Bending reality

Do you believe in magic?

[Yep, this one is long – more than 7000 words, or long even by my somewhat-extreme standards for blogging. But there are good reasons why it needs to be this long, as you’ll discover later – and no, there ain’t no TL;DR here, for exactly those reasons. Anyway, back to the show…]

Do you believe in magic?

Nah – of course not – no way! That’s just silly stories for kids, right? I mean, we’re all adults here, all professionals, all serious scientific folk and all that?

Hmm…

Yet what about that old phrase from Arthur C Clarke, that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” – you’d be happy enough with believing in that kind of magic, wouldn’t you?

Well, yeah, no problem with that – of course that’s real – no question about that! That’s what we do every day with our technology, isn’t it? – we create magic!

So what about the logically-consistent inverse of that phrase, that “any sufficiently advanced magic is indistinguishable from technology”? – does that work too? And if not, why not?

Uh…

Hmm…

(scratches head, runs hand through thinning hair, puzzled expression on face…)

Uh… um…

Guess it kinda depends on what we mean by ‘magic’, doesn’t it?

And how we experience that magic, too.

Or, perhaps just as important, how well we can allow that magic to happen, so that we can experience it, so that others can experience it, through our work, so that…

Yeah. Kinda tricky, ain’t it?

The real catch is this: As enterprise-architects, strategists and suchlike, we’re in the business of bending other people’s realities. The whole point of what we do is that we’re bending reality-as-experienced into new forms – just like magic. So in a quite literal sense, we’re in the magic-business – the business of creating magic, of creating something new from, ultimately, nothing at all. (Nothing at all and a heck of a lot of hard work, that is – but that’s another part of the story!)

Yet there’s a fundamental trap, known as Gooch’s Paradox, that “things not only have to be seen to be believed, but also have to be believed to be seen“. Which kinda suggests that for any change to happen, anything new to be created, we first have to be able to believe in the existence of that ‘something’, that doesn’t yet exist.

In effect, we have to bend our own reality to include something that doesn’t exist, before there’s enough of a reality to give us the ‘evidence’ (literally, ‘that which is seen’) that would justify our belief in it enough to say that it can and does exist.

Kinda magic, right? – or something that’s a lot closer to magic than a lot of people might be comfortable to admit…

Professionally, though, we expect other people to do just that, with whatever it is that we’re telling them, for a new strategy or whatever.

Yet how well do we cope when it’s our reality, our supposed certainties, that are being bent out of shape? – because if we can’t do that, we’d be blocking our own access to that magic, which means in turn that we’d block other people’s access to that magic.

But no magic equals no change.

And no change equals no job for enterprise-architects and the like.

Oops: definitely tricky, that…

So, d’you reckon this is something that might be worth looking at?

[If you’re still reading at this point, I’ll presume that you think it is. Just a gentle warning, though, that we haven’t even got to the hard bit yet…]

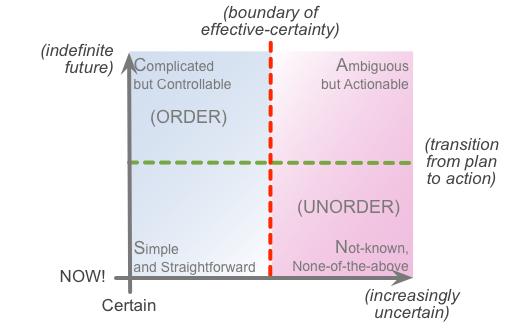

For the sake of familiarity and – I hope – clarity, I’ll drop in a SCAN diagram at this point:

Most of the time, most of us would want (and, probably, need) some form of certainty about whatever-it-is that we’re going to do. That’s how we get things done, that’s how we know that we’ve done what we intended to do, and all that stuff. In SCAN terms, that sits way over to the left of the frame, and, to get things done, we bounce back-and-forth across the ‘edge of action’, between theory and practice. Again in SCAN terms, we can move just about any distance toward and away from the ‘point of action’ – the baseline of the frame – but we stay well over to the left-hand side. As long as we stay to the left of that ‘boundary of effective-certainty’ – the red dotted-line – we might have some variation, but effectively we can be certain that the outcome should be what we expect.

The catch, of course, is that the real-world won’t always play by our choice of ‘the rules’ – sometimes it has its own very different ideas about what ‘the rules’ apply in any different context. Or, likewise, we might deliberately move over towards the right-hand side of the frame, because that’s where we get new ideas, new information, new anything. In fact it’s actually the only place where we can get new ideas, new information, new anything: and too much ‘need’ for certainty, for ‘control’, for assurance that we already have ‘the truth’ – actively blocks us from going there. As I described a couple of years ago in the ‘swamp metaphor‘ and ‘modes of sensemaking‘ posts, too much need for certainty about what is ‘true‘ and what is (supposedly) not, is what blocks us from reaching towards the often inherently-uncertain value that we need.

