let it go’:

Well, now they know!

Let it go, let it go!

Can’t hold it back any more.

Let it go, let it go!

Turn away and slam the door.

It’s really noticeable how much she lights up – in a quite literal sense, in the film – as she lets go and allows her power and her gifts to begin to be expressed. Same is probably true for all of us, really: I’ve certainly seen it very often when someone to whom I’ve been teaching a new skill suddenly ‘gets it’, and finds their own power within the skill – they really do ‘light up’, in an emotional sense at least.

I don’t care what they’re going to say.

Let the storm rage on.

The cold never bothered me anyway.

“I don’t care what they’re going to say” is easy enough to say when there’s no-one else around – which is why so many of us crave to be alone, for some space to ‘be ourselves’ that isn’t full of this ceaseless sense of being attacked for simply being who we are. Not so easy in the real-world, unfortunately… In my own case, for example, the fact that I do care about what others say and feel, and do aim as much as practicable to respect others’ self and story, makes me a very easy target for those who don’t. Not fun…

But if we can get past that, then yes, it does seem more possible to acknowledge who we really are – if only to ourselves – somewhat as Elsa does here. As she says – or sings, if you prefer – the real key is our own self-generated fear, and somehow breaking free from that, if only for a short while:

It’s funny how some distance,

makes everything seem small.

And the fears that once controlled me, can’t get to me at all

It’s time to see what I can do,

to test the limits and break through.

Where it gets tricky is in the kind of assertion that we see in the next couple of lines:

No right, no wrong, no rules for me.

I’m free!

Lovely idea: ultimately it’s essential to all innovation, it’s something almost all of us would desire, and it’s a foundation-stone of several political models such as US ‘Libertarianism’. But there’s a lethal catch: and if we don’t respect that catch, and learn how to work with it, it’ll come back to bite us – hard. Which is where so many of these problems arise in the first place.

What we’re actually talking about here is anarchy, in its literal sense of ‘without rules’. Yet the key, and the trap, is that there are two fundamentally-different – in fact diametrically-opposed – forms of anarchy: and only one of them works well in the real-world. The one that works – the form that we might describe as ‘real anarchy’ – is when we accept wholeness responsibility: if we break ‘the rules’, we also fully accept all of the consequences of doing so. The dysfunctional form – one we might describe as ‘kiddies’ anarchy’, because it’s very much the mindset of a self-centred two-year-old – is when we demand that no rules should apply to us, that we must have absolute ‘freedom’ to do whatever we want, yet also insist that our rules ‘must’ apply to everyone else: heard in real-world absurdities such as “all property must be liberated, but don’t you dare touch my stuff!”. If we demand ‘freedom’, we need to be really clear as to which of those two forms of anarchy we’re calling on: because if we go too far into ‘kiddies’-anarchy’, well, that’s when all hell can break loose. Literally, sometimes. Not a good idea…

So yes, we do need to remember that, relative to the real world, Elsa’s transition here is something of a fairy-story – but a fun one to watch, as she fully claims her real power, her real gift, and, with evident exuberance, really does ‘let it go’:

Let it go, let it go.

I am one with the wind and sky.

Let it go, let it go.

You’ll never see me cry.

Here I’ll stand, and here I’ll stay.

Let the storm rage on.

At this point in the film-clip, she creates a vast, soaring palace out of nothing but thin-air, snow and ice.

(Completely unreal, you might think: but I’m not joking when I say that I once knew a young woman – one of my graphic-design students, in fact – who really was capable of doing at least the first stages of a real-world version of this. In a life that’s been filled with a lot of oddities and strange experiences, this was the one indisputable example of intentional-psychokinesis that I’ve seen first-hand: watching her ‘let it go’ in her own way, in the midst of a casual conversation with friends – with the light-fittings ten feet above our heads swinging around on their chains in any direction she chose – was frankly scary, though for her it was just a routine part of her everyday life. Yet I’m also not joking, though sadly not all that surprised, that I’d subsequently heard that she’d died – suicide, apparently – only a year or two later: it’s very hard to survive the scale of attack that arises from most others when we bend their ‘reality’ that far from the norm… As a kind of tribute to her, the character Jeni in my sort-of-novel Yabbies is based directly on that young woman.)

