On power

What is power? Where does it come from? Where does it go? Who has it? Who doesn’t have it? Who should have it? Who shouldn’t have it? And why? – or why not, for that matter – to any of those questions…?

Perennial questions indeed, in just about any social context. But let’s apply to those questions some of the tactics from RBPEA (Really-Big-Picture Enterprise-Architecture), and see what comes up.

(Note: This is an edited version of an earlier post on power – part of a larger series of posts about five years ago, on systems-thinking, social-theory, and disruptive societal-scale mythquakes. That post – in fact probably the whole series – was probably a bit too technical for most people’s needs, so I’ve simplified it here to focus instead on business-usable concepts of power.)

(See also the YouTube video ‘Introduction to SEMPER power-model – Tetradian on Tools For Change‘ for a more visual introduction to some of the concepts of power described here, and their business-implications.)

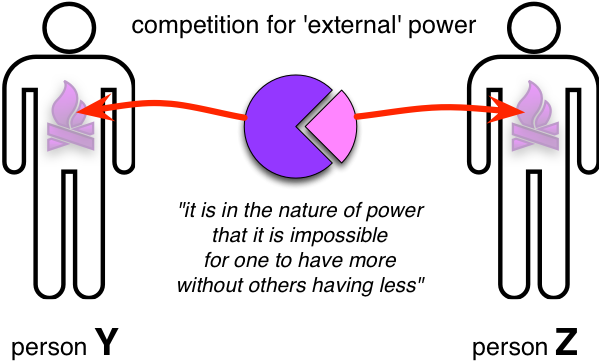

So let’s start off with a hoary old classic: the notion that power exists as a kind of magic pool or reservoir, somewhere ‘out there’ (though we never quite know where), of which there’s only ever a fixed amount. We don’t really know what power is, but we do know that we want our share of the pie – and if necessary we’ll fight others for it. Or more of a share, if we can. This ‘pie-slice’ concept of power is perhaps best typified in the assertion that “It is in the nature of power that it is impossible for one to have more without others having less”:

This kind of ‘zero-sum’ or ‘transactional’ thinking gave rise to a popular assumption in many ‘activist’ domains: that if one group felt they didn’t have much power in their lives, it was because some arbitrary ‘the Other’ had taken it all – had stolen their rightful slice of the pie. In which case, all that that ‘powerless’ group needed to do to become powerful was to set up structures to disempower ‘the Other’ as much as possible – to “force him to give up his position of power”, to quote one such activist-group. The assumption was that when ‘the Other’ has less power, that first group must, by definition, now automatically have more: the ‘stolen’ slice of the pie would somehow magically transfer itself back to that first group – without them actually having to do anything to make it happen. Disempowering someone inherently empowers others: that was the assumption.

In the activist circles I was personally engaged in, back in the 1970s or so, it was, as I say, a very popular belief – and unfortunately often still is. Back then, a fair few of us, struggling with politicised guilt and ‘shaming’ for being who we were, we spent a lot of painful effort in putting ourselves down, blaming ourselves for all others’ ills, as the various activist theories of the time commanded us to do. The catch was that it just didn’t work: we felt a lot worse, of course, but the others around us didn’t feel any better – in fact they often got even angrier and more demanding because it didn’t work. Everyone lost out: and it just kept on getting worse and worse.

In hindsight, and with even a modicum of actual thought, it should be obvious what went wrong: the power-model was based on a myth – an arbitrary, untested assumption – without any linkage to anything real. We had no idea of what power was, or where it was situated: all that we knew was that we all felt that we didn’t have it either, and hence assumed that someone else (unspecified) must have taken it. Not very bright of us, when we look at it like that…