Value.

Otherwise known as ‘magic’.

In some senses, anyway.

The mapping between the SCAN and the swamp-metaphor isn’t exact – in fact arguably quite a long way from it – but it’s close enough to make it useful to show the swamp-metaphor modes in the same layout and colour-scheme as we’d use in SCAN:

So where the heck is all of this leading to, you’re probably asking by now? Well, this is where we hit up against a challenge, and a test.

The challenge to all of us is that the right-hand of the SCAN frame isn’t a simple linear scale: it goes all the way to infinity. Which means that every possibility will be there somewhere – including some things that you almost certainly won’t be willing to accept as ‘true’, and very probably a lot that you won’t be willing to accept even as having any possible value. And this especially applies when we’re working at or close to real-time, and we don’t have any chance to stop, think, assess, reflect. In SCAN I’ve made it slightly easier by labelling that space as a domain of the ‘Not-known’, but there’s a very good reason why the outerward edges are often described as ‘Chaos’: it is chaotic, and in many cases can be darn scary – at least until we develop our skills in ‘being comfortable with being uncomfortable’. Challenging indeed…

The main challenge comes from what I call a ‘mythquake‘ – something that shakes the foundations of our personal- and shared-myths, our assumptions and assertions about ‘how the world really works’. We go through many tiny mythquakes every day: for example, we expect something to happen, but it either doesn’t happen in the way we expect, or doesn’t happen at all. (And vice versa, of course: things that we didn’t expect that do happen.) Just as with earthquakes, though, there’s a whole scale of mythquakes – and every now and then we come across a real ‘biggie’ that’s very hard to cope with. But if we can practice on the smaller shakes, we’ll find it easier to cope with the bigger ones when they do come our way. And also help others to do the same – that’s important, especially in our kind of work.

In essence, a mythquake arises from a mismatch between belief and reality. Or, in SCAN terms, a clash between far top-left and (usually) far bottom-right of the frame – between expectations (certainties about the future) versus what’s really happening in ‘unexpected’ ways, right here, right now. Yet, courtesy of Gooch’s Paradox, the beliefs themselves make it difficult, or even impossible, to see or acknowledge any evidence that contradicts the belief – maybe preserving us from the immediate discomfort of the mythquake, but in reality making the disconnect from reality even worse. The danger is that the more tightly we hold on to those past certainties, the further we drift from reality – increasing the risk that the scale of subsequent mythquakes will ramp up more than we’d be able to cope with, because Reality Department won’t bother to wait for us to catch up.

If we think of mythquakes as a stressor for sensemaking and decision-making, then Nassim Taleb’s concept of ‘antifragility‘ applies:

“Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile. Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better”.

The challenge is a general one – it applies in every context, every part of life, for just about everyone. But we’ll perhaps see more than our fair share of it in enterprise-architectures and the like, because the whole point of what we do is that it’s about supporting and creating useful change – which, by definition, is going to create mythquakes of varying intensities, often for a lot of people. As a result, we’ll see that fear of mythquakes very often in others during our EA work, as they try to hold on to what they already know in contexts where it no longer works – and hence, if we’re to get anywhere in creating the changes we want and need, we also need to be able to help others get through their mythquakes.

Yet to do that, we’ll need a really good, practical, first-hand understanding of how those mythquakes work – and what we can do about them within ourselves. Which in turn means that we need to understand our own abilities and limitations in regard to Gooch’s Paradox – that things not only have to be seen to be believed, but also first have to be believed to be seen.

D’you reckon that’s something that might be worth putting to the test?

If so, here’s a fairly extreme test for you.

Perhaps as extreme a mythquake as it’s possible for most technical-oriented folk to face.

It’s called “Do you believe in magic?“…

Test structure

The test itself is in five parts:

- Introduction

- Examples (#1 and #2)

- Response

- Test

- Interpretation

A really important tip, though: keep going. Follow the process, right through to the end. In particular, don’t stop and give up in disgust as soon as you hit up against something you disagree with – because if you do that, you’ll miss the whole point of what I’m trying to show you. There’s a very, very important get-out clause to this whole thing, as you’ll see when we get to the actual test itself – but if you skip forward to that, you’ll again miss the point. It’s really important to sit with the discomfort, and not run away from it.

What I’m doing here is a bit unconventional – to say the least! – but it’s possibly the only way that’ll push your buttons hard enough to get the point across.

Introduction

(And yeah, this is where it gets real scary, for me, to talk about this, in public, in front of a ‘professional’-type audience, and probably Skeptical audience at that. But in the spirit of ‘Let It Go‘, here goes…)

I don’t believe in magic.

I also don’t believe that the sun will rise in the morning.

I don’t need to believe it, because I know it. That’s my experience.

