Big-consultancies and getting it right

As with all small independents in just about any industry, my /our relationship with ‘the big boys’ in enterprise-architecture is, yeah, kinda ambivalent at best.

It’s not just that they make the most noise, grabbing most of the attention and most of the money too – which they definitely do. That’s galling enough as it is. But perhaps even more it’s that, increasingly, much of what they do is not only not as new or ‘innovative’ as they claim, but that much of the big-consultancies’ advice is mis-framed, misleading or just plain wrong – perhaps not so much for the business of the past, but certainly so for where business is headed. And given the scale of their operations and their impact, that’s a serious worry for all of us – or should be, at any rate…

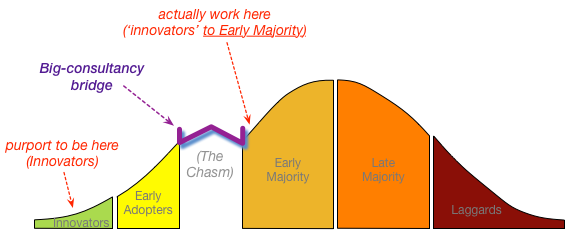

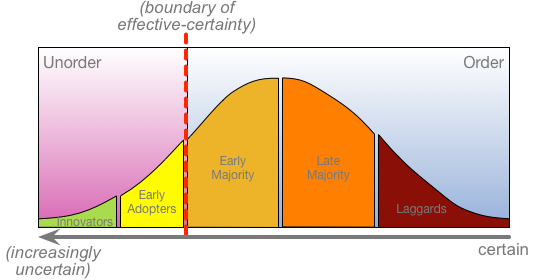

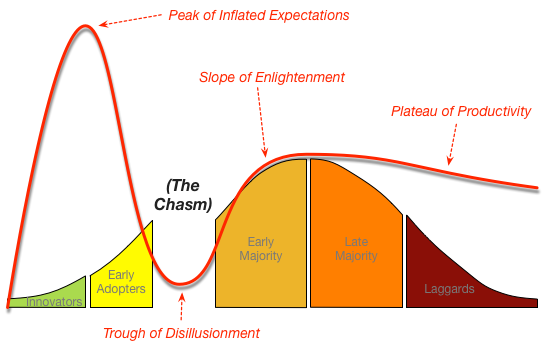

In the previous post, we looked at how big-consultancies position themselves in the market, as analysts and supposed ‘innovators’. In reality, their positioning is more like ‘sort-of innovators for the Early Majority’, providing a bridge across Geoffrey Moore’s ‘the Chasm‘:

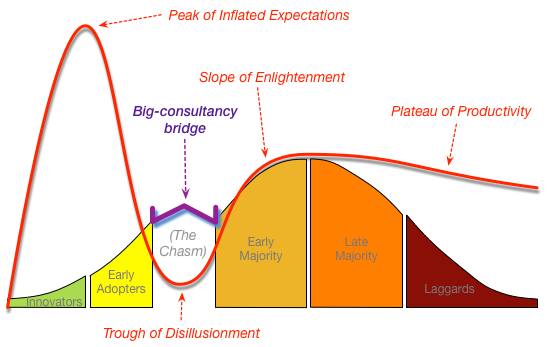

In practice, though, the Chasm exists only because of mismanagement of sensemaking-discipline in the earlier stages of innovation-adoption, giving rise to what Gartner describe as the Hype-Cycle. The Chasm occurs where the previous over-hype collapses to what Gartner call the Trough of Disillusion, which spooks the over-eager yet also highly risk-averse Early Majority:

Since the big-consultancies themselves are often some of the key promoters of that dysfunctional hype and its subsequent collapse, then to some extent their positioning as ‘innovators to the Early Majority’ provides a purported ‘solution’ to a problem that they themselves have caused. Oops…

Yet there are two other themes about the big-consultancies’ business-models that were mentioned in the previous post that we haven’t yet explored:

- they offer to simplify complex ideas – but often do so in dangerously-simplistic ways

- they offer supposed certainty – but with ideas, models and metaphors that may be just plain wrong

The need for simplicity and supposed-certainty both arise in part from the demands of the Early Majority – but the reality is that they can be hugely problematic, and often downright destructive. Let’s look at each of these themes in turn.

The impact of over-simplicity

The big-corporates are key participants in the Early Majority, for many types of innovations. But as Early Majority, big-corporates have an urgent ‘need’ for simplicity and certainty. Given that the big-corporates are the key clients for most big-consultancies, the latter are only too happy to oblige them in those purported ‘needs’.

But the danger with simplifying something is that it can be all too easy to over-simplify, to the point where crucial nuances are lost. And if the person doing the simplifying doesn’t fully understand what those nuances are, or why they’re so important, then the result risks not only being overly-simplistic but perhaps even dangerously wrong. Let’s pick up on two recent concepts from Gartner to illustrate this: Outside-out, and Bimodal-IT.

(A reminder that this isn’t about Gartner alone: all of the big-consultancies seem to fall for errors of this type. And many of those other errors are considerably worse than than the two examples explored here – one of the more egregious examples in enterprise-architecture right now being the misframing and mismarketing of the TOGAF/Archimate pairing.)

From what I’ve seen to date, the term ‘Outside-out‘ first seems to surface from Gartner in their report Future of EA 2025 – Evolving From Enterprise To Ecosystem, by Marcus Blosch and Betsy Burton (Gartner ID:G00269850 [summary only]), back in October 2014.

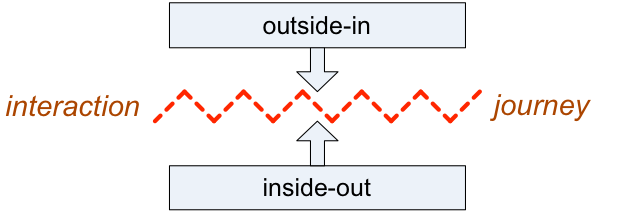

The contrast between ‘inside-out’ versus ‘outside-in’ has been around a long time, of course, as perspectives for an organisation and its business, and as a way to understand ‘customer-journey’ and the like:

But when Gartner first presented their notion of ‘outside-out’, it was taken by many to be something completely original, completely new:

In the Gartner ‘EA 2025’ article, ‘outside-out’ is described as follows:

Outside-Out: … Taking an outside-out perspective starts with an even broader focus beyond the enterprise and its known customers, partners and competitors, into the world of possible (unknown) customers, constituencies, partners and stakeholders. With this broad perspective, EA is focused on understanding the trends that could affect the business and its ecosystem, then working inward to determine and guide changes to people, processes, information and technology to drive these outcomes. The focus is on disruptions well beyond the immediate scope of the organization (be it new technologies or competitors, for example) that could drive change and innovation.

In reality, ‘outside-out’ is not a new idea at all – not in enterprise-architecture, anyway. To my knowledge, I was the first to describe the concept, in my post ‘Inside-in, inside-out, outside-in, outside-out‘, back in June 2012 – but there may well have been others before me. And this is a public website, after all, and a key part of my work is about making new ideas as openly available as possible – so I’m not saying that Gartner plagiarised the concept from me, or from anyone else either. For example, they could well have arrived at their concept independently, as a logical progression from ‘outside-in’. Yet whether the idea ultimately came from me or not, the key point is that when Gartner crew simplified the idea down to a form more easily accessible for their Early Majority clients, their version of the ‘outside-out’ concept has left out some crucial nuances – which can make it dangerously-misleading in real-world practice.

The easier nuance-problem is that, on its own, ‘outside-out’ – the world beyond customers and other direct-transactors – can risk becoming dangerously unbalanced:

It must be balanced by ‘inside-in’, to ensure that the internal systems and processes all connect correctly to support the outside-in customer-needs:

Okay, the organisation’s senior management might think they don’t need inside-in: much of it is at a level of detail that they don’t want to engage in, after all. But without that balance, it becomes all too easy, for example, to create an enterprise-architecture in which the organisation’s marketers will find themselves selling things that can’t actually be delivered – otherwise known as Not A Good Idea…

The real problem with Gartner’s ‘outside-out’, though, is that they’ve started from the wrong place, the wrong metaphor – and their over-simplified version of the ‘outside-out’ concept succeeds only in making those mistakes that much worse. It does extend the view onto a usefully broader range of enterprise-stakeholders – but not enough to address a whole swathe of utterly-crucial concerns for the organisation and its enterprise-architecture.

