Enterprise-architecture – it’s about (much) more than just IT

Enterprise-architecture – what is it?

There are so many arguments about this – especially on LinkedIn – that it’s easiest to sidestep the question, and say that enterprise-architecture is the architecture of the enterprise. Kinda straightforward, when we look at it like that.

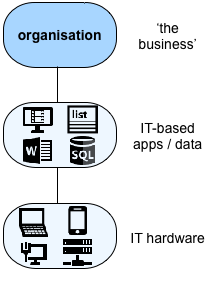

But in which case, what is ‘the enterprise’ to which an enterprise-architecture would apply? If we look at most so-called ‘enterprise’-architecture frameworks, this is how they’d describe it:

Which no doubt makes sense if the only thing we ever work with is some aspect of IT. And yes, to such of us who work that way, it can well seem that IT is far more than just one more type of enabler – it’s the centre of everything!

The assumption is seems to be that “Ubiquitous IT having captured domains in entirety” – to quote Vance K. Saxbe on LinkedIn – and hence, he says, “it is wise to define EA as Strategy to IT”.

Short answer to that assertion? No.

Just no.

Would we describe the enterprise of a restaurant solely in terms of IT?

No.

Just no.

To be blunt, it is really, really unwise to define enterprise-architecture in that way.

Still far too common, sadly, but still deeply unwise.

An over-focus on IT is perhaps the most common error in enterprise-architecture – and until architects learn how to keep IT in proper context and perspective in their understanding of enterprise, it’s perhaps also one of the most dangerous and destructive errors in EA, too.

Making that paradigm-shift still seems to be absurdly difficult for many EA-folks – I don’t know why. But until they/we do make that shift, they/we remain, at best, mere IT-architects – not enterprise-architects, literal ‘architects of the enterprise’. And that distinction is utterly crucial for the development of this discipline.

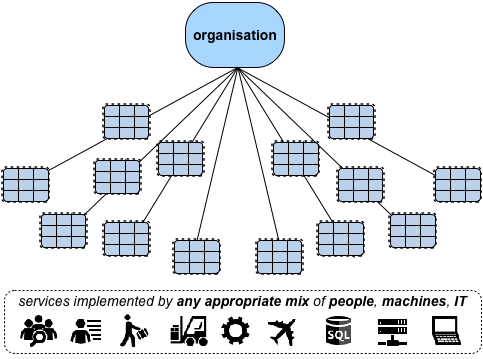

Yes, in most organisations now, IT is deeply interwoven throughout the enterprise – but so is everything else. The reality is that the organisation’s business-model and business-operations consist of a bunch of services implemented by any appropriate mix of people, machines and IT, and supported by any appropriate mix of facilities, assets, resources and more:

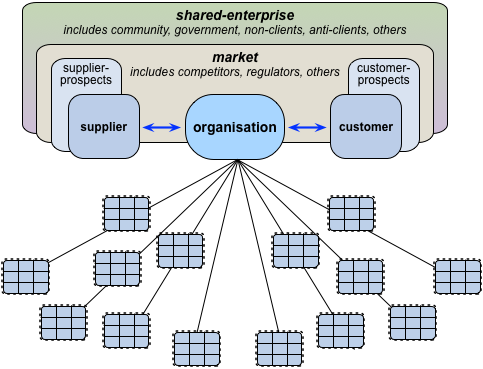

It’s also worth remembering that, literally, ‘enterprise’ is ‘a bold endeavour’. That’s a primarily human characteristic: I’ve yet to see any IT-system that is either bold, or endeavouring… And once we look at the enterprise, not just as the organisation itself, but as a human construct, then a much, much broader and, yes, more human context emerges:

The extent of IT-centrism in most so-called ‘enterprise’-architecture frameworks at present is frankly absurd. In TOGAF, for example, the description of their supposed ‘business-architecture’ is, in essence little more than ‘anything not-IT that might affect IT’. Which is kinda parochial, if not just plain stupid, once we realise that the real enterprise looks something more like that graphic above.

Yes, sure, IT is relevant there, in fact often quite important. No doubt about that.

But IT as the sole centre of everything, around which the entire enterprise revolves? Not so much…

If we look at end-to-end business-processes, they’ll be made up of any appropriate mix of people, machines and IT: and in many cases the IT might well play only a small part – if any at all. So should we always centre every exploration around IT? What about everything else? Isn’t that sometimes (a lot) more central than the IT?

If we compare to organisational spend, IT typically accounts for no more than 5% of the total budget. But what about everything else, in the architecture of the enterprise? Isn’t that too also important to the overall architecture?

As supposed ‘enterprise’-architects, just how much attention do we each pay to that ‘everything else’, by comparison with how much attention we pay to the IT?

Do we even know what that ‘everything else’ is?

Do we know and understand how all of the enterprise fits together, works together?

Yes, IT is an often-useful enabler in the enterprise: but do also we recognise how, if its limitations are not understood, IT can easily become a disabler for the enterprise? Do we understand enough about how damage an over-focus on IT can cause?

“I wasn’t smart enough about that [the strict focus on efficiency and technology and the disregard of people in the organisation that is subjected to a reengineering initiative]. I was reflecting my engineering background and was insufficient[ly] appreciative of the human dimension. I’ve learned that’s critical.” — Michael Hammer

Let’s be blunt about this: Until we do understand this, and keep a proper balance between the IT and the ‘everything else’ in our architectures, we cannot and should not describe ourselves as enterprise-architects.