And that experience in turn informs my beliefs. Which in turn inform what I can see as ‘real’, and what I don’t. Both for the rising of the sun, and for what many people would describe as ‘magic’.

In that sense – or, more precisely, in quite a variety of different senses – magic is part of my everyday reality.

For many if not most people, though, it isn’t. More precisely, it’s anything but part of their everyday reality. Even more precisely, they’re quite certain that it not only doesn’t exist, it can’t exist. At all.

Let’s assume that that latter assertion applies to you.

Let’s also assume that you’re capable of changing your mind about things, based on the evidence.

Yet straight away we run into Gooch’s Paradox: if you don’t believe it, how are you going to see any evidence that contradicts those existing beliefs?

What are the mechanisms via which you would reject any evidence that contradicts your existing beliefs, so as to protect those beliefs? For example, would you indulge in ‘shoot the messenger’ – even though all they’re doing is bringing evidence that you choose not to see?

And what would be the consequences if this information that contradicts your beliefs, and that you’ve therefore rejected, is something that you need to know – maybe even for your own survival?

Let’s put this to the test, with a couple of real-world examples. Watch how you respond – especially your emotional response – as you read these two descriptions.

Example #1

I’ll say straight off that this first example isn’t one that I witnessed first-hand, but it was told to me by someone who was there at the time, and whose opinions and competence as an observer I’d generally trust – a close friend named Richard. Here it is, as Richard wrote it down in what I believe is still an unpublished-manuscript, but which he allowed me to use in two books of mine. At the time – this would have been in the mid- to late-1970s – Richard was working as a professional recording-engineer:

It was quite late one night, and a couple of acquaintances in the music business and myself had returned from the pub to the recording studio complex not far from Ladbroke Grove. A member of our small party of travellers had left his bags in the studio reception area, and needed to pick them up before moving off homeward. Unfortunately, on arriving at the studio, we found the door locked. A heavy door, solid, about ten feet high by four feet wide I would guess, with a circular window in it. We peered through the window at the empty reception area where the security guard usually sat after hours, watching TV or listening to the radio. We rang the bell, and waited. Probably the guard was in one of the studio control rooms, chatting to tape ops as they cleared up after the last sessions of the night. Perhaps he was otherwise engaged. Whatever the reason, he did not answer the bell. We rang several times, but nothing happened.

Finally, one of our little group walked forward, inscribed some brief designs on the door [with his finger], and mumbled a few words under his breath. With a loud bang, the door swung almost wide open. The amount it opened was surprising in itself, as the door was on a very strong return spring. I reckon it would have taken the simultaneous impact of three people on the door to have the effect of opening it so far. In such a case, however, it would not have opened so rapidly as this one, which was just closed one moment and open the next. We went in before the door closed on its spring, and went over to the bags.

The door didn’t close completely, however: it couldn’t, as the tongue of the lock was still in the locked position. It could not pass the plate set in the door-frame, and hence could not close. Neither lock, door or frame were damaged, or marked in any way. It was as if the door had been unlocked, pushed open, and relocked in the open position. But this had not occurred … Neither had I been hypnotised, and so persuaded that the door had been opened by an invisible agency: that would not have got me past the door, and it would not have explained the bewilderment of the security guard when he finally arrived. What had occurred was a magical operation with an objective result.

Fiction, right?

Has to be, yes…? Couldn’t possibly be anything else, surely?

Well, maybe not… because a few years later, and entirely independently, I met up with one of the others who’d also been there. I’d written it up in a book, by that time, and he was almost aggressive about it – “How the heck did you know about that?” he’d said, halfway between a snarl and outright shock – and only quietened down I when explained the personal link with Richard. (He also added a couple of extra details, such as that the conversation in the pub had been mainly about practical experiments with Abramelin and suchlike; and that more than one of them had had a go at the ‘lock-picking’, but only one had had been able to make it work.) So yeah, this one could perhaps be considered confirmed, at the least in the sense of having been seen and experienced – whatever that might mean – by at least two independent first-hand witnesses.

Magic. For real. In the real, grubby, messy, awkward, everyday, how-do-I-get-this-darn-door-open world. Which can’t possibly happen. And just did. Hmm…

Example #2

This one’s a bit more personal, because it was a direct first-hand experience for me, some forty years back. I’d mentioned it, somewhat in passing, in the earlier post ‘Let it go‘, but let’s bring it front-and-forward here. (For reasons that would be obvious, I’ve changed the names of the other key players in this example, but other than that, this incident is pretty much exactly as I remember it.)

It was back at the time when I was still at Hornsey College of Art (now part of Middlesex University), nominally studying graphic-design. A few weeks earlier we’d been doing some studies with Keith Critchlow at the Architectural Association, and he’d introduced us to a couple of dowsers from Wales – both in late middle-age, one of them a country lawyer, the other a very experienced production-engineer – and they’d shown us how to get properly started on dowsing for ‘energies’ or whatever at stone-circles and the like.

