Services, customers and citizens

If we provide a service that is a monopoly or natural-monopoly, how should we relate with those who use our services? What’s the most appropriate metaphor to use, to guide our decision-making?

I’ve been thinking hard about this for quite a while now, in part from the work I’ve been doing around the ongoing disaster-area of politicised meddling with the NHS (UK National Health Service), and comparing that to other natural-monopolies such as rail-transport (in Britain, another politicised disaster-area…), electricity-supply, telecoms-infrastructure and water-supply (which, in Britain at least, has been tended to be one of the rare success-stories of privatisation – in environmental-impact terms, anyway).

Perhaps the most extreme example of a natural-monopoly is government. Almost by definition, we don’t get any choice about this: government literally comes with the territory. Okay, yes, there might be ‘competition’ of a kind as to who will ‘take control’ of government for the duration, and we might sort-of have some limited choices about that – but government itself continues on, regardless of who might believe themselves to be at the helm. (See any episode of ‘Yes, Minister‘ for a more honest picture of who’s really in charge… 🙂 ) We might note, though, that one of the more interesting developments in service-design in recent years has been the way in which governments – and the UK Cabinet Office in particular – have taken the lead in ‘customer-journey mapping‘ [PDF], viewing the citizen as a ‘customer’ of government-provided services. So would this work in the same way for other natural-monopoly contexts?

A couple of days back I was fortunate to have a catch-up meeting with Nigel Green – he was briefly back home from his current enterprise-architect role in Hong Kong – and this was one of the topics we explored. He suggested that for commercial natural-monopolies, we might actually be better to view the relationship the other way round: customer as citizen – a ‘citizen’ to whom the natural-monopoly has much the same social and other responsibilities as for government.

It’s the same kind of disruptive-thinking as for government and ‘citizen as customer’, but the other way round.

So let’s think about this a bit.

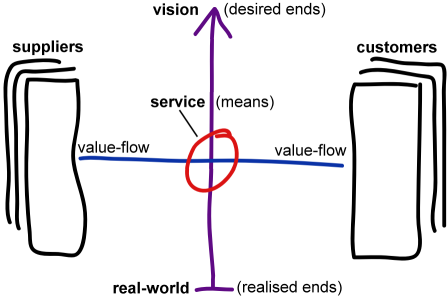

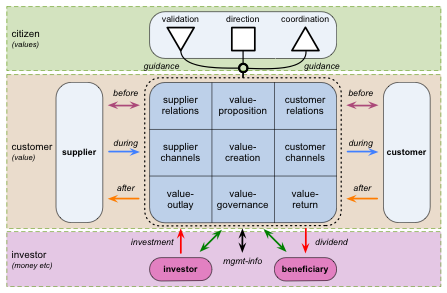

Start from the top, somewhat on the same lines as for Enterprise Canvas:

A monopoly or, even more, a natural-monopoly, provides a service.

In essence, everything is a service. Even if what it provides is products of some kind, it’s still a service.

And services serve. That’s why they’re called ‘services’.

Yet whom do they serve? How? In what way? And for what purpose, or whose purpose? – because that’s where things can get a bit messy…

The most basic idea of ‘a service’, or ‘service-delivery’, is in terms of value-flow – the creation and exchange of value, in terms of a specific category of product or service:

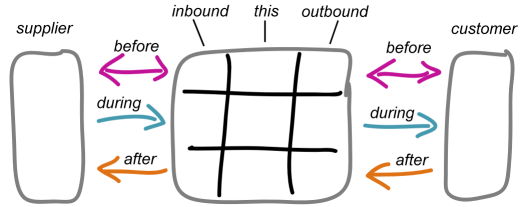

Or, to show the service itself in a more detailed form, showing the ‘before’, ‘during’ and ‘after’ flows relative to the main transactions:

The ‘before’, ‘during’ and ‘after’ flows relate to distinct phases in the Service-Cycle, the virtuous-circle of increasing trust that underpins all service-relationships. During the ‘before’-phase, the focus is on creating initial trust and relations; in the ‘during’ phase, the focus is more on setting up and enacting the transactions; and in the ‘after’ phase, the focus is mostly on completions, verifying closure, satisfaction and success:

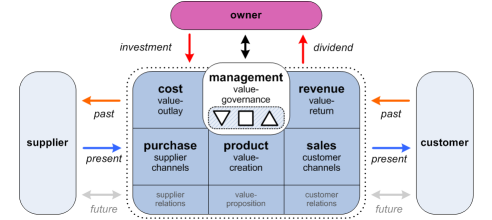

That part covers the value-flow through the service – the market-relationships. Yet it’s not a complete description of the service itself: we also need to understand the broader context – the values – as well as the value-flows of the market. From various sources, such as Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model, we can summarise a set of guidance-relationships as follows:

- direction: identity and purpose, strategy and context-awareness, tactics and run-time guidance for operations

- coordination: links with other services for coordination of strategy, change and run-time interaction

- validation: keeping on-track to enterprise values, quality and governance

(These types of guidance-relationships are often identified on diagrams by square, upward-triangle and downward-triangle icons respectively.)