And, as Mark Paauwe warns:

An architect is a total concept designer and supervisor of the realization of structures with that total concept. And enterprise architects are only enterprise architects when they design total enterprise concepts (or parts of it) and supervise the realization of enterprise structures (or parts of it) using that total concept (or parts of it).

The crucial addendum is that the ‘(or parts of it)’ must always be in context of the whole. The problem with IT-centrism is that it purports that its (quite small) part is the whole, and that nothing else matters, or even exists. Architecturally, that is definitely Not A Good Idea…

In practice, then, we need an enterprise-architecture that is careful to keep technology in its place, as an enabler rather than an arbitrarily-overemphasised deus-ex-machina. To avoid making the kind of complete shambles that is depressingly common when IT-obsessives get involved in enterprise-architecture, we need to break free of the myopic delusions of enterprise-seen-as-IT, and instead, in enterprise-architecture, keep the focus first and foremost on the needs of the enterprise-as-enterprise.

We forget that focus at our peril.

IT is just a “qualification” test for enterprise architects 🙂

Thanks,

AS

Over-focus on IT is detrimental to software architecture…the idea that Enterprise Architecture is “all about the IT” is just ludicrous.

Imagine someone making the argument that surgery was “all about the cutting” because every surgeon has to know how to cut. On an extremely shallow level, that’s correct. However, knowing what to cut, when to cut, and why to cut are much more important. Most important of all, is being able to work with the patient to figure out whether a surgical intervention makes sense for them (the proverbial cure being worse than the disease). You can (and some have) automate the cutting technique. The knowledge part is a way more wicked problem, primarily because it transcends the narrow focus of just the surgeon.

Those of us who rail about the need for enterprise architecture to be enterprise-centric, and that enterprise itself is a people-centric concept, often overlook the fact that enterprise architecture is itself an enterprise, i.e., a “bold endeavor”. As such, it too is people-centric. And as such, it is unfortunately the case that the EA community gets to define, in a very real sense, what it means by enterprise architecture, no matter how offensive that definition might be to the small minority of us that disagree with the community as a whole.

Acknowledging this fact is not to concede defeat and accept the community’s flawed (in our opinion) conceptualization. But it does suggest that changing the community’s way of thinking about enterprise architecture is likely to require more than standing on a virtual soapbox and repeatedly shouting at them that they are wrong. Appealing to sensible linguistic interpretations or a logical epistemological foundation for the discipline isn’t working.

They’re just not listening. They don’t need to. We’re shouting at ourselves. In the mean time they go about their business giving their sponsors what their sponsors are asking for, earning a living doing so, while at the same time the business architecture, design thinking and enterprise design communities are working a different audience.

Blaming The Open Group and TOGAF doesn’t help either. TOGAF is a symptom, not a cause. The reason TOGAF is the way it is and The Open Group is as successful as it is are entirely a matter of their reading their audience correctly. They’ve done exactly what we insist architects do – listen to their stakeholders.

What does our “correct” concept of enterprise architecture tell us about how to effect the enterprise transformation that we so fervently believe is necessary – changing the way the enterprise architecture community thinks about enterprise architecture to a truly whole of enterprise, people-centric concept. And can we possibly do this without engaging with the business architecture, design thinking and enterprise design communities?

len.

Len – well put! A clear challenge! And time that the challenge was taken up!

Using TOGAF as a reference point, we might well ask:

a) who are our key stakeholders, customers, audience? If we don’t understand our customers / audience, we will never have the right products, services, story

b) what are our key products and services for these customers?

c) what is the value proposition(s) for our products and services? what problem are we helping our customers solve?

I see three distinct customer segments:

i) Boards / Directors

ii) CEO / Executives / Managers

iii) Other change professionals (OD, QM, etc)

I wonder what problems EAs think these groups have?

I wonder what value proposition EAs offer through their products and services to these groups?

This is very interesting, Peter, when you say:

“I see three distinct customer segments:

i) Boards / Directors

ii) CEO / Executives / Managers

iii) Other change professionals (OD, QM, etc)”

Historically, and even today, I would say this is at most aspirational. Historically the clients for EA have been IT development shops and IT procurement organizations. I spoke about that historical heritage in my post on the hairball, and pointed in a more aspirational direction in my posts about 12 value propositions, and 23 questions EA should be able to answer.

This is why, in a discussion of one of your postings I tried to make the point that if EA does an excellent job of managing the IT portfolio, it will necessarily have to capture an architectural perspective on the enterprise as a whole, where IT is a systemic (nervous system) component or subsystem.

This means that for EA to do a great job with IT, it will have to deal with Tom’s “(much) more than just IT” condition, and where it doesn’t capture much more than IT it will do a not-so-great job, and in fact a pretty lousy job.

Interesting point Doug.

I think the ramifications of Len’s, Peter’s and possibly Tom’s post may be that if “true EA” is in fact “whole of enterprise” as Tom suggests, then the customers for EA of this kind are different than the historical customers… And it may be that they won’t buy EA unless it is repackaged to solve their enterprise problems in language they understand.

In other words, EA in Tom’s sense is not only enterprise centric in function, but also in sponsorship.

Just to clarify my thought: it seems to me that Tom is not suggesting that the discipline of EA be primarily responsible for the management of IT development (but with a holistic view of the enterprise), but rather that EA be responsible for supporting the management of enterprise development across business, organizational, and technical domains.