Metaframeworks in practice, Part 2: Iterative-TOGAF

What methodology-frameworks do we need for broad-scope enterprise-architecture in a human-services government-department?

This is the second of five worked-examples of metaframeworks in practice – on how to hack and ‘smoosh-together’ existing frameworks to create a tool that will help people make sense of a specific business-context:

- Part 1: Zachman plus tetradian -> extended-Zachman

- Part 2 [this post]: TOGAF plus PDCA plus US-Army AAR -> iterative-TOGAF

- Part 3: Group Dynamics plus Chinese wu xing plus VPEC-T -> core Five Elements

- Part 4: Jung plus swamp-metaphor plus systems-practice plus Kurtz/Cynefin plus OODA plus many-others -> context-space mapping -> SCAN

- Part 5: Business Model Canvas plus Viable System Model plus extended-Zachman plus many-others -> Enterprise Canvas; plus Five Element plus Market Cycle -> Enterprise-Canvas dynamics

In accordance with the process outlined in the ‘Metaframeworks in practice‘ overview-post, each of these worked-examples starts from a selected base-framework – in this case, the TOGAF ADM (Architecture Development Method cycle) – and builds outward from there, to support the specified business-need.

Iterative-TOGAF framework

Business-need

In early 2007 I was part of a small team tasked with setting up an enterprise-architecture capability for an Australian state-level government department. Although the initial focus – as was still usual then – was around the department’s IT-systems, the business-context was in human-services: hence, as with the Australia Post example, we needed an approach to enterprise-architecture that was much broader than just IT alone.

At first our team was asked to develop the architecture “according to the Zachman methodology” – which didn’t in fact exist at that time. The only obvious alternative was the ADM (Architecture Development Method) from TOGAF (The Open Group Architecture Framework), version 8.1. But there were two important catches:

- its structure and content were almost entirely IT-specific: for example, we could use it to describe the IT-systems that community-workers would use, but not the work itself

- although it was described as ‘iterative’, in essence it described a process for full-scale IT-systems refresh that, in an organisation of this size, would typically take at least two years per cycle

What we needed was a methods-framework that could cover the whole of our enterprise-context, and that could be used consistently for any architecture review-task at any appropriate timescale.

Metaframework process

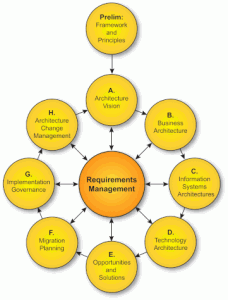

Start with the ADM from TOGAF 8.1 (the then current version):

As presented, the ADM cycle itself is strictly linear, but in theory at least, it can be made iterative and re-entrant via its links into ‘Requirements Management’.

From the mismatch described above, two key metaframework tasks:

- reframe to break out of the implicit IT-centrism – represented especially in the structure, content and sequence of Phases B, C and D

- reframe to enable use at any timescale

At a quick glance, the IT-centrism is primarily an outcome of over-specialisation of a generic pattern; hence probably the best concern to start work on is the timescale/iteration issue.

Apply the recursion/reflexion pair of systems-principles (“what is a smaller/larger-scale version of this?”) to confirm that the ADM is, in essence, a specialised version of a generic change-project lifecycle:

- identify the overall business-need (Phase A)

- establish the change-requirements (Phases B-D)

- identify options and develop detailed-design (Phases E-F)

- guide implementation and deployment of change (Phase G)

- identify benefits-realised and lessons-learned, to guide subsequent change (Phase H)

Select other iterative frameworks from the toolkit that resemble this type of pattern. One obvious choice is PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Act), for which compare and mismatch indicates:

- Plan the change – aligns with Phases B-D, early stages of Phase E

- Do the change – aligns with Phases E-G

- Check the change – aligns (or should align) with Phase H

- Act on the change (to start a new cycle) – aligns (or should align) with Phase A

The US Army’s AAR (After Action Review) process also suggests another rotation / compare / mismatch set that usually applies at much smaller scale:

- What was supposed to happen? – aligns with the plan in Phases B-D, and then Phase E

- What actually happened? – aligns with the execution of the plan in Phases F-G

- What was the source of the difference? – should align with the review in Phase H

- What can we learn from this, to do different next time? – should align with final stage of Phase H and core change-requirements in Phase A

Also, if the rotation cycle is to be fully iterative, recursive and reflexive – usable at any scale, often looping through itself at different scales – then we’ll also need explicit boundaries to identify when a phase-change or scale-change occurs.

