Beware of ‘policy-based evidence’

The other day I spotted an interesting article (cite: BMJ 2014,349;g5538) in the print-edition of the British Medical Journal, about the dangers of premature decision-making based on what they described as ‘policy-based evidence’.

The article’s examples were in healthcare, of course, in particular about politicians declaring ‘success’ over some pet project, on the basis of noticeably-selective short-term ‘evidence’ – ‘success’ that in the longer term, when faced with more rigorous assessment, turned out to be of limited value at best, or, too many cases, expensively worse-than-useless.

Part of this is an inverse corollary of Gooch’s Paradox, that ‘things not only have to be seen to be believed, but also have to be believed to be seen’. In this case, only that which is believed becomes that which is seen – ‘evidence’, in its most literal sense of the term – with all counter-evidence ignored or dismissed from view precisely because the possibility of its existence is not believed.

It arises from any of a whole suite of cognitive-errors, ranging from excessive-zeal to groupthink to scientific-incompetence, and onward all the way to outright fraud. We need to be aware to expect it wherever there is some form of vested-interest, whether personal, social, commercial or whatever: hence, for example, the all-too-common dangers implied in the old warning of “never expect some to ‘get it’ if their income, job or status depends on not getting it”.

The real danger is that ‘policy-based evidence’ is frequently used to support policies based on circular-reasoning. In business, the more obvious examples include IT-centrism and managerialism – respectively, that ‘the answer’ to any business problem is more IT, or more managers and more managerial ‘control’. (The two are often blended together, of course, with IT providing the supposed means for ‘control’.) It also happens very often in social contexts, leading to racism, sexism, iniquitous ‘economics’ and more – though I’d perhaps best write a separate blog-post about that.

(Perhaps the most extreme and egregious example of ‘policy-based evidence’ that I’ve come across over the years was the now-infamous national ‘Women’s Safety Survey’ commissioned by the Australian government’s Cabinet-level Office for the Status of Women (back in the late 1990s, as I remember?): they published the ‘official results’ of the survey, and set out all of the resultant ‘evidence-based’ policies, before Statistics Australia had had any chance even to start on designing the survey!)

The blunt reality is that, for viable policy and system-design, it’s essential to think in terms of whole systems, not arbitrarily-isolated linear-causalities – otherwise we will inherently exacerbate or even create ‘wicked-problems‘. Instead, in circular-policy – policy based on circular-reasoning and ‘policy-based evidence’ – an arbitrary subset of a whole system is selected as ‘the problem’, and, very often, a single element interacting with or within that subset is arbitrarily selected as ‘the cause’. Attention is paid only to the impact of that ‘the cause’ on that ‘the problem’: this may be either positive (‘the cause is the only answer to the problem’) or negative (‘the cause is exclusively to blame for the problem’). From the outside, and from this specific perspective, it all seems to ‘make sense’, and fits well with the kind of linear, non-ambiguous, non-systemic models of causality that so many people still seem to prefer – whether or not they can actually be relied upon in any real-world context. Yet because attention is paid only to that one purported ‘the cause’, what we get from it is ‘policy-based evidence’ – that self-selected subset of the whole. And since the ‘evidence’ supports the assumptions of the policy – because it is selected to fit the assumptions of the policy – this is then taken as justification and ‘proof’ that the policy itself is correct. In other words, a perfect self-confirming circularity – explicitly excluding any means to test against a broader reality.

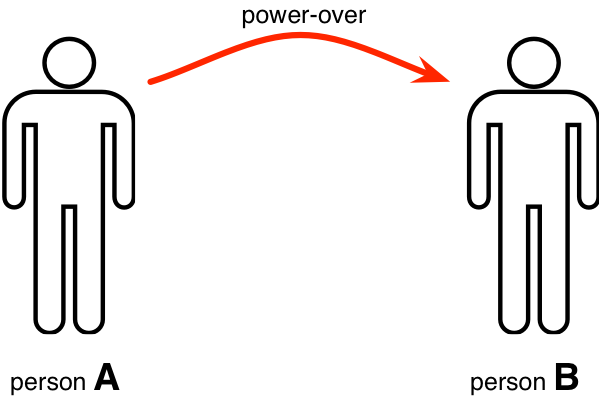

Let’s take a classic example: bullying at work. The common notion is that there is a simple linear causality: hence, there’s a perpetrator of the bullying (person-A in the diagram below), and a victim (person-B). The bullying is assumed to be only one-way, from perpetrator to victim: to use a term first proposed by feminist theorist Starhawk (in either Dreaming the Dark, or Truth or Dare, as I remember?), the perpetrator applies ‘power-over‘ to the victim, with person-A ‘propping self up by putting down the Other [person-B]’:

If we take that view, then we’d likely look for evidence that fits that model of bullying – in other words, ‘policy-based evidence’. On the basis of that, we’d seek, for example, to punish the person-A, as the ‘sole-perpetrator’, and provide succour and support for the person-B as the ‘the sole victim’. All of that ‘makes sense’ within the terms of that kind of model, and is a typical basis for many organisations’ policies on workplace-bullying.