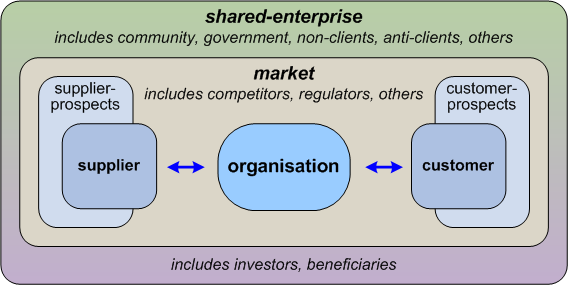

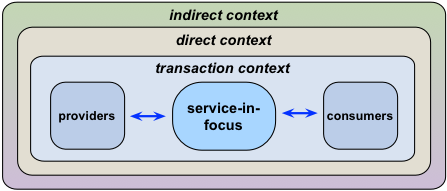

To illustrate what’s gone wrong, and why, and what to do about it, we first need to step back a bit. The start-point I’d suggest for this is my ‘Organisation and enterprise‘, which begins with two assertions: ‘the enterprise’ is not the same as ‘the organisation’, and ‘the enterprise’ is always larger in scope than just ‘the organisation’. The post ‘Organisation and enterprise as ‘how and ‘why’‘ expands on this somewhat with another set of related assertions, that the organisation is ‘how’, the enterprise is ‘why’; and since the ‘why’ for a context must always be larger than the ‘how’, the scope of ‘the enterprise’ must always be larger than the scope of ‘the organisation’.

My position is that if we fail to understand and work with these key points, we would literally be unable to do enterprise-architecture. But in almost all cases – including this one we’re exploring here – the big-consultancies fail to grasp the criticality of these assertions: and, as a result, when they talk about about ‘enterprise-architecture’, it’s not enterprise-architecture that they’re talking about at all. At best, it’s something much more limited and constrained – usually organisation-wide IT-architecture. At worst? – well, you get the picture…

Yeah, that serious.

And yes, I’m serious about it being that serious.

The key here is that there are two main dictionary-definitions for the term ‘enterprise’:

- Definition E1: “an endeavour, a bold undertaking” – hence the linkage to the concept of ‘entrepreneur’

- Definition E2: “a large organisation or consortium” – most often a for-profit corporation

If we choose Definition E1, then our description of ‘enterprise’ is bounded by whatever the endeavour is. It encompasses anyone who’s engaged in that ‘bold undertaking’, at any scope and scale. It’s fully fractal: it can be much larger in scope than the organisation, as a ‘shared-enterprise’; or it can be a subset of the organisation, exploring a single department or business-unit within the organisation. It also links cleanly with concepts of motivation, of the why behind relationships between stakeholders in a shared-enterprise.

But if we choose Definition E2, then in effect ‘organisation’ and ‘enterprise’ become exact synonyms. There’s no fractality, no subset or superset: the only possible scope is ‘enterprise = organisation’. And if we do that, then ‘enterprise’ literally ends at the boundary of the organisation – which means that we would have no means to describe anything at all beyond the organisation. No means to describe customers, suppliers, prospects, regulators, analysts, activists, recruiters, investors, journalists, markets, competitors, government, or anything else beyond the boundaries of the organisation. And also no means to describe motivation, the reasons why people would or would not choose to connect with the organisation and its own ‘bold endeavour’.

(One of the key purposes for ‘outside-out’, done properly, is that it enables architects to explore drivers within the shared-enterprise context as if the organisation itself does not exist. This is essential if we’re to identify service-gaps in the overall shared-enterprise space, and the organisation’s options for positioning itself within that that space. Note, though, that this exploration is only possible with Definition E1. It’s not possible with Definition E2, because according to its assertions, if the organisation does not exist, then neither does the enterprise, and hence no possible ‘outside-out’ relationship between them. Or ‘outside-in’, for that matter.)

In enterprise-architecture, the concept of ‘enterprise’ that we need is Definition E1. It’s the core definition that underpins those assertions earlier above, and that enables us to reach out to the full scope and scale of ‘shared-enterprise as shared-endeavour:

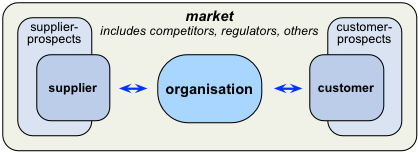

For enterprise-architecture, Definition E2 is definitely ‘Not A Good Idea…’ – it’s hopelessly constraining, hopelessly misleading. In effect, if we’re lucky, all that it gives us is this:

Which isn’t much use. Especially if we need to connect with anything beyond the organisation.

The catch is that Definition E1 requires an ability to think fractally, to think in terms of abstracts, to use systems-thinking, to view a shared-context from any point within that context, any perspective, all as equals. Unfortunately, these are not common traits amongst most businessfolk, and nor are they often found – or even acknowledged – in most mainstream business-education.

By contrast, Definition E2 fits comfortably and well with most businessfolk’s view of the business world, and of themselves as the centre of everyone else’s business world. Unfortunately, it’s also a classic example of HL Mencken’s wry epithet that “for every complex question, there is at least one answer that is clear, simple, easy to understand – and wrong”.

But big-consultancies market their wares to mainstream businessfolk. No surprises, then, that pretty much all of the big consultancies would settle for Definition E2, ‘the enterprise is the organisation is the enterprise’. And the fact that this definition doesn’t work for enterprise-architecture – in fact is just plain wrong for the purpose – doesn’t seem to matter to them at all…

Yet because Definition E2 doesn’t work for enterprise-architecture, what we often see from the big-consultancies is a muddled mash-up of both definitions – in effect trying to use both definitions of ‘enterprise’ at once, even though they’re fundamentally different from each other. And then kinda wondering why it doesn’t quite make sense, but carrying on regardless anyway. Gartner’s definition of ‘outside-out’ above is a perfect case in point: it’s implicitly using Definition E2 throughout – ‘enterprise’ and ‘organisation’ as synonyms – whilst at the same time trying to describe ‘the enterprise beyond the enterprise’.

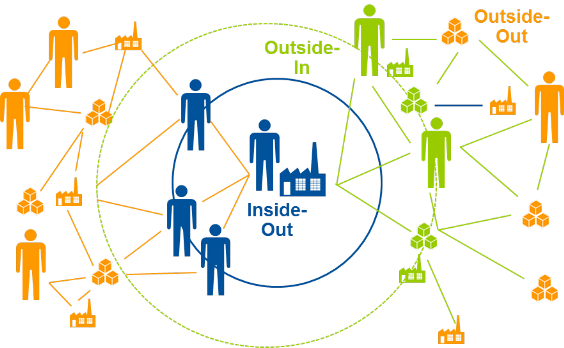

In effect, having used the wrong, narrowly-constraining term for ‘enterprise’, they’re now forced to think wider, with conceptual tools that just won’t stretch that far. We can see that they’ve sort-of grabbed onto the idea of ‘enterprise as ecosystem‘ – but they haven’t got that right either, because they’re still trying to cling on to that ‘the organisation is the enterprise’ definition at the same time. With some seriously messy kludges, they can sort-of claw their way to a messy sort-of description of ‘the enterprise that is beyond the enterprise’ that can just about sort-of stretch out to the scope of the broader market:

But because they haven’t started from Definition E1 – ‘enterprise’ as ‘a bold endeavour’ – there’s no way to resolve the fractality that goes all the way from outside-out to inside-in, no real way to describe non-clients or anticlients or communities or non-transacting stakeholders or even the organisation’s investors, and so on, and so on. Which means there’d be no way, for example, to describe hidden risks in business-model design, from outsourcing and the like, or hidden perils of co-branding, or kurtosis-risks and suchlike that, to that organisation, would seem to hit without any warning at all, but can wipe out the organisation’s business entirely. Oops…

Yeah, it’s a mess – a real classic ‘Not A Good Idea…’. Enough said, really.

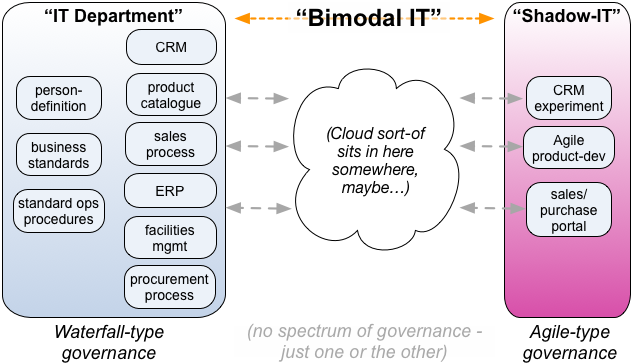

Another example of a big-consultancy over-simplification is what Gartner describe as Bimodal-IT. A typical Gartner article on ‘bi-modal IT’ describes the core idea as follows:

CIOs need to respond to the cataclysmic technology shift within their own organizations. The IT organization can’t turn into a digital startup overnight and, besides, there’s a raft of business-critical responsibilities that it simply can’t (and absolutely should not) divest.