Fascinating stuff – absolutely fascinating. But given my science background from school and suchlike, I was convinced that their approach to theory was rubbish: I was absolutely certain about that. Energies – what energies? Nothing in mainstream physics that would support any of what they’d said – though somewhat begrudgingly I acknowledged that their idea of ‘energies’ did sort-of work as live-metaphor. And they’d said that the pendulum moved on its own, whereas to me that couldn’t possibly be true: all of that part of the skill was straightforward anatomy, physiology and suchlike – the pendulum moved only because the hand moved it, the hand moved because a muscle twitched, the muscle twitched because of a nerve impulse, and so on. We could perhaps argue a bit about how the nerves were triggered in a reflex-type response, and the ways in which psychology can impact on those processes, but otherwise that was that. Definite. Certain. No other explanation.

So there I was, a couple of weeks later, sitting there on the steps in the old life-drawing room in the Crouch Hill building, during the long lunch-break between classes. It’s a big room, dating back to the later part of the 19th century, with high ceilings (for maximum light) and high-set windows (for privacy for the models); it was a cold winter day, and all of the windows were closed. I was expounding on my, uh, perhaps-too-certain theories about dowsing and the like to my friend Cassie, who this time had another student-friend with her whom I barely knew at the time, named Jen. I was showing them how to use the dowsing-pendulum, showing them how we can choose to use different movements and different directions to mean different things, and all those routine parts of dowsing-practice, as I’d later written-up in various books. But I then came to the bit where I said that the pendulum moved only because the hand moved. Never happens any other way, I said.

“Never?” said Jen. “Really?” She exchanged a glance with Cassie, kinda like she was getting confirmation that it was safe to go further. “That light there”, she said, pointing to one of the long light-fittings ten feet above our heads, hanging on their chains from the high ceiling. “That’s my pendulum, okay?” I nodded, not yet understanding what she meant. “Clockwise for yes, you said?” And that’s when I realised that the whole light-fitting was gently moving, swinging round, more and more, until, yes, definitely clockwise, as if seen from above. “And anticlockwise for No?” The light-fitting ponderously slowed to a halt, then slowly started moving the opposite way round. “See? Not always never”, she said, with a grin.

Yep: psychokinesis. Intentional psychokinesis. For real, first-hand, right here, right now, right in front of me. Ouch…

I took it quite well, I think. Even by then, I’d seen enough strangeness over the years to almost be able to take it in my stride. Almost. Probably what hurt most was having my cherished so-certain theories squashed flat in such an incontrovertible way… Oh well.

But what do you think about that?

If you think it didn’t happen, that I’m lying, that I’ve made it all up, that it’s all fiction – well, sorry, but it did, I’m not, I haven’t, and it isn’t. Jen is long since dead, sadly, but Cassie’s still around – in fact she lives not that far from here, now – and even corrected some of the details for me when we last met.

If you think I imagined the whole thing – well, possibly, but it would have taken at least two of us (myself and Cassie) to have had identical imaginations for that to happen. And even back then I’d been involved in that game long enough to have a pretty good idea of the complexities of the “Is it real or imaginary” question. Besides, we were all professional artists (or studying to be so, at least): we all had a fairly good understanding of what imagination looked like, and it wasn’t that.

If you think that, well, there must be some ordinary run-of-the-mill physical explanation, no can do – sorry. Windows and doors were all closed, so no big air-movements – and anyway, air-movement would have to have been more like a howling gale to move that light, because they were big and heavy. And just one light-fitting, but not the others? – tricky… Okay, what about ground-vibration of the building itself – traffic, or trains, for example? That one doesn’t work either: nearest underground-line is a couple of miles away at least – and that amount of movement for the light would have needed the equivalent of an earthquake almost strong enough to knock the whole building down. (I’ve been in major earthquakes, so do I know that one first-hand.) So, yeah, those usual physical explanations might be technically possible – just about – but if we apply Occam’s Razor to the context, they actually look less plausible than the not-so-usual ones. Sorry.

If you think that Jen faked the whole thing, like an illusionist would – strings and sealing-wax and all that fancy stuff – okay, yes, again, it’s just-about technically-possible, I suppose. But if we apply good old Occam’s Razor once more, it looks pretty unlikely. For a start, we didn’t know where we would meet up that day, we didn’t even know that we would all meet up on that day, and we certainly didn’t know beforehand which way the conversation would go.

So, just consider the possibility – the possibility – that it all happened just as I’ve described it. What would that do to your sense and certainty about what is possible and what is not?

Response

What’s your response to those two examples above? (I could have given you quite a few more examples from my own experiences, but those two will suffice for this.)

For example, you might start with this:

- Absolutely impossible!

- Can’t possibly happen!

- Obviously faked!

- Utter load of [excrement of male bovine quadruped]!