Park all of those notes to one side whilst we address the other concern: breaking out of the IT-centric ‘box’.

To say that this v8.1 version of the ADM is IT-oriented is an understatement almost in the extreme – as illustrated by the number of steps described in each Phase:

- Phase B ‘Business Architecture’: 9 steps

- Phase C ‘Information-Systems Architecture’ (two groups: ‘C1: Data’ and ‘C2: Applications’): 16 steps

- Phase D ‘Technology Architecture’ (computer-related technologies only): 50 steps

In other words, computer-based systems are assigned more than six times as much attention as everything else altogether in the entirety of the business-context – which is a bit absurd given that IT would rarely account for more than 10% of total budget for almost any large organisation.

It’s also clear that there is a definite sequence to this: ‘Business Architecture’ is, in effect, “anything not-IT that might affect IT’; and ‘Information-Systems Architecture’ is, in effect, “anything IT-related that might affect IT-infrastructure”. The same themes and emphases recur throughout the ADM specification: everything is centred around IT, with everything else regarded as barely peripheral to that need. Clearly this will be far too unbalanced for use in any broader, non-IT-specific ‘architecture of the enterprise’…

The obvious option is to make Phase B much broader, and add further Phases in parallel with the ADM’s Phases C and D to cover the equivalents for other human- or machine- based processes (equivalent of ADM Phase C) and infrastructures (equivalent of ADM Phase D). I did try out that option, relabelling the respective Phases as ‘B: Business’, ‘C: Common’ and ‘D: Detail’. Yet whilst that would perhaps satisfy our immediate need, it would be difficult to make it truly consistent and generic across enterprises, and hence difficult to adapt for use elsewhere – in effect repeating the same problems as with the existing ADM, and in some ways even worse.

However, there is an alternate approach implied in the existing ADM. Each of the existing’ Architecture’ reviews – Phases B, C1, C2 and D – is split internally into the same four subsections:

- identify the overall need and scope (usually from the preceding Phase)

- develop an architecture-description for a specific time-horizon (usually the ‘to-be’)

- develop architecture-descriptions for one or more comparison time-horizons (usually the ‘as-is’ and any ‘intermediate states’)

- derive a gap-analysis from comparison between the respective architectures at each pair of time-horizons

(The outcome of all of the gap-analyses is then bundled together as the initial input for Phase E.)

In effect, this gives us a straightforward two-axis matrix: a variable number of ‘architectures’ and a fixed set of groups of activities within each of the ‘architectures’.

Hence the simplest solution here is to invert the matrix: the task-sets are applied to the overall architecture-scope. This would then give us a front-end for the ADM – the ‘Check‘ and ‘Plan‘ part of a PDCA-type lifecycle – that would be structurally-consistent for any architecture-scope and architecture-related change-requirement:

- Phase A: Identify business-need, scope and success-criteria

- Phase B: Develop desired architecture for the primary time-horizon

- Phase C: Develop (usually less-detailed) architecture for the comparison time-horizon(s)

- Phase D: Develop gap-analysis for each transition between time-horizons

The existing ADM Phases E-G would remain much the same as before, in the revised architecture-development method, because in essence it describes a conventional change-project management-process. The ADM specification is somewhat skewed to a ‘Waterfall‘-type development model, and might well need some adaptation to work with a more ‘Agile‘-type style, but that’s a problem that can be left for later as it’s outside of our own team’s scope.

The key remaining challenge is the structure of ADM Phase H, ‘Architecture Change-Management’. To be blunt, the original version doesn’t make sense even in its own terms: although the ‘environmental-scanning‘ review of the broader context is definitely useful, the tail-end of the lifecycle is far too late to be trying to decide on principles and governance for future change. Those latter themes should have been resolved right back at the beginning of the lifecycle, or preferably outside of and before any project-cycle takes place at all.

So for the redesign of Phase H, we return to those themes that we’d identified in the structures of other project-lifecycle review-patterns, such as the AAR and the ‘Check‘ and ‘Act‘ phases of the PDCA-loop. The simplest approach is to move all of the “how do we plan for change?” sections of the original right back into the Preliminary Phase setup, with a refresh during the revised Phase A of each iteration to establish success-criteria against which to carry out an end-of-iteration review in this revised Phase H. To do the review itself, we embed an expanded project-scale equivalent of the After Action Review process into this revised Phase, and explicitly link it to the setup of an future Phase A via documentation of the review.