The answer is bimodal IT. In Mode 1, IT operates traditional IT services, emphasizing safety and accuracy — what a traditional IT organization does best. Mode 2 emphasizes agility and speed, like a digital startup. Thus, one organization can operate at two speeds. The business coordinates, communicates, and leverages shared knowledge. More so, it focuses on one shared, not competing, goal: to improve performance.

Gartner presents this as something new, something that they alone have developed from scratch only in the past year. But in reality it’s not new at all, as one critic explains:

Whether you call it legacy versus emergent systems, Brownfield versus Greenfield deployments or sustaining versus disruptive technologies, the dichotomy between old and new or maintenance and development has been around since the dawn of IT. Each category has always required a different set of investment, management and governance techniques.

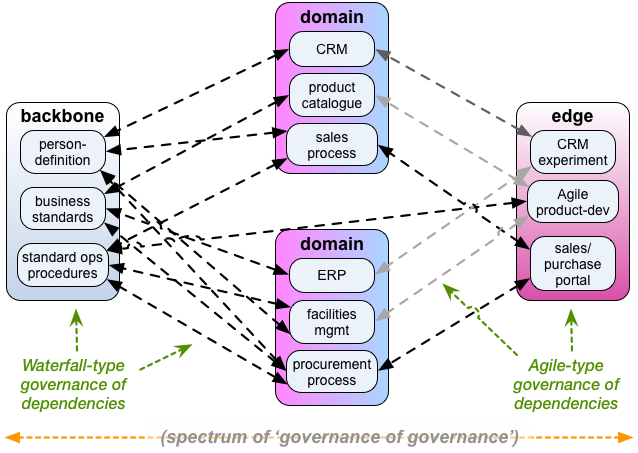

Anyone who looks at an organisation’s IT with a reasonably aware eye on how things actually work will soon come up with their own version of this split. It was certainly evident in our earlier EA work at Australia Post back in 2005, though it probably wasn’t until around five years later that I started putting a more formal structure around it, as ‘backbone and edge’. I described that model in a whole stream of posts here from April 2011 onwards, including ‘Agility needs a backbone‘, ‘Architecting the enterprise backbone‘, ‘Backbone and business-rules‘, ‘Migrating from edge to backbone‘ and ‘More on backbone and edge‘, and perhaps more publicly in my slidedeck ‘Backbone and edge‘ for the IASA conference in April 2013. In other words, all of it quite a while before Gartner’s supposedly-‘new’ ‘Bimodal IT’.

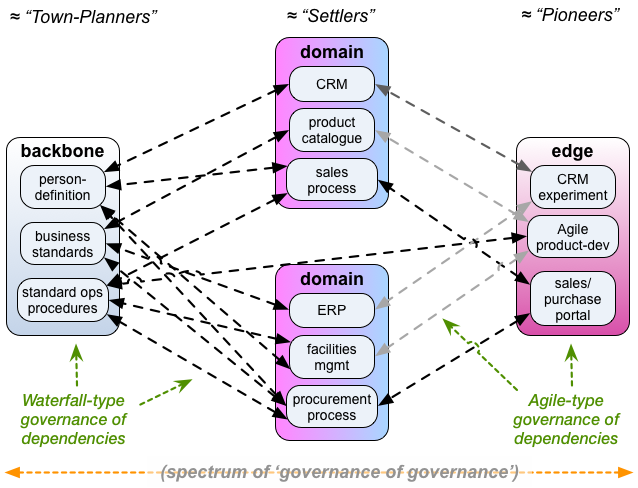

‘Backbone and edge’ is just a shorthand, though. It’s more accurate to say that the ‘backbone’ and the ‘edge’ are just the two extreme-ends of a spectrum of ‘governance of governance’, with all manner of domains and sub-domains and subsections somewhere in the middle. In its simplest form, we could summarise this spectrum in a visual layout like this:

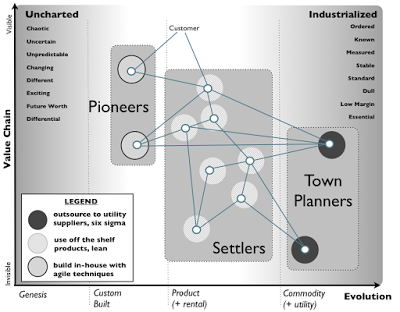

That trimodal or polymodal structure is important: bimodal is not enough for this purpose. And that’s borne out even more by the work of another independent who’s done a lot of development on this – Simon Wardley, and his concept of ‘Pioneers, Settlers and Town Planners’:

I probably came across his work somewhen around mid-2012, with his post ‘Pioneers, Town Planners and those missing Settlers‘, but he has earlier work on this back to at least 2005, and in turn points back to a closely equivalent concept (‘Commandos, Infantry, Police’) by Robert X Cringely, from way back in 1993. In short, ‘bimodal-IT’ isn’t new – and it isn’t right, either.

In effect, Simon Wardley’s model is laid out with ordered and certain on the right, and unordered and uncertain on the left – the other way round from backbone-and-edge, with the latter’s roots in the SCAN framework. So if we were to swap Simon’s model around left-to-right, it all lines up with backbone-and-edge much like this:

There’s a lot of extra detail in Simon’s model that isn’t in backbone-and-edge, but the core principles behind them are essentially the same: the two extremes, and various things happening in the middle.

By contrast, Gartner’s ‘Bimodal IT’ seems to consist only of the two extremes, with pretty much nothing in between them:

In his post ‘Bimodal IT – the new old hotness‘, Simon Wardley is scathingly blunt in his critique of ‘Bimodal IT’:

The whole purpose of the settlers is to productise i.e. to take the early stage work of the pioneers, and iteratively mature it until the town planners can finally industrialise it. They are absolutely essential to the functioning of such structures. Remove it at your peril.

So, yes, ‘Bimodal IT’ is a nice simplification of the real idea – but actually too much of a simplification. In effect, so-called ‘Bimodal IT’ is so simplified as to be dangerously simplistic. In other words, looks great on the surface, easy to understand and all that – but for real-world practice it’s definitely yet another big-consultancy blunder. Not A Good Idea…

The perils of prediction

Anyway, let’s come back to the other aspect of the big-corporates’ urgent ‘need’ for simplicity and certainty – the apparent obsession with certainty and control, which, as it happens, are inherently unattainable in the real-world. (There’s plenty of hard–science behind that assertion, by the way.) Again, given that the big-corporates are the key clients for most big-consultancies, the latter are only too happy to indulge them in this – whether or not those beliefs are actually valid.

So here’s a not-untypical sales-pitch from one of the larger IT-consultancies (I won’t say which), talking about enterprise-architecture:

Do you want your strategies to succeed? You’ll need the gentleman on the left. He designs your business. … He’s an obscure executive called an Enterprise Architect (EA) and he works for your CIO. … [Y]ou don’t want your strategies following spaghetti roads – you want them moving through your company on logical, straight highways…

Why does he work for the CIO? Because the roads in your company are paved with technology – so the best way to ensure that they are straight is to build and control the tech. Techies invariably screw up the business; business guys screw up the tech. For decades we’ve looked for someone to span both – and that’s what Enterprise Architects do.

