Three months to go! – an addendum

Yes, I’ll admit it: that whole ‘retirement’ thing in the previous post was a euphemism for “Goodbye, ‘enterprise’-architecture, and (no) thanks for all the (lack of) fish”. Oh well.

Yet where does this take us?

Over on LinkedIn, Michael Cooke kindly asked if there was a conventional job for me in enterprise-architecture or the like. In essence, unfortunately, the real-world answer is ‘No, there isn’t’. I learnt that point the hard way. I’ve also found out the hard way that I’m considered too honest for probably any of the mainstream big-consultancies; for similar reasons, I’m apparently unacceptable to academia too (again, first-hand experience there).

Why not regular EA roles? Well, ageism plays its part – which is daft, as architects of any stripe don’t really get into their stride much before their fifties. And yes, almost all paid-roles in ‘enterprise’-architecture at present are actually for low-level IT in whatever the current fad may be – for which I’d likely be too far out of date, and hence classed only as a junior, on half the pay at best. My real skillset is as a generalist, cleaning up the mess created by narrow-focus specialists: but there are no paid-jobs for generalists, and instead we’re invariably treated as third-grade failed specialists, at half the pay again. In other words, it’s likely that the best that I can expect to earn from any current ‘enterprise’-architecture role would be around a quarter or less of what the IT-obsessives get, for work that I’m not suited for, and would be as stressful as hell because I’ll know that all I’d actually be doing is helping to make things even worse than they already are. In short, Not A Good Idea… thanks-but-no-thanks…

So whilst there’s a huge need for what I and people like me do, there’s a vastly greater ‘anti-want’ for it. And right now there seems to be no way round that trap. In which case, the only feasible option for me is to walk away.

Great…

And yeah, people like me don’t retire. Not ever. But we do need meaningful work. Yet, to be blunt, ‘enterprise’-architecture is now so crippled by cluelessness and the like that it will probably take at least a generation to even begin to be recoverable. And at my age, I really can’t afford to wait around for that any more. Sorry, but no: I literally have better things to do with what little life I have left.

What’s holding us back is that so-called ‘enterprise’-architecture has become a really good example of how not to do ‘the architecture of the enterprise’.

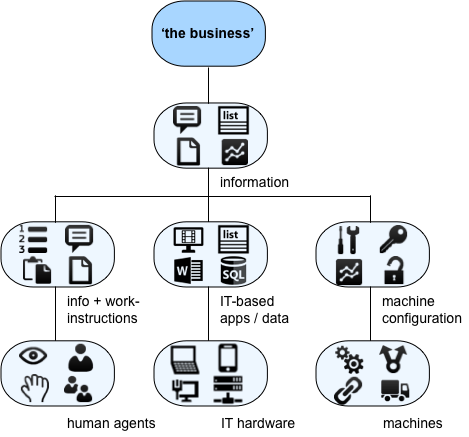

To illustrate the point, here’s a typical scope for IT-infrastructure architectures:

It is a fair enough overview for an architecture if and only if the sole concern for that architecture is IT-hardware, and where ‘the business’ is the management and organisation of IT itself – in other words, where the ‘enterprise’ in question is something like as in Open Group’s concept of IT4IT. Yet if the actual architecture has any broader concern – in fact any scope other than solely IT-infrastructure alone – then that kind of overview is not sufficient. At the very least, it needs to provide adequate hooks to every other concern in scope. If we don’t do that, the architecture will cause fragmentation across the whole, and hence will inevitably fail as an architecture.

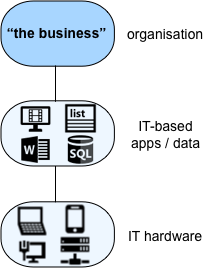

In short, whilst we might describe the overview for an IT-infrastructure architecture like this:

…that would only be a tiny subset of an architecture-overview for an organisation in context of its overall business-enterprise, that’s more like this:

The actual pattern we’re dealing with here is that, whatever our current focus for the architecture may be, we need to put that focus at the centre of that pattern, like this:

Hence, if our focus is ‘the business’, and we look downward to the architecture of how the information-needs of the business might be implemented, the requisite scope would not be a potentially-arbitrary IT-specific subset like this:

…but would necessarily need to be something more like this:

