Hope, optimism and delusion

Yes, I work in and around the fringes of enterprise-architecture and the like – but my long-term background is more in medicine. So for me, one of the quiet pleasures of the new-year ‘holiday season’ is reading through the Christmas edition of the BMJ (British Medical Journal). It’s the one time in the year where the BMJ goes all ‘Ig Nobel‘ on us, with a whole double-edition chock-full of articles “that first make people laugh, and then make them think”.

This year was no exception, with serious, well-researched yet often wonderfully-funny articles exploring whether full-moon is a hazard to motorcyclists (which, apparently, it turns out to be), the impact of 1960s ‘brutalist’ architecture on hospital patients (somewhat surprising), whether ‘man flu’ is a real phenomenon (short answer: yes) and whether Peppa Pig has incited watchers to overuse healthcare.

But from a whole-enterprise-architecture perspective, the article that most caught my interest was not one of those delightful side-excursions, but a mainstream editorial, ‘Hope is a therapeutic tool‘ (cite: BMJ 2017;359:j5469). Central to this was a pair of definitions:

[It] is important to differentiate hope from optimism. Optimism is an individual’s confidence in a good outcome, whereas hope is a goal oriented way of thinking that makes an individual invest time and energy in planning how to achieve their aims.

We might argue about the specific words ‘hope’ or ‘optimism’ are appropriate for the respective concepts, but the distinction between those two concepts themselves should be clear enough. The article then continues:

[Hope] consists of two interactive components: first, routes to achieve the desired goals and, second, agency, or the individual’s directed intention and persistence. For example, an optimistic person with asthma would expect few attacks and not carry an inhaler, while a hopeful person would aim for good outcomes but still ensure an inhaler was available.

In this sense, the optimist assumes that nothing will go wrong (and the pessimist assume that everything will go wrong), whereas the hopeful person would ‘hope for the best but prepare for the worst’. In other words, hope aligns with the old Arab aphorism that we should “trust to Allah, but tie the camel first” – whereas this kind of optimism can too easily collapse into self-delusion.

The key point of the article was that the attitude and practice of hope tended to give significantly better therapeutic outcomes than did an over-reliance on optimism.

It strikes me, though, that the exact same principles apply in enterprise-architecture and the like. In particular, they would seem to relate all too well to the influence… – well, baleful influence, to be blunt about it – of the classic ‘big-consultancy’ approach to innovation and the like.

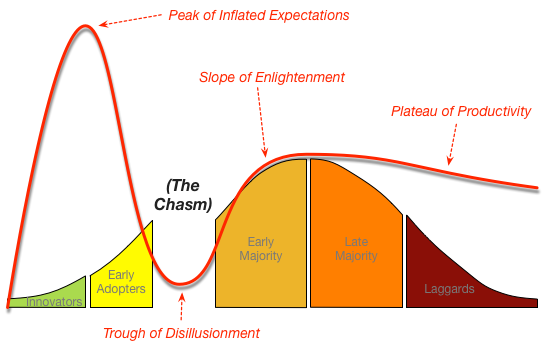

As I’ve written about in several previous posts (such as ‘Big-consultancies and bridging the chasm‘ and ‘Big-consultancies and getting it right‘), we have a huge problem for innovation in business and elsewhere, arising from inflated expectations and the like – otherwise known as hype. We can illustrate this by mapping Gartner’s ‘hype-cycle‘ against Rogers’ et al.’s classic technology-adoption lifecycle:

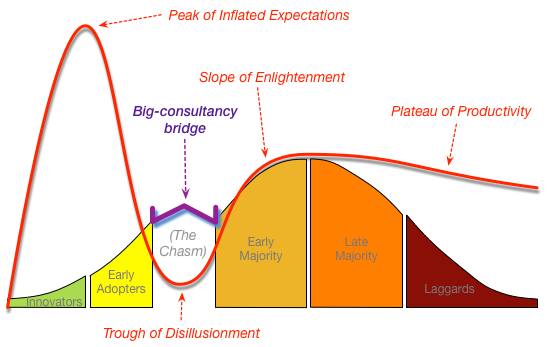

And also noted in those posts how the big-consultancies purport to provide a bridge across Rogers’ ‘the Chasm’, between Early-Adopters and Early-Majority, as a means to avoid (or at least seem to avoid) the worst of the ‘Trough of Disillusionment’ in the hype-cycle:

That distinction between optimism and hope provides another way to make sense of what’s going on there, and the risks around what happens if we aren’t careful about how and when we make use of those distinctions.