It looks good, doesn’t it? Looks like exactly what the typical Early Majority corporate client would want to hear? Sure. But there’s a slight catch: almost every statement in that quote above is wrong. And not just somewhat-wrong, but much of it fundamentally wrong – absolute howlers, in fact – in almost every possible way. Oops…

The detail of how and why it’s so wrong is in the posts ‘Broken‘ and ‘Why broken?‘, but we can summarise the key points as follows:

- enterprise-architects do not design the business

- strategies do follow ‘spaghetti roads – whether we like it or not

- few organisations these days would “build and control” all of the technology they use

- there is a lot more to a business than just its technologies

- most businesses use many technologies that would not come under the CIO’s remit

- ‘enterprise-architecture’ literally means ‘the architecture of the enterprise’ – not merely ‘the architecture of the enterprise-IT’

And techies don’t screw up the business, nor do business guys screw up the tech: that assertion is completely wrong, too. It’s just that both are coming at it from the assumption that their own view is the only correct one, and therefore the other view is necessarily false. That’s one reason why strategies will, at best, move through the company on ‘highways’ that are anything but logical, straight and smooth – and why the enterprise-architect must act as translator, or facilitator, to help sort out the resultant mess…

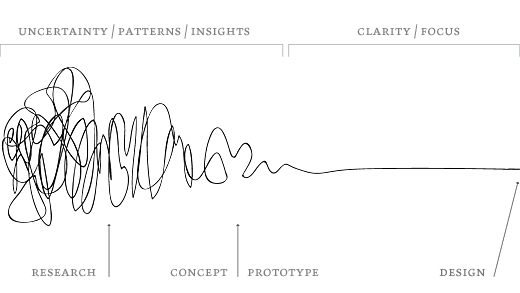

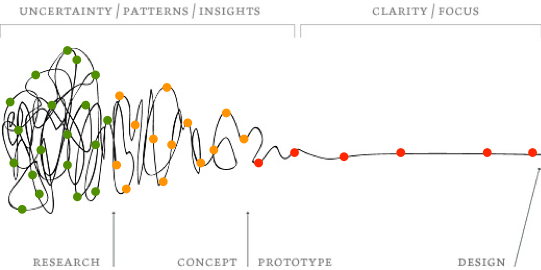

One of the classic descriptions of what really happens in innovation and change, and just how much not straight the change-pathways really are, is Damien Newman’s ‘the Squiggle‘:

Given that pretty much everyone in any kind of change would know this, then why on earth would the big-consultancies pretend that it doesn’t work that way? The answer, again, is about where their big-corporate clients tend to sit within the innovation-adoption lifecycle, as Early Majority:

The answer, as we saw in the previous post, is that Early Majority – and, in particular big-corporate Early Majority – are caught on a double-bind, largely of their own making. They’re desperate for anything new that would give them a competitive edge, so they need change, big-time; but at the same time they’re expected to deliver absolute and complete predictability, from budgets to performance-targets to shareholder-dividends and everything else, at every level of the organisation, every step of the way. And they’re very change-averse anyway, because of hierarchies and internal turf-wars and suchlike. Continual large-scale change, and very change-averse, and absolute predictability, stability and certainty, all at the same time? – this is not a recipe for a happy outcome…

Cue the big-consultancies, riding in to the rescue! The real role of the big-consultancy bridge is to provide the delusion that there’s nothing on the far side of it – that there is no scrubbly side to the Squiggle before the seemingly-certain ‘Clarity / Focus’, that there is no such thing as that so-scary ‘Unorder’. Everything’s nice, safe, predictable and certain; every change has a known outcome, “a notional future that is fully proven” and all that. That’s why the big-consultancies position themselves where they do, as providers of ‘innovations to the Early Majority’, in a form with which the big-corporate Early Majority can feel comfortable and safe:

Sure, it’s probably useful, and valid in its own way, possibly. At the least, it’s true that without bridge, many innovations in big-corporates would never happen at all under the current conditions and mindsets. The catch is that that sense of certainty is a delusion. Not entirely a delusion, of course: there are some certainties there. Just enough to prop up the delusion, anyway. But the inescapable reality is that Reality Department always includes both order and unorder – whether we’re ready for it or not. And the danger with the delusion is that it can leave people completely unable to cope with unorder when it hits. Ouch: Not A Good Idea…

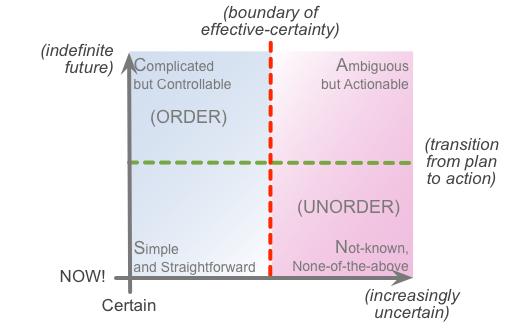

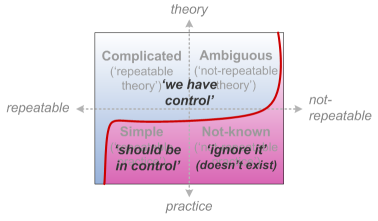

We can illustrate this somewhat with the SCAN framework – a simple frame within which to map out the relationship between certainty and complexity in a given context-space. The basic background for the frame looks like this:

Its horizontal axis goes from absolute-certainty on the left, to increasing-uncertainty over on the right – potentially all the way to infinite-uncertainty. (Note that this is the opposite way round to that shown for the Squiggle and the innovation-adoption lifecycle, so you may need to visualise a horizontal-flip on one or other frame to get them to line up.) At some point along that horizontal-axis, there’s a point at which, when we do the same thing, outcomes change from always giving the same results – on the ‘certain’ side – to either possibly, probably or always giving different results – on the ‘uncertain’ side. The positioning of this ‘boundary of effective-certainty’ is itself a bit uncertain – it can move around, under different conditions, for different people, or whatever. Kinda tricky in itself.

The vertical-axis for SCAN is the amount of time available before we must commit to action. This ranges from an immediate ‘NOW!’ at the base, where’s there’s no time left at all, and then analysis- and assessment-time extending upwards as an indefinite scale of time-before-action, where before-‘NOW!’ becomes a potentially-infinite time into the future. Again there’s a kind of transition at some point on that axis, where in effect we shift from ‘plan’ to ‘action’ – for which there are very different decision-making modes on either side of that boundary. And again, the position of that boundary too is fluid – it moves ‘up’ and ‘down’ according to context, pressure, urgency and suchlike.

We always have all of this in every context. If we were to do sensemaking and decision-making properly, we would select techniques for the respective aspect of the context-space that applies at each moment. We can describe those options in various ways, such as a set of techniques:

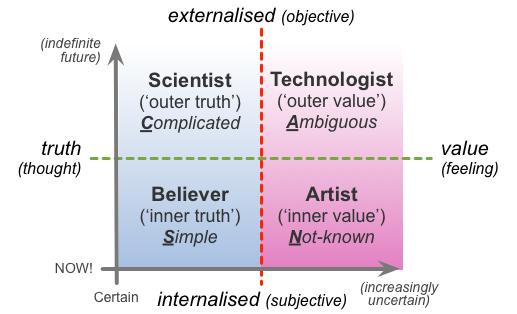

Or as modes:

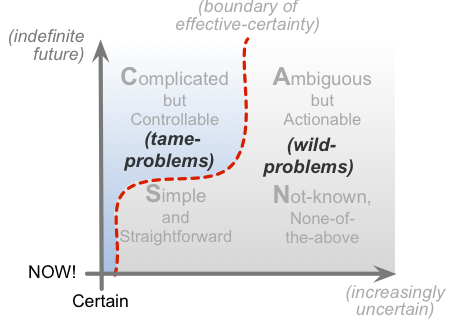

But remember again that both of those boundaries can be fluid, which means that the effective partitioning of the context-space can take other forms than than a simple two-axis grid. One such example is when we map out the distinction between ‘tame-problems’ and ‘wild-problems’ – tame-problems that are amenable to consistent, predictable ‘solutions’, versus wild-problems (or ‘wicked-problems‘) that aren’t, and have to be ‘re-solved’ anew every time.

The key here is that a lot of problems can seem a lot more predictable when seen from a distance than they actually are when we get down to the ‘NOW!’ of action – a mapping that looks somewhat like this:

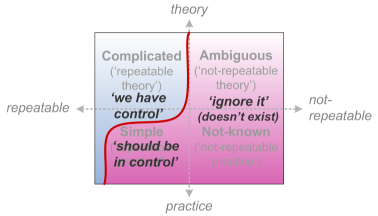

For IT-folks, this skew often doesn’t matter all that much, because anything that can’t be dealt with by IT ‘solutions’ is simply skipped over or ignored as ‘Somebody Else’s Problem’:

But over the entire organisation, the entire business-context, eventually everything is in scope, everything matters, and there is no Somebody Else: there will always be someone, somewhere in the business, for whom it’s going to be Our Problem – even if they don’t know it right now. Which means that that ‘someone’ has to be able to cope with uncertainty when it hits. But if uncertainty is anathema, even taboo – as it so often is in big-corporates at present – then yeah, we’s got a problem…

What really drives this kind of mess is what’s sometimes called the ‘linear-paradigm‘ – an assertion that everything ‘should’ eventually be reducible to predictable, controllable cause-and-effect. In reality, ‘control’ is only possible at all with tame-problems: by definition, it’s unavailable in any wild-problem context. (See Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety for the formal proof on that.) But if – for whatever reason – people choose to cling on to a concept of ‘control’, there’s a common tendency to assert that if there’s any conflict between theory and practice, then it’s the real-world that’s ‘wrong’ – not the theory. This creates some definitely-skewed perceptions about what’s real and what is not:

And that delusion, or disconnect from reality, gets even worse whenever the managers or whoever can hide away in a comforting world of ‘information with the crusts cut off‘. By that I mean the kind of ‘executive-dashboards’ that we see so often in business, where crucial nuances are stripped off at each pass of collating and simplifying as information moves ‘upwards’ through the hierarchy-tree. (The kind of executive-dashboards that big-consultancies and big IT-vendors are so keen to sell their clients, in fact…) The result is the skew gets even more extreme – a self-reinforcing echo-chamber – which, at executive-level, safely distant from any point-of-action, eventually loses any contact with reality at all:

In short, the linear-paradigm is really bad-news in any business-context. Unfortunately, it’s also really popular… – and some of its keenest promoters are, again, the big-consultancies.

