Change-mapping: Plan and Action

In the Change-mapping method, what exactly is Action? Doesn’t action happen everywhere?

The short-answer to that second question is actually ‘Yes’ – action does indeed happen everywhere.

In which case, you might ask, what’s the point of having Action as a distinct domain in Change-mapping?

And the answer to that question is actually also the same as the answer to the first question above. Yet to make sense of that answer, we may need to look in a rather different way at what we might think of as ‘action’.

The key to that different understanding is fractality – the same pattern repeating in ‘self-similar’ ways at any or every scale. That fractality that makes it possible for Change-mapping to deliver on its promise that it works the same way everywhere – any scope, any scale, any content or context, any stage of implementation, whatever.

Yet it’s easy to miss a subtle point here: that same fractality also applies within each Change-mapping ‘Mission’, or task. If we think of a task as shown in a Gantt-chart, it’s an activity or set of activities clustered together as a single chunk – one that we’d typically represent on the Gantt-chart itself as little more than an empty box with an appropriate label. For simplicity here, let’s call it ‘theTask‘:

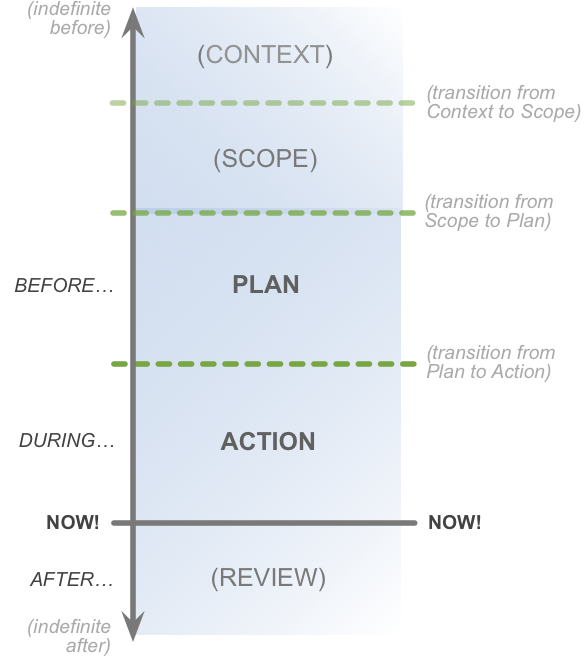

In Change-mapping, though, we’d split that undifferentiated chunk of activity into a distinct set of related ‘mini-tasks‘. In principle we can split the activity any way we like, but for here it’s simplest illustrate this with Change-mapping’s default method, the CSPAR set – Context, Scope, Plan, Action, Review. If we do that, then that empty box of theTask would now look something like this:

This is where the fractality’s recursion kicks in – and yes, if we’re not careful here, this could move rapidly into “my brain ‘urts…” territory, where nothing makes sense at all. To make sense of how this works, we must keep track of where we are in that recursion, every step of the way. Yet if we can keep track of what’s going on here, there’s a sudden shift in perspective where it does all make sense – I do promise you that.

So here’s what actually happening in the recursion:

— What we’re calling ‘theTask‘ is actually a chunk of Action – a set of activities that change something. (It’s true that there are some special cases where no actual activities take place, and/or where nothing actually changes, but let’s skip over those special-cases for now.)

— We’ve split the Action of that task called theTask into five ‘mini-tasks’, called Context, Scope, Plan, Action and Review. In effect, these mini-tasks are the steps of the work-instructions for the Action of theTask, as shown in the graphic above (and, recursively, as the ‘micro-tasks’ that form the work-instruction-steps in the left-hand half of the Action mini-task in ‘the Task’ – we’ll see more on that in a moment).

— Each of those mini-tasks – Context, Scope, Plan, Action, Review – is itself a task in its own right. Which means that they too each have their own Context, Scope, Plan, Action and Review, as their own ‘micro-tasks‘.

— In turn, each of those micro-tasks is likely to call for context-specific methods – for example, methods specific to Context, Scope, Plan and Review, plus whatever methods we build or use for the respective Action – that we could describe as ‘sub-micro tasks‘.

And yes, the nesting of tasks-within-tasks-within-task could repeat almost indefinitely: “it’s tasks all the way down”.

You’ll also note that, given the recursion, each one of those tasks-within-tasks-within-tasks has its own Action mini-task – which is why we see Action everywhere. The point here, though, is that we also need to see Context, Scope, Plan and Review everywhere, too – because that’s how we ensure that we do the right things right, everywhere, and learn from everything that we do.

And yes, all this recursion can make that hard at times…

Yet there is a way in which we can clarify the crucial distinctions in play here. It comes in two distinct parts – one about what the respective Action does in each case, the other about relationships in time. Let’s deal with the Action-focus first.

There’s another twist here that again is easily missed. We typically show the CSPAR set as if they’re steps in a step-by-step process:

In a sense, yes, it is step-by-step in that way. Sort-of, anyway. But only ‘sort-of’…

In reality, that apparent sequence exists only because of the dependencies between each of those domains: we need to know something about Context in order to define Scopes, we need to know Scope-boundaries for any Plan, we need to be clear about the Plan and preparation before we start any Action, and we need the results of any Action, and all the setup and Scope and Context, before we can do the respective Review. There may well be quite a lot of back-and-forth between the domains as details get fleshed out and call for a rethink of what happened earlier, which would break up the sequence somewhat. And there can also be multiple instances of each domain: a context may spin off several Scopes, a Scope may require multiple projects or Plans, and each Plan my have multiple Actions, each of which will require their own Review. In that sense, no, it’s not just a straightforward single-pass linear sequence: it can often be a lot more complex than that. Yet the overall flow does line up well with that pattern – which is why it’s simplest to show it that way.