My power flurries through the air into the ground.

My soul is spiraling in frozen fractals all around

And one thought crystallizes like an icy blast

I’m never going back; the past is in the past!

“The past is in the past”: that’s another phrase here that, like “I don’t care what they’re going to say”, tends in the real-world to sit more in the wishful-thinking area than within any experienceable reality. It’s a nice idea, a nice ideal, that notion that we could just walk away from all of our past and never have to face any of it ever again: but in reality – and as Elsa discovers to her cost later in the film – the past has this nasty habit of coming back to haunt us anyway, usually when we’re least equipped to cope with it… And if that concept of ‘the threads of wyrd’ is correct – as summarised briefly in the ‘inner weirdness‘ post, and in much more depth in my old books Positively Wyrd and Wyrd Allies – then there’s no possible way to avoid the past: it’s always with us, and has always been with us, right from the start. The trick, then, is to learn how to work with it, rather than trying to run away from it.

And it’s in the final chorus and final verse below that Elsa really lets rip, and completes her transformation to the Snow Queen.

(Okay, there’s a lot of magical-fantasy in this particular story-type transformation, but some of the real-world changes I’ve seen have been almost as dramatic. Perhaps the most striking example was a fellow graphics-student from a couple of years behind me at Hornsey, a guy called Stuart Goddard, who over a single weekend transformed himself into a completely different persona, as Adam Ant – his voice, posture, mannerisms, gesture, demeanour, even the shape of his face, all so wholly different as to be almost unrecognisable. Weird indeed…)

Let it go, let it go.

And I’ll rise like the break of dawn.

Let it go, let it go

That perfect girl is gone

Here I stand, in the light of day.

Let the storm rage on!

The cold never bothered me anyway…

That’s the end of the film-clip, and that specific song: Elsa’s transition and transformation, at last coming out of hiding, to ‘let it go’ and claim her real power.

Yet in reality – for her, and for us too – that’s only the first part (and, for us, often the easiest part) of that story: even for Elsa, real-life ain’t that simple… (such as when younger sister Anna turns up, wanting to help… ). It’s probably not too much of a spoiler to say that a core theme of the rest of the film is that Elsa has to find her way back to the everyday world again, yet without abandoning her power, without hurting anyone through using her gifts, and without abandoning herself back to her old fears once more.

Even though it’s only one part of the whole story, ‘Let It Go’ is a remarkably powerful marker and talisman for that first-stage transition. That it affects a lot of people in that way can be seen often in the comments-section on that Disney YouTube page. Most poignant, perhaps, was one guy who said that “As a ‘big manly 20 something man’ who plays kickass FPS’s and head bangs to rock n roll… this song made me cry” – and continued:

As someone with a form of Autism called Asperger’s Syndrome, who has difficulty being in crowds, and socializing with people without offending them or seeming “odd”. This song spoke to me on such a deep level, I would love nothing more than to be like Elsa. To hide away, be alone, yet live free from that social fear or pressure. I watched this song with tears in my eyes saying “that’s me.”

But this movie also showed me that I couldn’t live like that, that even though I think being alone would be the best thing for me, it would be the absolute worst thing the those who love me.

So I just want to say, thank you Disney. For showing me that I don’t have to “conceal, don’t feel” that I can “Let it Go” but not be alone in order to do that.

So yeah: not just fiction, then. The story and the song may be fiction, but the issues that it addresses are very much part of most people’s lives.

Which, given that the main focus of this blog is around enterprise-architectures and the like, is where we need to bring this back to the practical and the everyday…

Implications for enterprise-architecture

Let’s start off by making this personal:

— What would you say are your unique ‘gifts’? – those aspects of yourself that make you you?

— For which of those gifts and skills would you find yourself saying to yourself some variant of “Don’t let them in, don’t let them see / Be the good [you] you always have to be”, or “Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know”?

— For each of those, why? What are you afraid of? Or, perhaps, what are others afraid of, leading to responses from them that you’re afraid of?

— How much energy and effort does it take to maintain that mask of ‘Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know’?

