Embracing our inner weirdness

Easter. In the Christian calendar at least – and in the pagan one that preceded it – it’s supposed to be a time of rebirth.

Yet rebirth of what? And into what, or whom?

If it’s a more personal form of ‘rebirth’, then who am I, really?

For that matter, who are you? Who is anyone, really? Who is anyone?

On the surface, the answer might seem really simple. For example, in my case, all I need do is look in a mirror, and see this guy:

Or, to be pedantic, that photo is from about seven years ago, but there’s not much difference to now: a bit less hair even than there, and what’s left is perhaps a bit greyer, but that’s about it. That’s who I am, you might say: one more small, somewhat-overweight, somewhat-sad-looking, somewhat late-middle-aged nothing-much of a nobody – yeah, that’s me, really. Just another face in the crowd.

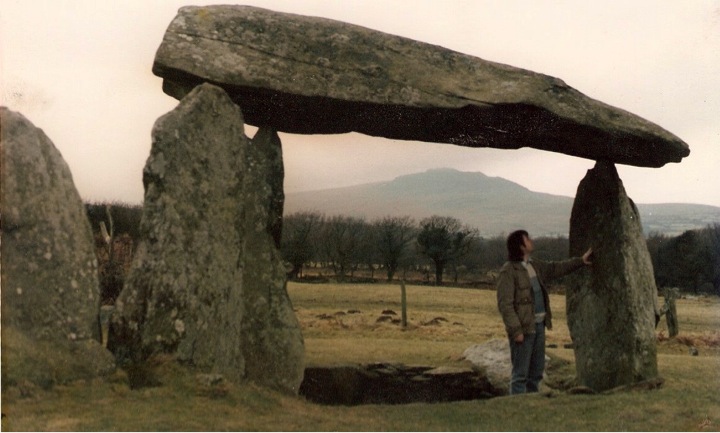

Yet in a way it’s always a shock to me, seeing that reflection in the mirror, because often – usually? – my own understanding and sense of ‘who I am’ can be very different. For example, there’s this guy, exploring an ancient stone structure at Pentre Ifan (I think?) in northwest Wales:

– who is also ‘me’, though some thirty or more years ago. Which, through me, is also now. Sort of. Kinda weird: not so much synchronicity – literally ‘at the same time’ – as more like ‘syntopicality’ or ‘synatomicity’, two different times in the same place or, here, all within the same one nominal person.

Which also means that the mindsets and experiences of those different times occur within the same person, too. Which, here, is me. Two mindsets at the same time – or close to the same time, anyway. And back then, as I’d mentioned in the recent ‘Republishing my other backlist‘ post, I’d been doing a lot of work on sensing in the landscape, making sense of the landscape. (Also a lot of code-development in assembly-language, for typesetting systems, but that in itself is another story. And learning the hard way how (not) to run a high-tech startup – though that’s yet another story too.)

So it was kind of interesting in the last week to be spending two days in Sweden with new prospective business-partners doing some fairly intensive enterprise-architecture work, and then straight away doing another two days back here in Britain at a very different conference with a very different crowd – a bunch of dowsers, in fact – going back to that landscape-oriented past. Yet in both cases the emphasis was about the need for discipline – something that seems to be skipped over far too often in both types of domains… So in a sense, although they’re different spaces, I can work with them in similar ways, and even bring elements of one into the other, each way: for example, what I learnt back then about sensing and sensemaking in a landscape is exactly what I use now in making sense of an entire organisation and enterprise. And that happens because those times and mindsets kinda connect through me. Whoever or whatever ‘me’ is…

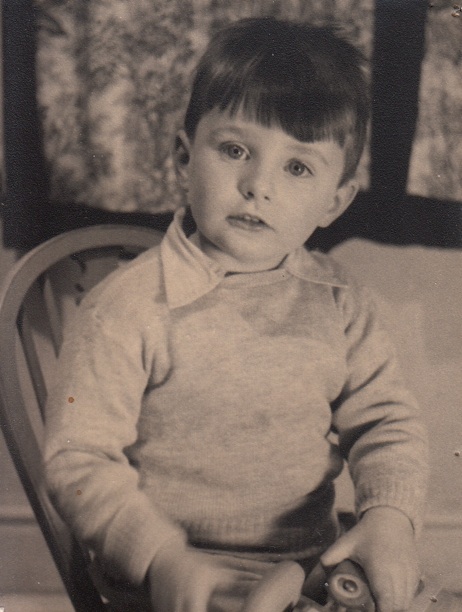

And then there’s this guy:

