RBPEA: The dangers of ‘anything-centrism’

An architecture may have a centre – in fact most types of architecture work best if there’s a central theme or parti. Yet the process of architecting must not have a single centre – and that distinction is crucial, especially as we move out towards a RBPEA (Really-Big-Picture Enterprise-Architecture) scale.

So far in this series, we’ve mostly covered themes about essential content for or constraints on a large-scale sociotechnical architecture:

- RBPEA: Constraints and corollaries – core constraints that we can’t ignore at very large scales, such as the inherent impossibility of infinite growth on a finite planet

- RBPEA: Basics and fundamentals – on the necessity for the primacy of principles over ‘law’, and the huge hidden dangers of allowing paediarchy to run rampant

- RBPEA: Object, subject and ‘should’ – on two types of tactics worryingly common when paediarchy holds sway

- RBPEA: Feelings are facts – that we don’t have any choice about our feelings or beliefs, though we do have ‘response-ability’ about what we do about them

For this post, though, we need to explore how careless or premature framing of a context can itself impose artificial constraints on how we see or understand an architecture – misframings of the real context that, by definition, can make it almost impossible to develop a viable architecture for that context.

In reality, every real-world context has many, many interweaving threads and themes, but for this purpose, let’s simplify it right down to a straightforward interaction between just two themes – ‘black’ and ‘white’ – as illustrated by the classic Yin/Yang symbol:

Note that the relationship between the themes is dynamic, like a ball rolling along the road. Sometimes one theme is more prominent, then the other, changing all the time, and depending also on which way we see them.

Note that the relationship between the themes is balanced – sometimes one theme is more prominent, then the other, but there is an overall balance between them.

Note that the relationship between the themes is fractal – each theme contains within itself elements of the other, potentially onward to infinity.

Note that the relationship between the themes forms a system – dynamic, balanced, fractal, each element interdependent on the others, each element an ‘equal citizen’ with all of the others.

Yet note how easy it is to pick on one element as ‘the centre’ of the system, and downgrade or even ignore the importance of others. For example:

- a selective snapshot of a dynamic system will typically emphasise one element: if we then fall into the ‘policy-based evidence’ trap – Gooch’s Paradox, that ‘things not only have to be seen to be believed, but also have to be believed to be seen’ – then subsequent snapshots will tend to be taken at points which re-emphasise the apparent ‘priority’ of that one theme

- someone falls for the ‘statistics trap’: failing to understand that ‘high-probability’ does not mean ‘will always happen’, or that ‘low-probability’ does not mean ‘will never happen’

- someone has a personal preference for one theme, or a personal dislike of or antipathy towards another theme

- someone fails to understand the inherent fractal nature of most (all?) real-world systems – that each element also ‘contains’ every other element – and thence tries to force-fit every element into simplistic categories

These cognitive-bias errors (and many others like them) may be combined, of course – in fact sometimes we’ll see all of them happening all together within the one misframing of a context. The end-result, though, is that the context is misframed: one theme becomes viewed as ‘The Centre’, around which all others revolve.

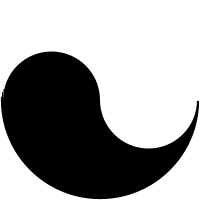

In many cases, attention is withdrawn so much from themes that are not ‘The Centre’ that they fade away from visibility, becoming ‘hidden in plain sight’:

When that happens, the system becomes literally unbalanced. Because it’s unbalanced – with more and more attention being placed on that one ‘The Centre’ – the system becomes more non-dynamic: it loses its ability to flow with the natural changes of its context, to ‘roll with the punches’ of change. And it also loses its ability to cope with nuance, with complexity, real-world uncertainty: increasingly, the system is reframed into ever-more-simplistic forms, often eventually into a crass ‘black and white’, with just one theme ‘good’, all others ‘bad’.

And because the system is unbalanced, there’s a very high risk that all other themes may become interpreted solely in terms of that one ‘The Centre’ – a situation I describe as a ‘term-hijack‘ – or even obscured entirely by the obsessive over-focus on the chosen ‘The Centre’:

When that happens, not only does the system cease to be dynamic, but every discussion is dragged back to that one ‘The Centre’. The result is that, to make the system work again as a viable system, we all but have to use a crowbar to get any attention paid to any other of the themes or threads within that context. Yet because of the need for such overt action, we’ll risk immediately being accused of being ‘anti-‘ the chosen ‘The Centre’, of ourselves being the ones who are ‘trying to make the system unbalanced’, ‘trying to destroy the system’, or whatever. Which is not a fun place for us to be…

In effect, what we’re facing here, as architects, is a classic paediarchy-problem: the two-year-old demanding to hold everyone’s attention solely on itself, and going into a possessive tantrum as soon as the attention shifts elsewhere, even for the briefest moment.