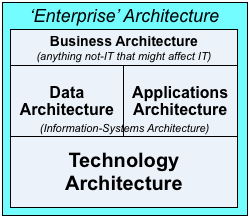

So, for any architecture, there are huge dangers that can and do arise if anyone confuses a subset for the whole – the assertion that the subset is the whole, arbitrarily excluding everything else that might actually need to be in scope. So if, for example, IT-centric assumptions about scope dominate the picture, we risk ending up with an assertion that the entire and only permissible scope for enterprise-architecture is this:

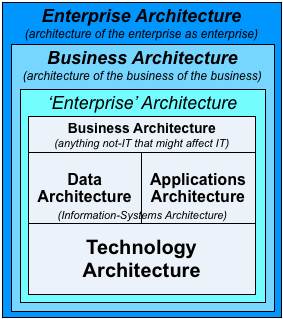

….which, whenever we attempt to use that frame for anything other than IT-hardware architecture, leads inevitably to a farcical black-joke that would look like this:

…in which ‘Business Architecture’ is both ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ of ‘Enterprise Architecture’, which in turn is itself both ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ of ‘Business Architecture’.

Huh???

Yeah, it’s an absolute howler of a mistake. A scope-error so blatant, so self-evidently wrong, that it seemingly should be obvious to everyone, right from the start.

So surely no-one would be so foolish as to build an entire ‘enterprise’-architecture framework on that mistake, would they? But yeah, that’s exactly what they did.

Surely no-one would go on to build an architecture-notation on top of that mistake, would they? But yeah, that’s exactly what they did.

And please, surely no-one would get it so wrong as to build a reference-architecture for healthcare on that mistake, would they? But yeah, that’s exactly what they did.

A complete failure of architecture-of-the-architecture, a mistake that no-one should ever make. And yet they’ve made that same mistake – continue to make the same mistake – over and over again, time after time.

Yeah. It’s that bad.

All of the hard-evidence we have points to this mistake as a direct cause of architecture-failure. I’ve hammered and hammered on this obvious point for almost two decades now, maybe more: and yet, for the most part – if with some much-valued exceptions – it’s mostly fallen on deaf ears. Or rather, ‘deaf ears’ of the ‘no-I’m-not-listening-I-can’t-hear-you-I-can’t-hear-you-I’ve-got-my-fingers-in-my-ears-nah-na-nah-na-nah’ kind. And yet every time, after every warning, they still go straight back to making the same mistake, all over again. And then wonder why it doesn’t work.

Yeah, really: that bad…

The whole miserable mess is probably best summarised in a verse from that old song by Roy Harper:

“You can lead a horse to water,

but you’re never going to make it drink;

you can lead a man to slaughter

but you’re never going to make it think…”

Sigh.

The bleak, blunt fact is that few if any of those IT-obsessives who call themselves ‘enterprise-architects’ are doing anything resembling a real enterprise-architecture. Given how fundamentally-flawed the frameworks are, it’s doubtful if they’re even doing much of a real IT-architecture, either. All that they’re actually doing is actively preventing anyone else from doing that much-needed work. And yet they cling to the label of ‘enterprise-architect’ like a toddler with safety-blanket. God only knows why…

So yeah, I’m moving out of that mess. Any attempt to engage with those people brings me nothing but frustration, angst, insults, and even worse negative-income than I started with. So why bother? What’s the point? None at all.

Goodbye, ‘enterprise’-architecture, and no thanks for all the lack of fish.

Bah.

If that’s what I’m moving from, what am I moving to?

Don’t worry: I’m still deeply committed to the architectures, principles, processes and practice of whole-enterprise architectures. We need architectures that actually do work across the whole enterprise – and we’re going to need them even more as the big-changes coming our way start to hit hard Real Soon Now.

Yet even whole-enterprise architecture has only ever been one part of what I’ve done, and do. My real work is on how people learn skills – get better at learning new skills, and applying them in better ways, too.

And yeah, I’ve been doing that work for a long time. At least half a century by now; arguably more.

As John Morris noted, you’ll see on that photo of my bookshelf, in the previous post, that there are a fair few books that I’ve written over the years on dowsing (US: water-witching). The first book I had published on that topic – way back in 1976, and still in print every year since then – was actually the test-case for my formal research on ‘design for the education of experience’. And the real core-concept behind that is this:

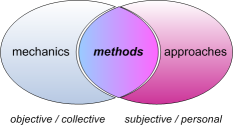

Almost all teaching starts with the assumption that all we need to do is start from method, and that the methods we teach are the same for everyone. In reality – and especially for skills – that’s completely wrong. Instead, method arises from how we combine the ‘mechanics’ of the issue – that which is the same everywhere, for everyone – and the ‘approaches’ to the issue – that which is context-specific, that which is not the same for everyone and/or everywhere.