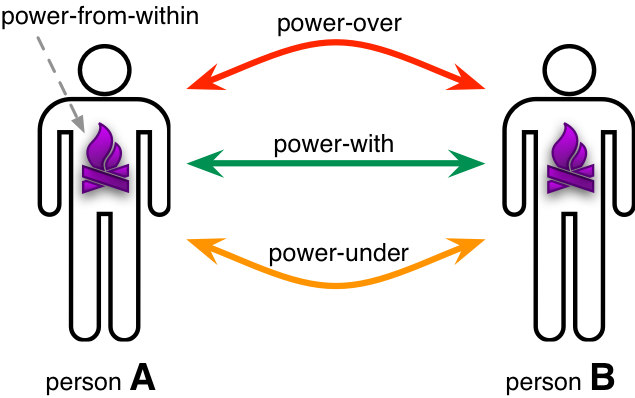

Unfortunately, it happens to be based entirely on circular-reasoning. If we use instead the overall power-model that Starhawk proposed (or, strictly speaking, a somewhat extended version of that power-model*), it’s systemic, not linear – that supposed one-way ‘power-over’ is merely one arbitrary-selected snapshot within a much more complex interweaving of several distinct forms or threads of power:

(*Note: ‘power-under’ – ‘offloading responsibility onto the Other without their engagement and consent’ – is not described in Starhawk’s original power-model, but is a necessary corollary to the nature of ‘power-over’, and also as implied in real-world observation of dysfunctional power-relations. The closest colloquial terms for power-over and power-under are ‘violence’ and ‘abuse’ respectively.)

Starhawk argues (and I’d agree with her on this) that in any human context, the only real source of power is from within the self – what she terms ‘power-from-within’. She also suggests that a core role of interactions between people is to assist each other in finding that ‘power-from-within’ – an interaction and relationship that she describes as ‘power-with’. In contrast, both power-over and power-under seek to suppress and/or co-opt the other’s power-from-within, following the common delusion that power can be ‘taken’ from others.

That power-model warns us that these power-interactions and power-dysfunctions are much more complex than a simple linear ‘A bullies B’: there can some very tangled twists, such that, in reality, person-A – the supposed ‘perpetrator’ – may actually be much more the victim of person-B, who is using power-under to ‘play victim’ in order to get others to bully person-A on their own behalf. If all we have is policy-based evidence, then that ‘evidence’ itself becomes a means of abuse of person-A – which would succeed only making things worse. But since the policy itself is circular, making things worse would be taken as ‘proof’ both that the policy itself is ‘correct’, and that more and more abuse should be piled upon person-A, ‘the perpetrator’ – eventually driving the whole mess into a non-recoverable death-spiral. Not wise at all – but depressingly common…

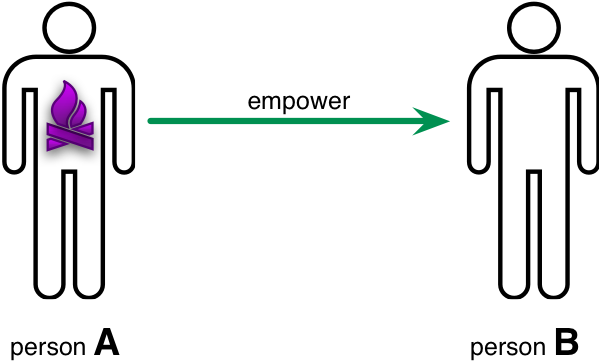

Okay, some people might object to that example, so let’s move to a somewhat less controversial one: the usual notions of ‘empowerment‘, in the business-context and elsewhere. In those usual notions, person-A – the boss, for example – ’empowers’ person-B to do something. Or, in short, person-A supposedly gifts person-B some of their power:

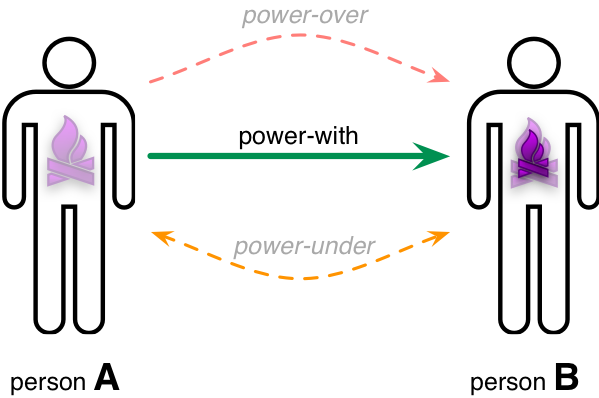

Again, we’ll often see ‘policy-based evidence’ at work here, ‘proving’ that person-A ‘gave’ person-B some of their power, and that person-B should therefore be grateful to person-A for their great gift, or some other such guffleblub. But in reality it’s just another example of self-congratulatory circular-reasoning – because if we reframe that context in terms of the power-model above, a very different picture emerges. As Starhawk says, the only source of power is from within the self: so if person B needs to find the power to do some task – following a physics-style notion that ‘power is the ability to do work’, though with ‘work’ being in the broadest possible sense – then the only source of the power to do that work is from within person-B. At most, all that person-A can do is apply power-with, to help person-B find their own power-from-within. What person-A provides as power-with to person-B is, arguably, indeed a gift, but it’s not power itself, power-from-within – a subtle yet often utterly crucial distinction:

We might note, though, that whilst ’empowerment’ is largely a fiction, disempowerment is all too real – either actively suppressing the Other’s power through power-over, or, in the reverse direction, attempting to co-opt the Other’s power through power-under. In practice, ’empowerment’ is often little more than a misleading code-word for person-A cutting back somewhat on their habitual power-over towards person-B, or person-B cutting back on their habitual dumping of responsibility onto person-A via power-under – both dysfunctions being extremely common in hierarchy-based ‘boss/worker’ or ‘superior/subordinate’ relationships.

In both of these examples – bullying, and ’empowerment’ – any form of ‘policy-based evidence’ will invariably lead to and underpin policy-driven circular-reasoning, itself based on a linked chain of arbitrary and unexamined linear-assumptions in what is actually a non-linear systemic context. So watch for, and beware of, ‘policy-based evidence’: it’s sometimes hard to spot, often politically-problematic to critique, but if unchecked and unchallenged it will always make things worse. Yet another You Have Been Warned item for enterprise-architects, perhaps?

Implications for enterprise-architecture

Enterprises and organisations of all kinds are riddled, flooded, with ‘policy-based evidence’ – so much so that it’s almost a sewer of misinformation in which we’re all forced to swim. The problem – particularly for enterprise-architects – is that, especially if left unchecked, every instance of ‘policy-based evidence’ has potential to cause serious damage to the overall enterprise. It is not something that we can safely ignore.

First, we need to be able to identify ‘policy-based evidence’. What makes this hard, and potentially problematic in a business-politics sense, is that ‘policy-based evidence’ is so much ‘the sewer in which we swim’ that it can seem ‘normal’, and/or that highlighting any example at all from that flood of effluent may itself be misinterpreted as some form of bias or prejudice on our part. (That latter point is a real concern, of course, and we’ll come back to it in a moment.) To make a start, though, look for some of the more blatant clues, where:

- attention is continually dragged back to a single ‘the cause’ or ‘the solution’ – IT-centrism is a classic example of the latter

- there is explicit rejection (or even active silencing) of counter-evidence or counter-examples – “that’s only a special-case, it never happens”, “the exception proves the rule”, etc

- there are hints and more of ‘follow the money’ – the interests of a self-selected individual or sub-group have been arbitrarily prioritised over the aims and balances of the enterprise as a whole

Having identified a potential example of ‘policy-based evidence’, model the respective context as a mutually-interactive, mutually-interdependent system, so as to highlight hidden assumptions that underpin the purported ‘evidence’. However, it’s crucially important to:

- model the system in an open and transparent manner, highlighting all assumptions made in the modelling process – to counter any accusation of bias or prejudice on our own part

- counter and resist all attempts to force the modelling back into a subset linear-causality frame – in some cases the pressures to give in on this point may be very large indeed, but surrendering to a linear-causality-only view of a systemic context will allow the hidden assumptions behind the ‘policy-based evidence’ to be re-concealed, and will defeat the entire object of the modelling exercise

For the modelling process itself, three frameworks I’d often suggest are Nigel Green and Carl Bate’s VPEC-T, Sohail Inayatullah’s Causal Layered Analysis, and one of the crossmaps for my SCAN framework.

In VPEC-T, we explore the context in terms of five dimensions:

- values – “Identifies the important principles and goals in play, allowing conflicts that may cause confusion to be identified and resolved.”

- policies – “Identifies specific practices and guidelines that the system must adhere, allowing conflicts to be identified and resolved.”

- events – “Identifies the trigger points that indicate the change in state of processes or otherwise important milestones.”