Which is understandable for a two-year-old, because at that age they still see themselves as the sole ‘The Centre Of The World’, and still have no real grasp of time – hence the sense that if something is lost, it will never return, and thence that their possession of that ‘something’ must be defended at all costs.

So yes, it’s understandable for two-year-olds – but not understandable, or defensible, from nominal adults working on real-world systems. That’s the crucial distinction we need to draw here: but unfortunately it’s a problem that is very, very, very common, almost everywhere in our so-dysfunctional cultures…

Practical implications for enterprise-architecture

As architects, we’re tasked with working on systems as whole-systems, so we’re likely to see far more of our fair share of this ‘anything-centrism’ problem. For example, within an organisation, every silo, every small fiefdom, will usually attempt to be or become ‘The Centre’ around which the architecture supposedly ‘must’ revolve. We need to become fierce defenders of overall balance – no matter how much we get accused of ‘betrayal’ and worse by all those relentless advocates of ‘our-thing-centrism’.

To make it worse, most existing ‘enterprise’-architecture frameworks are themselves riddled with some forms of ‘something-centrism’. I’ve warned about this problem quite often here, such as in these posts:

- How IT-centrism creeps into enterprise-architecture

- IT-centrism, business-centrism and business-architecture

- The dangers of specialism-trolls in enterprise-architecture

Probably the key source of ‘something-centrism’ in current ‘enterprise’-architecture is the dreaded BDAT-stack – ‘Business’, ‘Data’, ‘Applications’, ‘Technology’ – that all but forces us to interpret everything within the organisation in terms of its impact on ‘big-IT’. Increasingly, though, we’re also starting to see an equivalent over-emphasis on a similarly-mangled view of ‘business-architecture’, still ludicrously over-focussed on IT, yet ultimately based on an unacknowledged assumption that the only possible measure of value is money. In either case, Not A Good Idea…

The point here is that, whatever form the respective ‘anything-centrism’ may take, we must rigorously defend the architecture against any form of ‘anything-centrism’. To do that, we’re going to have to use that metaphoric crowbar a lot more often than we’d probably like – and probably a lot more than those around us would be willing to permit. Which means, in turn, that we need to wield that crowbar with a lot more subtlety than we might at first expect.

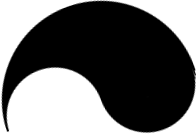

To illustrate where we need to put the metaphoric crowbar, take another look at that ‘term-hijack’ version of the Yin/Yang graphic:

It should be obvious from this that trying to tackle the respective ‘something-centrism’ from above is just not going to work – there’s too much mass there, too much resistance. (We’ve all fallen for that mistake from time to time, yes?)

Over to the right, there’s a lot of apparent gap, what looks an open space, an obvious place to tackle the respective ‘something-centrism’ – but if we try to tackle it there, all that will happen is that we’ll get squashed flat as it rolls over us with all of its mass behind it, and then rolls straight back to where it was in the first place. (Yep, I’ve done that one plenty too often too – been there, got the scars, lost the T-shirt…)

The way that does work is to tackle it at the left – some place close to ground-level that at first looks solid, but where gentle soundings indicate that it’s actually quite thin and brittle, and where the hidden-themes can be faintly heard somewhere not far beneath the surface. If we can find a point at ground-level there where there’s enough of a crack to allow some leverage, even quite a gentle push on the crowbar can open up enough of a gap to get some movement to start happening again – and the mass of the ‘something-centrism’ will likely also work with us in this, for a short while at least.

Once we do have a gap, we’ll need to keep it open, quickly, with a metaphoric scaffolding-pole or suchlike – otherwise, again, the mass of the ‘something-centrism’ will roll the gap closed.