— If you do manage to maintain the mask of ‘Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know’, what happens to your sense of self? Do you still feel as though you are you, whilst pretending to yourself and others that some aspects of ‘you’ don’t actually exist?

— If you don’t manage to maintain the mask of ‘Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know’, what happens? What are you afraid would happen?

— In what contexts is it safe to ‘Let it go’? In what contexts is it not safe to ‘Let it go’? What’s the difference? – with whom, or what, where, when, why? What are the sources of those differences?

— And what support – if any – is there for you to ‘Let it go’, especially in a way that not only supports you, but also some broader overall aim or purpose shared with others? Where does that happen? – with whom, how, when, why?

— How do you feel, on those perhaps-rare times when you do ‘Let it go’? What’s the difference?

— Perhaps in particular, is it safe – or not-safe – to ‘Let it go’ in a ‘work’-type context? What would happen if you did? What happens when you do?

— And, at work and elsewhere, what are you, your family or friends, your colleagues and co-workers, and your company or corporation, all missing out on because of that seemingly-necessary mask of ‘Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know’? How much is lost, not just to you but to the world as a whole, because you feel or believe that you ‘must’ hold back from expressing and enacting those natural ‘gifts’ that are an inherent part of who you are?

Kinda scary, yes? Also sad, how much is truly lost…

At which point, we really do need to ask why… because everyone loses from this.

So, let’s take it up a couple of notches. Look around at home, at work, on the street – and realise that almost everyone you see has exactly the same struggle as you about this. Almost everyone is stuck in some variant of ‘Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know’ – and the loss, the waste, is almost unbelievably huge. Everywhere around us – and in us too – perhaps most of the real power and joy in maybe most people’s lives, just lost, wasted, gone, replaced instead by relentless anxiety, repression, fear. What a waste…

Why?

Or, perhaps more to the point, what could we usefully do about it – perhaps especially within our own professional remit of enterprise-architectures and the like?

This is where it gets kinda tricky… yet very interesting, too.

The key problem is this. As the fictional Elsa shows in her own way in that story, our ‘gifts’ are powerful – and when we use them well, empowering – so we do need to support all of that. Yet as Elsa also shows, they can cause hurt, too; and as we’re learning how to use them, we’ll make ‘mistakes’ – that’s equally inevitable as well. So if we want things to work well, we need to design for all of those facts – not try to shut everything down so as to keep everyone ‘safe’.

What kind of hurt? Well, we can easily hurt ourselves: a gifted athlete still has to learn how to run, jump, swim, balance, without causing damage to their own body. And there’s a similar emotional hurt every time we fail, or fail to match up to our own expectations: yet if we can’t cope with the emotional hurt of failure, we’re not going to be able to get far in learning a new skill – which means that a ‘gift’ may simply languish for lack of use.

In much the same way, we can easily hurt others too, until we learn how to manage our ‘gifts’ well – the core of the story of Frozen revolves around exactly that, but there are many, many other instances in the everyday world, in sports and elsewhere.

But it’s the interactions with others – reactions from others – that really cause the most hurt, that are most likely to send us back into a downward spiral of “Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know’. For example, if we’re good at something, that’s quite likely to invoke jealousy or envy from others who aren’t – the classic ‘tall-poppy syndrome‘, as it’s known in Australia.

(It’s not just skills, either: some women, and some men too, evoke that kind of jealousy and envy just from the way they look. Not fun to have to live with, seemingly having to conceal who you are, just because of how you experience how others see you. Yet hence also, of course, the ways in which whole cultures impose on everyone their demands for some variant of ‘Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let it show’ – from the whole-body covering of a burqa, to the whole notion of ‘indecent exposure‘, and much, much more. Yeah, it’s tricky…)

In the business context, one of the most common sources for this kind of dysfunction is the notion of ‘the management-hierarchy’: the somewhat-bizarre notion that only certain people should have the ‘right’ and ‘authority’ to determine what ‘gifts’ are to be allowed and not-allowed, or used and not-used, within the workplace. We then combine that with an insane societal-scale economic-model, in which people are deemed to have the ‘right’ of access to shared societal resources only if they allow themselves to be entrapped in ‘making money’ for someone else – the mess most commonly described as ’employment’. And we combine yet it again with the notion that ‘the boss’ has the ‘right’ to hire and fire – in other words, arbitrarily include or exclude someone from meaningful work and/or access to societal-resources. We could hardly create a model more guaranteed to cause huge amounts of fear, or near-lethal interpersonal-dysfunctions, or suppress most people’s gifts and lives… And we then wonder why our organisations often don’t work very well, when in many cases it’s frankly amazing that any work gets done at all!

