Making enterprise-architecture more tangible

Enterprise-architecture: it’s kinda abstract, isn’t it, most of the time? All those techie diagrams and so on, that only a techie would love…?

Which may be one reason why it’s been so hard to get traction for EA outside of the technical domains in an enterprise.

Yet what can we do about that?

Seems to me that we need to rethink enterprise-architecture quite a lot. For example, more in terms of the other dictionary-definition of ‘enterprise’: not merely enterprise as ‘a commercial business’, but the more inclusive, more expansive, more human-oriented ‘enterprise as a bold endeavour‘.

Which suggests that, by that definition, EA should be mostly about people – not machines.

Machines play their part, of course – always useful as support, and these days all-but-essential as enablers. No doubt about that. But I’ve never seen a computer that’s either bold, or endeavouring, towards some self-chosen purpose greater than itself.

In which case, making out that EA should be mostly about machines – as many folks still do – is kinda missing the point…

Which in turn means that we need to reframe our enterprise-architectures more in terms of people.

And maybe reframe ‘people, process, technology’ into a more human, narrative-oriented form, as ‘actor, scene, stage‘ and suchlike.

We also need to make EA more tangible.

I’m immediately reminded here of a CIO for a government department in the social arena. She’d struggled for a long while to get her executive to understand why their IT-systems were structured the way that they were. But she was a keen amateur woodworker: so she created the systems-model as a multi-layer jigsaw-puzzle – with the security-layer, for example, as a literal, physical, tangible layer of the model. And yes, now the systems-model did make sense to her executive!

Yet we can create tangibility in simpler ways too. For example, here’s a little aide-memoire we used within a large logistics organisation:

Within an architecture, there are four key dimensions that we need to keep track of at all times: physical stuff, virtual information, relations between people, and aspirational motivations such as enterprise-purpose, brands and more. In practice, it’s hard to keep track even of three of those themes at a time – a single face on that tetrahedron. But in the middle of each face is a reminder of the ‘missing’ theme – and if we rotate the tetrahedron, other faces in turn come into view, reminding us of the whole-as-whole. Architecture made tangible…

Even that tetrahedron-model is a bit abstract, though. Let’s take it a step further, more into the people-realm…

(If what follows sounds a bit like ‘play’, it’s because it is. Don’t worry: there are plenty of long-established usages of ‘serious play‘ in business. But if you’re still worried anyway, note that other words for ‘play’ might include ‘modelling’, ‘simulation’ and ‘experiment’ – all of which are definitely important for enterprise-architecture, and much, much more!)

For example, who is the architect? What does an architect do?

What’s on the enterprise-architect’s desk? What’s on the plan? What is the model that’s being built? What documents and other items – a laptop and more – might be there inside that briefcase? Why? What are the enterprise-architect’s tools – this discipline’s equivalents of the ruler, the set-square, the dividers?

And why might an enterprise-architect need a hard hat? Against what hazards of the trade…?

Useful questions, useful explorations – and made much easier to explore, just by having that mini-figure to play with, to demonstrate, to explain, to move around.

Let’s take it a step further, to explore interactions between ‘actors’, in service-design and suchlike. Here’s another set of mini-figures, bought over the counter in a toy-store:

(That set also includes mini-figures of a police-officer, a firefighter, a doctor and nurse – all of them useful as metaphors in business!)

Move the figures around, place them in relation to each other, describe that relationship in terms of story:

In this example, with the enterprise-architecture team of a city-government, one of the participants placed the police-officer figure as representing the security-checks for a bank. In front of that mini-figure was another that, for him, represented a potential customer for the bank. It was important, he said, that the security-checker could gather together all the bank’s information on that person – the ‘single view of customer’, even for a person wasn’t yet an actual customer. Some useful and practical discussions arose from that, about how to bridge the organisation’s information-silos, and so on.

But we then switched the view around – literally so, looking at the scene from the other side of the table. Now we looked at things from the potential-customer’s perspective – in effect, a shift from ‘inside-out’ to ‘outside-in’. Where now was the ‘single view of supplier’, that that customer would need? In most cases, it’s a mess, often to the absurd extent that (in this example) the would-be customer needs to know more about the internal workings of the bank than the bank knows about itself – just to get any sense out of the bank at all. Which is perhaps not good news for a bank that wants to acquire and keep new customers – yet should definitely be of concern to its architects!

