RBPEA: How to build a world beyond money

Beyond money.

It’s how most of us already run the economics of our own households.

It’s how most of us already run most of our day-to-day interactions at work.

It’s how perhaps most of us would already aim to interact with others in the wider world as well.

Indeed, it’s often only when we introduce into the picture a purported need for money that everything suddenly comes to a grinding halt. (No shortage of examples there: supermarket checkouts and train-station ticket-barriers are just two of all too many that come immediately to mind…)

Money makes the world go round? Hmm… – maybe more like money makes the world go stop…?

In the previous three posts, we’ve seen that to make sense of an enterprise, we need to to rethink it in terms of value, rather than money; we’ve seen that we can imagine a world beyond money; and we’ve seen some perhaps worrying reasons why we need to imagine a world beyond money.

So if the money-system is colossally expensive, absurdly inefficient and ineffective, is often more of a hindrance than a help, and we don’t even need it to exist in any case, why not get rid of it?

Yet having seen that there’s a real need there, how could we make it work, in real-world practice? Is it actually possible to build a world beyond money? Even from an architectural perspective, where could we start?

One clue comes from a key theme that we’ve seen in the previous posts – that we could replace each and every monetary transaction with just one question: “What do you need?”. That then gives us an anchor for the ‘Start Anywhere principle’ – hence, for example, we could start from anywhere within the shared-enterprise of the chocolate-biscuit, as in that first post in this series:

So start anywhere, from any element anywhere within that entire enterprise: from cocoa trees to biscuit-dough to chocolate-coating machines to metal-foil makers to delivery trucks to fuel for trucks to waste-collection, recycling, cafes, refrigeration, milk-cows, makers of grain-silos… Anywhere at all in that whole ecosystem: it really doesn’t matter where we start, because it’s an ecosystem in which everything ultimately depends on everything else.

(And because it’s an ecosystem within which everything ultimately depends on everything else, there is no place within that ecosystem that is ‘more important’ than anything else. It’s all one system: if we remove or ignore anything, without fully understanding what we’re doing and why, the system as a whole will fail – maybe not immediately, perhaps, but certainly over the longer-term. An important warning there…)

Start anywhere: don’t worry too much about where it is. We can move from there to any other element in the ecosystem, as soon as we’re ready to do so. The most important point is that we get started at all.

And for each element – person, machine, ingredient, process, whatever – we keep applying that one question: “What do you need?” What does that element need, in order to play its part in the overall ecosystem – in most cases not just once, but over and over again? How would each of those needs be satisfied, within the overall ecosystem? How could those needs be satisfied better, across the ecosystem as a whole? And how would we identify ‘better’, in what forms of value?

One tool that’s proven useful in tackling those questions is the ‘This‘ game – a set of checklists to help elicit the detail we need about elements in a context, and the relations between them:

Beginning from our ‘Start-Anywhere’ element as our initial ‘This’, we apply the checklists to each element – each ‘This‘ – to elicit whatever detail we need about that element and its relations with other elements in the overall ecosystem. Following those connections, we can move to another element, as our new ‘This‘ – and keep repeating the process, in whatever way we wish, until we have just enough detail for what we need to know about our current focus in the context.

One catch with the ‘This’ game is that is that, when using the full set of checklists, there’s a tendency to collect too much information. We can make the ‘game’ less intimidating by stripping the checklists down to a much simpler subset of just three questions, that we can then ask of each element:

- What is This? – tell us about what element is called, what it is, what it does, and suchlike

- What are the relations of This? – tell us about how and why this element connects with or is associated with other elements

- What are the changes of This? – tell us about how this element changes, or is changed, over time, by other elements, and so on