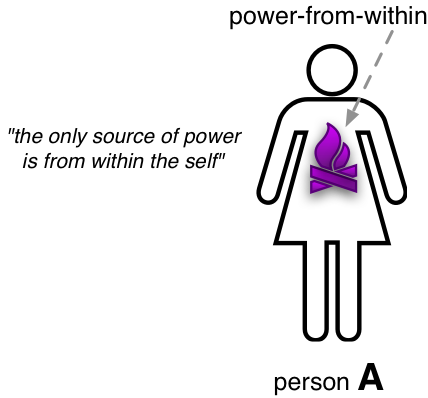

Eventually there at last began to be some real alternatives to the pointless ‘pie-slice’ model of power. One of these, in the 1980s, came from feminist theorist, Starhawk (Miriam Simos), who developed a power-model based on a concept of power-from-within. “The only true source of power”, says Starhawk, “is from within the self”:

In this model, we still don’t know what power is, but we do at least know where it is, where it comes from, and, from that, also have some idea of how to create it. That’s a huge improvement over the ‘pie-slice’ power-model.

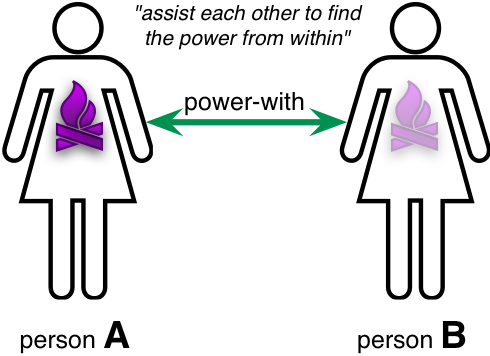

She then adds an important twist, about the social aspects of power. “We can assist each other”, she says, “to find the power from within” – an interaction that she describes as power-with:

This ‘power-with’ provides a positive-feedback loop through which more and more power can be created, seemingly from nowhere, but ultimately from within each individual.

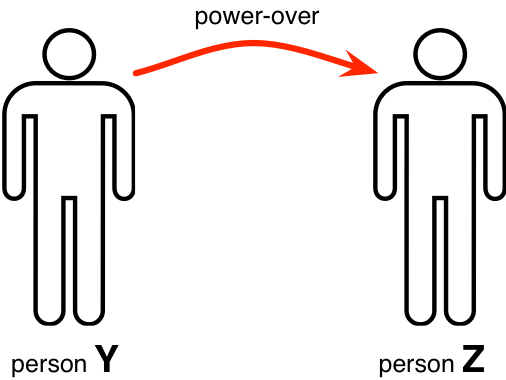

The catch, of course, is that the old ‘pie-slice’ power-model hasn’t gone away: there are all too many people who believe in the old slogan from The Godfather, that “true power cannot be given, it must be taken“. This creates an interaction that Starhawk describes as power-over:

Unfortunately, Starhawk’s power-model soon falls apart beyond those initial definitions above. (The earlier post provides the detail as to why it fails, but it isn’t particularIy relevant here.) The concepts of power-from-within, power-with and power-over do all work well enough as a starting-point – although, as we’ll see, we need a few amendments and extensions to that set. In practice, though, the crucial issue is actually the overall aim of each power-interaction: whether it is ‘with’ the Other, in one of many different senses, as a form of power-with; or ‘against’ the Other, likewise in one of many different senses, as a form of power-against. Starhawk’s ‘power-over’ is just one class of the latter: there are others – and we’ll need those to make the model complete enough to make sense in the real-world.

However, even in this model, we still have no definition of what power actually is…

To resolve that gap, we might note that in physics, the term ‘power’ in effect represents ‘the ability to do work’ – with the term ‘work’ formally defined as ‘the rate at which energy is expended’. If we transfer that into human terms, then power is the ability to do work.

The catch is that that definition could just as easily apply to slavery – ‘arbeit macht frei‘ and all that. So we’d best urgently add at least one rider to that definition: Power is the ability to do work, as an expression of personal choice, personal responsibility and personal purpose.