A lot of people would go on to make this a good deal more personal:

- Tom’s really flipped his lid this time – he’s gone completely crazy!

- I knew that guy [me] couldn’t be trusted…!

And a fair number of people would derive other assumptions:

- Obviously incompetent at any kind of science or technology!

- If that’s what he thinks, then his work on enterprise-architecture must be utter garbage too…!

A few folks – particularly those who know me in person – might also, or instead, throw in some responses that are rather more quizzical than disparaging:

- What’s he up to this time?

- I know he’s a bit weird, but…?

- Watch out – another Tom-style monkey-wrench coming up?

Whichever way you’d look at it, and me, note down your response. And note especially the emotion that goes with that response: disparagement, disgust, derision, doubt, or whatever.

Don’t worry, you don’t need to be ‘nice’: be as rude as you like. If you think I’m an utter nutcase for talking about those kinds of experiences above, that’s absolutely fine. Just take care to note the emotion that goes with it, that’s all.

Because, yeah, this is where we really meet up with the sting in the tail…

Test

Your response represents a decision that you’ve made, based on the nominal information that I gave above.

There’s likely to have been a fair amount of emotion attached to that decision.

There are quite likely to be some associated decisions about the competence or otherwise of the messenger for that message – in other words, me.

All of which response you’re likely to describe as ‘rational’ – maybe even as ‘the only rational response’.

Just about all of us, I’d imagine, would expect rational decisions should be made on the basis of facts.

Yet what exactly are the facts in this context?

So here are the actual facts:

- I wrote what purports to be an as-close-to-factual-as-possible description of two purported events.

- You have no actual means of verification or rejection for any of the purported detail provided about those events.

- You have no actual verification as to whether either of those events actually took place – all you have is the description itself.

- You have no direct access to further information on those purported events.

- In particular, you were not personally present at either of those purported events, and therefore not competent to give any judgement about those events, based upon your own experience of those events.

- Ultimately, the text itself is the only accessible fact, not the purported events – the text that you’re reading, not the content of the text.

- The one thing that science tells us for certain is that we still do not know everything – especially about seemingly ‘one-off’ events.

All of which tells us that any certainty-based response that you may have had to those descriptions would’ve had to have been based on the following:

- Arbitrary assumptions, based on presuppositions about valid versus non-valid theory – in a context for which you do not actually have any concrete evidence at all.

- Emotional defence of supposed ‘certainties’ – for which you have neither evidence nor proof, for that specific context.

That’s it: no other possibilities.

So, given all of that, here’s the test:

- Just how disparaging, dismissive, derisory or doubting were you? – of the description, the context, and/or me?

- Given that you had no actual evidence for any of those assertions in your response, what does that tell you about the quality of your own decision-making in the face of the ‘Not-known’?

- Given the probable extent of emotion used to underpin that decision-making, what does that tell you about the extent to which your nominally-‘rational’ decision-making is not actually rational at all? – especially where it faces the ‘Not-known’?

Or, in short, the extent to which you were derisory, dismissive and rude in your responses above is an indicator of the extent to which you actively prevent yourself from seeing just how non-rational your supposedly-‘rational’ sensemaking and decision-making processes really are, in the face of the ‘Not-known’ – and also the extent to which you fail to resolve Gooch’s Paradox in real-world practice.

Not clear yet?

Let’s go over it one more time:

- The only facts above were that you had a bunch of second-hand information, without any first-hand in-person context of your own.

- You are likely to have made what you would consider to be a ‘rational’ response to that information – including a probable ‘shoot the messenger’ component of that response.

- Yet any decisions and interpretations that you made about the content of the information itself were not and could not be based on fact, because you had no access to concrete fact about it.

- Hence your response to that information was likely not based on facts, but emotional defence of arbitrary beliefs and presuppositions – the exact inverse of ‘rationality’.

In that sense, the extent of rudeness and suchlike in your response above is a direct metric of how much you fail to manage Gooch’s Paradox and, probably, fail to cope with real-world mythquakes. And actively prevent others from coping with them, too.

Ouch…?

Ouch…

Interpretation

Don’t worry: everyone fails this, to varying extents. (I certainly fall into it from time to time, anyway, and I don’t know anyone, or of anyone, who doesn’t.) Yet kinda scary, huh?

But if I’ve done my job properly here, that test just above should have given you quite a nasty shock – a nasty wake-up call. And also a first-hand experience of a mythquake about the real nature of mythquakes.

Note too that, for my test-case for this little experiment, I only chose “Do you believe in magic?” because I know that most people don’t. 🙂 It doesn’t matter whether or not I believe that magic exists: what matters is how you shut out the possibility that it might – and how your decisions about that, that claim to be ‘rational’, are probably not rational at all. That’s what I’m hoping to show you here.