Another example of this, in which the big-consultancies are again deeply involved, is the whole misleading notion of using ‘trends’ or past ‘track-records’ to ‘predict’ the future. The crucial point that we need to hammer home is that ‘prediction’ only makes sense with tame-problems – but ‘the future’ is always a wild-problem, always with inherent-uncertainties. To quote business and investing agility expert David Siegel:

The track-record bias: thinking that the performance of the past predicts performance in the future. This works well with mechanical systems and much less well with people and markets.

The exact same applies to trends – which, in essence, are just forward projections of supposed track-records. Which means that the whole ‘Trends’ concept is broken, before it even starts. It is, yet again, yet another means to use a spurious pseudo-certainty to provide a comforting delusion of certainty. Yet who exactly is deluding whom in the tangled multi-way ‘Trends’ game, and in what ways, for what outcomes, for whom, is definitely an open-question…

We’re in turbulent times, hence no surprise that a lot of people, in business and elsewhere, are seemingly looking around, anywhere they can, and with ever more urgency, searching for any signs of a return to the old certainties, or at least some kind of comfortingly-stable ‘New Normal’. That’s one of the main markets that the big-consultancies would seek to serve right now, with their ‘trend-analysis’ and their so-certain ‘Advice Notes’ and ‘Magic Quadrants’ and ‘Waves’ and ‘Playbooks’ and all that stuff.

But to me, all of that ‘search for certainty’ is a fool’s-errand. Or at best, a quest for fairy-gold – the kind that evaporates by morning, and leaves someone with a big hangover, a crowd of angry creditors and a great big unpaid bill. All of the signs (okay, yeah, there’s that implicit ‘trends’ term again, but at least with proper allowance for uncertainty) are that the business-world – the world in general – is likely to get a lot more turbulent yet. A lot more turbulent, with a lot of mythquakes and some seriously ‘stormy weather‘, both metaphoric and literal. For example, if some of the climate-change projections are even halfway correct – and so far they’ve more often proved overly conservative about the real rates of change – then we’re looking at a real risk of losing large swathes of coastlines and even entire cities worldwide, along with most existing maritime ports, all well within the current century. Very few enterprise-architects I know, and probably none at all of the big-consultancies, are as yet seriously exploring the implications of change on that scale – for which, as I put it in an article here some three years back:

The ‘New Normal’ is that there is no ‘New Normal’ – and there may well never be one, ever again.

Seems that the only certainty is that there is no certainty – and we forget that fact at our peril.

But let’s wrap up this section with a model that’s not from any big-consultancy, but is actually one of mine. I’m including it here because it’s probably one the most direct visual summaries of how and why the usual big-consultancy models are so flawed, and fail so often – and why big-organisations keep following those big-consultancy mistakes, time after time after time.

The core reason behind the mess is that both the big-consultancies and their Early Majority clients still cling on to the same flawed mindset about the structure and operation of an organisation – the linear-paradigm’s notion of ‘scientific management‘, a mechanistic, ‘top-down’, ‘control’-based concept of the enterprise often also described as Taylorism. It’s a mindset that did sort-of work for the industrial-era past of a century or more ago – but it’s completely unsuited for almost all of today’s far more complex social-era business-contexts.

(Most of the supposed ‘science’ in so-called ‘scientific-management’ is likewise a left-over relic from the industrial era of a century or so ago: it’s a very long way out of line with present-day science or scientific practice. Oh well.)

For today’s contexts, the key to all of this is what we’ve seen above: we must use Definition E1, ‘enterprise’ as ‘bold endeavour’, not ‘large [for-profit] organisation’; and we must drop the delusion of ‘certainty’ and ‘control’ in favour of a more fluid concept of direction, coordination and values-based connection. This allows us to describe the enterprise in a dynamic, fully-fractal way, which, from the organisation’s viewpoint, we could summarise like this, as we saw earlier above:

Or, in more abstract form, more amenable to a fully-fractal view:

This means that values and the meaning of ‘value’, for example, arise from the broader shared-enterprise – not the organisation on its own. Every enterprise is ‘for-profit’, in some sense – but the respective meaning of ‘profit’ is determined by the values of the shared-enterprise, and is never about monetary-profit alone. Which in turns means that ‘value-proposition‘, for example, is literally about how the organisation proposes to deliver value to the shared-enterprise as a whole – and not merely “a fancy term for your product or service”.

If we use a service-oriented view of the enterprise that aligns with that enterprise-summary above, with a strong futures-based concept of service-delivery, we would end up with a checklist-template for a generic but fully-fractal (‘any-scope / any-scale’) service-element that would look somewhat like this:

In other words, values-driven and values-governed, in alignment with the values of the broader shared-enterprise; a continual value-flow for its transactors, driven by a spiralling flow of change from future to present to past; and returning various context-appropriate forms of ‘profit’ to all of its stakeholders.

By contrast, most big-corporates and big-consultancies alike still hold on to a Taylorist, hierarchical, neo-feudal concept of ‘enterprise’, in which both ‘value’ and ‘profit’ are described almost exclusively in monetary terms, and in which the whole enterprise is deemed to be “a machine for making money” for the small subset of stakeholders who are deemed to be ‘the owners’. All of the values-driven structures needed for futures-oriented interaction and interrelationship with the shared-enterprise are collapsed and conflated into a past-oriented reframing of value-governance as ‘management’, and also riddled with linear-paradigm delusions of ‘control’, leading to fundamental concept-errors such as “a notional future that is fully proven”.

The result is that its concept of a service is metaphorically flipped into a form that is literally upside-down and back-to-front, profit-obsessed for its ‘owners’ only, driving sort-of forwards but only on the basis of what can be seen in the rear-view mirror, and with no guiding values at all:

And they then wonder why those organisations seem so dysfunctional and won’t work well? Well, duh…

But very profitable, of course, for big-consultancies who offer each time to fix the mess with the same models that caused that mess in the first place, in the classic Shirky Principle way, on and on for ever?

Hmph.

Surely we can do better than this?

Practical implications for enterprise-architecture

The answer is, yes, we can do better than this – but only if we wean ourselves and our stakeholders off from addiction to the big-consultancies’ business-models…

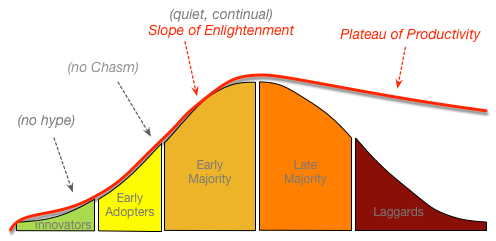

The first step is to get rid of the hype – to shift innovation-adoption from this:

…to this – which also gets rid of the Chasm, and thence the need for the big-consultancy bridge:

To do that, we need to pay careful attention to mitigating the seven sins of dubious discipline – and develop the meta-disciplines needed to counter those ‘sins’, too.

The next step is to develop a more realistic view of the big-consultancies’ offerings. Yes, sure, there’s a lot of glamour about everything they do, a lot of hoopla and razzamatazz about it, and that nicely comforting sense of certainty around all of it, too. But it’s kinda important to remember that, as a client, we’re paying for all of that glitz and glamour – and it doesn’t come cheap, in any sense of the term. And as we’ll have seen from the above and the previous post, by the time we get something supposedly-‘new’ from the big-consultancies, it’ll likely be years behind the real leading-edge, and over-simplified and quite possibly wrong – all of which might well matter a lot when we try to get the wretched thing to work in our own context.