But if power is the ability to work, then what is ‘work’? The short answer is that work is whatever people do – or, as per that physics definition of ‘work’, it’s any way in which people choose to expend their energy. So digging a ditch is work; solving a technical problem is work; but so too is building a connection with someone, or calming a fractious child, or reclaiming hope from despair. Power is the ability to do work, as choice; and work is whatever people choose to do.

To get a bit more clarity on what work actually is, and also link it back to our other domains in enterprise-architecture, we can also usefully do a crossmap here to the asset-dimensions in Enterprise Canvas:

- physical – working on ‘things’, anything tangible or physical

- mental [‘virtual’] – working on ideas, concepts, problems

- emotional [‘relational’] – working on relationships with others

- spiritual [‘aspirational’] – working on personal meaning and purpose, sense of self, or relationships with ‘that which is greater than self’

Note that, exactly as with the asset-dimensions in Enterprise Canvas, most real contexts involve work on multiple dimensions at once. Starhawk’s power-with, almost by definition, involves relational work, creating and maintaining connections between two or more people; and her power-from-within is, in essence, spiritual-work, working on one’s sense of self, meaning, purpose; so when power-with actually happens, it’s a process within which both relational-work and spiritual-work take place at the same time, in different ways for each of the parties in the interaction. In team-work all of the power-with interactions are going on at the same time as the mental and/or physical work of the overall team.

In short, all of those different forms of functional-power interweave with each other, all of the time. To make sense of a context, it’s often useful to gently tease apart – in conceptual terms, at least – all of those different threads of work and power: yet it’s essential to remember that in the real world they only work when working together. Divide-and-rule really doesn’t work here…

To reframe all of the above in Starhawk’s terminology: power-from-within is the ability to source and access human power from within the self, to do the work of the self, as an expression of personal choice, personal responsibility and personal purpose.

And power-with is the ability to assist each other to generate and access power-from-within, and to share that power with others, as an expression of shared choice, shared responsibility and shared purpose.

For suggestions about the nature of power-against, we could perhaps use the categories in a framework such as the Duluth Model, which in essence provides us with a catalogue of what goes wrong in interpersonal and wider relationships:

- coercion and threats

- intimidation

- economic abuse

- emotional abuse

- using privilege

- using isolation

- using children

- minimising, denying and blaming

There are also two other common categories of power-against that, for some unknown reason, are absent from the original Duluth model:

- sexual abuse

- third-party abuse

(Third-party abuse occurs where someone uses misinformation or misdirection so as to set up ‘authority-figures’ and other third-parties to enact some form of abuse or violence on their behalf against some Other. It’s a particularly difficult and complex form of abuse to identify and resolve, because the initiating-perpetrator of the abuse is concealed or purports to be a ‘victim’, and, very often, the real victim is falsely purported to be the ‘perpetrator’ of some other misdeed or abuse. In forms such as rumour-mongering, for example, it’s the one type of abuse of which school-students report as being most afraid.)

When we look at that catalogue of woe, perhaps the one common factor throughout is that in all too many contexts, social ‘power’ is presumed to be the ability to avoid work – rather than the ability to do work. Which explains a lot…

The first point about ‘power is the ability to avoid work’ is that it doesn’t work – literally so. Since its definition of ‘success’ is that work is avoided, then by definition the more ‘successful’ it is, the less actual work gets done.

More worrying is that, as a delusion, it’s extremely addictive. Because of the deep-seated belief that it ‘should’ work, it’s therefore applied more and more as less and less successful outcome is achieved – particularly when the respective work can only be done by the self, such as in all forms of spiritual-work (‘sense of meaning and purpose’, etc).

It also leads to a more worrying social-delusion that power and status should pertain proportionally to those who do the least work, or who most entrap others into doing the work on their behalf. Hence, all too often, dysfunctional business-hierarchies, or hierarchies of all kinds. Hence, too, the social reality that the closer one gets to doing effortful physical-work, the less one gets paid – of whom the extreme are home-parents and other carers, who do some of the hardest work of all, yet in our insane money-based economics are deemed to be ‘worth’ almost nothing.