– who is also ‘me’, though more like sixty years ago. Which, through me, is also now. Sort of. Which is definitely kinda weird, when all those different times coincide…

And again, the mindset is different again – very different. Yet in some ways, oddly, also much the same. For example, probably my very first clear memory would have been from around then, riding on my tricycle outside my parents’ surgery. A small boy of about my age was with his mother, and referred to her as “Mummy”. “That can’t be right!”, I thought, “My mother is called ‘Mummy’!” Even back then, there’s the same focus on logic and structure there that I still have now; and although I’d obviously grasped the notion of names, and nominal uniqueness of names, I’d not yet understood the need for abstract or role-based naming – which I’d use intensively these days in enterprise-architectures, of course.

Even back then, I was acutely aware of being an Outsider, both within and relative to a family of Outsiders: an often painful and certainly lonely (non)-relationship that’s continued on right the way through my life, so much so that, for example, I’ve never yet been a salaried employee – always an independent, an Outsider. Yet professionally very useful, too, of course: few consultants will be able to do their role well unless they can find the Outsider within themselves – able to look sideways-on at any required context.

And there are other traits that have continued on from that time. One of them is a focus on fairness, on self-honesty, on responsibility as ‘response-ability’, on the importance of exploring, enquiring, of ‘run and find out’ – all of which come up again and again in my current work on power and responsibility in the workplace, on rethinking economics in responsibility-based form, and on ‘really-big-picture enterprise-architectures‘ and the like.

There’s a lot of really childlike qualities there, too – curiosity, interested in anything, things like that. Perhaps the most interesting, though, is an oddly practical belief in magic – in many different senses of the word. It came out again quite a lot in all that work on dowsing and landscapes, thirty and more years ago – the kind of thing that self-styled Skeptics hate, that they’d insist cannot possibly exist. Yet it also comes out again in my current work now, too, in again a very practical way: because how else could we describe invention, innovation? – after all, there too we do, in a very literal sense, create something from nothing. With a lot of hard work to make it fully happen, yes: but the exact same is true for every form of magic – to quote Arthur C Clarke, “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”, yet it’s equally true that “any sufficiently advanced form of magic is indistinguishable from technology”. And without that moment of magic, of ‘creating something from nothing’, there is no technology – a point that those who would seek to wipe out out all belief in magic do tend to forget…

All of which is also weird in a literal sense, too: ‘weird’ – or, to use a perhaps more-accurate spelling, ‘wyrd‘ – is the old Nordic/Anglo-Saxon version of fate, or destiny. (I wrote a couple of books on this back in 1990s, as it happens.) Kind of like Murphy’s Law on steroids, but also with a real twist, such that every thread, every possibility passes through everyone, all at the same time. There’s always a choice, but there’s always a twist; and wherever there’s a twist, there’s always a choice, a possibility.

Yet if every thread passes through everyone, and everything’s changing all the time, what then is ‘I’? “I am not that which changes – I am that which chooses” – that’s what I wrote back then, in those books, and it still seems valid now. But that’s not just in the abstract: the experience of that natural, inherent weirdness in all of us is something else again…

And it’s something I came across once more, in a binge of solo video-watching over Easter when I really needed to have been working on something else. Oh well. Yeah, it was quite a binge, though, and the choice of videos no doubt says a lot about me: a couple of somewhat bittersweet sci-fi-with-romantic-elements (‘Another Earth‘ and ‘Seeking A Friend For The End Of The World‘); an action-comedy (‘RED‘), a Terry Gilliam, of course (‘Dr Parnassus‘); a sort of grungy psychic/action-movie (‘Push‘); and a whole bunch of ‘family’ animations (Miyazaki’s ‘Arriety‘, Aardman’s ‘The Pirates‘, Bergeron’s ‘A Monster In Paris‘, the two ‘Despicable Me‘ movies, and Disney’s ‘Frozen‘).

