Services and Enterprise Canvas review – 3D: Investors

What is a service-oriented architecture – particularly at a whole-of-enterprise scope? How do we describe the relationships between a service and and its investors and beneficiaries? Who or what are those respective stakeholders? And what happens within their respective service-interactions?

This is the final sub-section of the third in a six-part series on reviewing services and the Enterprise Canvas model-type:

- Core: what a service-oriented architecture is and does

- Supplier and customer: modelling inbound and outbound service-relationships

- Guidance-services: keeping the service on-track to need and purpose

- 3A: Direction

- 3B: Coordination

- 3C: Validation

- 3D: Investors and beneficiaries

- Layers: how we partition service-descriptions

- Service-content: looking inside the service ‘black-box’

- Exchanges: what passes between services, and why

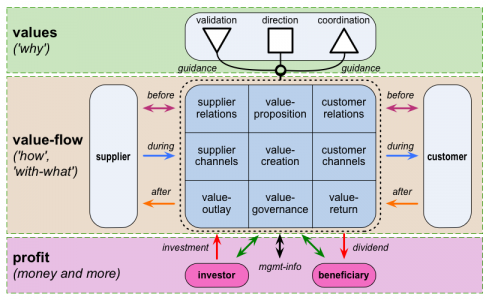

In the introduction to this part of the series, we saw how each service needs support from a variety of other services, to guide and validate its actions, and to coordinate its actions with other services, and its changes over time. We can summarise these relationships visually in the standard Enterprise Canvas model:

What we’re exploring in this post is that cluster of relationships that form the ‘feet’ of the Enterprise Canvas – the investors and beneficiaries.

By comparison with some of the guidance-services, this part is relatively simple. Simple, but not easy – that’s an important distinction here!

The simple bit is about what investors and beneficiaries are, and their core relationships with the service:

- investors provide some form of value (usually different from that which flows through the main ‘horizontal’ value-flow), in order to get the service started, or to maintain its operations in ways that cannot otherwise be provided by either the ‘horizontal’ value-flow, or the guidance-services

- beneficiaries receive some form of value (usually different from that which flows through the main ‘horizontal’ value-flow), as a dividend or benefit from the operation of the service, in ways that are distinct from either the ‘horizontal’ value-flow or exchanged with the guidance-services

Yeah, I know, it all sounds horribly abstract – though there is an important reason for all that abstract-stuff, as we’ll see in a moment. But to give the obvious example that everyone knows:

- as an investor, someone invests money in the company

- as a beneficiary, that person receives a dividend from the company

- there’s usually an expectation that that person will receive more money out than they put in – which is the reason for the investment

And yes, if we were to believe supposed economists such as Milton Friedman, that would indeed be the end of it: ‘making money’ for shareholders as the sole reason why any organisation exists. Except that, as mentioned in an earlier post, that concept, which, unfortunately, is still locked into most corporate law, is increasingly being decried by serious business-leaders as ‘the dumbest idea in the world‘ – and maybe even the most destructive idea in the world, too.

The key reason why it’s so dumb is because, to make an organisation (or any other type of service) viable, we need to take into account all of its stakeholders and stakeholder-groups – not some arbitrarily-selected subset such as the financial-shareholders. And there are a lot of those stakeholders: far more than most people, in business especially, seem to be able to image. Yet to find out who those stakeholders really are, here’s a simple test: a stakeholder is anyone who can wield a sharp-pointed stake in our direction!

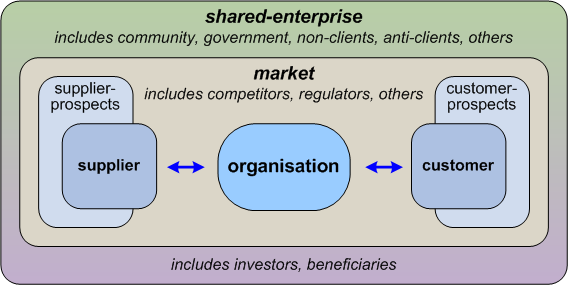

Which, again, is a lot. One way to get some idea of the scope is via the service-context model that describes the context for Enterprise Canvas. If ‘the organisation’ shown at the centre of this model is the service-in-focus, the service that we’re looking at at the moment, as the central service of our Enterprise Canvas, then the scope of the respective shared-enterprise – including all of its respective investors and beneficiaries – is around three steps further out than the nominal boundaries of the service itself:

