Architecting the shadows

In enterprise-architecture, we’ve long known about the importance of shadow-IT – the place where much of business IT-innovation comes from, yet also presents organisational risks if not managed appropriately.

Yet whilst talking with Pierre [I never did catch his surname – apologies…] at my workshop at the Irish Computer Society a few days ago, the conversation shifted to the relationship between ‘fintech’ (financial-technology) startups and the insurance companies that acquire them – and from somewhere between us, up came the idea of shadow-business-model. In essence it’s much the same as shadow-IT – a place where innovation can happen – but this case the ‘hands-off’ relationship allows the acquirer to experiment with business-models, separate from many of the reputational, regulatory and other constraints that would and should apply to the organisation’s main business-model.

(Another classic example was Amazon‘s acquisition of Zappos – companies with very different cultures and related yet very different business- and operating-models, but where a careful ‘hands-off’ relationship can allow each to learn from the other.)

Then there’s that long thread-conversation in Peter Murchland‘s post ‘What are we missing?‘, in the Enterprise Modeling group on LinkedIn. In one of the comments, Allen Woods notes that:

One of the more curious things about serving in an infantry battalion is that while there is a command structure that is assiduously obeyed, there is one institution, the warrant officers and sergeants mess, in which “ad hoc” business is planned and executed outside of the formal command chain on a daily basis. Nothing illegal, just agreements between like minded individuals who share, roughly, the same social status….

There’s then a wry aside from Mark Goetsch, that “According to Max Weber, who based his organizational ideas off the Bismark based war machine, such things should never exist…”. But Allen Woods continues:

Ah but they do… Even in Bismark’s Prussian army and not just in the military. Another curious thing is that the although the messes do not form part of the command structure, they have their own management hierarchy and internal traditions and processes.

Incidentally, it’s that kind of organisational entity that I don’t think the current crop of EA tools and techniques can deal with… But they really ought to.

As it happens, I’ve been thinking a lot recently about shadow-IT and shadow-business-models, and their importance to enterprise-architectures. From that, it seems to me that what Allen is describing re the NCOs-mess is shadow-management – and with a similar ‘get the job done’ relationship to the ‘official’ management-hierarchy as shadow-IT has to ‘official’-IT. And yes, it does get the job done, correcting the real-world gaps in the often too-theory-based ‘official’ plan, and suchlike.

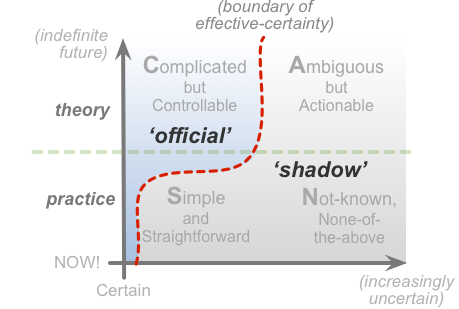

In SCAN terms, we could summarise the generic positioning of all ‘shadow’ functions – shadow-IT, shadow-business-models, shadow-management and more – much as follows:

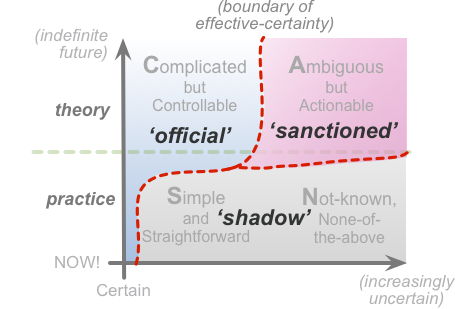

In other words, the ‘shadow’-world exists to deal with and resolve all the uncertainties and over-simplifications that overly-mechanistic management models tend to overlook. Even in more aware management-models, in which some exploration of the uncertain is officially sanctioned and allowed, the shadow-world will still always need to exist – particularly whenever the work gets closer towards real-time action:

From an enterprise-architecture viewpoint, the ‘shadow’-world needs that separation from the ‘official channels’ in order to do its job properly – that’s the point that’s easy to miss. The shadow-elements deal with the parts of the context (and its architecture) that the ‘official channels’ can’t address, because those ‘official channels’ can, by definition, only deal with a world of certainti – or a mostly-certain world, anyway. For example, by definition, innovation can only occur with something that’s not-known, beyond the rules, literally anarchic. If we try to force the ‘shadow’-elements to be ‘under control’, or bring them all ‘out into the daylight’ or whatever, we defeat the whole object of the exercise. Instead, it’s best to think more in terms of a spectrum of ‘governance-of-governance’ – and the ‘shadow’-elements need to be right out at the far end of that spectrum, under a much looser form of governance.