And anyway, it’s not about ‘magic’, or anything like that at all. In practice, I could have used almost anything for this, and, as long as the purported ‘facts’ were different from your beliefs, the effective result – the response – would have been almost exactly the same. Anything: including your everyday beliefs about everyday enterprise-architecture and the like.

Ouch…?

Yeah – that’s where the real ‘ouch’ lies…

To use SCAN terminology, in essence what’s happening is that you’re faced with something way out on the lower-right of the frame – real-world, real-time incident, unusual to the extent of perhaps being entirely unique, inherently unknown and probably unknowable – but you’re trying to tackle it via ‘Complicated’-domain techniques that are valid only for the upper-left of the frame – the certainty of ‘proven’ theory.

In other words, diametrically opposite to what we’d actually need to use for that type of ‘Not-known’ context:

That’s almost the definition of the cause of a mythquake: a misplaced assumption of certainty about something that’s inherently uncertain.

In a bit more detail, though. What’s going on is that, for most of the time, we rely on our real-world responding well to ‘Simple’-type rules, regulations, work-instructions, that sort of thing. But when something happens in real-time that doesn’t fit those expectations, what that should normally do is throw us briefly over the ‘edge of panic’ into the ‘Not-known’ domain, where we can work on it with the techniques appropriate to that domain (emergency-checklists, for example, and guiding-principles). In SCAN terms, all of this happens in the ‘horizontal’ dimension, at or close to the real-time baseline of ‘NOW!’.

The catch is that – to put it into its simplest terms – going over the ‘edge of panic’ is, by definition, scary, or worse. Hence there’s a ‘natural’ tendency to try to hold on to what seeming-certainties we have, and run away in the only other direction that’s available to us, the ‘vertical’ dimension in SCAN, away from real-time, back over to the theory-oriented side of the ‘edge of action’ – the domain of the ‘Complicated but still seemingly controllable’:

Which looks like it works; which often feels like it’s worked; but the giveaway clue that something’s not right is the unresolved emotion. By running away into theory, we’re pretending to have crossed over the ‘edge of panic’ and back again – but we haven’t actually done so. And in order to conceal the fact that we haven’t actually resolved anything at all, we collapse Gooch’s Paradox: we ‘resolve’ the paradox by insisting that “things have to be seen to believed” in terms of whatever theory that we’ve chosen, so that we can exclude anything that doesn’t fit, and thence ‘justify’ not actually dealing with the real messiness of the real-world at all.

In short, wherever this happens:

- theory takes precedence over practice

- opinions are confused with facts, or used as substitute ‘facts’

- actual facts are ignored or edited so as to fit in with the expectations of theory and opinion

Overall, not a good idea…

The crucial clue is the level of emotion. An alternate term for ‘belief’ in this context is ‘religion’: belief as in a creed or credo – literally, ‘I believe’. Hence whenever a significant level of emotion is involved in any discussion about supposed ‘facts’, we’re probably in the realm of religion, not ‘science’.

And if we’re in the realm of religion, it’s probable that no amount of factual evidence is going to change the belief. Gooch’s Paradox fails, because whatever-it-is is not believed, therefore cannot be seen.

Changing belief is not a ‘rational’ matter: it’s (much!) more an emotional one. But without changing beliefs, we can’t see anything different, anything new. So to create any kind of useful change, we somehow we have to be able to get people (including ourselves) over that barrier of ‘the edge of panic’, and properly face the ‘Not-known’ – rather than running away from the ‘NOW!’ and hiding in the safety-blanket of our supposedly-‘rational’ existing beliefs. And that’s not easy for anyone.

What Gooch’s Paradox really shows us is that a belief is a self-contained structure, continually self-confirmed and reaffirmed via circular-reasoning based a (usually) self-consistent logic: “things not only have to be seen to be believed, but also have to be believed to be seen”. And most of what we do in real-time is driven by such self-confirming, self-circular beliefs, if only because there’s no time available for anything else: doubt is often a luxury we can’t afford when we’re working right at the edge of right-here-right-now.

Yet by definition, we can’t change a logic via the same logic itself: it just doesn’t work that way. We have do it kinda sideways, kinda sleight-of-hand – like magic, you might say. But the only way that that’s gonna work is if we’re fully aware of the ways that emotion comes into play in this kind of context – and learn how to work with it, rather than pretending that it doesn’t exist.

[By this point I’d hope you’ll now see that this post – especially this ‘challenge-and-test’ section – really did need to be this long, for you to be able to see what’s actually happening in this type of context. If I’d simply asked ‘Do you believe in magic?’, your answer would probably have been ‘No’ – yet you also probably wouldn’t have been able to see the emotion that actually underpins that decision. It’s the emotion behind the so-called ‘rationality’ that’s the crucial concern here.]

The key point, though, is now that you know that it happens – and, even more to the point, that it happens in you – what are you going to do about it?

Kinda tricky, yes…?