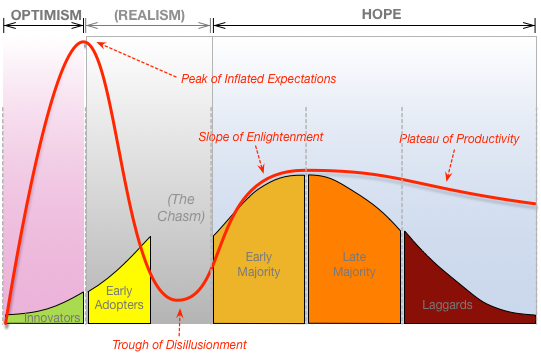

Optimism is what drives the hype-cycle – that wishful-thinking that somehow this time it will be different, that this time it will actually work, will actually fulfil its initial promise. But eventually Reality Department will present its demands for presence in the story – and that’s when realism must necessarily kick in. Whilst riding the realism all the way down to the hype-cycle’s ‘Trough of Disillusionment’, we need to avoid collapsing into pessimism, throwing the whole thing away and losing any possibility of value gained, of benefits-realised or lessons-learned. But if we can avoid that form of failure, then we can use a tempered form of hope – in other words, optimism balanced by realism – to gain the use and exploitation of whatever that innovation might offer.

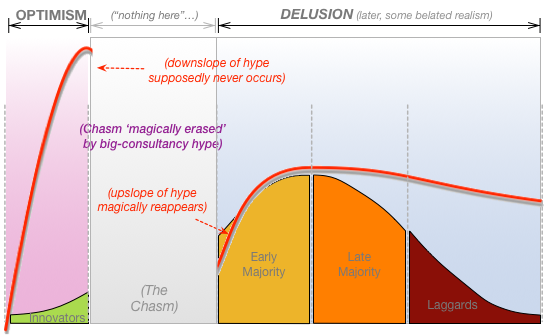

In human terms, the catch is that facing up to reality is real hard work – dispiriting, debilitating, even dangerous at times. Hence humans being humans, there’s always someone who’ll pretend that all the advantages can be gained without any of the hard work – everything’s ‘upside’, with never a sign of ‘downside’. When the big-consultancies swarm around a story, that depressing descent to the ‘Trough of Disillusionment’ seems somehow magically erased, swept behind the curtain: everything is rosy, wonderful, Better, Shiny, New, The Best Thing Since Sliced Bread, Believe Us!!! Yeah, we’ve all seen that. Been burned by that. All too often. Which is why the wiser ones amongst us have learnt to be more than a bit wary about all the big-consultancy hype…

However bleak it might seem, that realism-phase cannot and must not be avoided. Not if we want the innovation to work in the real-world. If we do try to avoid it, what we end up with is a mess in which misplaced optimism underpins dangerous levels of delusion – otherwise known as Not A Good Idea:

Probably the most dangerous form of delusion is a kurtosis-risk, a risk in which the potential losses greatly outweigh all of the gains made by ignoring that risk – see my post ‘What happens when kurtosis-risk eventuates?‘ for more on that. This is not just at the individual level: sometimes entire industries are still so cavalier about very-real kurtosis-risks that many would best be described as playing a game of ‘Pass The Grenade‘ – a industry-wide variant of ‘pass the parcel’ or ‘hot-potato’ but with far more lethal results. Again, it’s Not A Good Idea…

Optimism is important, yes, but it must be tempered by realism, and expressed in the real-world through what that BMJ editorial describes as ‘hope’. Without that balance, the overblown optimism will drive us towards the kind of delusions, from which, in some cases, we may never be able to recover.

So how does this play out in your organisation, your enterprise? How do your architectures support the right kind of hope, and keep the excess optimism at bay? What are the challenges that you face in bringing the right amount of realism to bear upon every opportunity and risk? Over to you for your comments on this, if you wish.

Hope as “optimism balanced by realism”. A beautiful and thoughtful post to kick off this year. Thank you Tom!