Auftragstaktik and fingerspitzengefühl

Two words: auftragstaktik and fingerspitzengefühl. To an English speaker, they might look kinda weird, but they’re key to getting an enterprise to work well…

The terms originate from the German military, from around the early-19thC and mid-20thC respectively. They would translate approximately as:

- auftragstaktik – literally ‘mission tactics‘, though also now often combined with more strategic ‘commander’s intent‘

- fingerspitzengefühl – literally ‘fingertip-feel’, though conceptually more situational-awareness, an intuitive moment-by-moment sense and mental-map of the state and dynamics of the context-space

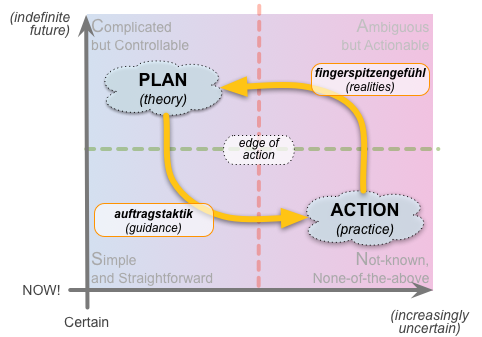

The crucial point here is to understand that they work as a dynamic pair, to provide a self-updating bridge between strategy, tactics and operations, or, more generally, between plan and action. In terms of the SCAN framework, we could map out the relationships between these elements as follows:

At the surface, all of this seems to be about information, which is then converted to commands:

Even though there is no physical connection between the commander and his troops, other than conduits for discursive information such as radio signals, it is as if the commander had their own sensitive presence in each spot.

Yet it’s not solely about information-flow. To illustrate this, let’s look at perhaps the most famous Second World War example of an auftragstaktik / fingerspitzengefuhl loop, which is not German, but British: the Dowding System used for the UK’s air-defence in the Battle of Britain and beyond.

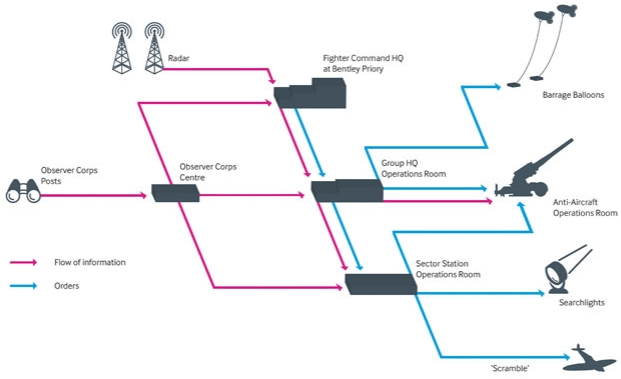

It’s one of the first instances of what would now be recognised as a ‘whole-of-enterprise’ architecture. First, information from radar and from observers on the ground (the ‘realities‘ for fingerspitzengefühl) is brought together into a central space for merging and interpretation.

The information is then filtered and simplified down into what we’d now describe as an ‘information-object’, representing a cluster of enemy aircraft, and its track over time (the dynamics for fingerspitzengefühl). In this example from a plotting-table, the red ’20’ represents the number of enemy-aircraft in the cluster, ’25’ represents the height (25000ft), and the yellow ’92’ and ’72’ are the identifiers for the defending fighter-squadrons assigned against them:

Yet an individual information-object, relevant though it would be, is just one element in the overall system. For example, the relationships between multiple information-objects give a much stronger idea of what’s going on in the context-space:

There’s also other information from other sources that needs to come into the picture, as seen in the boards in the background behind the plotting-table: squadron-readiness, fuel-levels and time-in-the-air, damage-reports, weather-dynamics and more.

And for their respective part of the overall story, the different stakeholders each develop their own interpretations – operational, tactical, strategic – from the picture developing on that dynamic map of the context-space:

All of those different views come together to form the plan, which then goes onward via the outbound-channels – such as the telephone-operators in the upper row in the picture above – as the auftragstaktik real-time guidance and intent for action.

As in this article from the UK’s Imperial War Museum, the relationship between information and command in the Dowding System is often depicted as a linear flow:

Yet describing the Dowding System in this way kinda misses the point – not least that there’s a lot of information coming back from each of the front-line units at the end of that supposed one-way flow. Instead, the key here is that auftragstaktik and fingerspitzengefühl provide a feedback-loop that – unlike classic top-down command-and-control – is able to respond to fast-paced change right down to local level.