Just to make it worse, it’s probable that anything we get from them will be purportedly proprietary to that consultancy alone – which in itself makes identification and mitigation of any errors and misframings that much harder, and makes adaptation to our own context that much harder too. And most likely whatever we get from them will have been reframed into a cookie-cutter ‘solution’ that will need to be adapted to our own context anyway – which we’ll need to do, since vendor-cost customisation usually cuts too far into their profit-margins to make it worthwhile. Which in turn makes us into the unwitting and possibly unwilling Innovator and/or Early Adopter for a case-study for that big-consultancy – from which, since everything they touch somehow magically becomes their own ‘proprietary intellectual-property’, they’ll probably then sell on our hard-won experience to others as ‘all their own idea’.

In short, the big-consultancies’ models often turn out to be a lot more expensive than they look – and expensive in a lot of different ways, too…

So since we have to be an Innovator anyway, just to get the big-consultancies’ stuff to work, why not choose to set out to do it that way ourselves, right from the start? That’s our next action – to learn how think and act like Innovators and Early-Adopters. We need to get comfortable with being uncomfortable; understand the dance between certainty and uncertainty; experiment with systems-thinking, design-thinking, hybrid-thinking; and learn how to make the Squiggle our friend rather than a much-feared foe.

And we need to stop thinking of the big-consultants’ bridge over the Chasm as a bastion against an uncertain world. Instead, we need to see it as a gateway – or a drawbridge, at least – outward to new possibility, new opportunity. (Better still, learn to recognise that the Chasm doesn’t even exist if we’ve kept the big-consultancies’ hype appropriately at bay…) Even if our organisation is deeply addicted to the big-consultancies’ advice, it’s important for us to build up our own competence and self-trust as Innovators and Early Adopters – and to be able to cross over to the far side of that bridge, and engage with other Early Adopters and Innovators too, whenever we need to do so.

Related to that, another action would be to break free from the linear-paradigm of predictability, certainty and ‘control’, and instead engage in developing new theory and practice for enterprise-architecture. The key point here is to acknowledge that the linear-paradigm does not work for most contexts that we need to deal with now in enterprise-architecture and the like. At best, it only works well within IT-only or tame-problem-only contexts – and those are becoming less and less common for the work we do. For the wild-problem elements of contexts such as outside-in for e-commerce or e-government, SoLoMo for marketing, smart-metering, citizen-science, internet-of-things, or the inherent mass-uniqueness in e-health concerns, we need a theory-base that’s fundamentally different – or at least fundamentally-extended – from the classic linear-paradigm and its too-limiting assumptions of linear-causality and the like.

With a few honourable exceptions, you won’t get those kinds of new approaches from the big-consultancies. But for quite a small amount of search-effort, you will be able to find them from within the enterprise-architecture community itself. For example, there’s plenty of innovative material just on this website, such as in the posts ‘Theory and metatheory in enterprise-architecture‘, ‘More on theory and metatheory in EA‘, ‘Models and reasoning-processes in enterprise-architecture‘ and ‘Hypotheses, method and recursion‘. But that’s merely one source, one person’s work, and there are plenty of others – such as all of those sources listed near the end of the previous post. It’s not hard to find, once we start looking for it. Or develop it ourselves, of course – and that way we’d know that it matches up to our own organisation’s needs!

Finally, one further action would be to engage in developing new ‘tools for the trade’. Most of the supposed ‘EA toolsets’ out there at the moment are useful only for the big-consultancies’ world, and – to be blunt – are often worse than useless for the work that we really do in enterprise-architecture. For a start, most of them are useful only for the far-right-hand ‘certainty’-oriented end of the Squiggle, and offer us nothing – nothing at all – to help with the chaotic, confusing scrubbly left-hand side of the Squiggle. Which is exactly where we most need toolset help. Bah.

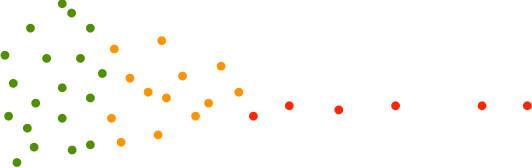

What we have right now is a dissociated mess of disconnected tools and toolsets scattered across the Squiggle:

…and if we take the Squiggle itself away from the picture, we can see just how disconnected they all are, relative to each other, with almost all of the so-called ‘EA tools’ unhelpfully positioning themselves way over on the right-hand side:

So although it’s still early days yet, there’s definitely an urgent need for some kind of tooling that actually supports the ways that we need to work. There’s some exploration of the requirements and practicable possibilities in a fair few posts here, such as ‘Pinball wizard‘, ‘Toolsets, pinball and un-dotting the joins‘ and ‘Toolsets for associative modelling‘ – but we need much, much more, from many different people. Join us in this, perhaps, if you would?

Anyway, wrapping-up:

- the big-consultancies do still have their value, for some purposes – and probably no-one should doubt that

- however, their tendencies toward over-hyped fads and cookie-cutter ‘solutions’ make them less and less relevant for our purposes in enterprise-architecture and the like

- in part because of their emphasis towards Early Majority big-corporate clients, their ‘solutions’ tend to be over-simplistic and over-certain, harder to adapt for the more complex nuances of each organisation’s EA needs, and often a long way behind the leading-edge of EA practice

- their mechanistic ‘cookie-cutter solutions’ business-model is ripe for disintermediation by niche-consultants on one side, and specific forms of self-adapting automation on the other

- probably the best sources now for much-needed innovation in enterprise-architecture are in the niche-consultancies across many different disciplines and industries, but maybe even more from the broader practitioner-community for EA, within all types of organisations, large and small

- perhaps the wisest move for all of us is to wean ourselves and our organisations away from addiction to the big-consultancies’ so-proprietary offerings, and learn to stand more on our own strengths and skills, sharing freely with each other as we go

Best leave it at that, I guess.

And yeah, I know that this has been an even longer post than usual – but I hope it’s been useful nonetheless. Let me know, perhaps? – and feel free to comment as you wish.

Can you please simplify your articles? 😉

Very interesting article. Specially Gartner Bi-modal. I’ve always regarded it more as marketing than actionable advice. If you want to simplify then maybe the effort should be on “simplifying” the underlying principles and logic but not necessarily the resulting conclusions. Then maybe bi, tri or x-modal is the end result for a particular enterprise.

On a positive note big consultancies make the discussion easier by giving concepts catchy names (even if we disagree about the concept itself).

@Osama: “Can you please simplify your articles?”

Okay, okay, critique fully accepted… 🙁 🙂 In my defence, two comments:

a) It would take much, much longer to write it shorter…

b) It actually needs that depth of analysis/assessment to explain what’s going wrong, and why, and what to do about it. There’s an old quote somewhere about “It takes an order of magnitude more effort to rebut bullshit as it does to create it” – which is exactly why bullshit is so darned common, and why it’s so hard to stop it.

(And that latter point applies not just to enterprise-architecture but to every discipline, domain, whatever. To give a not-so-political example, I was reading this morning in the BMJ [British Medical Journal] about the damage done by one well-known study on the effects of the drug paroxetine – used as an antidepressant for adolescents – which is still much-promoted as ‘proof’ that the drug works well, despite the fact that the study was proven to be invalid well over a decade ago. To quote the title of the article: “No correction, no retraction, no apology, no comment: paroxetine trial reanalysis raises questions about institutional responsibility”. Too right it does… – but when there’s big-money and big-reputations on the line, thinks can get a bit, uh, complicated…)

@Osama: “I’ve always regarded it more as marketing than actionable advice.”

Yep. Kinda reminds of what used to be said about the original IBM-PC: “a triumph of marketing over technical expertise”. :wry-grin:

@Osama: “…Then maybe bi, tri or x-modal is the end result for a particular enterprise.”

Yes, exactly. That kind of simplification is what I’d describe as a metaframework – a framework used in a ‘meta-‘ way to so as derive context-specific frameworks. The kind of frameworks we see from big-consultancies try to go the other way: an overly-simplistic context-specific framework rebadged as if it’s a universal ‘solution’ – TOGAF being an almost archetypal example of that.

@Osama: “big consultancies make the discussion easier by giving concepts catchy names”

The problem there is that the ‘catchy name’ can itself be a major cause of problems – particularly if it creates a term-hijack. Again, enterprise-wide IT-infrastructure architecture as ‘enterprise’-architecture, is a classic case in point. Another that I’ve seen cause huge political and social problems is the reframing of ‘violence against adult women by adult males’ as ‘domestic violence’ [DV]: it’s entirely true that violence-against-women is one class of domestic-violence, but it’s by no means the only one, in fact in terms of hospital-data it’s not even the most common. When a ‘catchy name’ is applied to a gross over-simplification (“a triumph of marketing over technical expertise”), serious problems will occur for someone – though usually not, we might note, the people most actively promoting the ‘catchy name’… Oh well.