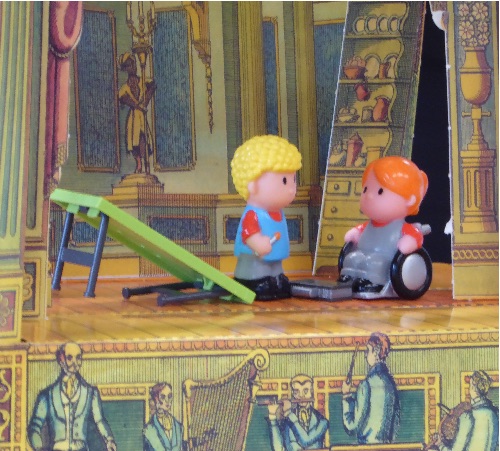

The next step was to put on a show – literally, using a cardboard-model ‘toy-theatre’ – to describe the actors, scenes and stage for a proposed service-design. In the example here, the service-design was about mapping out how the city would respond to potholes and other road-maintenance problems, particularly those that caused minor injuries, yet would otherwise go unreported as an increasing risk. Participants in the session described the flow and actions of each scenario in the service-model, using the mini-figures and the available props – the part-collapsed desk here representing a crashed bicycle:

Working through the steps of the scenario, all manner of other questions would – and did – arise. What information and infrastructure did each actor need? How would they access that information and suchlike? Would a mobile-app help? If so, where would that information come from, and how would it be accessed under the conditions of the scenario? How would each actor react to other players? What would be needed to build and maintain trust between each of the players? What would help or hinder the service-flow, moving towards the story’s intended conclusion – the satisfaction of each player’s needs? A lot of really useful insights will arise from this kind of roleplay-by-proxy.

Yet we can take this one step further again, assessing the action on the stage – the core service-design – within its broader context:

This elicits further questions such as:

- What’s going on behind the stage? If the scenario calls for information, what is the infrastructure through which that information would be made available? How would it all work? Is the infrastructure fit-for-purpose for that need?

- Who is the audience, in front of the stage? Given that they’re the ones who are likely to be paying for the story to reach its end, what are their concerns, their drivers? How we achieve satisfaction not just in terms of the story on the stage, but for each member of the audience too?

- Who’s managing the theatre in which this story happens? How does it advertise its wares, celebrate its successes, keep everyone happy both within and beyond the theatre?

- What’s going on around the theatre, in the wider world? How does it connect with other theatres, the whole community of theatres, the broader community itself – even with those anticlients who object to theatres’ existence at all?

Try doing that with a conventional ‘EA-toolset’, or any mainstream ‘EA-framework’? We’ll soon discover that most of what we’d need, to explore or describe those themes, just isn’t there at all – but without that exploration, we’d be ignoring huge hidden risks in business-model design. Not A Good Idea…

The moral of this story? Finding ways to make the enterprise-architecture more human-oriented, and more tangible, will bring big dividends, in terms of understanding, insights, acceptability and more.

Over to you for The Next Thrilling Instalment in this enterprise-story:

— How will you help your architecture-stakeholders to get in touch – literally – with your enterprise-architecture?

Watch This Space, perhaps?

Tom

This is a really excellent post. You made my morning commute! I have been thinking about people and EA for years now and like your approach. I will be in touch. I have the opportunity to try this in my new role at the City of Vancouver. All the best! Leo

Many thanks, Leo! – and yes, please do keep in touch.

If you want to play with these yourself, one of the great points is that the equipment is all in the low-cost range 🙂 The mini-figures I used were from Playmobil (the architect) and Early Learning Centre (all of the others) – the whole lot cost about £15 (c.CA$25?). Lego mini-figure knock-offs can be even less – I’ve seen a pack of fifty for less and $5. (The official Lego mini-figures are fiendishly-expensive, though…) The toy-theatre came from Pollocks Toy Museum (see the link in the article above), and here in Britain was only £17. It might be almost twice that much after mail-costs etc, but even so that’s pretty much in the consumable-item range for a training-gig.

I’ll be happy to talk you through how to do this, the various tips-and-tricks I’ve learnt whilst doing it – though if the City of Vancouver can afford to fly me over to do it with you, you know where I is! 🙂 (It links really well with SCORE, SCAN and Enterprise Canvas for a full strategy-to-execution pathway, by the way.)

Nice post Tom – I’m tucking this one away for future reference.

If I get a chance to use it I will be sure to let you know how it went.

Many thanks, Ric – would love to know how it goes!