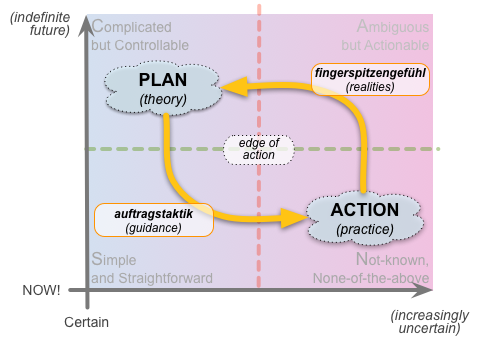

The danger or risk, of course – as can be seen so easily with misuse of shadow-IT – is if there can too easily be a disconnect from or to the big-picture strategy. Hence the importance of commanders’-intent and suchlike – to provide the core guidance within that looser form of governance – and also the auftragstaktik / fingerspitzengefühl feedback-loop that helps maintain situational-awareness under turbulent change:

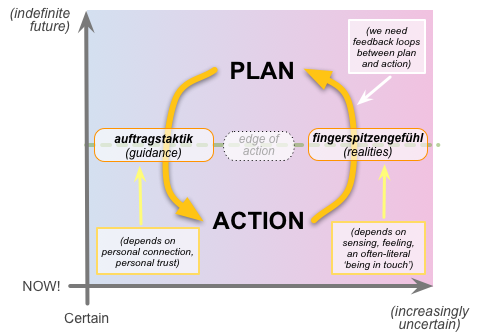

For architects, the catch is that that loop is crucially dependent on a swathe of themes and factors that would be completely invisible to a mainstream IT-centric ‘enterprise’-architecture – themes such as person-to-person connection, sensing, ‘feel’ and, above all, trust:

To ensure that the ‘shadow’-elements work well for the enterprise, and are appropriate covered in the organisation’s structured ‘governance of governance’, enterprise-architects must explicitly include and incorporate those ‘hidden’ themes into the architecture.

(For more on the themes themselves, see my Integrated-EA slidedeck ‘Invisible Armies: information, purpose and the real enterprise‘; for more on metagovernance or ‘governance-of-governance’, see the post ‘Towards a whole-enterprise architecture standard – Worked example‘.)

As the literal ‘the architecture of the enterprise’, a real enterprise-architecture must, by definition, cover every aspect of the enterprise – including all of the ‘shadow’-elements. And yet, also by definition, those ‘shadow’-elements cannot be brought ‘under control’ – not least because they deal with the themes and factors that are beyond the reach of conventional concepts of ‘control’. We need to acknowledge their existence, learn to work with them – and yet also allow them to remain somewhat ‘in the shadows’. As enterprise-architects, we ignore these facts at our peril… – and no, it’s not an easy balance, though one we somehow must achieve.

Comments or suggestions, anyone? If so, over to you…

Hello Tom,

Thought provoking article. Often the notion of shadow (IT and the likes) have had a negative connotation – disruptive,hard to manage, leads to duplicity , etc.The flip side is that these constructs (Shadow enterprise) might act as a catalyst for the slow moving enterprise (Does this conforms to bimodal theory ?)

I am seeing more and more organisation employing an Innovation function, which reports to the CIO/CFO.The function helps ideate, incubate and socialise the products before they are added as enterprise’s value propositions.

The governance should ensure that both – the real enterprise and the Innovation should have hand-offs defined (around when the POCs becomes an enterprise value proposition) and methods and processes to guide strategic alignment.

Thanks, Prashant.

On “I am seeing more and more organisation employing an Innovation function, which reports to the CIO/CFO.The function helps ideate, incubate and socialise the products before they are added as enterprise’s value propositions” – yes, agreed, important. And the crucial part – that’s completely absent from Gartner’s description of ‘Bimodal’ – is that one about socialisation of innovations, making sure they work in the real-world. There’s more on this in the next post, coming up later today.

“And yet, also by definition, those ‘shadow’-elements cannot be brought ‘under control’ – not least because they deal with the themes and factors that are beyond the reach of conventional concepts of ‘control’.”

Indeed. These are largely cultural things that cannot be created, but can either by encouraged or discouraged. The more open it is that these unofficial channels exist to handle the unexpected edge cases, the healthier I’d consider the organization. Conversely, if the “French Resistance” works in the shadows, flouting the rules in order to actually get work done – that’s a red flag.

“The more open it is that these unofficial channels exist to handle the unexpected edge cases, the healthier I’d consider the organization. Conversely, if the “French Resistance” works in the shadows, flouting the rules in order to actually get work done – that’s a red flag.”

Strong agree on both those points, Gene – which is where and why a delicate yet firm and fully-nuanced (meta)governance is so important for all of this.