Tom writes:

“since the ‘why’ for a context must always be larger than the ‘how’”

We’ve been back and forth on this in the past, and I still don’t understand this assertion. Why must this be the case? And what is the metric for “largeness”? What does it mean for a “why” to be “larger” than a “how”?

What does it mean for the “scope” of an “enterprise” to be “larger” than the “scope” of an “organization”. Are these “scopes” even commensurable?

And since I’m with you on everything else, why is this assertion so important? Nothing that follows seems to me to hinge critically on it. The critical thing seems to me to be that the concepts we denote by “organization” and “enterprise” are different and must be clearly distinguished from one another, lest we mix things up that are qualitatively different. Making what seems to me to be a handwaved assertion about comparative “scopes” only obscures this fundamental point, one that the greater EA community is either actively resisting or simply doesn’t get.

I write about this distinction (from a different perspective) in my “Len’s Lens” piece “Is vs. Does” in the December 2015 issue of the Journal of Enterprise Architecture.

And where is “what” in all this?

len.

@Len: “We’ve been back and forth on this in the past…”

Yes, we have. Far, far too often. Hence please accept my apologies for considerable irritation and near-extreme frustration…

@Len: “…and I still don’t understand this assertion.”

To me this is so elementary and so fundamental to all architecture, of every possible kind, that I literally cannot understand your failure to understand the assertion. As you say, we’ve been back and forth on this too many times, and I just don’t know how to get it to make sense to you, any more. But I’ll do one more try…

The core to this – as I think we’re agreed? – is that ‘enterprise’ and ‘organisation’ are not the same. (The crucial distinction is in the choice of Definition E1 versus E2 above: ‘enterprise’ as ‘a bold endeavour’ (E1), not as ‘large commercial organisation’ (E2).) Each of those types of entities has its own distinct scope, bounded by ‘rules, roles and responsibilities’ for ‘the organisation’, and ‘vision, values and commitments’ for ‘the enterprise’. In effect, an organisation is about the ‘how’ and the ‘with-what’, whereas an enterprise provides a ‘why’. To use your terms, the organisation is a ‘does’, whereas the enterprise is an ‘is’.

(A crucial aside: both of these types of scope are fractal – each scope can have supersets, subsets and/or intersecting-sets of the same type. The two types can coincide, or not – as in the classic business-centric view of the E2 definition where ‘the organisation’ has the same scope as ‘the enterprise’. But the fractality also means that these scopes can be at any scale: as per ISO42010, ‘the organisation’ can extend outward to broader consortia and the like, or ‘downward’ to a sub-department, a project, even potentially a single line of code. I admit ‘the organisation’ is not a good term for ‘any scope of action bounded by rules, roles and responsibilities’, but courtesy of the current limitations of the English language, it’s probably the only one we have that would make some degree of sense to most people. Ditto for the fractality of scope for ‘the enterprise’, of course.)

What I’ve been trying to explain you – so, so many times now… – is that, architecturally the organisation cannot be its own ‘why’. To do so would be to confuse means with ends: the whole thing becomes circularly self-referential. (That’s the core reason why Definition E2 is unusable for our purposes in architecture.) To be able to anything useful, we need to create a gap between ‘how’ and ‘why’ – not least to create a tension that provides motivation to do things, and to give a reason to ‘outsiders’ to interact with the organisation.

Which means that for a given ‘the organisation’ (fractal, remember?), it needs to connect with and identify itself with a ‘the enterprise’ that is ‘larger’ in scope (vision, values, commitments) than its own scope (rules, roles, responsibilities). By definition, the organisation will only have a purpose meaningful to others if it connects to a scope larger than itself.

You’ll need a concrete example. Right in front of me, right now, is the annual report of a national telecom organisation. It states that its ‘brand-promise’ is “to bring people instantly closer to what matters to them by putting them at the heart of everything that we do, offering them to best quality and service”. These are people ‘outside’ of the organisation, being viewed as the driver for the organisation. The respective enterprise (people wanting to be ‘instantly closer to what matters to them’) is a scope that is larger than that of the organisation making that respective brand-promise. The enterprise for customers (and also for suppliers) of the organisation is a scope of direct transaction with the organisation. We could describe that enterprise-scope as one step ‘outward’ from the organisation.

And it states that ‘Our sense of purpose’ is that “We constantly keep people in touch with the world so that they can live better and work smarter”. Note that that enterprise-scope (people who want to ‘keep in touch with the world so that they can live better and work smarter’) includes the organisation’s customers but also extends much further, to include customers of other telcos in that region, regulators, journalists, prospective customers, direct government agencies, and suchlike. These people are not in transactional relationship with the organisation at the present time, but they’ll often interact in some way. In other words, a shared-enterprise that has a scope of direction-interaction with the organisation. We could describe that enterprise-scope – more commonly known as the organisation’s ‘market’ – as two steps ‘outward’ from the organisation.

Beyond that, that ‘sense of purpose’ of ‘people who want to keep in touch with the world so that they can live better and work smarter’ extends much further, to people who share that same need or purpose, but who will probably never transact or even interact directly with the organisation – not in terms of its main value-flow, anyway. For example, these include telco-customers in other countries or continents; they include communities, families, government-agencies outside of the telco space; they include the organisation’s investors and beneficiaries. This is a much broader shared-enterprise that has a scope only of implied or indirect-interaction – indirect, but potentially still very relevant to the organisation’s viability, and even its survival, representing risks such as loss of ‘social license to operate’, or risks to continuance of the market itself via technological and/or social disruption. We could describe that enterprise-scope – which is the outer limit of the scope I usually consider as ‘the shared-enterprise’ for enterprise-architectures – as three steps ‘outward’ from the organisation.

(This also answers your question about “What is the metric for ‘largeness’?” – the short answer is that there isn’t any metric as such, in fact the whole concept of ‘metric’ or ‘commensurable’ is fundamentally misleading here. The ‘three steps’ are determined not by spurious metrics, by relationships relative to the organisation: transactors, direct-interactors, indirect-interactors.)

@Len: “Nothing that follows seems to me to hinge critically on it.”

No? Well, it’s fundamental to TOGAF. Before the big-consultancies started meddling in TOGAF, somewhen between TOGAF 7 and TOGAF 8, the actual focus-of-concern – ‘the organisation’ – was IT-infrastructure. That is the only operational scope for which TOGAF actually makes sense – everything else is just the ‘enterprise’ that provides ‘the relevant context’ for the scope of the organisation of IT-infrastructure (i.e., classically, the scope, remit and responsibility of ‘the IT-Department’).

Model it out, using the BDAT-stack, or, preferably, the BIDAT-stack:

— Who are the ‘transactors’ for IT-infrastructure? Answer: data-flows and IT-applications – otherwise known as ‘Information-Systems Architecture’.

— Who are the ‘direct-interactors’ for IT-infrastructure? Answer: human-interpreted business-information – otherwise known as ‘Information-Architecture’ – and the process-oriented human interactions that are the transactors of ‘data and applications’ – otherwise known as part of what TOGAF calls ‘Business-Architecture’.

— Who are the ‘indirect-interactors’ for IT-infrastructure? Answer: broader business-processes that do not directly interact with IT-supported applications and data, and business strategic and tactical choices about same – otherwise known as the remainder of what TOGAF calls ‘Business Architecture’ (and quite a lot more, actually).

In other words, TOGAF uses exactly the same scoping-structure as I’ve described above. (The fact that, for the most part, it does it very badly, with demonstrably very poor understanding of what it’s doing, and often tries to run the whole frame back-to-front and upside-down, is another problem entirely…) Hence ‘the greater EA community’ is not ‘resisting’ this point, about ‘layering’ of scopes – all that’s wrong is that it describes it in a completely screwed-up way.

@Len: “The critical thing seems to me to be that the concepts we denote by “organization” and “enterprise” are different and must be clearly distinguished from one another, lest we mix things up that are qualitatively different.”

That’s a “critical thing”, but not “the critical thing” – and that a really, really crucial distinction . What I’ve been trying to explain, all of this time, is that there are a discrete set of key points that we have to clarify here, together, as a unified whole – and it doesn’t work if we try to do them separately, as you seem to be insisting:

1. ‘The organisation’ and ‘the enterprise’ represent different scopes.

2. Those scopes effectively denote ‘how’ and ‘why’ respectively (rules and roles for actions, versus ‘a bold endeavour’).