We can also extend that point a bit by adding drivers into the picture – purpose and suchlike – but the underlying principle is essentially the same::

So why dowsing? Well, it was traditionally regarded as all but ‘unteachable’; and there were a morass of randomly different methods, each of which purported to be ‘the only way to do it’. The reason I was interested was that it’s very close to what I’d call a ‘pure skill’. For most skills, there’s a vast amount of mechanics that we’d need to learn: technical information, body-knowledge and so on. But for dowsing, there’s only a tiny amount of underlying mechanics – in fact I routinely got people to learn that part in a couple of minutes. All of the rest was how people approached the issues and context, to develop their own method. In that sense, the skill of dowsing gave an almost perfect test-case for focussing on the approaches – though also explained why getting the methods right for each person can be so much harder than it looks.

(It’s actually exactly the same issue about how to use so-called ‘best-practices’ in business and elsewhere: separate out the mechanics of the ‘best practice’ from the original approaches – the usually-unacknowledged assumptions about context; identify local equivalents for those contextual concerns; re-adapt to the local context; and only then do we adopt the resultant context-specific method.)

That’s the skill-part. The other part was a simple insight about connecting across different types of context. The key was about how we can use fractality to give us core ‘best-practice’ methods that work the same way everywhere: every type of content or context, every scope and scale, every stage of implementation, every timescale and so on. And a tool that works the same way everywhere not only gives us consistency across the whole, but also vastly reduces the number and complexity of new tools that we need to learn as we switch between domains. That’s what makes possible a true ‘architecture of the enterprise’; that’s why a crass narrow ‘IT-architecture-pretending-to-be-enterprise-architecture’ is so problematic, because it actively blocks access to that kind of ‘architecture of architecture’.

And once we add into the mix all the work I’ve done on power and responsibility, on business-change, on sensemaking, self-observation and much, much more – well, we have something that might actually work, in the exact same way that IT-centric ‘enterprise’-architecture can’t and won’t.

Which brings us back to fractality again – because it gives a different way to tackle change. Big changes are big and scary: too hard to face, often, because they’re so big. But fractal methods that work the same way everywhere: what that really means is that we can use the same methods at every scale, both small and big. If we get the practice in on the small changes, that’ll help us get ready for the big ones – and they stop being quite so scary. With fractal methods, and a consistent way to create context-specific methods, we do have a way to those otherwise impossibly-huge challenges that are coming our way, at a truly global scope and scale.

That’s what I want to work on.

Starting small. Putting everything into practice. Starting small. Providing space for others to learn their own way of working.

That’s the legacy I’d like to leave behind.

If that interests you, well, yeah, let’s keep talking. Keep doing, together. That’s what really matters here.

But the sad, pathetic farce that is most so-called ‘enterprise’-architecture? Nah, not interested. Not really. Not any more. Too many years wasted; too much of ‘the absence of fish’. It’s time for me to go fishing elsewhere.

A true depiction of the realities we face Today. The more the discipline has attracted comments from “system thinking” guru’s, the more doubt is shed on the principles that have been put in place over years of blood, sweat and many tears.

When discussion has devolved to the meaning of “Enterprise” we have now reached a point of no return. The advent of agile and the proposed infestation of it into all other organizational roles is just plain pathetic attempt by said guru’s to sell training courses which strangely enough are based on the very thing they are looking to replace.

I understand the frustration levels, and at our age the old saying of “if you don’t want to listen, then you must feel” seem relevant for interactions with said groupings.

Bah Humbug.

Yep. Agreed, Robert: “Bah Humbug” indeed.

Bah… 🙁

Tom:

I know you’ve been frustrated for some time about the state of EA and I don’t blame you. Somehow, it’s always been sandwiched between people’s desire to understand what to do and their antipathy toward actual work. One of the reasons I was initially attracted to the Architectural Thinking Association was the simplistic approach which, I felt, could still add value. I’m taking that simple palette of objects and applying it to ERM–it becomes the central barometer that signals change and initiates a risk-management process. Anyway, I digress.