If we can keep the gap open, we can continue to widen that gap with more scaffolding and more gentle pressure, until at some point the sheer mass of the ‘something-centrism’ will suddenly start to roll over all on its own. (Just make sure that there’s no-one underneath it over on the metaphoric righthand side when it does start to roll…) At the end of that roll – which can happen surprisingly fast, and can catch us unawares if we’re not watching for it – we’re back to the ‘hidden-in-plain-sight’ version of the context-view:

At this point we need to make sure that those other ‘hidden-in-plain-sight’ themes becomes fully visible, and stay that way. But because most of the attention is still being dragged down into that self-selected ‘The Centre’, the way to do this, somewhat paradoxically, is to focus at first on the same themes as those of ‘The Centre’, but in how they weave, fractally, through the ‘hidden’ themes as well. As we do this, we need to beware of the tendency for people to again reframe every theme solely in terms of their chosen ‘The Centre’ – which would drop us back into term-hijack again. Instead, emphasise the overall system, in terms of whole-as-whole, and the interdependency of all of its elements. Which, if we do it well, should bring everything back into dynamic, fractal balance again:

Dropping out of the metaphor and back to the real-world of enterprise, what are some practical tools that can identify that a term-hijack is taking place, and that can give us leverage to open the views again towards the dynamic balance that the system needs, that ‘everywhere and nowhere is ‘The Centre’, all at the same time‘? Some straightforward tactics that I’ve used to tackle IT-centrism, for example, include:

- What would the system look like if we moved the viewpoint all the way above this system, and came back down in a different place? (such as for user-experience elements in app-architectures, where we must focus on people first)

- What would the system look like if this ‘The Centre’ wasn’t there at all? (such as where existing IT becomes unavailable in a disaster-recovery context)

- What would the system look like if key elements of the system were reversed? (such as information in a kanban system, often intentionally maintained via physical cards rather than a computer-based app)

To give another example, one simple tactic I’ve used to tackle incipient-sexism in existing social-architectures is to invert any gender-pronouns: ‘he’ for ‘she’, ‘her’ for ‘him’ and so on. It can be kinda enlightening to see what that simple inversion shows us… – especially in contexts where there’s very deep term-hijack or stereotyping around certain gender-issues.

In a business-architecture context, viewing the organisation as ‘The Centre Of Everything’ is so endemic that it’s all but essential to do at least some assessment of what would happen in the broader shared-enterprise if the organisation was not there – a blunt but often effective way to break a habit of incipient organisation-centrism. It’s only if we do this that we start to gain some understanding of what the organisation actually does bring to the shared-enterprise table – and thence the real basis for its business-models and suchlike, viewed ‘outside-in’ as much as ‘inside-out’, in systematic modelling that maintains the overall balance throughout.

And in engineering-type contexts, probably the classic tactic for this is TRIZ, developed in Russia from the 1940s onwards as a systematic method for innovation and creative problem-solving. It provides a set of 40 principles for reframing a context – such as segmentation, ‘anti-weight’ or ‘the other way round’ (as illustrated by the inversion mentioned just above) – that can be cross-mapped to a set of 39 ‘contradictions’. Sometimes we might need to play a bit with analogies or metaphors to make it work, but overall it’s an essential item for any enterprise-architect’s toolkit.

The catch, of course, is that defence of ‘something-centrism’ is rarely rational, and the attacks on anyone who challenges the purported absolute-centrality of that chosen theme – even inadvertently – can be unpleasant, to say the least. One way I’ve found to reduce at least some of the attacks is to keep the focus on the big-picture, the broader-context, with a strong emphasis on what we’re for rather than what we’re ‘against’.

Also remember that, however much of a nuisance it may be, that arbitrarily-chosen ‘The Centre’ is still a valid part of the system – or we hope it would be, anyway. Hence another reminder that we do need to pay attention to that theme too at times, despite the very real need to keep pulling attention back to all the other themes as well. I remember one time when a group of architects expressed shock and amazement when I complained about the absence of detail about the IT-systems in their architecture: “But you’re the ‘anti-IT’ guy”, they said, “why would you want to know anything about that?”. “Not true”, I replied, “I’m not the ‘anti-IT’ guy, I’m ‘the system as a whole’ guy – and if your IT isn’t in that description of the whole, I want to know why!”

Tackling ‘anything-centrism’ is tough – probably some of the hardest and most challenging work that enterprise-architects ever have to do. But we really dare not shirk that work, because if any form of ‘something-centrism’ is allowed to take hold, the architecture will fail. Reason enough to take the challenge seriously, I’d hope?

Leave a Reply