Notice that the investors and beneficiaries typically come from the same place as all of those other people in the shared-enterprise who are not part of ‘the market’ – in other words, beyond the space that’s both source and destination for the main transaction-type value-flow of the service. Again, the people that most business-folks seem to think of as ‘the investors’ – the financial-investors, the so-called ‘owners’ – are just an arbitrary subset of the real stakeholders in the service and its enterprise. To understand how the service actually works, and design governance for how it actually works, we need to model a lot more of those stakeholders and their drivers, their needs, and their respective relationships with the enterprise, the service and each other. In theory, that’s every possible stakeholder: in practice impossible to do, of course – which is why we would turn, again, to the vision and values, of that shared-enterprise, to help us identify the effective real relative-priorities for different stakeholder-groups.

Perhaps the most important shift we can make here is to recognise that every organisation is ‘for-profit’: it’s just that we need a much broader concept of what ‘profit’ actually is. For example, parents and grandparents invest a great deal of time and energy in their children and grandchildren: there are real services involved there, and those investors do indeed expect real benefits from their investments in those services. Yet very little of that investment is in monetary form alone, and likewise for the benefits – more often in satisfaction, for example, or the joy of watching someone grow, find who they are, push the limits of what they can do.

(More to the point, if we do try to force interpretation of those investor/benefit relationships solely in terms of money alone, that attempt can, in itself, destroy the real desired benefit. As a simple test of this, go to your mother’s house for a key family occasion – a Thanksgiving dinner, perhaps – and, at the end of the meal, ask her for the bill, the check: what reaction do you get?)

A community or a government invests more than mere money in providing space and infrastructure for a company to do business: it invests its commitment, its trust, even some aspects of its own identity. And the expected benefits, yes, might well include corporate-taxes and business-taxes and sales-taxes and so on, and the secondary financial-revenue from employees’ income-tax and the like; but they’d also include perhaps-less-tangible yet equally important concerns such as community-health – in a wide variety of different senses of ‘health’ – and also community-spirit, community pride, and much more. Ignoring these other non-monetary forms of investment and dividend can cause individuals, communities, even whole countries, to become active anticlients of the organisation – a form of kurtosis-risk that can, and has, killed whole corporations, seemingly ‘without warning’.

Another perhaps more homely example: family. If you have family, then it’s probably self-evident that your family are beneficiaries of each organisation you work for, since, through their relations with you, they gain not just the various direct and indirect benefits from your having a financial-income, but also from your engagement in the work, satisfaction, purpose, pride in achievements both of your own and shared with others. Yet your family are also investors in each organisation you work for, in the sense that they support you in doing that work – particularly through purpose, identity, social-connection and more. Without their support in the background, their investment in you, day after day, you quite possibly wouldn’t be able to do the work that you do. So in that sense, the organisation is also an investor in your family, since it needs their support in order for you to be able to do your work within and for the organisation. A simple test: if your daughter, say, is ill, would you ignore her needs completely, and focus only on your organisation’s needs? The extent to which your daughter rises in your priorities for attention is also the extent to which the organisation needs to be an investor in the well-being of your family.

(If we follow the logic of this even a little bit further, we’ll see that, in effect, every stakeholder in a shared-enterprise is implicitly also a stakeholder in every other stakeholder for that enterprise. And yes, this one can go a long way down the rabbit-hole, if we’re not careful: we definitely need to apply here the Enterprise-Architect’s Mantra of ‘It Depends’ and ‘Just Enough Detail’…)

Which now brings us back to where we started, with the ‘feet’ of the Enterprise Canvas diagram:

From the above, what we’ve seen is as follows:

- investment takes many different forms – of which only one is monetary

- benefit or dividend takes many different forms – of which only one is monetary

- almost by definition, everyone who is associated with a shared-enterprise is also a stakeholder in that enterprise, and hence inherently both an investor in and beneficiary of that shared-enterprise

- the financial-shareholders or stockholders of an organisation represent merely one very small and very specific subset of the overall stakeholders of that organisation

In terms of Enterprise Canvas, investment is just another kind of value-flow – but sufficiently different from the main transactional ‘horizontal’ value-flow that we do need to handle it in a different way, with its own distinct channels and suchlike. (One obvious example of this type of distinction is the separate ‘Investor Relations’ section of many corporate websites.) In Enterprise Canvas, we show this value-flow as an ‘inwards’ arrow coming in towards the Value-Outlay cell, because financial-investors’ money typically goes onward to the service’s suppliers, so as to help set up what’s needed for the main transactional value-flow to start flowing – though in practice, of course, investment may in effect connect with any part of the respective service.