There are also many support-relationships – HR, facilities, logistics, legal and so on – that underpin the day-to-day operations of the service. Most of these will be ‘inside’ the organisation-as-service – the entity seen as ‘the service’ within the market-context. For the ‘outside’ support-relationships, we can summarise these in terms of two key roles:

- investor: entity that provides support-value to the service, distinct from the market-flows

- beneficiary: entity the receives support-value from the service, distinct from the market-flows

(There’s more detail on these distinct types of values and flows in the posts ‘Modelling mixed-value in Enterprise Canvas‘ and ‘Assets and services‘.)

We can summarise that overall set of relationships in visual form as follows:

The conventional view of a commercial business usually suggests that its only relevant ‘external’ context is its relationship with its financial-investors, who, as ‘the owners’, are also its only beneficiaries. In that view, all of the guidance-services are subsumed into management, which acts exclusively as the agent of the owners. In effect, its primary function, as a service, is deemed to be to maximise the monetary profit for those owners, with everything else considered as ‘overhead’ that must be ruthlessly and relentlessly minimised – a set of structural relationships that we could visualise as follows:

In reality, if we compare that to the Enterprise Canvas relationship-structure, it’s clear that this is not only dangerously incomplete, but is also almost perfectly back-to-front and upside-down in terms of its relationship to time and in its relationship to its broader context. It also sets up inherently-combative ‘win/lose’ relationships between the financial-investors and almost everyone else – which is probably not a wise move…

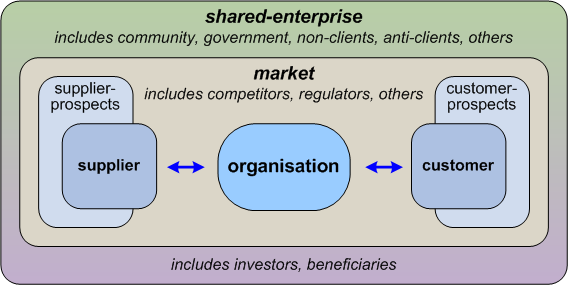

One way out of this is to apply a somewhat-extended of what I’ve usually called the Market Model, but is probably better termed the Service-Context Model:

This summarises the organisation’s or service’s relationships with its broader shared-enterprise – the vision or ‘story’ that guide all interactions in that context – in terms of three layered subsets: the direct supply-chain, the broader market that delimits the transaction-space, and the shared-enterprise that denotes the overall interaction-space for that context. To bring it back to the terms with which we started – customer and citizen – then:

- supply-chain: everyone is a direct customer of the ‘previous’ entity in the supply-chain

- market: everyone is a customer of someone else, and a stakeholder of everyone else, within the scope and terms of that market

- shared-enterprise: everyone is a citizen of that shared-enterprise

In a sense, ‘citizen’ is a synonym for ‘stakeholder’, in that everyone in the shared-enterprise has some kind of stake in every aspect of the shared-enterprise.

[There’s a very real sense in which ‘stakeholder’ can also be understood as ‘person holding a sharpened stake’ – with implied risks of an all-too-literal ‘point’ that perhaps need to be better understood by many business-folk… 😐 ]

By definition – because of that commitment to or stake in the outcomes of the shared-enterprise – every citizen-stakeholder is also an investor and potential-beneficiary. Hence it can be useful to extend the Market Model (Service-Context Model) to emphasise this dual-relationship – citizens as investor-beneficiaries, and investor-beneficiaries also as citizens:

The crucial point to understand here is that in many (most?) cases, the investment or dividend is not in monetary form. (Again, see the post ‘Modelling mixed-value in Enterprise Canvas‘ for more on this.) For example, people invest their trust in an organisation, and expect to see that trust repaid – such as in ‘good citizen’ behaviour by the organisation.

Also important is that these three roles of citizen, customer and investor/beneficiary – of which each person may enact any combination, each in many different ways – each connect and interact with the service in different ways:

- citizen: an emphasis on the values that guide the overall shared-enterprise, and the service’s relationship to and with that shared-enterprise

- customer: engagement in the value-flow as products and services are exchanged in the service’s transactions with the context of the market

- investor-beneficiary: engagement in the outlay/return flows of the forms of value that are needed to underpin the existence and operation of the service itself

Or, in visual form:

Note that the investor/beneficiary-flows go the opposite direction to those seen in the ‘customer’ relationship:

- investor is a kind of supplier to the organisation/service, but in forms of value that typically go outward to other suppliers

- beneficiary is a kind of customer from the organisation/service, but in forms of value that are typically received inward from other customers

Again, note that the types of value in the latter flows are often (usually?) different from those in the ‘customer’ flows: an investor may invest money, and a beneficiary may receive money, whereas the main forms of value flowing in the ‘customer’ transaction-space might well be toothbrushes or windows or flights or insurance-services or breakfast. Conversely, the ‘customer’-type value-flows in a banking-type enterprise may well be mostly in monetary form, but the investor-beneficiary flows there include themes such as social trust in the banking-system itself – and the system will fail if that investment is withdrawn.