All of them struck a chord in their own ways – that varying mix of sci-fi, character, relations, comedy, imagination, ‘the theatre of the absurd’, a sideways-on view of the world, a childlike (yet not childish) view of ‘the possible’. Yet perhaps, of all of those films, it was ‘Frozen‘ that struck me the most. Yes, it’s Disney, which means that yes, there’s yet another princess, and yes, yet another swathe of songs, some of them way too much over into the please-can-I-forgettable category. But one of the songs was very different: the stunningly-powerful (and Oscar-winning) ‘Let It Go‘, by Idina Menzel (scene 5, around 29:40 to 33:20 in the UK release of the film). Even musically it’s extraordinary, starting off with quiet poignant sadness, then breaking free, building upward in volume and power to a stunning climax, and a sudden final counterpoint-contrast last line. Yet it’s also about the step-change for character Elsa, breaking free from her deeply-ingrained self-doubt and self-blame, and at last claiming the real power of her own inner weirdness. Never mind that, a couple of scenes later, she’s pretty much back in the same self-doubt and fear again: it all gets resolved in the end, anyway. The real point is about claiming one’s own weirdness: acknowledging and embracing all of the strands in her make-up, her character, her story – acknowledging her wyrd, as the Nordic view would say.

One of the reasons that song struck home so hard is that that’s a struggle I’ve always had: acknowledging and embracing all of who I am, rather than surfacing just the current ‘publicly acceptable’ aspects and trying – often unsuccessfully – to hide everything else. Reality is that, yeah, I’m complicated, complex, often just plain weird: and whenever I’m engaged in anything, that weird (or wyrd?) interweaving of the whole is always there. It has its disadvantages at times, of course, yet many real advantages, too: for example, I wouldn’t be able to do the deep-exploration work that I do in enterprise-architectures and the like if I didn’t have that layered weirdness echoing back and forth within me.

Yet that’s true for all of us: that’s the whole point here. We’re not machines, programmed to do only one task at a time: in everything we do, we each bring all of ourselves into the story, whether or not we’d intend to do so. And it might be a lot more helpful all round if we each did rather more of acknowledging and embracing and being honest about our own inner weirdness, too…

Which, in turn, brings us – perhaps inevitably here? – to the everyday practice of enterprise-architectures and the like. To put it at its simplest, if people are inherently weird, then it might be wise to build our enterprise-architectures to reflect that fact? – rather than trying to force them to each be some kind of not-very-functional machine, which still happens far too often, especially where the sad delusions of Taylorism and IT-centrism still hold sway. It’s not just that each person bring each and all of their own times and experiences and expectations to every task: collectively, we have shared-access to all of those, all at once, whenever we need them – if only we’d acknowledge that fact. And by definition, an enterprise is always about people, with machines never much more than an afterthought, an enabler: hence might it not be wiser to start with people first, rather than the machines?

And if we’re going to start with people, then it might also be wise to start from who we are – who we really are, in all of our weirdness.

So yeah, it might sound kinda weird, but that suggests that a kind of rebirth really is more than overdue here: and that within that rebirth of enterprise, and ‘the enterprise’, embracing our inner weirdness might well be a wise way to go.

Tom, Your best post on EA ever.

I’m very fond of this quote:

“Getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It is getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That is how we know we are alive: we’re wrong.”

— Philip Roth “American Pastoral” via the book “Being Wrong”

I include myself in the term “people”. So living is not only about getting others wrong; it’s about getting myself wrong again and again and again. And arguably the major cause of getting myself wrong is ignoring or suppressing my own inner weirdness. In recent years, my primary measure of my maturity is my degree of comfort with my own weirdness. I still have a long way to go.

So maybe EA needs to start by helping organizations open up about their weirdness and going from there; instead of trying to “normalize” itself using frameworks, etc. Maybe EA should be more like the kind of city planning some cities like Austin, TX, and Santa Barbara practice with their “keep our city weird” campaigns.

Nick – many, many thanks for this reply above! It felt a seriously risky post, yet one that also felt important to do: I’m really, really glad that is made some degree of sense to one person at least! 🙂

@Nick: “And arguably the major cause of getting myself wrong is ignoring or suppressing my own inner weirdness.”

Yes, exactly.

@Nick: “In recent years, my primary measure of my maturity is my degree of comfort with my own weirdness. I still have a long way to go.”