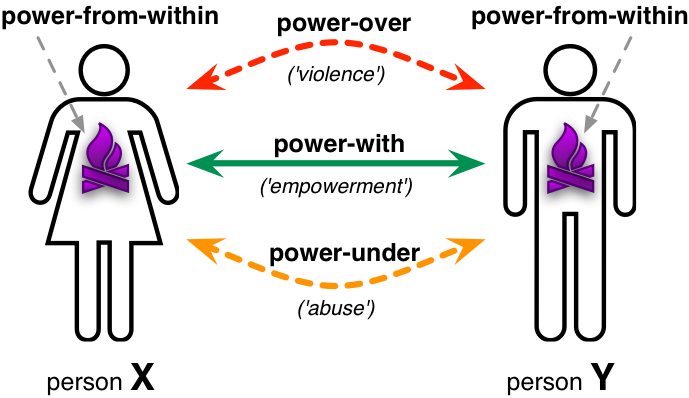

If we explore those Duluth Model categories in more depth, it becomes clear that there are two quite distinct themes going on within all of those forms of abuse, but interweaving with each other in different ways. To maintain the alignment with Starhawk’s model, we could describe these two forms of power-against respectively as power-over and power-under.

Unsurprisingly, this ‘power-over’ is close to the implications of the classic ‘pie-slice’ power mode: it’s actively dysfunctional. For the purposes here I’d define it as follows: power-over is any attempt, by anyone, toward anyone, to prop Self up by putting any Other down. (There’s also a ‘lose/win’ version, putting self down to prop others up: that’s often thought of as socially praiseworthy, but in reality it’s ultimately every bit as dysfunctional as the ‘win/lose’ version.) The colloquial term for power-over is ‘violence’. Notice the key point about “from anyone, to anyone”: ‘the Other’ might well also be Self – such as beating myself up for failing to get this written exactly on-schedule.

‘Power-under’ is a bit more subtle, not least because, for the most part, it’s passively dysfunctional – it’s more in what isn’t done, rather than in what is. For the purposes here I’d define it as follows: power-under is any attempt, by anyone, toward anyone, to offload responsibility onto the Other without their engagement and consent. (As with power-over, there’s also a ‘lose/win’ version, taking on responsibility from the other without their engagement and consent – and again as with power-over, it’s often seen as praiseworthy but in fact is equally as dysfunctional as the ‘win/lose’ version.) The colloquial term for power-under is ‘abuse’. Notice again the key point about “from anyone, to anyone”, because again ‘the Other’ may actually be the Self – such as in my trying to put off writing this until tomorrow.

Collectively, power-over and power-under are aspects of what I described in that summary earlier above as ‘power-against’.

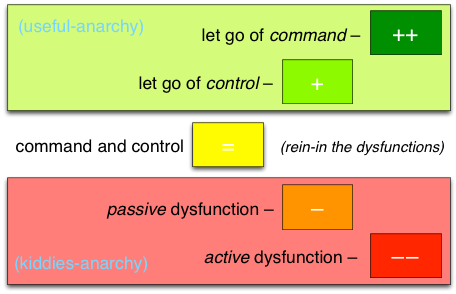

We can also usefully crossmap all of this onto the SEMPER model of power and effectiveness in the workplace:

- ‘++‘: ‘individual as wholeness-responsibility’ – outcome of full power-from-within, usually grounded in support of collective power-with

- ‘+‘: ‘organisation supports individual’ – collective power-with

- ‘=‘: ‘command and control’ – reins-in the dysfunctions sufficient to leave some space for self-generated power-from-within, without power-with

- ‘–‘: ‘passive-dysfunction’ – individual and/or collective power-under

- ‘––‘: ‘active-dysfunction’ – individual and/or collective power-over

When fully supported by mutual power-with, constructive power-from-within drives an upward-spiral into ever-greater achievement – although technically a form of useful-anarchy, since it’s always ultimately an expression of the individual as individual. By contrast, the huge danger of power-against is that, in any form, they can become deeply addictive, driving a downward-spiral into full-blown ‘kiddies’ anarchy’.