Hence we need to take very real care to ensure that a valid balance is maintained between investors and beneficiaries – who may not be the same people – and also that all forms of value, and the transformations between forms of value, are fully acknowledged and maintained in mutual balance. For example, if a community invests its trust and commitment in an organisation, and that organisation transforms that commitment into monetary form that’s then provided only to the financial-‘owners’, the organisation is likely to find that its ‘social licence to operate’ – to use Charles Handy‘s term – will at some point be forcibly and angrily withdrawn, seemingly ‘without warning’.

So to summarise this in terms of where we started:

- everyone in the shared-enterprise space is a citizen of that shared-enterprise, and hence of every service that operates within that shared-enterprise

- by definition, every ‘citizen’ in the shared-enterprise is also an investor-beneficiary of every service in that shared-enterprise, in some form(s) of value – and their only choices relate to how they invest and receive dividend-return

- in a multi-player market within a broader shared-enterprise, a customer can choose their supplier of services – and will evaluate the value of those services in terms of the declared or implicit values of the overall shared-enterprise

- in a monopoly ‘market’, a customer cannot choose their supplier, but will still assess the value of those services in terms of the overall-enterprise values – and will be able to use the ‘citizen’ and/or ‘investor-beneficiary’ channels to take action if the perceived-value does not match up with the values-promise

Every customer is also a citizen; every citizen may (or, in a monopoly-context, must) also be a customer; every citizen is also an investor-beneficiary, who may well be able to withdraw their investment at any time. There are a lot of important implications that arise from the fact of these relationships…

Implications for enterprise-architecture

True whole-of-enterprise architectures will be essential here: organisation-centric ‘business-architectures’ or, worse, IT-centric ‘enterprise’-architectures are too narrow in scope, and could well be dangerously misleading and incomplete.

Service-modelling needs to take account of the full set of interactions and interdependencies of the service – not solely the transaction-oriented ‘customer’-type relationships. (See the post ‘Enterprise Canvas as service-viability checklist‘ for practical detail on how to do this.)

Value-flow modelling for investor-beneficiary relationships needs to take all applicable forms of value into account – not solely monetary investment and return. In general, it’s wise to model all investors as ‘equal citizens’, and not to assign arbitrary priority to so-called ‘owners’.

[Yes, we do need to be (very) aware of the politics of this: yet for this purpose we do need to take a stakeholder-neutral view – otherwise we will not be able to identify the full palette of opportunities and risks in that context. For safety’s sake, though, it’s usually wise to make it explicit that politics and priorities are considered ‘out of scope’ for this part of the work: at the strategic level, an architect’s role is primarily decision-support rather than decision-making – and whilst we must provide the full information that a decision-maker needs, we should not attempt to usurp those decisions ourselves!]

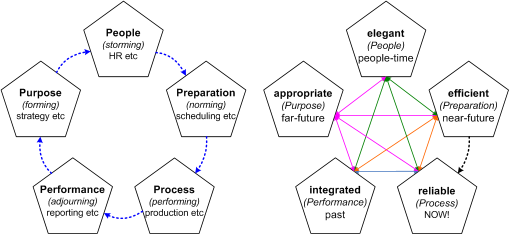

Include in the assessment all of the model-types summarised above – shared-enterprise values, Service-Cycle, Service-Context Model, and Enterprise Canvas with the ‘citizen’, ‘customer’ and ‘investor-beneficiary’ relationships. It will probably also be useful to include some of the ‘Five Element’ models, such as:

- focus-themes in different phases of the internal view of the overall Service-Cycle: purpose, people, preparation, process, performance

- related focus-themes and time-perspectives on effectiveness: appropriate (‘on purpose’), elegant (simplicity, clarity), efficient (best use of resources), reliable, integrated (‘everything supports everything else’)

Or, respectively, in visual form:

In a monopoly context, developing an architecture for continual-improvement of overall effectiveness becomes extremely important, because the usual feedback-mechanisms of ‘the market’ may not or will not be available.

We also need to beware of the common over-focus on ‘efficiency’ at the expense of almost everything else: doing so tends to drive a ‘race to the bottom’ in which the overall value of the service becomes so eroded that it eventually falls into catastrophic collapse – from which no-one ‘wins’. The focus must always be on overall effectiveness, as summarised in the Five Element diagram above – and not solely on ‘efficiency’.

Probably best if I leave it at that for now: any comments, anyone?

Great stuff Tom – especially for those who haven’t already seen your enterprise canvas – and a great example of what it’s all about too. So two birds with one stone.

On a humorous note I was reminded by the government as natural monopoly paragraph of the old anarchist slogan “whoever you vote for, the government wins”.

Tom,

Thank you for your excellent post. I have worked in an IT function of the Higher Education sector for over 20 years. For the most part, Higher Ed IT is a monopoly. We talk about our customers/clients as “Community Members” which matches well with my thinking about citizens. I am working with my new team here in the UAE to implement Service Management and specifically a Client Facing Service Catalogue. Your post (as always) gives me some great ideas to frame how I want to talk about service delivery to my team (suppliers) and our community (customers).

Thank you very much. Leo

Stuart, Leo – many thanks for kind comments on this – much appreciated! 🙂