Enterprise Canvas – a military analogy

I’ll admit I often struggle to find easy ways for people to understand Enterprise Canvas and service-oriented enterprise-architecture – thinking in terms of services doesn’t seem to come naturally to many people. But the other morning, up came one of those right-upon-waking ideas that might just work for this: a military analogy.

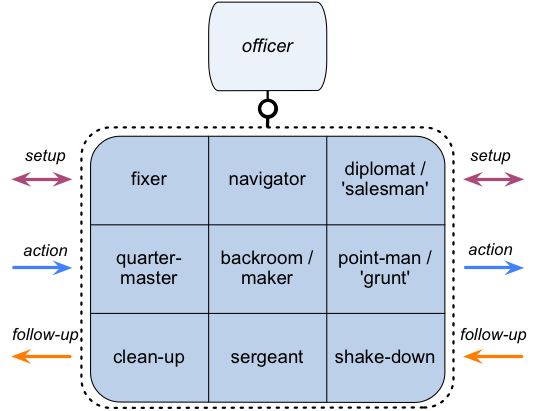

First, though, let’s put up a standard Enterprise Canvas mapping, this time of the central three-by-three matrix of ‘child-services’:

Imagine the classic platoon – a group of grunts, working their way out on active patrol out in the hinterland somewhere. If they’re British troops, it might have been in Afghanistan a year ago, or a century and more ago; or go back a couple of millennia to a Roman squad out the back end of Britannia – it doesn’t really matter. What does matter is that, at the squad level, armies have all worked much the same way forever, as a closely-coupled network of mutual services that we might summarise visually as follows:

These are roles rather than individual people, and we’ll often see the soldiers moving about between these roles over time: when it turns into a fire-fight, everyone is instantly a ‘point-man’, for example. But over time, natural tendencies will start to emerge, soldiers falling more often into one role than another, as a matter of habit if nothing else.

The guidance-services are kind of outside that dotted-line boundary of the platoon itself, yet connect it to the broader world. Although in the full Enterprise Canvas there are a fair number of these ‘external’ service-relationships, they’re here represented overall by one archetypal role:

— Officer [EC: Direction, Coordination, Validation] – connects the platoon to the big-picture, the overall vision and values, the ‘proper channels’ and suchlike

The inbound roles, on the left-hand or ‘supplier’ side, work on interactions coming ‘inward’ to the platoon, typically bringing stuff in that the platoon needs, or that come from the overall environment:

— Fixer [EC: Supplier-Relations] – searches around to find appropriate sources for what the platoon needs, or smoothes the way for things to be found

— Quartermaster [EC: Supplier-Channels] – receives inbound resources, and maintains and distributes them around the platoon as needed

— Clean-up [EC: Value-Outlay] – settles up, pays the bills, generally quietens things down again after the resources have been acquired or received

The value-construction roles, kind of ‘within’ the core of the platoon, identify what value is, create that added-value, and keep everything within the platoon itself moving towards delivery of that added-value:

— Navigator [EC: Value-Proposition] – identifies the pathway (literal or metaphoric) that would best achieve the purpose as outlined by the Officer (as ‘commander’s intent‘)

— Maker [EC: Value-Creation] – takes internal action to follow the pathway identified by the Navigator, using the resources obtained by the Quartermaster, locally guided by the Sargeant

— Sergeant [EC: Value-Governance] – provides local guidance and internal coordination, in context of the pathway identified by the Navigator, and in accordance with the overall intent identified by the Officer

The outbound roles, on the right-hand or ‘customer’ side, work on interactions going ‘outward’ from the platoon, typically putting into action whatever it is that the platoon needs to do to deliver its added-value to the overall story:

— Diplomat [EC: Customer-Relations] – ‘spies out the land’ and sets up outward connections with the world in the direction (literal or metaphoric) identified by the Navigator

— Grunt [EC: Customer-Channels] – takes outward-facing action along the connections set up by the Diplomat

— Shake-down [EC: Value-Return] – receives and verifies return from the outside-world, and distributes it through the platoon as guided by the Sergeant

(Note here that ‘customer’ may not be a good metaphor here – especially not if we try to make describe a nominal enemy as a ‘customer’ of military services! The actual relations with an enemy are closer to a clash between mutual anticlients – “someone in the same nominal shared-enterprise who fundamentally disagrees with how the Other is acting within that enterprise”.)

For a good fictional illustration of that set of subsidiary-roles and their relationships, see the 1963 film The Great Escape, a very much fictionalised version of the real mass-escape from Stalag Luft III POW camp in March 1944.

