Like magic…

What is magic? And how would it apply in enterprise-architecture?

Don’t worry – I haven’t gone crazy! (Well, not completely crazy, anyway…)

It’s just I’ve been doing a lot of pondering lately on that classic phrase by Arthur C Clarke, that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic“.

For example, consider its implied corollary, that “magic is indistinguishable from any sufficiently advanced technology”

In which case, what is ‘magic’? What makes something ‘magical’ – especially in a business-type context? Is it only the technology? If the magic fades – which it so often seems to do with any technology – how does it get lost? And what can we do to get it back?

First, though, what is that link between magic and technology?

For example, consider a small fragment of a scene in Pixar’s Brave, where the protagonist Merida first comes across the crazed crone who purports to be “only a woodcarver”. Over in a corner, there’s a broom, sweeping the floor on its own – which, to Merida, seemingly proves that the old woman must be a witch, a maker of magic. And yet, in the present day, we have semi-autonomous robots such as Roomba, that can likewise wander away on their own, sweeping floors – for as long as the battery lasts, anyway. Okay, they can’t quite manage stairs just yet, but hey, pretty magical, huh?

To give another example, I’m sitting in a cafe, chatting to a colleague in Australia, via Skype. His picture’s on the smartphone’s screen, gesticulating away: probably saying something, but no-one else can hear what it is, because I’m wearing headphones – and hence, in an almost literal sense, hearing his voice in my head. No wires anywhere: even the headphones are wireless. Barely any technology visible at all. And that’s pretty much an everyday scene nowadays, yes? Nothing magical at all. Not to us. Not now.

Yet talking with someone else – and seeing that someone else – on the other side of the world? In real-time? Even a couple of decades ago, that would have involved a lot of wire, and a lot of very visible technology, all at vast expense. A century ago, just about technically-feasible, but at truly fabulous expense – and voice-only at that, if we needed it to be in real-time. Go back a couple of centuries more, and people would explain such things more in terms of invisible angels; whereas these days – if we think of the technologies at all – we’d understand it more in terms of detail-level daemons. Times change, technologies change, perceptions change…

And yet, somehow, it’s still, well, magical, isn’t it?

It’s just that it’s so easy now to fail to see it as magical. That somehow the technology first almost blots out the magic – and then vanishes itself, seemingly leaving little but a blasé habit of everydayness behind it.

So what happened to the magic? Where did it go? Where did we forget the real magic that we once felt about such things?

Consider Steve Jobs’ product-launches, where he would often describe some new product, or features of a product, as ‘magical’: what was it that made such things ‘magical’? What was magical? How? And why?

And, equally important, why were and are some things not ‘magical’? Where and why did the magic fail to be ‘magical’? And if it once was, where did it go?

To me, the key seems to be this: magic is a feeling, technology is a thought. A technology always seems at its most magical when ‘it just works’ – it does what we’d hope it would do, and more, without any apparent assistance or effort on our part. Yet the magic vanishes whenever the technology becomes too visible – or, perversely, when we become so used to it that we barely even notice any more, because ‘it just works’.

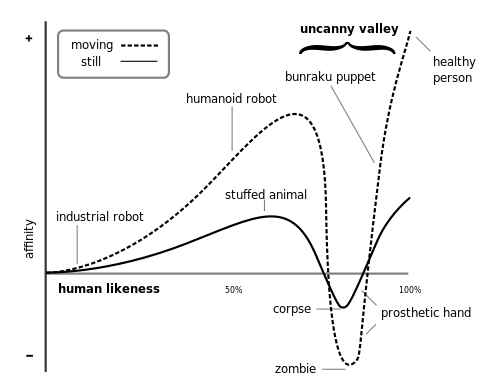

There’s a lot of layering in this, that in some ways reminds me of the robotics notion of the ‘uncanny valley‘. There, with increasing quality of the underlying technology, the personification becomes more and more magical, more and more human – and then, despite technically being better, kind of collapses into a weird creepiness. Only once the technology climbs towards an even higher level of perfection does that sense of creepiness fade:

Then there’s the technology-adoption lifecycle – ‘early adopters’ and all that:

And part of it, too, perhaps, is that when we focus on the technology, doing so in itself tends to destroy, or at least distract us from, that subtle magic. Mark Twain describes this transition well, in this quote from his 1883 book Life on the Mississippi:

Now when I had mastered the language of this water, and had come to know every trifling feature that bordered the great river as familiarly as I knew the letters of the alphabet, I had made a valuable acquisition. But I had lost something, too. I had lost something which could never be restored to me while I lived. All the grace, the beauty, the poetry, had gone out of the majestic river! … All the value any feature of it had for me now was the amount of usefulness it could furnish toward compassing the safe piloting of a steamboat. … Does [a doctor] ever see [a woman-patient’s] beauty at all, or doesn’t he simply view her professionally, and comment upon her unwholesome condition all to himself? And doesn’t he sometimes wonder whether he has gained most or lost most by learning his trade?

Linking those three themes together – this, the ‘uncanny valley’, and the technology-adoption lifecycle – there seems to be a kind of progression here:

— The first stage (Innovators and earlier) is about getting the whatever-it-is to work at all. That creates a lot of excitement – both for the onlookers (to whom it would seem ‘magical’ in the Arthur C Clarke sense above) and for the innovators (who are well aware of the difficulties of getting it to work, and hence that the fact that it does work at all will seem kinda magical!).

(During this first stage there is often no real distinction between technologist and artist, since the work seemingly requires an ability to work at the edges of both – or, in SCAN terms, way out on the far right edges of the frame. For me, for example, one of my formative influences – and perhaps a key reason why I ended up in art-college – was the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition at the ICA in London, which I would have seen in the summer of 1968, just before my last year at high-school. A quick search online turns up a BBC video on the exhibition, and another on one of the interactive sculptures, SAM, or Sound Activated Mobile. The exhibition and its associated catalogue [PDF] were hugely influential, both in general and me in person: for example, the artist and exhibitor Bruce Lacey was one of our visiting-lecturers a few years later when I studied at Hornsey College of Art. Perhaps most revealing for the present-day, though, is a comment by another of the exhibitors, cybernetician Gordon Pask, who “dismissed the digital computer as a kind of kinematic ‘magic lantern'”, and instead “saw mechanical models as the future for the concurrent kinetic computers required to describe natural processes”.)

— Next comes the initial stages of use as a working technology (Early Adopters). It still has a magical quality, not least because it’s useful as well – though the technology tends to be very ‘visible’, and by later standards will usually seem very clunky and awkward. In other words, the outcome has an air of the magical about it, even if the technology isn’t.

— The sense of magic still continues into the next stage (Early Majority), though more as what we might almost call a democratic form of magic – ‘magic for the people’ rather than ‘magic for the rich or eccentric’. (To give a personal example, I was absolutely fascinated by the early electronic-calculators – especially when the price suddenly came down to a level that even I could afford, as a struggling art-student in the early 1970s.)

— At the next stage (Late Majority) the technology has progressed to the point where the sense of ‘magical because it’s new’ has started to fade. Yet it’s at this point that the sophistication of the technology is also sufficiently developed that it starts to fall into the uncanny-valley; and the complexity has increased so much that Mark Twain’s ‘something was lost’ starts to hit hard amongst the technical community. On top of that, the Late Majority tend to engage because of fairly high expectations of ‘it just works’ – which the technology can’t yet guarantee to deliver, or even deliver at all. In other words, for almost everyone, it’s not so much ‘magical’ as almost its complete inverse – a near-rejection of the technology because it’s not yet “sufficiently advanced to be indistinguishable from magic”.

— The key to that final stage of the adoption-cycle (the so-called Laggards) is that they will only adopt a technology when its promises and expectations can be met in full. In other words, when it has developed far enough to climb back out of the uncanny-valley once more, and where ‘it just works’ really does mean ‘it just works’ – so much so that the occasional failures are acknowledged as rare exceptions, rather than fuel for yet further frustration with a ‘failed’ technology. That’s when it really is “indistinguishable from magic”, in that classic colloquial sense, where whatever-it-is runs by itself, doing whatever-it-is that we need it to do, in the background, and without much if any apparent need for our attention.