On the other ‘foot’ in Enterprise Canvas, dividend is also just another kind of value-flow that needs its own distinct channels and so on. In Enterprise Canvas, we show this value-flow as an ‘outwards’ arrow coming out from the Value-Return cell, because in effect the dividend is extracted from the inbound value-flow returning from the Customer.

Out at that most-abstract level, it all still looks fairly simple. Yet where it gets seriously complex, and seriously hard, is that:

- investments and dividends occur in many different value-forms

- the investors and the beneficiaries may or may not be the same people in each case

- the value-forms that come in may not be the same value-forms that go back out

- the value-forms that each investor provides may not be the same as that investor later receives – if at all – as dividend, or benefit

- all of the transforms and exchanges have to balance up somehow in a form that’s seen as ‘fair’ by all stakeholders – otherwise serious anticlient-impacts will result

In Enterprise Canvas, that juggling-act of monitoring and balancing all of the inputs, outputs, value-transforms and dividend-assignments forms a key part of the role and services that need to be provided by the Value-Governance cell – with the respective flows represented by the green double-arrows between Value-Governance and the ‘investor’ and ‘beneficiary’ roles. Note, though, that Value-Governance is unlikely to be able to do it all on its own: it’ll likely need help from the guidance-services – particularly Direction and Validation – to connect it to the shared-enterprise vision and values, and thence derive the guidelines and priorities that are needed so as to ensure that everything remains as ‘fair’ as possible and practicable. (Those guidelines and priorities also provide open and explicit basis for mediation, in the inevitable case where some stakeholder doesn’t think the balance is ‘fair’.)

The right way to do all of this is as per that Enterprise Canvas diagram above:

- we maintain clear distinctions between the ‘horizontal’ value-flow and the separate investment/dividend flows

- we include all stakeholders in consideration – not just financial investor/beneficiaries

- we include all value-forms in consideration – not just ‘money-as-the-only-form-value’

- we explicitly strive to create a fair balance between all of these, as guided by the overall shared-enterprise vision and values

(We’ll see more about value-forms and value-flows later in this series, in Part 5, ‘Service-content’ and Part 6, ‘Exchanges’.)

The fundamental driver for this is a really simple warning: always start from values, not money. If we focus too much on the money, we lose track of value; and if we focus too much on the ‘how’ of value’, we lose track of the ‘why’ that’s provided by the values. To make it work, we need to design our services and enterprise-architectures such that why comes before how – and for that matter, why comes before who. The reason why this is so important is that, without clear access to guidance from an overarching ‘why’, at every level, things will go wrong – which, if left unchecked and unanchored to why, will drive a downwards spiral into a seriously-dysfunctional and maybe even non-recoverable mess.

The wrong way to do all of this is, unfortunately, the kind of model that’s pretty much mandated in almost all current corporate law: money-first and manager-first, as in Taylorism and the like:

In effect, it flips the whole Enterprise Canvas upside-down and back-to-front, resulting in a structure that’s not so much simple as terrifyingly over-simplistic:

- financial-shareholders are deemed to be the exclusive ‘the owners’, the only relevant stakeholders (disenfranchising all others)

- money is deemed to be the only form and measure of value (explicitly and/or implicitly ignoring all others)

- the sole purpose of the organisation is declared to be ‘making money’ – or, as framed in “the world’s dumbest idea”, ‘maximising shareholder-value’

- executives and managers are agents of and report solely to the financial-investors, but are otherwise assigned absolute control and authority ‘over’ everything in the organisation

We know a lot of the reasons why this kind of ‘model of the firm’ was developed – perhaps primarily, in the case of Milton Friedman’s proselytising of ‘the dumbest idea in the world’, a quest to simplify the otherwise enormous complexities of value-governance for a potentially-infinite range of stakeholders. There’s also the point that money is easy to measure – despite too-often giving a comforting delusion of certainty and ‘control’ where none in fact exists. But the painful reality is that these notions inherently lead towards some truly horrible consequences for the organisation and its services, and its relationships with others in the shared-enterprise – such as:

- investment by non-financial stakeholders is still essential, but all of the benefits are required to be converted to monetary form, to be returned solely to the financial-investors – in effect ‘stealing’ all of non-financial investors’ investments, and thereby creating either huge disincentives to non-financial-investment, and/or ever-increasing anticlient pressures against the organisation

- with cost and revenue as the only metrics for control, almost the only available options for finding seemingly-real returns for financial-beneficiaries consist either of ‘over-price and under-pay’ in relations with customers and suppliers, or relentless cost-cutting, particularly of so-called ‘cost-centres’ – all of which tend to create brittle business-relations and increasingly-fragile infrastructures

- disconnection from vision or values leads to organisational-designs in which all of the guidance-service roles are subsumed into the past-oriented Value-Governance cell – leading to silo-bottlenecks (no independent Coordination), no real concept of future other than as a direct extension of the present (no access to Policy or Strategy, resulting in poor ability to cope with external or even internal change), and no means to apply value-metrics to ‘management’ itself (no independent Validation), leading the organisation wide-open to ethics-problems and worse

- disconnection from any vision or values other than money means that often the only available frame for Value-Proposition is on the basis of price or, at best, easily-copiable product-attributes – leading to a ‘race to the bottom’ with competitors

- lack of a Value-Proposition that could link with transaction-partners via ‘vertical’ connection through shared vision and values means that the organisation shuts itself out from any possibility of a ‘pull-marketing‘ business-model – instead forcing itself into costly, low-effectiveness and increasingly-unpopular ‘push-marketing’

The only way to avoid all of those consequences is to start from the values – not the money.

(A lot of people would say that this is ‘political’ – much too political for enterprise-architects to be involved in at all. And, yes, in many key senses, it is indeed very political – for example, any discussion about ‘fairness’, or about the primacy of money over everything else, is always going to be seen as ‘political’. But that doesn’t mean that enterprise-architects shouldn’t be involved – in fact it’s arguable that it’s even the main reason we should be involved. Remember that our role here is not as decision-makers, but as decision-support for decision-makers – and that distinction is important! Our job here is to lay out the real enterprise-context and its complexities – dispassionately and, as far as practicable, without our own politics – so that those who do have the authority to make those decisions do have the right information that they need in order to make those right decisions. Ultimately, everything we deal with as enterprise-architects is ‘political’ – and it helps everyone if we can indeed be open and honest about that!)

One final point: remember that all of this is fractal and recursive. Although the relations with investors and beneficiaries are easiest to see and model at the whole-organisation level, all of the above actually applies to every service, at every level of the organisation and beyond. For example, even in a money-centric business-model, we’d still expect to talk about the expected ROI – literally, Return On Investment – of even the smallest business-change. Unlike, say, Business Model Canvas, or a standard business process-model, Enterprise Canvas describes a pattern that we expect – in fact need – to find and confirm against with every type of service, at every level. There’s more detail on all of that, together with in-depth analysis and checklists, in the post ‘Enterprise Canvas as service-viability checklist‘.

Anyway, to summarise:

- every service, at every level, has its own investors and beneficiaries

- every stakeholder in the service and its overarching shared-enterprise is, by definition, both an investor and beneficiary in that service and enterprise

- investment and dividend may take many different forms of value – in effect, those as specified, required or implied by the shared-enterprise vision and its values

- investment and dividend are usually of different value-forms than those in the main transactional ‘horizontal’ value-flows, and also those of the ‘vertical’ vision and values

- investment and dividend usually enter and leave the service via different value-flows from those of ‘horizontal’ (transactional service-delivery) or ‘vertical’ (guidance) flows – don’t mix them up!

- value-flows from investment and activity will go through many different transforms – often non-linear, often non-transitive or non-reversible – before coming out as dividend

- investors and beneficiaries may well be different people

- explicit value-governance is required to manage all of these flows and transforms, to ensure that outcomes are considered ‘fair’ by all parties

- using money as the sole or primary business-driver, and ‘shareholder-value’ or suchlike as the sole or primary metric of success, will guarantee serious business-problems, and quite possibly complete business-failure – hence as enterprise-architects, we need to be able to explain, to decision-makers, how and why such business-designs are fatally-flawed, and how to instead develop designs that do work with and within a fully-viable shared-enterprise

We’ll stop there for now on the relationships of the core Enterprise Canvas, and move on in the next post to explore the concepts used to describe ‘layers of abstraction’ used for service-oriented modelling with Enterprise Canvas.