Implications for enterprise-architecture

Gooch’s Paradox is hugely important in enterprise-architecture, both in our everyday work with clients and stakeholders, and for the discipline of enterprise-architecture itself.

One of the reasons why it’s so important is that, in real-world practice, enterprise-architecture is more akin to alchemy than applied-science. There’s so much inherent-uncertainty and uniqueness around what we do – much of it of necessity, and/or by intent – that often we simply don’t have the option of using the nice safe certainties of a supposed applied-science. Which leaves us, in practice, very much in the realm of opinion and belief.

(And experience, too: experience really matters here – often much more than so-called ‘science’. And yet we also have to be able to transcend that experience, in order to learn new experience, allow new experiences in. Kinda tricky: Gooch’s Paradox again…)

It matters in our everyday work because we deal with many, many different stakeholders and stakeholder-groups – and every one of them will have their own specific and literally peculiar beliefs. Somehow we have to bridge across all of them, accepting that each and every one of them is ‘right’ from their own perspective, and that each one of them is also likely to hold a key part of the puzzle that we have to solve and/or ‘re-solve‘. (One of de Bono‘s ‘laws of thinking’ also comes to mind here: “Every is always right, and no-one is ever right” – everyone is correct from their own perspective, but no-one holds the whole picture.) The catch, of course, is that almost every one of those people will hold that same emotion-based certainty that we saw in the ‘challenge-and-test’ above, that they alone are right, and that therefore, by definition, everyone else is ‘wrong’: hence lots of, uh, fun – such as in the infamous chasms of misunderstanding that drive ‘IT/business divide’…

And it matters to the discipline of enterprise-architecture itself, in essence for exactly the same reasons. Although there are some few elements that we might perhaps describe in some few places as a sort-of-science, the reality is that, by its very nature, enterprise-architecture is not a science, and never will be – at least, not in the sense that most would currently think of as ‘science’. Yet when people think it is science – or that their version of it is ‘science’, anyway – that’s when we get all of those, uh, joyous fights and feuds about EA, on LinkedIn and the like. Once we realise that, given that clue about oddly-misplaced emotion as a sign that Gooch’s Paradox has failed, what we’re dealing with there is closer to religion than it is to science, it becomes somewhat easier to manage – or, often, more usefully, just avoid…

Yet somehow, of course, we do have to make it work: we do have to bridge across all of those different ‘truths’. The way out, it seems – or that’s my experience, anyway! 🙂 – is to learn how to use beliefs as tools, not ‘truths’. Stan Gooch summarised this well in a comment about research on parapsychology, which I’ll paraphrase somewhat here:

Whilst undertaking any enquiry, accept every statement at face-value, exactly as if true – whilst keeping one small corner of your mind aware that it isn’t.

Note that point about ‘as if‘ true, not ‘is‘ true – that distinction would often seem subtle, yet is absolutely crucial here.

In SCAN terms, it’s about working with the full knowledge and acceptance that, by definition, we’re exploring in context-spaces that are often far over to the right-hand side of the ‘boundary of effective certainty’, dealing with the inherent unorder of the Ambiguous and the Not-known’:

In the sciences, it’s about how we work with ideas, experiments, hypotheses – where the whole point is that we don’t yet know what ‘the answer’ might be. Two science classics that I often refer to for guidance on this are Paul Feyerabend, Against Method, and WIB Beveridge, The Art of Scientific Investigation – both books strongly recommended for enterprise-architects and the like.

For the, uh, more adventurous, there’s a whole domain or discipline that explicitly works on and with this manipulation of belief, known as Chaos Magic. A lot of it, I’ll happily admit, is way outside of my own experience and taste, but there actually is a lot of value to be found there. One of the more accessible – and certainly eye-opening, if in a carefully metaphoric sense – of the Chaos Magic texts is ‘Ramsey Dukes’, SSOTBME: again, recommended, though perhaps only if you’re willing to accept the ‘occasional forays into the overly implausible’ (as was once said about one of my own books!). Although he now lives in another country, I used to know the author quite well: he once said to me that his greatest challenge, as a professional mathematician working in aircraft design, was to make his mathematics sufficiently imprecise to be useful – and he really does know his stuff.

A context in which both science and magic necessarily co-exist? – yeah, it can be a weird world we’re working in, all right… 🙂

Yet to come back to the key points here:

- as enterprise-architects, our work is all about creating change

- creating change necessarily requires changing people’s people’s minds, changing their beliefs – including our own

- within this work, one of our key stumbling-blocks is Gooch’s Paradox – that “things not only have to be seen to be believed, but also have to be believed to be seen”

- an often-subtle yet oddly misplaced emotive-response is a key clue of failure to resolve Gooch’s Paradox – a misplaced attempt to hold on to inappropriate ‘certainties’

- to get past the fears around Gooch’s Paradox, we need to acknowledge the emotion, and accept every assertion as if true – which is not the same as accepting that it is ‘true’

- tools, techniques, practices and disciplines to work with these concerns already exist in a variety of domains – from science to magic, and more – and as enterprise-architects, we would be well advised to learn them, and apply them in our work

We might call ourselves ‘enterprise-architects’, but in reality we’re magicians: we’re in the business of bending reality – like magic. (Okay, it’s probably more a commercial- or business-oriented form of magic, it’s true, but still a kind of magic nonetheless.)