I’m beginning to believe that enterprise architectures and structures will become increasingly ephemeral as the need to change rapidly actually accelerates. I think big EA will ebb as the cost/benefit of avoiding technical debt starts to tip toward ‘just do it, it doesn’t have to last that long anyway.’ Minimum Viable EA is where I think we’re heading.

Anyway, I will keep an eye out for what you publish in the new branch in the river you’re going to be floating down.

Best of Luck.

Many thanks, Howard.

On “I think big EA will ebb as the cost/benefit of avoiding technical debt starts to tip toward ‘just do it, it doesn’t have to last that long anyway.” – to me the problem is that what we might think of as ‘Big EA’ isn’t actually ‘big-EA’ at all, it’s a clunky incomplete version of high-level IT solution-design that never gets near actually delivering any solution. Which is why it not only fails, but leaves everything wide-open to the lethal mistakes created by the ‘just do it!’ crowd.

I’ll be going into this in some detail in my upcoming series on ‘How architectures fail’. The one-liner, for now, is that we definitely do need ‘big-EA’, but it’s both much broader in scope than current so-called ‘big-EA’, but also much simpler than most people seem to think. All that architecture needs to do is provide anchors and constraints for design – it’s not a big deal as such. But also note that design will fail if there’s no architecture in place to guide it: that’s precisely why ‘Agile’ approaches are so fragile, inefficient, ineffective and unreliable.

How we get most people to even begin to understand those utterly-essential points? I don’t know any more. It’s painfully evident that the ways that I’ve tried to do it, with straightforward logic anchored in real-world examples, it just doesn’t work: there’s a huge need for that, yes, but a also a vastly greater ‘anti-want’ for it. In that sense, I’m not helping, and mostly just making the resistance against much-needed change become even more entrenched. Hence probably best for everyone if I walk away and do something else for a while, to leave a space for someone better than me to do the job right.

The only real outcome from my attempts to bring about much-needed change is that it’s left me heading well into retirement-age, basically broke, right on the edge of actually homeless, with my productivity barely a tenth of what it used to be, no visible source of any income better than my current less-than-minimum-wage, and not much hope about anything. Literally fifteen years of my life thrown away, against an impenetrable wall of sheer stupidity. It hurts. Oh well.

Tom,

If I understand Zachman correct, any enterprise is an informational act – transforming between rows is about defining different representations of this informational act. Transforming from one row to another is not about having one row define the business from the perspective of its information needs transformed into another row supplying information technology serving that need. Transforming between rows is about different representations of the whole enterprise. In that sense, people and their work instructions, a physical car manufactured or information technology used are all technology being part of the same row ingrained in that informational act.

Not sure if the above brings any clarity into things but, if my understanding is correct, it has helped me to better understand the limitations/biases of TOGAF, ArchiMate and the alike. Your comments would be very much appreciated, you have always been an inspiration in pursuing my career so hoping you one way or the other will continue to help clean up the mess we are in…

Thanks, Magnus!

“If I understand Zachman correct, any enterprise is an informational act” – you probably understand Zachman correctly, but unfortunately his framework is crippled with several _fundamental_ errors (see ‘John Zachman and the curate’s egg’, http://weblog.tetradian.com/2015/06/18/john-zachman-at-bcs/ ). One of these errors is that an enterprise is _not_ “an informational act” – information is _part_ of it, yes, but by no means all, and also _not_ the underlying _human_ driver (see ‘Organisation and enterprise’ http://weblog.tetradian.com/2014/09/18/organisation-and-enterprise/ and ‘Organisation and enterprise as ‘How’ and ‘Why”, http://weblog.tetradian.com/2014/10/06/organisation-and-enterprise-as-how-and-why/ ).

In essence, Zachman-like layers add more detail as we get closer to the real-world (see ‘Services and Enterprise Canvas review – 4: Layers’, http://weblog.tetradian.com/2014/10/24/services-and-ecanvas-review-4-layers/ ). Note, though (as in that post), the layers need to extend both ‘above” _and_ ‘below’ the Zachman set: we need to extend ‘upward’ to an explicit concept of vision or purpose (as similarly specified in ISO9000:200 , by the way), and ‘downward’ past the point of action, to support learning _from_ action (otherwise we literally never learn from what happens in the real-world…).

We also _must_ include _all_ types of asset – _not_ solely information. (For more detail on that, see the post ‘Services and Enterprise Canvas review – 5: Service-content’, http://weblog.tetradian.com/2014/10/27/services-and-ecanvas-review-5-service-content/ )

I hope that helps somewhat, anyway.