As usual, any comments or questions so far?

Hi Tom,

let me first say these are really good posts. I work in the public sector and I’m exploring options on how to best model, lets say education and childrens daycare services for example. One option would be to consider tax-payers and the city council as investors, as the council allocates (fixed, year in advance) tax-payers money to provide services. There is no monetary flow from customer after the transaction. They are also beneficiaries in the sense that they receive value from the main transaction (eg. being re-elected).

I’m also playing with the idea to model the children as beneficiaries and the childrens parents as customers. At least up until a certain age, when a person to a large extent is able to make informed decisions, it could make sense to model it this way.

No question from me really, just appreciating the fact that the canvas is very helpful in my current work.

Oh yeah, I do have a question after all. I know that the relationship is the asset, but how about when the “asset” being “worked” upon is a person (let’s say at the hairdresser or )? Where in the single-row extended-Zachman would this hairdresser customer go? If it is a relational asset, which relation are we looking at here?

/Anders

Many thanks on this, Anders! (And would love to know more about how you’re using the canvas, too… 🙂 )

And yes, very good point on “how about when the “asset” being “worked” upon is a person (let’s say at the hairdresser or )?” – a really useful challenge. I’ll use that as a worked-example when we look at service-content in Part 5 of the series.

Hi Anders – apologies that it’s taken a few days longer than intended, but the promised worked-example post is now up on the blog, as ‘Services and Enterprise Canvas review – worked example’: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2014/11/03/services-and-ecanvas-review-worked-example/

Hope it makes some degree of sense? 🙂

No problem, an easy-to-read and informative example, illustrating some of the things you’ve written about in this series. Thanks!

At the moment I’m using (part of) the EC within the IT dept at the city government. I’m helping them establishing a L0 vision and values to align to, which would function as an anchor for further work. There are a couple of interesting ways of thinking here. Although labeling it as ‘The vision’, the city government actually has several visions, ranging from having to do with education and elderly care to city construction and increasing employment in the city. After explaining the EC ideas around visioning to the CIO, he asks: “So, which vision should we choose then?”

This got me thinking – since we act within all these enterprises; should we constantly “switch” vision/values according to what task we’re working on at the moment? Probably difficult to enact at runtime, and probably comes with motivational issues as well.

Should we try to find a common enterprise that encompasses ALL of these enterprises? Maybe along the lines of “Trustworthy care of public matters”. Could be.. but maybe to vague. Also it seems kind of to artificially force many enterprises into one, where they would have best been treated as separate if it hadn’t been for the fact that the city government org decided to play a role in each of these.

Should we try to find a “narrower” vision that all of the IT departments infrastructural services can better relate to? Could make sense since eg server hosting and network services could be considered rather loosely coupled to educating kids. I wouldn’t expect a pen manufacturer to phrase their vision around one certain context where a pen is used. The same may apply to IT infrastructure services (although both of course have to pay close attention to who are using their services).

A narrower visioning for infrastructure services would imply that we also need to align to each of the specific enterprises mentioned above, when we are providing services that are more tightly coupled to those, eg process support system. Since the IT dept staff are few in numbers, I guess there’ll be alot of hat-switching in this scenario. Oh well.. At least the IT dept will have a clearer picture of the implications of organizing all these services in one org unit. I’m thinking a useful rule of thumb would be for one organizational unit to try to minimize the number of enterprises it engages in at the same time. Either by opting out of enterprises or partitioning org units differently. Would you agree?

A lot of rambling here, but it’s part of my mental process of trying to come up with a viable way forward. Anyways, that’s how I currently use (part of) the enterprise canvas. It would actually be interesting to hear your views on visioning for a “commodity”? Come to think of it, you already gave an example for this. At Zapamex they are in to making feet happy. Not making runners or lumber jacks happy (even if they make shoes for them as well). Maybe that’s sort of the same type of discussion?

One last question; do you think it would be advantageous to treat enterprises (in terms of visions) as if they were fractal? For example the enterprise of “making feet happy” is a part of the enterprise of “properly equipped runners”

/Anders