- content – “The core content of the information-system [more generally, the system as a whole, including all its content-dimensions] is clearly identified and put into context of the desired outcome.”

- trust – “Trust relationships are identified. Existing areas of mistrust are identified and addressed. Opportunities to build trust are searched for.”

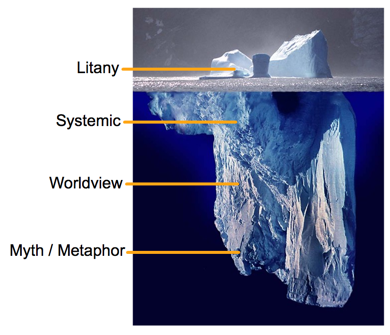

In Causal Layered Analysis, we move up and down a ‘stack’ of layers of perspectives, worldviews and deep-story:

- litany – the ‘surface’ layer of everyday-complaints, often laden with blame and counter-blame

- systemic – in practice, more like a meshwork of rarely-examined assumptions about linear-causality

- worldview – probably the core source of filters and assumptions about ‘how the world really works’, and hence what would be included in and excluded from a linear-causal ‘systemic’ model

- deep-myth – existential metaphors (e.g. ‘life is unfair’ etc) and deep-stories – often the only place where deep-change can take place

In the sensemaking-keywords overlay for SCAN, we use the keyword-set as a checklist to guide ways of looking at the overall system and its context:

- Simple: rotation – what perspectives are available from which to explore this context? how do we ensure appropriate balance of how we move between those perspectives?

- Simple: regulation – what mandatory rules apply? what arbitrary ‘rules’ do people seek to apply, and why? who benefits and/or loses from one-sided application of such ‘rules’?

- Complicated: reciprocation – how do the various factors and drivers balance up? if there is apparent asymmetry, what drives it? – and is it actually a real asymmetry, or only an apparent one because visibility of other counter-factors have become concealed?

- Complicated: resonance – what factors create feedback-loops, either positive or negative (damping)? in what ways does concealment of counter-balancing factors convert complex but natural ‘wild-problems‘ into much more destructive ‘wicked-problems’?

- Ambiguous: recursion – in what ways do the same patterns repeat in self-similar forms at different levels and in different contexts? if they seem only to occur at one level or in one context, what is it that constrains it to just that one context?

- Ambiguous: reflexion – in what ways can we see the whole within each or any one small part of that whole? what do differences between those views indicate about our understanding of the whole?

- Not-known: reframe – in what ways does our view change as we look at the context from different perspectives and through different frames? how can we use those differences to highlight elements that are otherwise hidden by ‘policy-based evidence’?

- Not-known: rich-randomness – how can we use serendipity, random-events, or deliberately ‘stepping outside of our comfort-zone’, to trigger fresh insights about the context?

Do beware that this kind of exploration can be fraught – to say the least! – with all manner of political dangers: there are a lot of vested-interests behind any form of ‘policy-based evidence’, and those ‘interested-parties’ may well react, sometimes to the extreme, if their pseudo-evidence is questioned, or their (our!) beliefs and prejudices are challenged in any way. Done carelessly, or done wrong, this can be a real career-killer, or worse: for each one of us, from a personal perspective, it’s probably one of the most difficult and dangerous parts of enterprise-architecture work that there is.

The catch is that this work must be done, if the enterprise and its architectures are to succeed, be effective, on-purpose – a fact which puts us, as enterprise-architects, on an often-unintended, yet inherently necessary, direct collision-course with a lot of people. It’s somewhat of a bleak joke that one definition of ‘stakeholder’ is ‘anyone who can wield a sharp stake in our direction’: we’re likely to discover here just how accurate that bleak joke really is… In practice, often the only thing that can make this in any way safe (or safer, at any rate) is to be fully open and transparent in all of the assessment, and in all of the reasoning that goes into it – because doing so leaves aggressive stakeholders where an attack on the reasoning would itself expose their own unfounded prejudices.

Note too that the challenges, and the tactics we need to employ, are essentially the same regardless of the source of ‘policy-based evidence’ and the resultant architectural-challenges that we need to resolve. Whether what we’re dealing with is vendor-hype, political guffleblub, gender-blame, ethnic-stereotypes, or simply some stakeholder arbitrarily pushing their own preferred ‘solution’ in a system-design, it’s all much of a muchness, all much the same type of architectural or governance challenge. The analysis, assessment, modelling and identification of ‘missing factors’ are all straightforward enough, for any competent enterprise-architect: it’s only the politics of it, and the emotional loading behind all of that, that make it all so fraught. Oh well…

Not easy – but it does need to be done.

Hope this helps, anyway.

And over to you for comment, of course.

0 Comments on “Beware of ‘policy-based evidence’”