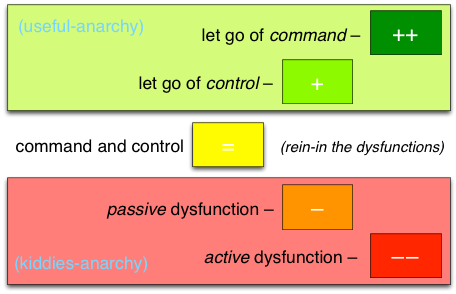

The one part that is valid within all of that mess is the risk of a descent into full-on kiddies’-anarchy. If everyone at work just ‘Let it go’ – or, at least, so runs the fear – then anarchy would result. And yes, kiddies’-anarchy is something we definitely need to avoid and dissuade as much as possible. Yet actually, a real-anarchy is what we’d want and need, if our organisations are to run at their maximum potential – because real-anarchy is where those ‘gifts’ gain their maximum exposure and maximum expression, ultimately for everyone’s benefit. We can summarise the difference via the SEMPER model of power and ‘response-ability’ in the workplace:

Most organisations still focus on imposing and maintaining command-and-control: the belief is that they need to do so, otherwise everything will end up collapsing into kiddies’-anarchy. Which it often does, as the active dysfunction of aggressive ‘putting others down’ and suchlike, precisely because they try so hard to suppress any possibility of ‘Let it go’. If the stress of an everywhere-enforced ‘Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let it show’ has nowhere else to go, it’ll implode into the organisation anyway.

The next level up from that, passive dysfunction, is the classic silo-mentality – “it’s not our problem, not our responsibility, nothing to do with us”. Everyone’s so held back in ‘Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let it show’ that often nothing happens – nothing at all – beyond the barest minimum.

By comparison with those, the classic command-and-control is actually an improvement. At least something happens – even if it’s not very much…

Yet to get an organisation to work well – to achieve its true potential – we somehow have to let go of command-and-control all over again.

The first part is to let go of control – stop forcing everyone to be the same. The simplest example of this is ergonomics – adapting equipment to match the person, rather than forcing the person to adapt to the equipment. But we really need a stronger acknowledgement of who those people are, as themselves: which means, for example, ‘hiring for attitude than aptitude’ – hiring as the whole-person, rather than as a ‘production-unit’ in accordance with some predefined ‘job-description’, in classic Taylorist style.

And finally, we let go of command: we actively encourage and support people into being able to ‘Let it go’, being the whole of who they are. In line with the research on motivation summarised in Dan Pink’s book Drive and suchlike, we need to actively support each individual’s sense of autonomy, mastery and purpose, and – to ensure that that doesn’t unintentionally collapse back into the kind of cacophony of random ‘Let it go’ that risks a collapse back to ‘kiddies’-anarchy’ – provide clear linkage for each of those individuals to connect to shared-purpose, a sense of belonging to ‘that which is greater than self’.

To help the organisation reach its true full potential, every person needs to be able to put every one of their gifts to full use. Which means that we need to provide conditions under which, somehow, everyone is fully set free from ‘Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let it show’ – including all the ways in which they would otherwise constrain themselves. And no, that kind of context isn’t easy either to create or to maintain… – but it really is the one thing that can make work itself always feel worthwhile, for everyone.

So, where is your organisation on that spectrum – from active-dysfunction, all the way through command-and-control, to a fully-shared ‘Let it go’? And, using what you’ve seen here, what can you do, within your enterprise-architectures, to help your organisation to lift its game?

—

Okay, okay, I know this has been a long one – even longer than most of my usually-already-too-long posts… But I hope it’s been of some use to you? Over to you for comments and suggestions, anyway.

Leave a Reply