Power-against can also occur in mutually-interactive forms that are oddly symmetrical and balanced – even if at times only a balance of terror, of mutual dysfunction. For example, what we too often see happening in dysfunctional-relationships is a classic codependent pairing, where each of the parties swap back and forth between the relative roles of ‘perpetrator’ and ‘victim’, continually switching from one power-against tactic to another, in a wildly unstable tug-of-war: and yet the overall relationship remains relatively stable – so much so that if either party tries to pull out of the mess and end the mutual-dysfunction, the other will usually put renewed effort to drag them back in.

In that sense, we’d need to replace the ‘power-over’ part of Starhawk’s power-model with something more like this:

Note, though, that whilst the parties in a dysfunctional ‘power-against’ relationship might be respectively male and female, as per that graphic above, they could just as easily be both male, both female, same or different ages, same or different cultures, even human and non-human once we start to look in more depth at relationships with animals and the like. It’s all about power – either power-with and power-from-within, ‘the ability to do work’; or power-against, power-over or power-under, the delusion of power as ‘the ability to avoid work’. Those are the only two choices – power-with, or power-against: and power-against doesn’t work – for anyone.

What we end up with here is a power-model that works, that makes practical sense, and whose symmetry makes it much more defensible both from a systems-thinking perspective and in terms of real-world evidence too. We could summarise it visually with a kind of ‘traffic-light’ colour-coding as follows:

There’s one more point we need to explore before we move on, though, and that’s the relationship between power and responsibility. To put it at its simplest, if there’s no responsibility, there’s no power. This is actually where the whole concept of ‘rights’ falls apart. In terms of that power-model above, the only way in which people could validly be assigned the exact same social and legal power as others is if they have the exact same legal responsibilities. Anything less than that, in terms of responsibilities, would imply some form of structurally-imposed power-under on someone’s behalf – inevitably triggering off a perceived ‘need’ for some form of power-under or power-over to defend and balance against that power-under, and onward into a codependent downward-spiral. In short, Not A Good Idea…

So whilst the concept of ‘rights’ might seem to make sense as a solution to many social ills, the reality, as I’ve explained in various posts here, is that they just don’t work. They combine a declaration of a desired outcome – yet absent of any indication of how the heck it can be achieved – with an assertion of absence of responsibility: it’s my right, others alone are responsible for giving it to me. This is true of all purported rights, but it’s especially problematic when the rights are inherently asymmetric – pertaining to only one group – because then the excluded group are arbitrarily assigned all of the responsibilities but none of the ‘rights’. Again, structurally-imposed power-under, hence, again, Not A Good Idea…

In effect, what ‘rights’ really are is a tame-problem ‘solution’ to a wild-problem context – and that always causes the respective problem to change from merely complex to deeply-intractable ‘wicked’. To get the desired outcomes of the respective ‘rights’, we need to apply a reframe, to restructure ‘rights’ as mutual interlocking responsibilities. (See the post ‘An architecture of responsibility‘ for a worked example regarding ‘rights of possession’.) A typical reframe for this would begin somewhat as follows:

- Identify the desired outcome for each of the respective ‘rights’ (for example, apply a Five Whys or suchlike to identify the real deeper needs behind the respective ‘right’)

- Identify the mutual responsibilities and interlocks of actions, decisions and behaviours that would enable the respective outcome in real-world practice

- Identify checks and balances that would ensure that the responsibilities are perceived as ‘fair’ to all respective parties

The key problem, and danger, with so much of the ‘rights’-discourse is that it’s almost entirely focussed on the individual – not the relationship between Self and Other. It’s often absent of any actual notion of mutuality or fairness across the whole: instead, what we too often get is a one-sided assumption of individual ‘entitlement’, and damn everyone else – “I have rights, you have responsibilities” – all powered by vast amounts of self-dishonesty and Other-blame. Which is precisely why the ‘rights’-discourse is still going nowhere at present – and is unlikely to go anywhere further until those issues are honestly faced. Which is kinda sad, really, because that kind of mess hurts everyone – and yet, with quite a small amount of real systems-level thinking, the structural aspects at least of the mess could be resolved with very little effort at all.