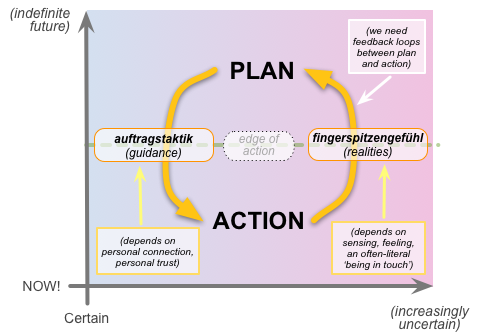

The linear-flow description also misses the point that it depends on more than information alone – there are key human elements without which the auftragstaktik / fingerspitzengefühl loop risk fading away into nothingness. For example, auftragstaktik is deeply dependent on trust, which in turn depends on a sense of personal connection and personal, mutual commitment, whilst fingerspitzengefühl depends on a more emotive form of sensing, of feeling, of an often-literal sense of ‘being in touch‘ with what’s going on out there in the real-world:

In the Dowding System, for example, Dowding and the other commanders went to considerable effort to build in-person connections with flight-crews, maintenance-managers, radar-crews and all of the other players in the overall context. This not only builds trust, but a better sense of the extent of who and how to trust, such as the trustworthiness of information – a key concern in present-day social-media monitoring, for example.

(Not just trust, but other emotive elements too. Maintaining morale and commitment can be a huge challenge when, as in the context of the Dowding System, staff could well necessarily hear, over the air, their colleagues, friends, loved-ones, in combat, challenged, stressed, fearful, wounded, even dying, in real-time, moment-to-moment – sharing the stress but being unable themselves to do anything about it. Yet it’s not just a military concern from a past war: much the same still happens every day in every civilian emergency-services ops-room or call-centre, everywhere around the world. Helping staff to manage the stress and survivor-guilt is a key business-challenge in these contexts.)

A related concern on the fingerspitzengefühl side of the loop is around how filtering of raw-data into structured-data forms tends to give rise to ‘information with the crusts cut off‘ – an over-simplification in which key information ‘at the edge’ gets lost, and from which inappropriate decisions may be derived. This is usually less of a problem when the scale of the enterprise is small, because the personal-relationships enable errors and misinterpretations to be corrected quickly. We still need to be wary of ‘groupthink’ and other forms of cognitive bias, but otherwise that kind of correction happens naturally for an individual or a classic ‘two-pizza team‘, and often implicitly up to the social-network limit of the Dunbar Number, or, in effect, the scale of a team of two-pizza teams.

Beyond that scale, though, we need to make deliberate and explicit efforts to maintain the non-structured aspects of the loop. Even at a three-tier scale, a ‘team of teams’, there’s a risk that people in the middle will start to lose contact with reality at either end of the loop – the plan, or the action. And once we get anywhere up to or above the five-tier scale – a theoretical maximum of around 124, or an organisation-size of around 20,000 (though often much less) – then there are huge risks that a combination of misplaced ‘top-down’ delusions and an absence of ‘crusty’ information from the real-world will result in a major disconnect in the middle layers of management. Those managers may, all too literally, be living in an imaginary world, based on garbled orders and over-filtered information, with little or no connection to business-reality at all. This is well-illustrated in a quote from a Foreign Policy article on auftragstaktik:

The other main reason for the defeat of the Wehrmacht [was] the sheer boundless arrogance of its officer corps. Being for so long the most famous and prominent group in a nation and admired by their countrymen and international observers alike left its pathological marks. The result became “a persistent tendency of most German Generals to underestimate the size and the quality of the opposing forces.” […]

All those immense flaws of the Wehrmacht senior officers counterbalanced the excellence in command, tactics and leadership German officers displayed in World War II. The latter explains why the German army was such an outstanding fighting force on the tactical level but still unable to win the war.

In short, breaking the continuity and integrity of the auftragstaktik / fingerspitzengefühl loop is Not A Good Idea…

There are ways to do this right. For example, there are practical tactics such as ‘conversational leadership‘ (PDF), that not only develop the trust to support auftragstaktik, but also help to elicit the subtler information needed for full fingerspitzengefühl. In military contexts, there are often deliberate rituals to rebalance top-down management-architectures, to enhance opportunities for person-to-person connections across an overall unit, and to emphasise a sense that ‘everyone has different roles, yet everyone is equally important’. These days we also see concepts such as design-thinking – in effect, further variants on the auftragstaktik / fingerspitzengefühl loop – formally embedded in military operational-doctrine and the like.