Once this is done, the revised ADM is all but complete: the only remaining task is to find some way to mark explicit boundaries between Phases and between recursions. We can do that by specifying the artifacts or documentation that would mark those transitions:

- Preliminary Phase to Phase A: Architecture Charter

- Phase A to Phase B: Statement of work (for this current iteration)

- Phase B to Phase C: stakeholder-review for primary-architecture

- Phase C to Phase D: stakeholder-review for comparison-architecture(s)

- Phase D to Phase E: gap-analysis/requirements review

- Phase E to Phase F: solution-design review

- Phase F to Phase G: project-plan review

- Phase G to Phase H: project-completion architecture-compliance review

- Phase H to Phase A: benefits-realisation / lessons-learned plus context-review

The documentation can be any appropriate scale or scope: for a large-scale cycle it could well be a large document, but on a very small iteration it might only be a one-line entry on a wiki or project-management datafile.

The focus on transition-point documentation also helps to align (‘crossmap‘) the ADM with other frameworks in the ‘toolkit’ – particularly PRINCE2 project-management and ITIL service-management.

To make this work overall, the central region – ‘Requirements Management’ – assumes a key role as the central source and repository for all of the architecture information. It also needs to expand its role somewhat to include management not just of requirements, but of governance and governance-scheduling, and project models, glossaries, thesauri and probably much more, dependent on the type of business and the architecture-maturity of the organisation itself.

That’s where we stopped, for that specific business-requirement, though I’ve done various further tweaks over the years since then, using much the same metaframework-techniques as summarised above.

The complete revised-ADM is documented in my 2008 book Bridging the Silos: enterprise-architecture for IT-architects and, in abbreviated form, in a two-page reference-sheet as a free-download add-on for the book. It’s also used as the base architecture-method for the maturity-model based long-term architecture-development process described in my 2009 book Doing Enterprise-Architecture: process and practice in the real enterprise.

Originator-relations

I’ll admit I didn’t handle this one very well at first, perhaps because I was a bit too incensed at the mislabelling of IT-architecture as ‘enterprise’-architecture, and the problems that that caused for those of us whose business did not revolve primarily around IT. But Open Group were gracious enough about it to allow me to do several presentations on this at Open Group conferences over the years; and over those years the point about the need for a broader view of enterprise-architecture has taken root more generally- if still somewhat too slowly for my taste!

A much stronger sense of ‘agree to disagree’ these days, anyway – especially since there’s much more clarity about the two ‘enterprise-architectures’ and how they fit in relation to each other. So although you could say that I’m still somewhat of an Outsider relative to the IT-oriented orthodoxy, I’m certainly not regarded as ‘eccentric’ or ‘silly’ in the Open Group domain. That counts as a good result, I guess? 🙂

Applications

We used that amended-ADM throughout that Australian project, and I’ve used it extensively in most of my project-oriented enterprise-architecture work ever since. It really does work at every timescale: the shortest time I’ve done a complete documented cycle with it for a real architecture-requirement is just under an hour, but it still works just as well at the more conventional multi-year level too. It has also proved itself well-enough balanced and behaved to be reliable and robust at just about any level of recursion, as long as there is some means to keep track of the respective ‘recursion-stack’.

I know that it’s now being used by at least one TOGAF training-organisation as a worked-example of how to adapt TOGAF to specific business-contexts – particularly for those organisations whose business-models are not primarily focussed on information or IT.

The two-page reference-sheet has had close to 3000 downloads to date, and I know it’s been used either directly or as a guide for context-specific adaptation in quite a few places. In that sense, I think it could reasonably be described as a real success. 🙂

Lessons-learned

The main lesson-learned here was that consistency, symmetry and suchlike really matter for this kind of framework, particularly if it’s to be used at multiple levels of abstraction, granularity or recursion.

Also originator-relations do matter: I definitely do appreciate the way in which Open Group handled their side of this, though in the longer-term they’ve gained a lot out of it too.

—

Next worked example: an adaptation of the classic Chinese wu xing, or Five Elements, to model interdependencies across a whole enterprise.

Other than that, the usual request here: any comments or other feedback, folks?

Tom,

Another good article. Thank you

Thanks, Allen – glad it’s useful. 🙂