- ‘SBO’ Ramsey (James Donald) – Officer [guidance-services]

- ‘Scrounger’ Hendley (James Garner) – Fixer [Supplier-Relations] and Quartermaster [Supplier-Channels]

- ‘Big-X’ Bartlett (Richard Attenborough) – Navigator [Value-Proposition]

- ‘Tunnel-King’ Willie (John Leyton) – Diplomat/’Salesman’ [Customer-Relations] and ‘Grunt’ [Customer-Channels]

- ‘Forger’ Blythe (Donald Pleasance) – Backroom/Maker [Value-Creation]

- ‘Dispersal’ Ashley-Pitt (David McCallum) – Backroom/Maker [Value-Creation]

- ‘Surveyor’ Cavendish (Nigel Stock) – Backroom/Maker [Value-Creation]

- ‘Tunnel-King’ Danny (Charles Bronson) – Point-man/’Grunt’ [Customer-Channels]

- ‘Mole’ Ives (Angus Lennox) – Clean-up [Value-Outlay]

- ‘Intelligence’ MacDonald (Gordon Jackson) – Sergeant [Value-Governance]

- ‘Manufacturer’ Sedgwick (James Coburn) – Backroom/Maker [Value-Creation] and Shake-down [Value-Return]

Right near the start of the film, ‘SBO’ [Senior British Officer] Ramsey, in the archetypal ‘officer’ role, outlines the overall vision: “it is the sworn duty of every officer to attempt to escape, and the harass the enemy to greatest extent possible” – said to his counterpart, the camp-commandant von Luger. Several other times he reminds ‘Big-X’ Bartlett of possible big-picture consequences: “but have you thought of the human cost, Roger?”.

On the inbound or supplier-side – in effect, the interface with the ‘prison services’ providers, the guards – ‘Scrounger’ Hendley merges the archetypal roles of fixer (setting things up to receive goods and services) and quartermaster (receiving the goods and managing them), whilst ‘Mole’ Ives pays the all-too-final ‘price’ of that imprisonment.

In the centre, the pairing of ‘Big-X’ Bartlett and ‘Intelligence’ MacDonald connect the team to the big-picture vision and the practicalities respectively, whilst others such as ‘Forger’ Blythe, ‘Dispersal’ Ashley-Pitt and ‘Surveyor’ Cavendish do the background detail-work needed to make the whole action happen.

On the outbound or customer-side – in effect, the interface with the open world, or freedom – ‘Tunnel-King’ Danny does much of the literal ‘grunt’ of digging the tunnel, whilst the other ‘Tunnel-King’ Willie also provides emotional-support, the ‘diplomat’ or ‘salesman’ role, ‘selling’ the story of escape and freedom to Danny. ‘Manufacturer’ Sedgwick, shifting his archetypal maker’ role after the actual escape to ‘shake-down’, and thence receives the bounty from the escape, with all manner of lucky help, on the train, in the French cafe, and on the Spanish border.

(If you know the film, you might have noticed that I haven’t included ‘Cooler-King’ Hilts, played by Steve McQueen. In part that’s because, as an actor, he’s mainly there as a box-office draw, and almost nothing that he does occurred in the real-life story – for example, there were no Americans in the camp at that time anyway. But even more, to make him stand out in the film, in essence he careens from one archetypal-role to one another, without really settling in any one of them: in that sense, he’s more of a distraction, for this context here, than an illustration of anything useful.)

Note that the only ones to ‘receive’ the actual intended service of freedom – a ‘home-run’, a completed escape from German-controlled territory – are the three listed above on the ‘customer-side’ (characters Willie, Danny and Sedgwick in the film, two Dutch and a Norwegian in real-life). Most of the others, especially on the ‘supplier-side’, either failed or were killed (in the film and real-life too).

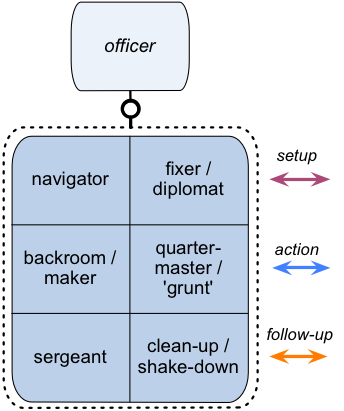

There’s also another variation of this overall analogy, in that for a smaller group – such as in some skirmishing-units, in a military context – we might reframe that set of roles into two trios, one ‘inward-facing’ (shown here on the left) and the other ‘outward-facing’ (shown on the right), but still the same split between what needs to happen before, during and after the main action:

In effect, it’s still the same roles, but the ‘outward-facing’ roles deal with all interactions with the ‘outside world’, rather than splitting between ‘inbound’ and ‘outbound’. We’ll particularly see that type of setup when the context is more of a bidirectional partnership with others, rather than a ‘through-flow’ of stuff coming in and stuff going out.

Leave a Reply