3. An organisation (‘how’) chooses a broader enterprise to act as its ‘why’, its existential context. (This connection to a scope ‘larger than oneself’ is key to motivation and to interaction and transaction: in that sense the chosen ‘the enterprise’ must be ‘larger’ – have a broader scope – than ‘the organisation’.) For enterprise-architecture purposes, this context denoted by ‘the enterprise’ will typically need to extend outward to include transactors, direct-interactors and at least some types of indirect-interactors – i.e. ‘three steps larger’ than the scope of ‘the organisation’.

4. This structural-‘layering’ is fully fractal: it applies to whatever we choose as ‘the item-in-focus’.

5. This structural-‘layering’ is always relative to whatever we have chosen as ‘the-organisation-in-focus’, and goes ‘outward’ only. (There’s another ‘layering’ that goes ‘inward’, but it works in a somewhat different way, not from ‘how’ to ‘why’ but from ‘how’ to ‘what’ and ‘with-what’ – though that’s a topic for yet another separate-but-related series of posts…) It does not make sense to try to run this ‘layering’ ‘upside-down’, as TOGAF does with its Information-System Architecture, and even more with its so-called Business Architecture: doing so leads to arbitrary scope-exclusions (IT-centrism, in TOGAF’s case) that will cause architecture-ineffectiveness and architecture-failure.

Again, these points are all interdependent on each other – so don’t try to treat them separately. I know a lot of people will want to do that, because doing so enables people, for example, to keep deluding themselves that the BDAT-stack can work both ways, and that it defines the totality of all that we need in enterprise-architecture – which it can’t, and doesn’t. (This is one of the core reasons, by the way, why I’m so insistent that we need, very publicly, to scrap TOGAF, Zachman and Archimate completely in their current form, and start again properly with a fractal-type model: given their fundamentally wrong-headed paradigmatic-models, their continuing supposed ‘success’ in the marketplace is perhaps the key reason why enterprise-architecture as a discipline is still in so much difficulty to this day. Oh well.)

To me, all of this is really simple, fundamental, basic, core… – the kind of thing that to me every enterprise-architect should and would need to understand right from the get-go, or otherwise be unable to do any competent or viable work at all. Can you understand my frustration here, my exasperation at having to explain these ‘EA 101’-level concepts to you, yet again, and again, and again? And yet I know that you’re a real master of ‘the trade’: so this seeming inability to make sense of these really basic concepts itself just doesn’t make sense – what the heck is the problem here for you? Despite my huge respect for you, I will admit it really does feel now that your constant reiterations of a demand for explanation on this is not “simply doesn’t get”, but more like “actively resisting” – yet I have no idea why on earth you would do so, it just makes no sense at all… So I just hope upon hope that this time this has at last answered your concerns on this – because I just cannot keep on doing this for you, time after time after time. Sigh…

Tom replies to me, unhelpfully,

“What I’ve been trying to explain you – so, so many times now… – is that, architecturally the organisation cannot be its own ‘why’”

I get that. What I don’t get is why you insist “why” must be “larger” than “how”. I don’t understand what you mean by “larger”.

“To use your terms, the organisation is a ‘does’, whereas the enterprise is an ‘is’.”

No, that’s exactly backwards. An enterprise is what an organization does. An organization has physical existence. An enterprise “exists” (“is”) only when it is being done. When it is not being done, it is only a concept, and exists only as some representation of what it will be when it is being done.

“the short answer is that there isn’t any metric as such, in fact the whole concept of ‘metric’ or ‘commensurable’ is fundamentally misleading here.”

Wow. You’re the one who introduced the concept of “larger”. If you don’t actually mean “larger” in the way that most of us understand it (i.e., involving related concepts like metrics and commensurability), maybe you should look for a different word to denote the concept you really do mean.

“These are people ‘outside’ of the organisation, being viewed as the driver for the organisation. The respective enterprise (people wanting to be ‘instantly closer to what matters to them’) is a scope that is larger than that of the organisation making that respective brand-promise.”

OK, this helps me understand where our thinking diverges. If I correctly understand what this implies about your thinking (and at this point I can’t be sure that I do), this is going to take more than a frustrated reply here to get at.

“To me, all of this is really simple, fundamental, basic, core… – the kind of thing that to me every enterprise-architect should and would need to understand right from the get-go, or otherwise be unable to do any competent or viable work at all. Can you understand my frustration here, my exasperation at having to explain these ‘EA 101′-level concepts to you, yet again, and again, and again”

Really. This is so condescending I don’t know what to make of it. If this is all so obvious, why doesn’t the entire community of enterprise architects get it? Why do you have to keep explaining it, not just to me, but to everyone else as well?

I understand the difference between an organization and the enterprises it participates in. We differ about what exactly the nature of that difference is. You have this annoying argumentative style of assuming that if I differ with you about one aspect of your argument, I don’t understand any of it. Then you lecture me about things that I have explicitly agreed with for years.

“and it doesn’t work if we try to do them separately, as you seem to be insisting”

No, I’m not trying to separate them, I’m trying to understand one of them. I too have a set of arguments that only work when they are all considered together. What I don’t understand is what role this particular assertion (“whys are always bigger than hows”) plays in your total argument, the outcome of which I completely agree with.

“I will admit it really does feel now that your constant reiterations of a demand for explanation on this is not “simply doesn’t get”, but more like “actively resisting””

No, I am not actively resisting. The assertion that all whys are intrinsically “larger” than the hows that they motivate simply makes no sense to me. And I don’t understand why this assertion is necessary to understanding that the why is different from the how. I really DO want to understand what you mean, because this seems so important to your understanding of that difference. None of your explanations actually explain this to me. You just repeat things that I already understand and largely agree with.

No response necessary.

len.

Hi Len

Thanks for sending me your ‘Is vs Does’ piece, from the current Journal of Enterprise Architecture’.

Reading it, I think I can see the source of the problem we’re currently having.

#1. There are three core concepts in play, which we might summarise as:

— ‘What’ (structure)

— ‘How’ (behaviour)

— ‘Why’ (purpose)

#2. I’m using the term ‘Enterprise’ to denote Why, but conflating both What and How into the term ‘Organisation’ – which, as you correctly point out, is probably a mistake.

#3. You’re using the term ‘Enterprise’ to denote How, and ‘Organisation’ to denote What – but leaving no term at all for Why, which is probably also a mistake. (The same mistake also indicates why the concept of ‘larger’ makes no apparent sense to you – it’s the Why that’s ‘larger’, but there’s no Why in your denotation-model.)

#4. My allocation of Organisation and Enterprise leads to Organisation as ‘Does’ (How – What is implied) and Enterprise as ‘Is’ (because Why/purpose is the reason the organisation exists); your allocation of Organisation and Enterprise leads to Organisation as ‘Is’ (What/structure) and Enterprise as ‘Does’ (How), but no mention of Why/purpose. In that sense, neither/both of us have it ‘backwards’ (as you put in your comment), because both of us are wrong (we’ve both tried to use two terms to describe three different concepts).

#5. If we have to decide which is the ‘better’ of the two mistakes, I’d still argue that my version of ‘Enterprise’ is closer to that original definition of ‘enterprise’ as ‘a bold endeavour’, because the core of that definition is ‘bold’ (purposeful – Why) and ‘endeavour’ (striving towards something – also Why), rather than merely the activity of endeavouring (How). But it doesn’t mean that my definition is ‘the right one’, because it’s wrong anyway in the sense of #2 above.

#6. Also – and importantly – our usage of ‘organisation’ and ‘enterprise’ here tend to imply it’s all at a kind of somewhat-a-bit-variable-but-really-just-single-layer-‘whole-of-corporation’-like level, and hence mask the actual point we’re both really aiming for here, which is not just about resolving the What/How/Why turmoil but also clarifying the fractality and intersecting-set-ness of it all (as per the Eames ‘Powers of 10’ reference and the ‘Fig.9’ diagram in your article). Which is likewise a mistake on both our part.

All of which indicates that, yes, I need to write yet another blog-post (or two, or three…) on this. 🙁 In particular, it’s not just that I need to separate out the What and How, but I also need to show how the fractality also works the other way round, looking ‘downward’ from higher-level aggregation (not abstraction, as you rightly say in the article) toward the finer-grained detail.

Right now best leave it at that, I guess.

Ahh, this old chestnut. Ready for roasting on an open fire, I guess 🙂 ‘Tis the season …

I’m tempted to make my usual point about the futility of trying to make a technical term out of a highly-overloaded, standard natural language word. But then again, nah.

Agreed, sadly. Yet seems like we have to do something, however clunky, however overloaded, otherwise there’s no way to communicate at all. Oh well…

(But thanks, anyway.)