Implications for enterprise-architecture

This whole theme provides a kind of ‘double-whammy’ challenge for enterprise-architectures:

- the transition from novelty to first-use, and through the uncanny-valley to ‘it just works’, applies to adoption(s) for all technologies and processes in use in the enterprise – all interleaving with each at different stages in that sequence

- the same sequence applies to enterprise-architecture itself

To be blunt, the process and practice of enterprise-architecture is still barely at the Early Adopter stage. The obsession with IT-based technologies and Taylorist-style technology-centrism in general is very much holding it back, not least because the technology side – and its comcomitant Mark Twain ‘something is lost’ – still dominates the discussions so much that it all but drowns out the magic – the sense of wonder and possibility – that would help bring the much-needed Early Majority into the story.

To perhaps put it at its simplest, if the discipline of enterprise-architecture is to succeed in its aims, we need to find and reclaim the magic that’s inherent in every technology and in any enterprise-story, and hence in the story of enterprise-architecture itself.

Arthur C Clarke’s phrase that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” tells us quite a lot about how that magic is created; the story of the uncanny-valley, and Mark Twain’s warning, both tell us a lot about how that magic can be lost. Some very important lessons there, that we need to apply in and to our enterprise-architectures.

Yet there’s one further twist in this story. If, from all of the above, it’s true that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”, and likewise the technology-oriented corollary that “magic is indistinguishable from any sufficiently advanced technology”, then there’s also another implied inverse corollary, that “any sufficiently advanced magic is indistinguishable from technology“. Which takes us back into interestingly different realms… But I guess that’s something for another post – best leave it at that for now! 🙂

Over to you for comments and suggestions, anyway?

Interesting post Tom. I have 3 initial comments:

– Going back to your observation that magic is a feeling, technology a thought. What is that ‘feeling’ of magic really? I think a large part is the wonder of something behaving in a way not previous believed to be possible. In other words transgressing, in an inexplicable way, the boundaries of the known laws of reality. Naturally, once the initial wonder fades and we start to expect the magic to happen, we automatically adjust the boundaries of our known laws of reality so the ‘magic’ neatly falls within those boundaries. Since it falls within, there is no wonder left. It ‘just works’, as you rightly say, and there is no magic in something that ‘just’ works. After all, our body does many totally amazing things on a daily basis – and we barely understand how it works – but we don’t often think of our bodily functions as ‘magical’, because it does what we expect it to do. Only when someone, usually through long, dedicated training, does something exceptional do we get that feeling of magic again.

To summarise: we only feel the magic when something surprises us by seemingly transgressing what we think we know about reality. We then quickly adjust our expectations to include the magic in our new picture of reality, and the magic disappears into the realm of the ordinary. So I don’t think that the feeling of magic can ever be sustained beyond Early Majority, and maybe not even there.

– Another part of the feeling of magic seems to involve a sense of ‘mastery’. Something that behaves outside our know laws of reality but is not controlled by humans is more a ‘miracle’ than ‘magic’. Only when it is clearly subordinate to the human will would I call it magic in the truest sense. Maybe that is where the uncanny valley comes from: as long as we can see the human hand behind the magic we marvel at both its unexpected behaviour and the hand that made it happen. When the human hand disappears, however, but the behaviour is still somewhat unexpected or surprising, we get queazy and uncomfortable about it. We feel threatened by it because we cannot completely place it inside our known universe, and it is not controlled by someone like us. Then when the new behaviours become integrated into our known reality there is no feeling of magic left, and no need to see the human hand. It has now found its place, it is predictable again, and neither surprising nor threatening.

– To me to most promising area of magic still available to us is the magic of human collaboration. Think about it: people get together, do a lot of talking, doodling, shooting bits of text back and forth, and somehow, magically, something emerges that not only did not exist before, but was not even thought possible before, in fact, wasn’t thought of at all.

So I personally believe that the ‘technology’ Enterprise Architects should focus on most is the ‘magic’ of human collaboration and the complex adaptive systems that produces. Sure, there be dragons there, but many wondrous things beyond mortal comprehension as well.

Bard

P.S.

I wrote this in a bit of a hurry so I hope it is not too convoluted and confusing. I just felt that if I didn’t comment now I might never get to it at all.

Great comments, Bard! – really useful extensions to what I was somewhat fumbling with above. Many thanks indeed!