If we want to resolve those all-too-real problems around power, for everyone, we really do need to do better than what’s been done so far. But I do hope that that power-model above can indeed provide something useful to help in that. Over to you on that, anyway.

Practical applications for enterprise-architecture

Probably the most useful point from this session is to take those definitions around power, and apply them to everyday contexts. A refresher on those definitions again:

- power is the ability to do work (or, in a human context, extended as ‘the ability to do work, as an expression of choice, responsibility and purpose‘)

- delusory-‘power’ is ‘the ability to avoid work’

- power-from-within is the ability to source and access power from within the self (in general, applicable only to humans or other animals)

- power-with is the ability to assist each other to generate and access power-from-within (alternatively, the ability to do work, as an expression of shared choice, shared responsibility and shared purpose) (mostly human and other animals, but the assisting party may be IT and/or machine in some contexts)

- power-over is any attempt, by anyone, toward anyone, to prop Self up by putting any Other down

- power-under is any attempt, by anyone, toward anyone, to offload responsibility onto the Other without their engagement and consent

And a perhaps-useful reminder:

- ‘rights’ will need to be restructured as interlocking mutual responsibilities

At the first level, apply these solely to technical concerns, such as interfaces between systems:

- What is the work to be done?

- What energies, assets and resources will be needed for that work to be enabled and enacted?

- Who or what has the power – the responsibility or ‘response-ability’ – to do that work?

- Where do any structures risk creating a context where one or more systems prop themselves up by putting others down – such as by demanding arbitrary priority, or creating a deadlock?

- Where do any structures risk creating a context where one or more systems attempt to offload responsibility onto others without their engagement or consent – such as in a mission-critical control-system left to run inappropriately ‘open-loop‘?

- What mutualities and interlocks are required to ensure that the system overall runs in a balanced way that is ‘fair’ to all parties in the interaction?

- Who or what decides what constitutes ‘fair’ within the design and operation of the system?

Apply these questions also to broader-context concerns. For example, what happens when we reframe security and access from ‘rights’ to mutual interlocking responsibilities? What are those responsibilities? What are the mutualities and interlocks that make it work for all parties? What’s needed to maintain the balance of responsibilities across the whole domain? The ‘Validation‘ model in Enterprise Canvas may also be helpful for this.

Power-issues of many different kinds are obviously also utterly central to most enterprise-architecture work, especially once it moves beyond a strict IT-centric domain. The checklist above applies in exactly the same way, but please, please, use that checklist with care. In particular, do not try to use it in the complexities of human contexts without having first had a significant amount of practice on relatively straightforward technical-systems at progressive levels of complexity, from Simple to Complicated to Ambiguous to Not-known. And although power-problems in the social context can be bad enough, the similar power-dysfunctions in the workplace too often manage to be even worse: in the business-context, the term ‘kiddies’-anarchy’ may gain all too real a meaning… Enterprise-architects need to tread carefully around the power-issues in business and elsewhere, because the wrong kind of carelessness there can be a career-killer, or worse. You Have Been Warned, please?

For a practical example of how to tackle this, consider the balance of responsibilities, mutualities and interlocks needed across the entire set of investors and beneficiaries in an enterprise: the ‘Investors‘ model in Enterprise Canvas may be useful as a crosscheck here.

You may also find useful the ‘manifesto’ reference-sheet on power and responsibility in the workplace, that I wrote to accompany my book Power and Response-ability: the human side of systems – the ‘manifesto’ is a free download in PDF format from the Tetradian Books website.

Leave a Reply