To see in somewhat more depth what’s actually going on in Action, let’s use the same ‘theTask‘ graphic:

Each of those blocks inside theTask is a sub-task, which we’ll label as ‘theTask:Context‘ and suchlike. Yet each of those blocks represents a different type of action – doing different types of sub-tasks, using different tools to carry out different types of activity, to collect different types of information, to be used in different ways, but all supporting that overall goal of ‘do the right things right, and learn from everything’. Given that we can then summarise the respective Action in each case as follows:

- in theTask:Context, the Action is to check that the big-picture context for theTask is properly understood, and, if not, find the respective Context-type information that’s needed to bring that clarity

- in theTask:Scope, the Action is to check that the respective scope for the intended Action is properly understood, and, if not, find the respective Scope-type information that’s needed to bring that clarity

- in theTask:Plan, the Action is to identify the activities needed to prepare for the activities in the main activities of the task (i.e. in theTask:Action), and do any child-tasks (‘micro-tasks’) needed for that setup

- in theTask:Action, the Action is that we enact the work-instructions set up in theTask:Plan, within the boundaries of the scope set up in theTask:Scope, and in context of the big-picture identified in theTask:Context, and collect any information needed for the subsequent review

- in theTask:Review, the Action is that we do a review of what was done in theTask:Action, to identify benefits-realised and lessons-learned in relation to the plan from theTask:Plan, the scope from theTask:Scope, and the big-picture context from theTask:Context

So yes, there’s Action everywhere – but that Action is always in context of the respective Context, Scope, Plan and Review. That’s how it works as a unified whole. But that’s also why we do need to keep track of the recursion, such that every Action does always take place in relation to the respective Context, Scope and Plan, and assessed by the respective Review.

That’s one part of how we can make sense of what’s going on here – the part about what the respective Action does in each case.

The other part is about relationships in time. This uses the same idea of sequence as before, but builds upon a somewhat different insight: that every Action occurs at a point in time called ‘Now’. In effect, ‘Now’ is where the Action is. In which case, everything else that’s related to that Action either happens before that moment of Now (Context, Scope, Plan) or after that Now (Review):

This may seem obvious at first, but it provides some very useful insights:

— If an Action takes place in the Now, then in turn any given Now has some kind of Action happening at that moment in time. (In this sense, inaction is still an Action – just one in which nothing visible is happening…) Yet since there’s an Action happening, that implies that there was a task of some kind (task or sub-task or mini-task or micro-task or whatever, at whatever level of nesting) that was in progress at that Now, that moment in time. In which case, what was the respective task, and its ‘location’ relative to all others within the overall map of change? What was the respective Plan for that Action, its Scope, its Context, its purpose? What Review will we need to do, to learn from what we’re doing (or not-doing) right now? If we don’t have answers to those questions, maybe we should…

— Whenever we’re working on Context, Scope or Plan, the respective Action for which we’re developing each of these will take place in some future Now. As described earlier above, yes, there’s some kind of Action taking place within each of the respective Context, Scope or Plan, and the Action there is taking place within its own Now – but it’s not the same Now as that future-Now for the Action for which we’re developing the respective Context, Scope or Plan. It’s really important to keep track of the nesting here, and to not mix up all these different moments of Now!

— If we’re in Action, and we have to jump back to Plan to rethink what we’re doing, time itself moves on whilst we’re doing that. A Plan is always for a future Now and its future Action.

— Conversely, a Review always takes place after the Now of the respective Action. Again, by the time we get to the Review, time itself has moved on from that Now – so we can’t go back in time to change the previous Action or its outcomes. All we can do is learn from the outcomes of that Action, and move forward to apply that learning in some future, different Action.

— If we’re gathering information for a future Now, we’re in a Context, Scope or Plan sub-task for the current task. Conversely, if we’re gathering information about a Now that’s in the past, we’re in a Review sub-task for the current task. When the time-focus of the Action is the same as the same as the present Now, we’re enacting the main activity required for the current task – the ‘parent-task’ for the current CSPAR set, such as the theTask of our example. We can therefore use the time-focus of the current Action to help us identify the task or sub-task to which that Action relates.

So those are two different ways to differentiate Action, and link it to the respective task and sub-task:

- identify what type of information and activity is needed at each moment – Context, Scope, Plan, Action, Review or whatever

- identify which ‘Now’ – and hence task or sub-task – to which that Action relates

I hope that’s useful – that this whole fractality of Action now makes more sense than it did? Or maybe it’s made it even more confusing than it already was? Over to you for your comments, anyway.

Good stuff Tom!

Would be great to see visual of this:

“If we’re gathering information for a future Now, we’re in a Context, Scope or Plan sub-task for the current task. Conversely, if we’re gathering information about a Now that’s in the past, we’re in a Review sub-task for the current task. When the time-focus of the Action is the same as the same as the present Now, we’re enacting the main activity required for the current task – the ‘parent-task’ for the current CSPAR set, such as the theTask of our example. We can therefore use the time-focus of the current Action to help us identify the task or sub-task to which that Action relates.”