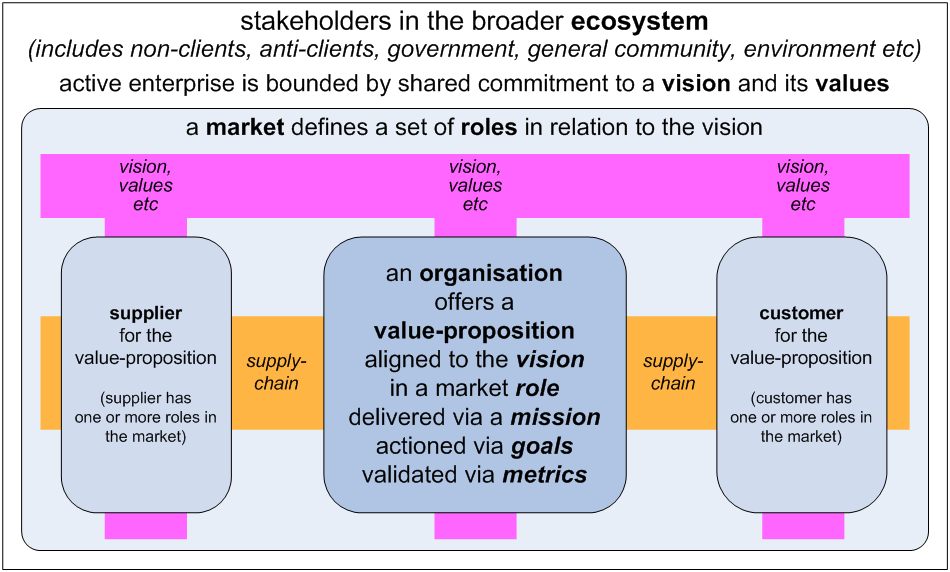

Another trap is that we can focus so much on the detail of structure that we may miss the story – the value and values that are our real concern here. To bypass that trap, remember that each interaction is a kind of ‘mini-enterprise’ in its own right. The content of the interaction, and the what each element does as its part in that interaction, is what we’d describe as the flow of value across that mini-enterprise – whereas shared-values are what hold the mini-enterprise together as a shared-enterprise. We can summarise that set of relationships visually as follows:

Linked to that, the Enterprise Canvas suite provides another set of visual-checklists to guide this kind of modelling of an enterprise. For this, we start with a simple assertion: that everything in the enterprise is or represents a service. If so, then we can describe anything in the enterprise always in the same way, as a kind of service and an associated set of service-relationships, which we can summarise visually as follows:

Again using the ‘Start-Anywhere principle’, we choose an initial element, and use the Enterprise Canvas toolset of methods and visual-checklists to help us elicit whatever information we need about that element. Then, as with the ‘This‘ game, we follow one of the associations there to take us to another related element, and repeat the same process there – on and on, to build up ‘just enough detail’ about the respective shared-enterprise and ecosystem.

For our purposes here, though, we need to remember to keep the focus on value and values – because those are the core factors underlying any answers to that question of ‘What do you need?’. In Enterprise Canvas, these come up particularly in two key parts of the toolset: the ‘validation services‘ that keep the service on-track to enterprise-values and enterprise purpose; and the section on ‘Investors and beneficiaries‘, that explore the connections and value-flows for what’s simplest to describe as ‘profit’.

To understand the latter, it’s essential to recognise that every organisation is ‘for-profit’‘ – it’s just that the meaning of ‘profit’ will itself vary according to the values in play. So yes, it’s common at present to describe ‘profit’ solely in monetary terms – yet our aim here is to make sense of a world beyond money, hence describing profit solely in monetary terms is exactly what we should not do here. Instead, for each element, we need to model the actual values in play, the actual forms of ‘profit’ that support the satisfaction (literally, ‘enough-making’) for each respective instance of that question of ‘What do you need?’

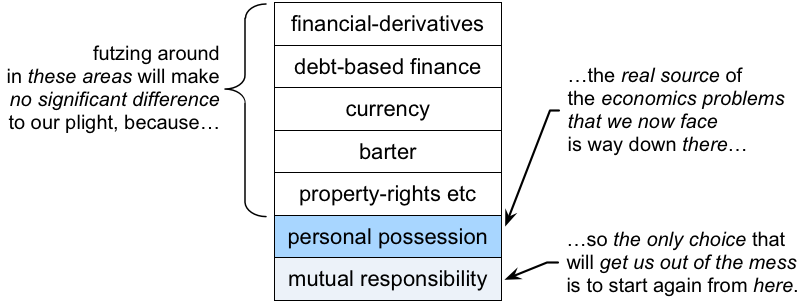

We also need to remember, however frustrating it may be in so many ways, the mess caused by the money-system is not actually our key concern here. In effect, the entire monetary-system is itself just an artefact or side-effect of trying to kludge together some sort of workable ‘fix’ for the system-level failures, yet without ever actually tackling the core root-cause itself. As we saw in the previous post, that root-cause – the real challenge, the real source for almost all of the problems we face at present, all the way out to a fully-global scale – is the concept of possession:

An ecosystem thrives through the flows of value into, out of, and throughout itself. Those flows take place via a mesh or network of mutual, interlocking responsibilities. Yet the moment any element attempts to possess some part of the value, the value-flow will come to a grinding halt – placing the entire ecosystem at risk. At present, though, we have a so-called ‘economic system’ whose core aim and action is that it would actively reward that kind of behaviour, and often actively penalise or punish any attempt to get the flows moving again. And we then wonder why things don’t seem to work too well, across the ecosystem as a whole? Hmm…

So yes, right now, we’re exploring the feasibility – the ‘How’ – for a world beyond money. Yet because the money-system is itself an artefact of that fundamentally-dysfunctional concept of possession, what we actually need for a world beyond money, is a world beyond possession.

(Beyond every form of possession. No exceptions. Which is why this can get real hard, real fast, for almost everyone. Yet if we don’t do so, on a seriously short timescale for this scale of change, we won’t survive. That’s the real challenge we all face right now…)

Building a world beyond possession might seem like an impossible task at present. But one way to get there is to at least work out how to build a world beyond money. So let’s do that, yes?

Leave a Reply