And Reality Department, too, has an, uh, interesting habit of bending our reality for all of us, anyway, whether we like it or not. (In business and technology, we might call it ‘disruption’ – which, however, often feels a lot less than fun if it’s our world that’s being ‘disrupted’…)

So perhaps the real warning here is this:

If we can’t allow our reality to bend, it’s likely to get broken for us.

If we allow our clients and stakeholders to refuse to permit their reality to bend, it’s likely to get broken for them.

In a context that’s undergoing rapid, accelerating change, if we ever allow our predefined ‘explanations’ to take precedence over experience, we’re in deep trouble – because that’s when we lose the magic, and worse.

Something to consider carefully, perhaps?

Tom:

Awesome article! I have long thought that you couldn’t sell EA to people who require a measurable cost/benefit ratio to be proven to them before they will consider it. It seems only to be adopted by those that intuitively believe that their enterprise will work better if they take an EA approach to its design.

Gooch’s paradox and the content in this post go a long way to explaining why.

Thanks

Many thanks indeed, Howard – it really does help me a lot to know that at least one person has truly understood what I’d tried to explain here! 🙂 (It’s been a very, very hard road… 😐 )

Hey, Tom — Thanks for this posting, which fits nicely into the context I have given our one in-person meet-up at my Alma Mater. The whole subject of belief as something accepted to the point of being unbudgingly unchangeable is the root of most human woes, especially when it leads to classification of fellow humans into ‘us’ and ‘them’.

The way this manifests for me in the EA realm is the position I’ve held for decades that human collectives (as well as collectives in other species) constitute a form of life beyond the biological. Systems that have emergent properties that can’t be reduced to the properties of the individual participants. I explored that idea in a LinkedIn group for awhile (Living Enterprise). I’ve let that group go dormant, partly as an experiment in how these things work, but there’s some good stuff captured there. My mantra at the time was “It’s not a metaphor!” and the exploration of that phenomenon so far seems to me to be on a fairly primitive level. What excites me these days is to entertain concepts such as the VSM homeostat, the Geek Heresy amplifier, the moral hazard, the opinion echo chamber, the effort rheostat, and others in terms of their explanatory and predictive power.

By the way, I can’t personally make chandeliers move from afar, and I’m not sure I aspire to that power. I have an intuition that the “possession goes both ways” principle might apply, so I’m happy to live among the gifts that seem to work for me. Keepin’ an open mind though, dontcha know?

@Doug: “The whole subject of belief as something accepted to the point of being unbudgingly unchangeable is the root of most human woes, especially when it leads to classification of fellow humans into ‘us’ and ‘them’”

Sadly true… 🙁

@Doug: “By the way, I can’t personally make chandeliers move from afar, and I’m not sure I aspire to that power.”

I can’t and don’t, either, not least because I was told by ‘Cassie’ a few years back that ‘Jen’ herself had died in a psych-ward not too many years after that incident… – bending reality that far kinda puts too much strain on the system, especially when other more-easily-frightened-but-unbudgingly-unchangeable people are around… 😐

(I few decades back used to teach dowsing [US: ‘water-witching’], which is often mislabelled as ‘paranormal-therefore-impossible’, but in practice is just a perfectly-straightforward sensemaking-decisionmaking-action loop with a few odd twists here and there. Yeah, it can sometimes sorta bend people’s reality a bit, but nothing on the league of either of those two incidents above! But then these days I mostly do enterprise-architecture and business-change and thinking-about-thinking and the like, which for most folks seems a lot scarier than mere water-witching! 🙂 )

Hi Tom,

I’d had like to react to this awful post. But, my comment (Uhh, became to lengthy as above your Yep 🙂

So, I’d dropped yesterday a longer personal email to your email address got from your LinkedIn contact info.

Nothing expected to reply, only if you feel that worth, (although I’d receive that gladly :), I only ask you to send back me the return receipt whether you received that mail or not. Much tanks,

Remaining with high admiration,

Valeria

Hi Tom,

I’ve just got our mail reply to this comment. Much thanks for it.

I answered that mail and attached to it my previous mail.

Why you did not get it at first, I might only guess.

(I sent it to your proper mail address.)

So to check sooner, if it can happen again, I ask you to send me back the return receipt of my answer mail to which that previous mail had been attached, before your reply.

Much thanks.

Sincerely

Valeria