Again, brilliant – just brilliant… (And yes, “I still have a long way to go” definitely applies to me too… 😐 )

@Nick: “So maybe EA needs to start by helping organizations open up about their weirdness and going from there; instead of trying to “normalize” itself using frameworks, etc.”

Yes, exactly (again! 🙂 ). There’s obviously some balance required here – frameworks and the like do have very real value, if only for interoperability and so on – but remembering to include all of the weirdness, the uniqueness, the ‘particularity’ and ‘local-distinctiveness’ (to quote UK landscape-charity Common Ground) is really important too.

Once again, many, many thanks for this!

Glad you liked my comment. I’ll add one other insight on how I deal with “getting myself”, which again, can apply to organizations as well. It’s how I deal with my different selves over time (ps the word you may be looking for is “diachronic”).

My basic approach is to consider my different selves to be akin to my “ancestors” just like my parents and grandparents, etc. To put it in stark terms, I act on the belief that for all intents and purposes, my 8 year old self is dead. I am his descendent, but I am not him. How could I be? He had a very different world view than me–that of an eight year old. I have memories of him–vivid ones even. But I am not him.

I’m also not my college-age self or my mid-thirties self. I believe that every 10-20 years, I effectively become a new person (rebirth). It may slow down as I age. I’m not sure yet.

In my twenties and thirties, I came to this way of viewing my past selves as a way of coping with my grief over no longer being the boy I once was. Rather than continue to feel bad that my present self did not embody completely my past self, I accepted that I was in a sense “reborn” as a new self every decade or so.

This perspective helps me in a number of ways: (1) I don’t fear death because I feel as if I’ve already died several times–the eight-year-old Nick ended and will never be again, so why should I worry if the 56-year-old Nick ends and will never be again; (2) I’m not trapped by past expectations of myself–I choose which part of my past selves I want to carry forward, just as I choose what parts of my parents beliefs and values I carry forward; (3) It helps my cope with the senselessness of people who “die young”–in my mind, their 2 years, or 8 years, or 25 years, on this planet are just as much a “full life” as my sequence of 20-year-lives.

Of course I think this applies to organizations as well. The IBM of 100 years ago is NOT the IBM of today, even though it is considered to be the same IBM through all those years. Organizations must celebrate their pasts without being trapped by them. I suppose EA can help organizations let go of the past while keeping the useful parts of it. This great quote comes to mind:

“[The dynamic forces of technology and the conservative forces of ceremony and ritual] oppose each other in dialectical fashion, and what is required for technological creativity is the right blend of accumulated knowledge of past generations and the ability to shed the stifling burden of past institutions.”

— The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress by Joel Mokyr, pg 190

@Nick: “To put it in stark terms, I act on the belief that for all intents and purposes, my 8 year old self is dead. I am his descendent, but I am not him.”

Yeah, a good way to put it.

My own experience is slightly different, though. I certainly wouldn’t say that my 3yr-old self is ‘dead’, because I experience it – or something very like it – when I see another kid jumping in puddles with rubber-boots. I feel that experience – it’s not a matter of abstract-thought, or memory, it’s much more direct and visceral than that.

Likewise when I reach out to sense how an organisation or some other context works as a whole, I do so with the same very ‘thin-skinned-ness’ as I had when I was a 20yr-old, a 25yr-old, where almost every interaction felt exactly like a huge risk of either being swamped, or flayed-alive, or both. (It’s why some types of EA work are utterly exhausting for me to do, now matter how important they may be.)

And, oddly, I’ve sometimes had kind of ‘reverse-time’ memories, things that I know that I sort-of experienced in previous times that only start to make sense now, or maybe a decade or so ago now but ‘old’ relative to when I first sensed them. Very difficult to describe, though – and of course impossible to ‘prove’ in any conventional sense.

But the point is that, for me, those ‘previous selves’ don’t quite ‘die’ in they way that you’ve described. It’s more like a rearranging of the threads of wyrd that appear and/or are directly-accessible at surface-level, whereas the overall clustering or set of threads that I experience or understand as ‘me’, at the deeper, less-time-specific level, seemingly remain much the same.

(Not disagreeing with you on any of what you said – and definitely not saying that your experience is ‘wrong’, because it isn’t. Just noting that the experience for me seems to be somewhat different, that’s all. Interesting, isn’t it? 🙂 )