Another key element is organisational-culture – whether the culture invites or dissuades individual judgement within real-time action (auftragstaktik), elicitation and capture of real-world subtleties (for fingerspitzengefühl) and/or whistleblower-type algedonic responses. There’s a great illustration of this in Atul Gawande’s book The Checklist Manifesto., about Wal-Mart’s response to the Hurricane Katrina disaster in New Orleans. First, there’s the autragstaktik side of the loop:

Briefed on what was developing, the giant discount retailer’s chief executive officer, Lee Scott, issued a simple edict. “This company will respond to the level of this disaster”, he was remembered to have said in a meeting with his upper management. “A lot of you are going to have to make decisions above your level. Make the best decisions that you can with the information that’s available to you at the time, and above all, do the right thing”.

As one of the officers at the meeting later recalled, “That was it.” The edict was passed down to store managers and set the tone for how people were expected to react.

And, more on the fingerspitzengefühl side:

In other words, to handle this complex situation, [senior Wal-Mart officials] did not issue instructions. Conditions were too unpredictable and constantly changing. They worked on making sure people talked. […] The team also opened a twenty-four-hour call-center for employees, which started with eight operators, but rapidly expanded to eighty to cope with the load.

Along the way, the team discovered that, given common goals to do what they could to help and to coordinate with each other, Wal-Mart’s employees were able to fashion some extraordinary solutions.

Again, the crucial point here is that the culture overtly supports the auftragstaktik / fingerspitzengefühl loop:

The assistant manager of a Wal-Mart store engulfed by a thirty-foot storm-surge ran a bulldozer through the store, loaded it with any items she could salvage, and gave them all away in the parking lot. When a local hospital told her it was running short of drugs, she went back in and broke into the store’s pharmacy – and was lauded by upper management for it.

Okay, that was in context of a major emergency, and under more ‘normal’ conditions the response from upper-management would no doubt have been very different! Yet executives and senior-managers can also “set the tone” for a more everyday auftragstaktik and fingerspitzengefühl in other ways – particularly by personal example. This is probably best typified by Herb Kelleher, former CEO of Southwest Airlines in the US, who apparently spent at least one week of each month working on the front-line, as cabin-crew, on check-in and gate-management, and in baggage-handling. The ways in which principles underpin the auftragstaktik / fingerspitzengefühl loop, to provide deeper guidance in the face of the new or the ‘Not-known‘, are also illustrated well in some of Kelleher’s quotes:

“We have a strategic plan. It’s called doing things.”

“When someone comes to me with a cost saving idea, I don’t immediately jump up and say yes. I ask: what’s the effect on the customer?”

“If the employees come first, then they’re happy. A motivated employee treats the customer well. The customer is happy so they keep coming back, which pleases the shareholders. It’s not one of the enduring great mysteries of all time, it is just the way it works.”

“A company is stronger if it is bound by love rather than by fear.”

Another example of exemplifying a cultural principle was Kelleher’s method for resolving an inadvertent yet potentially major trademark-dispute. Instead of spending perhaps millions on litigation, he got together with the existing trademark-holder, and between them they turned the whole contest instead into a charity fund-raiser, built around a person-to-person arm-wrestling match – a comedic media-event nicknamed ‘Malice in Dallas‘. With a fingerspitzengefühl awareness of the fine-detail of the context, and with a principles-based auftragstaktik emphasis on the overall aim rather than the specific means to be used to get there, then in complex contexts there’s always another, better way to achieve the same outcome: that’s really the point to be noted here.

If you want more on this, the link between auftragstaktik and fingerspitzengefühl was a key theme in my slidedeck ‘Invisible Armies: information, purpose and the real enterprise‘, this-year’s session for my regular end-of-conference ‘Gravesyard Slot’ at the Integrated-EA conference, back in early March. I forgot to publish the slidedeck on this blog at that time, so here it is, for general delectation, delight or whatever:

Share And Enjoy, perhaps? I hope it’s useful, anyway, and over to you for comment, if you wish.

0 Comments on “Auftragstaktik and fingerspitzengefühl”